I. Introduction

Do States have an obligation to provide reparation to victims for harm caused as result of armed conflict? If so, under what conditions and through which mechanisms can victims demand that obligation? Recent advances in international law have made answering this question increasingly difficult, because different approaches have developed to determine the character of the obligation to provide reparation to victims of war. The emergence of international human rights law has resulted in the individual occupying an ambivalent position in international law, whereby individuals are recognised as rights holders but nevertheless not fully recognised as subjects. States have often proved not to be the only – and, in many cases, not the best – guarantors of the rights of their citizens. International law, however, recognises the rights of individuals and has established mechanisms for their direct exercise without the mediation of the individual’s State. However, those rights and mechanisms are governed by different legal frameworks of a universal and a regional nature, whose application also depends on how domestic legislation recognises those rights, making it difficult to determine the secondary obligations that derive from the breach of obligations under human rights law.

In answering these questions, this chapter will be divided into two main sections. The first (section II) will examine the obligation of States to provide reparation to victims of war by looking at the current status of international human rights law and international humanitarian law (IHL). The main thrust of this section will be an examination of the interplay between these two bodies of law, and of how to interpret them coherently to determine the degree of acceptance of and the conditions for exercising a right to reparation by victims of war. It is precisely the relationship between these two different legal sources of State obligations that has the potential to advance the right to reparation for victims of war.

The next section (section III) will analyse different mechanisms through which reparation has been provided to victims of armed conflict and will draw lessons from those experiences. Even though there is a wide array of mechanisms, including those established by human rights treaty bodies, international criminal courts, or domestic litigation, the focus here will be limited to those mechanisms that could include and guarantee access to large numbers of victims. This focus is important since armed conflicts usually result in heavy casualties and hence numerous victims. This section will investigate in concrete terms how to guarantee that all those who have suffered violations of their rights during armed conflicts can obtain reparation. This involves examining how two particular mechanisms established under the auspices of international law – the United Nations Compensation Commission (UNCC) and the Ethiopia–Eritrea Claims Commission (EECC) – have responded to the rights of victims (section III.A). The analysis will then turn to domestic mechanisms, including administrative reparation programmes for large numbers of victims of violations committed during internal armed conflicts – mechanisms that are often neglected by the literature on the responsibility of States under international law (section III.B). In most cases, these mechanisms are aimed at responding to violations of IHL and international human rights law. Thus they offer practical guidance for responding to violations of rights under both sources of law. Particular attention will be paid to arrangements made to guarantee the accessibility of a mechanism, to aspects of gender and the often-ignored position of women in armed conflict, and to the challenges of reconstruction and other State needs in its aftermath. A further consideration will be the importance of addressing personal harms – even more so than property losses.

The chapter will go on to draw from these examinations several lessons that can help us to identify the strengths and weaknesses of the different mechanisms (section III.C). In so doing, this chapter not only borrows from the rich analysis provided in the other chapters of this volume, but also tries to encourage a discussion that considers how the structure of these mechanisms could effectively respond to large-scale rights violations. These lessons are then the foundation of a series of proposals on how the right to reparation for victims of war crimes could be addressed (section IV). These proposals are intended to be realistic to ensure that promises are upheld and rights are translated into tangible results. By stressing the importance of a realistic approach, the recommendations try to practically address the consequences of serious violations for the lives of victims and thereby to recognise victims’ dignity.

II. The Possible Legal Foundations for an Individual Right to Reparation

There is much debate about whether or not States are obliged to provide reparation to victims and about the ability of victims to autonomously demand it. To some extent, this debate is the result of the ambiguous position of the individual in international law.Footnote 1 On the one hand, the individual’s human rights are recognised; on the other hand, the individual’s ability to make claims based on these rights still depends on the express consent of States, either by conventional acceptance or by customary acquiescence. It seems that public international law is still searching for a coherent position on the role of the individual following broad commitment in the UN Charter and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights to the promotion and respect of universal and equal rights of every individual, ‘both among the peoples of Member States themselves and among the peoples of territories under their jurisdiction’.Footnote 2 If IHL and international human rights law recognise the rights of persons, can those whose rights are violated make claims for reparation against the responsible State?

Much of this discussion has been informed by an analysis rooted in IHL: a body of law in which States are reluctant to accept individual rights. However, the right of victims of armed conflict to demand reparation from the responsible State cannot be defined without considering the obligations of States under international human rights law. For this reason, this section will start by examining the nature of the obligation under international human rights law to provide reparation to victims. Later, there will be examination of whether a similar obligation can be derived from IHL. This examination requires looking at how these two bodies of law interact and how this interaction can be interpreted coherently. Particular attention will be paid to what can be expected to remain an obligation under international human rights law even under the extraordinary circumstances of war. Moreover, it will be shown that the obligation to ensure an effective remedy persists.

A. The Right of Victims to Obtain Reparation under International Human Rights Law

Multilateral human rights treaties have recognised the right of victims of human rights violations to effective remedies. The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) establishes a general obligation (Art. 2(3)) to provide remedies to anyone whose rights and freedoms under the Covenant have been violated,Footnote 3 using similar language to Article 8 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. This obligation has been understood to be more than procedural and translates also into assuring ‘the enjoyment of rights recognized under the Covenant [by the respective] judiciary in many different ways, including direct applicability of the Covenant, application of comparable constitutional or other provisions of law, or the interpretative effect of the Covenant in the application of national law’.Footnote 4 The Covenant also guarantees ‘an enforceable right to compensation’ for victims of unlawful arrest or detention.Footnote 5 The International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD) goes even further, specifying ‘the right to seek … just and adequate reparation or satisfaction for any damage suffered as a result of such discrimination’.Footnote 6 The Convention against Torture also establishes the obligation to ‘ensure in its legal system that the victim of an act of torture obtains redress and has an enforceable right to fair and adequate compensation, including the means for as full rehabilitation as possible’.Footnote 7 More recently, the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons against Enforced Disappearances (ICPPED) established ‘the right to obtain reparation and prompt, fair and adequate compensation’,Footnote 8 and defined the forms reparation should take for particular types of violation.Footnote 9 These conventions, however, do not establish specific international mechanisms for complying with these obligations, but rather impose an obligation on each State to ‘ensure in its legal system that the victim … obtains redress and has an enforceable right to fair and adequate compensation’.Footnote 10 They rely on the State to guarantee the right to remedy. The Human Rights Committee has gone further by recognising that a general right to reparation for victims of violations of the rights established by the Covenant derives from the obligation to provide remedies:

Article 2, paragraph 3 requires that States Parties make reparation to individuals whose Covenant rights have been violated. Without reparation to individuals whose rights have been violated, the obligation to provide an effective remedy, which is central to the efficacy of article 2, paragraph 3, is not discharged. The Committee notes that, where appropriate, reparation can involve restitution, rehabilitation and measures of satisfaction, such as public apologies, public memorials, guarantees of non-repetition and changes in relevant laws and practices, as well as bringing to justice the perpetrators of human rights violations.Footnote 11

Regarding the obligation to provide an enforceable right to victims of torture under the Convention against Torture, the Committee against Torture (CAT) has explicitly stated that:

The obligations of States parties to provide redress under article 14 are two-fold: procedural and substantive. To satisfy their procedural obligations, States parties shall enact legislation and establish complaints mechanisms, investigation bodies and institutions, including independent judicial bodies, capable of determining the right to and awarding redress for a victim of torture and ill treatment, and ensure that such mechanisms and bodies are effective and accessible to all victims. At the substantive level, States parties shall ensure that victims of torture or ill treatment obtain full and effective redress and reparation, including compensation and the means for as full rehabilitation as possible.Footnote 12

Regional instruments for the protection of human rights also recognise the right of victims of violations of their provisions to effective remedies, using similar language to the United Nations’ conventions. Member States of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR)Footnote 13 and the American Convention on Human Rights (ACHR)Footnote 14 are obliged to provide effective remedies for victims of violations of the rights and liberties that they establish. The members of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR) recognise the right of ‘every individual to have his cause heard [comprising] the right to an appeal to competent national organs against acts of violating his fundamental rights as recognized and guaranteed by conventions, laws, regulations and customs in force’.Footnote 15

The European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) has affirmed that the obligation to provide effective remedies under Article 13 ECHR includes the existence of domestic mechanisms that can make reparation available to victims, in the form of compensation, at least for serious violations: ‘In the case of a breach of Articles 2 and 3 of the Convention, which rank as the most fundamental provisions of the Convention, compensation for the non-pecuniary damage flowing from the breach should, in principle, be available as part of the range of redress.’Footnote 16

Even if the Court admits that States have some discretion in complying with this obligation, it requires that ‘its exercise must not be unjustifiably hindered by the acts or omissions of the authorities of the respondent State’.Footnote 17 This obligation does not necessarily require investigating all allegations of failure to protect persons from the acts of non-State actors or third persons, but it is certainly applicable ‘for establishing any liability of States officials or bodies for acts or omissions involving the breach of their rights under the Convention’.Footnote 18 This is particularly true for breaches of Articles 2 and 3 ECHR, which protect the rights to life and personal integrity.

The Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACtHR) has also examined the domestic mechanisms used for investigating violations and for providing reparation in cases of human rights violations:

When assessing the effectiveness of the remedies filed under the domestic administrative jurisdiction, the Court must verify whether the decisions taken by the jurisdiction have made an effective contribution to end impunity, to ensure non-repetition of the harmful acts, and to guarantee the free and full exercise of the rights protected by the Convention. In particular, these decisions may be relevant in relation to the obligation to make integral reparation for any rights violated.Footnote 19

In this particular case, the IACtHR determined that Colombia breached the right to life and personal integrity of an opposition senator who was summarily executed, in a context in which the participation of military agents had been established in previous criminal and disciplinary investigations. Additionally, the Court assessed the process for determining State responsibility under administrative law, concluding that the failure to fully investigate the violations entailed a violation of the right to an effective remedy and judicial guarantees. In its judgment, the Court also considered that the reparation measures provided by the administrative procedure did not cover all of the violations committed and ordered supplementary forms of reparation.Footnote 20 In another case, the Court also examined the forms of reparation implemented not as a result of a court order but through a domestic reparation programme, assessing ‘whether the compensation awarded meets the criteria of being objective, reasonable and effective to make adequate reparation for the violations of rights recognized in the Convention that has been declared by this Court’.Footnote 21 The approaches followed by both the IACtHR and the ECtHR are discussed in detail by Clara Sandoval elsewhere in this volume.Footnote 22

In addition to examining the obligation of States to provide remedies and reparation for certain violations, these regional systems for the protection of human rights establish specific mechanisms for ordering reparation when it has been determined that a State has committed a breach of a primary rule. Article 41 ECHR, Article 63(1) ACHR and Article 27 of the Protocol to the African Charter on the Establishment of the African Court contain similar provisions, allowing the respective courts to order reparation (mostly in the form of compensation, except for the IACtHR, which developed a more comprehensive jurisprudence regarding the forms of reparation) if they have found there to have been a violation of the rights recognised by the Convention and if deemed necessary. When making these orders, the IACtHR has based its decision not only on Article 63(1) of the American Convention, but also on the recognition that States have an obligation to provide reparation for breaches of international law, citing the Factory at Chorzów caseFootnote 23 and other precedents. On these grounds, the Court has asserted that ‘every violation of an international obligation which results in harm creates a duty to make adequate reparation’.Footnote 24 The Court has developed a strong jurisprudence affirming this obligation and the right of victims of human rights violations to receive reparation.Footnote 25 In a more recent development, the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights has also declared that:

State Parties are required to ensure that victims of torture and other ill treatment are able in law and in practice to claim redress by providing victims with access to effective remedies. This includes the adoption of relevant legislation and the establishment of judicial, quasi-judicial, administrative, traditional and other processes. These processes should adhere to standards of due process and comply with the measures and protections envisaged under Article 1 of the African Charter.Footnote 26

This General Comment draws on both African and universal instruments to support the existence of such a right.Footnote 27

The International Law Commission (ILC) has implicitly affirmed the existence of an obligation that States provide reparation for human rights violations. When formulating the basic rules concerning the Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts, the ILC made no distinction between the existence of an obligation to provide reparation for harmful acts committed in breach of multilateral treaties – or treaties concerning human rights – and bilateral treaties. The notion of what constitutes a breach used by the ILC is broad, defined as ‘when an act of the State is not in conformity with what is required of it by that obligation, regardless of its origin or character’.Footnote 28

Another piece of evidence for the existence of an obligation to provide reparation to victims of violations of international human rights can be found in the provisions regarding who is entitled to demand reparation. The ILC distinguishes between the existence of an obligation to provide reparation and who may invoke this responsibility arising from a breach of the obligation.Footnote 29 Article 33(2), for example, left open the possibility of rights that ‘may accrue directly to any person or entity other than a State’.Footnote 30 The ILC even offers the example of human rights treaties that ‘provide a right to petition to a court or some other body for individuals affected’.Footnote 31

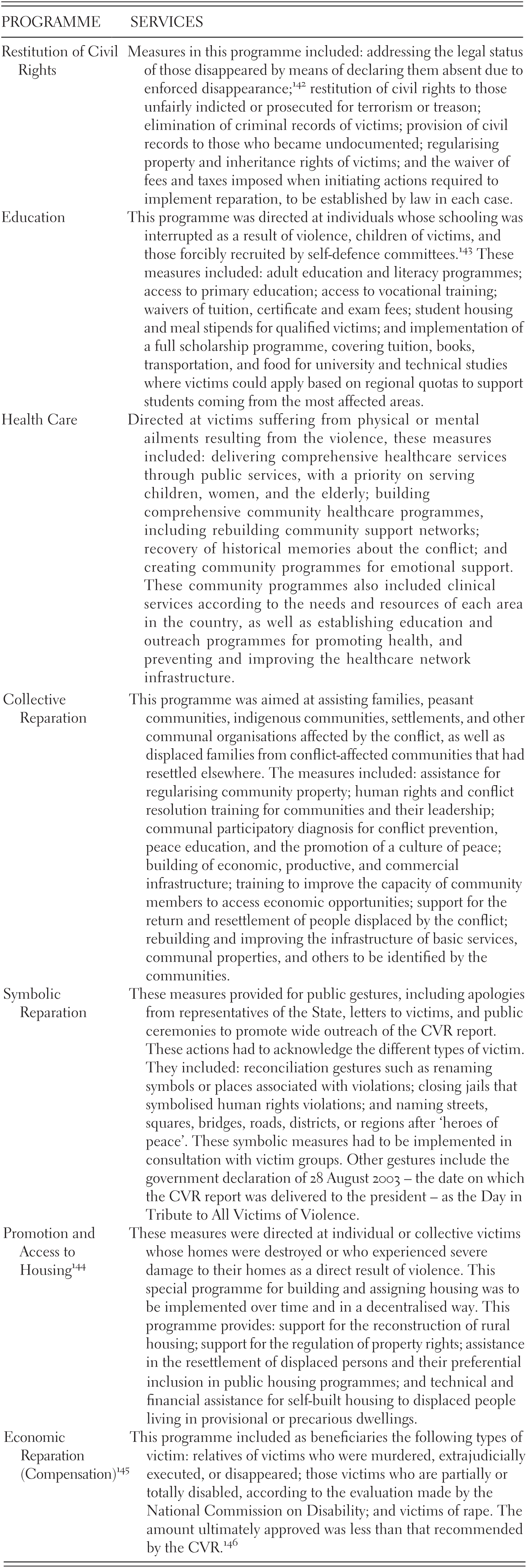

Some countries have addressed violations committed during internal armed conflict by means of administrative reparation policies.Footnote 32 These efforts have followed other experiences of providing reparation to victims of human rights violations within authoritarian or repressive regimes.Footnote 33 The norms that create these programmes are ambiguous with regard to the nature of the obligation they respond to; they use reparation terminology, but it is unclear how much they derive from an acknowledgement of State responsibility. The 2013 Peruvian Truth Commission report provides perhaps the clearest support for the idea that the reparation policy in that country derives from an acknowledgement of responsibility. When recommending establishment of the Comprehensive Reparations Plan, the Commission concluded that Peru was responsible for violations committed by all sides of the conflict. It reached this conclusion by analysing the conflict’s complex causes and not only the particular violations. It also considered the need to provide a common response to all victims as an imperative for inclusiveness and reconciliation.Footnote 34 The law that created the Comprehensive Reparations Plan explicitly stated that its purpose was to provide reparation ‘to victims of the violence that occurred during the May 1980 to November 2000 period, according to the conclusions and recommendations of the report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’.Footnote 35

Germany and Austria have also implemented several policies aiming to provide compensation to victims of different violations committed by the Nazi regime. Those policies affirm that they are not based on an acknowledgement of State responsibility; rather, they are voluntary gestures. However, there are some aspects to these policies that implicate them as a response to something more than a moral obligation. The preamble to the Law creating the Foundation Remembrance, Responsibility and Future recognises the severe injustices inflicted by the National Socialists on slave and prison labourers, and that German enterprises not only participated in those injustices but also bear a historic responsibility. The law also aims to settle legal claims against enterprises by recognising that ‘the German Bundestag presumes that this Law, the German–US intergovernmental agreement, the accompanying statements of the US government as well as the Joint Declaration by all parties to the negotiations provide adequate legal security for German enterprises and the Federal Republic of Germany’.Footnote 36 Assuming that the determinations of the Foundation have legal effect, it is possible to argue that this reparation policy derived from recognition of an obligation to provide such forms of compensation.

Domestic courts in ColombiaFootnote 37 and ChileFootnote 38 have also recognised the right of victims of human rights violations under conditions of internal armed conflict to reparation, based on human rights obligations and their respective domestic law. Dutch courts have come to a similar conclusion in cases of extraterritorial applicability of human rights obligations in the context of international armed conflict. In Nuhanović v. The Netherlands,Footnote 39 the Dutch Supreme Court found Holland responsible for failing to save the lives of people under the protection of its military battalion during a peacekeeping mission in Srebrenica. The Court based its decision on the failure of the State to comply with obligations under human rights law, citing the ECHR and the ICCPR, Bosnian domestic law and the ILC Draft Articles on the International Responsibility of States and Draft Articles on the Responsibility of International Organisations of 2011.Footnote 40 A more recent decision by the Appeals Court of The Hague has followed the same reasoning, carefully examining the conduct of the Dutch battalion to determine wrongdoing and confirming the obligation of the State to provide compensation (vergoeding).Footnote 41

It can be concluded that there are legal precedents under international human rights law to affirm that States have an obligation to provide reparation to victims of serious human rights violations, particularly in cases of summary executions, torture, and other violations of a similar nature. The conventional law mentioned, the instruments of soft law, the jurisprudence of regional human rights courts and the practice of several States all support the conclusion that such practice is commonly, if not universally, understood as deriving from a legal mandate. The obligation consists mostly in States having to establish mechanisms in their domestic systems through which victims can exercise their right to obtain reparation, provided that those domestic systems comply with the requirement of fairness, effectiveness, and independence to allow decisions to be adequate, effective, and prompt. The obligation to establish these mechanisms affirms that victims have a right to have access to mechanisms that allow them to claim reparation individually. Even if individual victims do not have general mechanisms under international law through which they can directly demand their right to reparation – except when especially provided, as is the case for Article 41 ECHR and Article 63 ACHR – they still have a right to reparation and a right to demand the existence and effectiveness of domestic mechanisms.

B. The Right of Victims to Obtain Reparation under International Humanitarian Law

Elsewhere in this volume, Shuichi Furuya provides a novel analysis of the existence of the right to reparation under international law.Footnote 42 His account of the evolution of this right need not be repeated here. At their inception, the 1949 Geneva Conventions recognised that States are liable for acts committed by their agents that constitute grave breaches of IHL. However, none of the provisions clearly established the right of individual victims to claim reparation. A 1952 International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) commentary on the Geneva Conventions expressly rejected that possibility, limiting that right only to States, based on the interpretation of the law at that time.Footnote 43 Article 91 of Additional Protocol I (AP I) to the Conventions contains an identical provision to that found in the IV Hague Convention. The text was not corrected to either narrow or expand its coverage, despite seventy years of changes in international law.

However, as Furuya notes, there has been significant change in the recognition of the rights of victims over the last thirty years, as expressed in non-conventional norms, especially those recognised in the Basic Principles and Guidelines on the Right to a Remedy and Reparation for Victims of Gross Violations of International Human Rights Law and Serious Violations of International Humanitarian Law approved by the UN General Assembly.Footnote 44 The Resolution establishing the Basic Principles was adopted after a long discussion and process of negotiation, and was informed by analysis of the existing jurisprudence and the state of international law with regards to the obligation of States to provide reparation to victims of gross violations of human rights and serious breaches of IHL.Footnote 45 The document recognises that included among victims’ rights to remedy for these types of violation are ‘[a]dequate, effective and prompt reparation for harm suffered’.Footnote 46

As is made clear by their name, the Basic Principles and Guidelines on the Right to a Remedy and Reparation recognise not only obligations towards victims of violations of international human rights law, but also serious violations of IHL. After listing several provisions of international conventions and documents that establish the right of victims to effective remedies, the preamble of the Basic Principles emphasises ‘that the Basic Principles and Guidelines contained herein do not entail new international or domestic legal obligations but identify mechanisms, modalities, procedures and methods for the implementation of existing legal obligations under international human rights law and international humanitarian law which are complementary though different as to their norms’. The sources of conventional law in support of the existence of a right to remedy and reparation for violations of human rights are manifold and clearly set out in the Basic Principles. The sources mentioned that affirm this obligation with regards to violations of IHL are more limited, making it more difficult to claim that the document does not entail new legal obligations, at least if considering conventional IHL on its own. In addition to the conventional sources mentioned above (Art. 3 of the 1907 Hague Convention and Art. 91 AP I), the Basic Principles refer to the obligations of individuals convicted by the International Criminal Court (ICC) and not to obligations of States.Footnote 47 However, it should be noted that, in the initial debates that led to the adoption of the Basic Principles, rapporteur Theo van Boven proposed an interpretation of gross violations of human rights and fundamental freedoms that included actions committed during international and non-international armed conflict. He also stated that, for the purposes of defining this topic:

Guidance may also be drawn from common article 3 of the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, containing minimum humanitarian standards which have to be respected ‘at any time and in any place whatsoever’ and which categorically prohibits the following acts: (a) violence to life and person, in particular murder of all kinds, mutilation, cruel treatment and torture; (b) taking of hostages; (c) outrages upon personal dignity, in particular humiliating and degrading treatment; (d) the passing of sentences and the carrying out of executions without previous judgment pronounced by a regularly constituted court, affording all the judicial guarantees which are recognized as indispensable by civilized peoples.Footnote 48

The special rapporteur also cited Article 75 AP I in support of this assertion, according to which civilian or military agents are prohibited at all times and places to carry out, inter alia, murder, torture of all kinds, or corporal punishment.Footnote 49 Moreover, during the debate and in the contributions from Member States, the inclusion of severe violations of IHL was not seriously objected to.Footnote 50 Indeed, one of the independent experts addressed this question, stating:

If the moral and conceptual point of departure for revising the guidelines on the right to reparation is the victim, then it follows that the guidelines should not exclude violations committed in the context of armed conflict. First, violations perpetrated during internal or international armed conflict may be at least as serious, if not more so, than those committed in peacetime. Second, international human rights law contains norms which permit no suspension, infringement or derogation, regardless of whether or not there exists a public emergency, even war. The right to reparation for violations of these non-derogable rights cannot be excluded from the revised guidelines. Moreover, as many of these non-derogable rights, such as the right not to be tortured, killed or enslaved, overlap with or are more clearly set out in norms of international humanitarian law, the expert considers it necessary to clarify the normative connection of the right to reparation to both international human rights law and international humanitarian law.Footnote 51

The International Law Association (ILA) provides additional support for the existence of the right of victims of armed conflict to demand reparation, distinguishing the existence of such a right (a secondary right) from the existence of concrete mechanisms to exercise it (what might be called a tertiary right).Footnote 52 The ILA argues that an obligation in a multilateral treaty can confer individual rights, giving victims of those violations a subjective right to reparation.Footnote 53

Other sources mentioned by the ILA are based on Articles 27 and 30 of Geneva Convention IVFootnote 54 and Articles 7 and 78 of Geneva Convention III,Footnote 55 which the ILA claims can be considered a source of rights conferred to individuals. Liesbeth Zegveld also argues that:

[T]he grave breaches provisions could be construed as conferring individual humanitarian rights against acts such as wilful killing, torture or inhuman treatment wilfully causing great suffering or serious injury to body and health. The same holds true for norms applicable in non-international armed conflicts, such as the prohibition of violence to life, outrages upon personal dignity, and humiliating and degrading treatment, stipulated in Article 3 common to the Geneva Conventions and in Article 4 of Additional Protocol II.Footnote 56

If protected persons were only indirect beneficiaries of IHL, the Conventions would not have used rights-inflected language when referring, for example, to the non-renunciation of rights by prisoners of war.Footnote 57

These precedents provide only mild recognition of the right of victims of war to obtain reparation. The ICRC study of customary IHL mentions several other cases of State practice. However, some of those references are opinions given in general by StatesFootnote 58 or pronouncements about obligations by other States.Footnote 59 Other instances of State practice being cited refer to reparation provided unilaterally by States absent clear opinio iuris, with some even expressing explicit reservations according to which those policies were held to be an acceptance of neither State responsibility nor an obligation to provide compensation for violations committed during World War II.

The ILA also lists precedents from national courts recognising the right of victims of armed conflict to reparation,Footnote 60 and even if these do not necessarily constitute a general acceptance of an individual right to reparation, they nonetheless demonstrate an increasing trend towards the understanding that it derives from a legal obligation.

In contrast, German courts have been reluctant to recognise the rights of victims of war to reparation. While consistently denying the claims of victims, however, some cases left room for accepting a contemporary right of victims of armed conflict to demand reparation. After some rulings left open the possibility of the existence of a right to reparation as lege ferenda,Footnote 61 more recent decisions have closed off that possibility. The German Federal Court of Justice (Bundesgerichtshof, or BGH) has affirmed:

There is still no general rule of international law under which an individual is entitled to compensation or damages for violations of international humanitarian law. Despite the constantly advancing developments at the level of human rights protection, which have led to the recognition of the individual as a partial subject of international law as well as to the establishment of treaty-based individual complaints procedures, a comparable development in the field of secondary rules cannot be demonstrated. Claims for damages arising out of acts contrary to international law against third-country nationals are, as a matter of principle, still due (‘zukommen’) only to the home State.Footnote 62

The Court asserted that the conclusion was based on ‘a still valid conception of international law as an inter-state law [where] indirect international protection is granted to the injured individual by virtue of diplomatic protection’.Footnote 63 The decision has, however, been criticised for having excluded from the reach of jurisdictional examination actions committed by German State officials during armed conflict by means of a restrictive and originalist interpretation of the German State liability regime.Footnote 64 This criticism also affirms that the decision contradicts the jurisprudence of the ECtHR regarding the scope of application of the ECHR (see section II.C).

Another argument for recognising a right to reparation for victims of armed conflict based on both human rights law and IHL lies in the establishment of principles and procedures relating to reparation before the ICC. The Court affirmed its acceptance ‘that the right to reparations is a well-established and basic human right, that is enshrined in universal and regional human rights treaties, and in other international instruments’,Footnote 65 citing the provisions of the universal and regional human rights instruments. This is of particular relevance for the recognition of the right of victims of severe violations of IHL, because the Rome Statute operationalises the provisions forbidding grave breaches of IHL as crimes. The immediate source for the reparation orders by the ICC is Article 75 of the Rome Statute, which allows the Court to ‘make an order directly against a convicted person’. This provision is not based on establishing State responsibility, yet it still affirms the existence of the right for victims. Moreover, the Court interpreted the obligation of States to provide ‘other forms of cooperation’, under Article 93, with regard to reparations limited to those set out at Article 93(1)(k), referring to ‘[t]he identification, tracing and freezing or seizure of proceeds, property and assets’.Footnote 66 The Assembly of States Parties had previously defined the scope of the jurisdiction of the Court in this regard as ‘exclusively based on the individual criminal responsibility of a convicted person, therefore under no circumstances shall States be ordered to utilize their properties and assets, including the assessed contributions of States Parties, for funding reparations awards, including in situations where an individual holds, or has held, any official position’.Footnote 67

This restriction is consistent with the regime established by the Rome Statute as a system of individual criminal responsibility. It is understandable that a criminal court dealing with the responsibility of individuals can neither assess State responsibility nor order States to provide reparation to victims. However, this does not mean that there is an absolute firewall between the judgments of the Court and the responsibility of States. A total separation is inconsistent with the types of crime covered, which in many cases require substantial control over resources and personnel that could allow establishing some level of responsibility of States. Moreover, it reflects the self-interest among States when defining international law in protecting themselves from liability, at the expense of the rights of victims of these crimes, even if the nature of the crimes might in many cases involve the responsibility of States. The findings of the Court can and should be used to establish State responsibility when the facts point towards substantial evidence that – in addition to the individual responsibility being determined by the Court – there could be State responsibility. This is not something to be ultimately decided by the Court, but in cases such as the investigation of crimes implicating a head of State whereby State resources were involved, it may be advisable for the Court to make a referral to another body to investigate and eventually establish State responsibility not only for the particular crimes investigated against the defendant, but also more generally on gross violations of international human rights law and IHL that could have been committed jointly with those crimes. This body could be the Human Rights Committee or the UN Security Council. Such referrals could help to provide a more comprehensive response to victims, not limiting reparation to the victims of the crimes of which the defendant is found guilty.

The system of liability established by the Rome Statute has other problems too. Since its reparation rulings can include victims of only the crimes of which the convicted person is found responsible, they leave many other victims without remedies. They can even render reparation decisions counterproductive, exacerbating intercommunity tensions and conflict. This is not a matter that the ICC can solve; it instead requires a coordinated effort with other mechanisms to establish the responsibility of States in relation to crimes found by the Court or violations committed in the wider context of those crimes and which could reach victims of violations beyond those of which the accused has been convicted.

The precedents analysed show that the existence of an individual right to reparation from States for victims of war is not itself fully supported by IHL. Article 3 of the IV Hague Convention and Article 91 AP I are not yet univocally understood as contemplating a secondary right for victims. Even if the violations of IHL can be considered to have infringed rights of individuals, most commentators and decisions do not recognise the existence of a right for those victims to directly claim reparation.

What provides additional ground to affirm the existence of an individual right to reparation of victims of armed conflict, though, is the increased support that the evolution of human rights law provides. Courts that have recognised the rights of victims of armed conflict to reparation have used that source to complement the provisions of IHL and interpret them systematically.

C. The Application of International Human Rights Law to Armed Conflict and the Right of Victims to Reparation

The close relationship between human rights law and IHL can be observed in the preamble to Additional Protocol II of the Geneva Conventions (AP II), applicable to non-international armed conflict, which ‘recall[s] that international instruments relating to human rights offer a basic protection to the human person’ and ‘emphasis[es] the need to ensure a better protection for the victims of those armed conflicts’.Footnote 68 This relationship, which is understandable in relation to human rights and its territorial applicability, also exists in the case of international armed conflict. Both fields have divergent origins and transformations, but up to only a certain point, because both stress the protection of human dignity and establish States’ obligations. The recognition of human rights as a centrepiece of international law in the UN Charter occurred in reaction to the crimes committed during World War II, which led to the pillars of the regulatory edifice of both systems: the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the 1949 Geneva Conventions, and the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.

Even if, at its origins, this effect was unclear, the development of international human rights law and the changing nature of armed conflict have eroded the traditional separation between the two fields that had been prevalent since the origins of the law of war. The complexity of this relationship has been examined in depth in a previous volume of the Trialogues by Helen Duffy, who asserts that:

[I]n recent decades there has been an overwhelming shift, such that the vast weight of international authority and opinion now confirms that [international human rights law] continues to apply in times of armed conflict. As such, the focus of the debate has shifted to how it co-applies alongside IHL … While, undoubtedly, some dispute on the relevance and applicability of human rights in armed conflict remains, … much of this reflects differing views on the pros and cons of how the law has developed, its historical or moral force, rather than on where the law stands today.Footnote 69

This is less of a question in cases of non-international armed conflicts, in which human rights law is applicable in the territory of the State. The issue is more complex, however, for extraterritorial situations, in which in general human rights law is not applicable. Nevertheless, there is substantial support to affirm that the international human rights obligations of a State govern its conduct beyond its territory under a number of exceptional circumstances. Over the last two decades, we have seen a general deepening of the acceptance that international human rights law is applicable to the conduct of a State when it exerts ‘effective control of the relevant territory and its inhabitants … exercis[ing] all or some of the public powers normally to be exercised by that government’,Footnote 70 excluding situations entailing aerial bombing. Developing this notion further, the ECtHR has affirmed that State responsibility derives from several factors, including ‘the strength of the State’s military presence in the area [and] the extent to which its military, economic and political support for the local subordinate administration provides it with influence and control over the region’.Footnote 71

This is consistent with the position adopted by the Human Rights Committee,Footnote 72 which used the concept of ‘effective control’ in cases of persons detained by Uruguayan agents in Argentina and Brazil.Footnote 73 More recently, the Human Rights Committee has expressed that:

[T]he Covenant applies with regard to all conduct by the State party’s authorities or agents adversely affecting the enjoyment of the rights enshrined in the Covenant by persons under its jurisdiction regardless of the location … [and the State should] acknowledge that the applicability of international humanitarian law during an armed conflict, as well as in a situation of occupation, does not preclude the application of the Covenant.Footnote 74

The International Court of Justice (ICJ) has supported this conclusion. In its Advisory Opinion on the Israeli Wall case,Footnote 75 the ICJ affirmed that violations of IHL give rise to an obligation of the State responsible for those breaches to provide reparation to those who suffered harm as a result. This served as the basis for the Court decision ordering reparation for violations of IHL and international human rights law in another international armed conflict: it decided that internationally wrongful acts committed by Uganda, including violations of IHL and international human rights law, which resulted in injury to the Democratic Republic of Congo and to persons in its territory gave rise to an obligation of Uganda to provide reparation for such violations.Footnote 76

How these two different bodies of law interact, however, is not easy to delineate. The context of war, in which some forms of large-scale violence and destruction are permitted, makes many provisions under human rights inapplicable. However, this does not mean that the human rights obligations of States are entirely irrelevant in situations of war. Helen Duffy affirms the need for co-applicability, ‘ensur[ing] that the human rights norms are not set aside to a greater extent than justified, consistent with the principle of IHRL [international human rights law] that permissible restrictions on rights should be no more than necessary’.Footnote 77 She exemplified this approach following the ECtHR’s reasoning in Hassan,Footnote 78 in which ‘each area of law informed the interpretation of the other – in interpreting the relevant rules of IHL, namely, the review by a competent body with “sufficient guarantees of impartiality and fair procedure”, the Court returned to Convention standards’.

The interplay between these two bodies of law can be summarised with reference to the affirmation made by Christopher Greenwood when commenting on the ICJ’s Nuclear Weapons advisory opinion: ‘Instead of the treaty provisions on the right to life adding anything to the laws of war, it is the laws of war, which may be of assistance in applying provisions on the right to life.’Footnote 79 Greenwood offers four situations in which international human rights are of importance to the conduct of war:

1. determining the rights of people who may not be covered by IHL, as in the case of the nationals of a belligerent party;

2. helping to interpret some provisions of IHL, for example in defining the requirements by which due process in the context of war complies with the essential requirements of impartiality and independence;

3. in cases involving the occupation of territory and the rights of its inhabitants; and

4. in the provision of a more effective enforcement machinery.Footnote 80

This poses an important question: to what extent does the factual description ‘armed conflict’ influence the right of victims to an effective remedy enshrined in Article 2(3) ICCPR?

Determining the extent of the right of victims of armed conflict to reparation requires assessing to what degree and under what conditions the right of victims to an effective remedy subsists or is affected by a situation of armed conflict. As the ILC Fragmentation Study concludes, ‘this requires [a] weighing of different considerations and not just deciding based on the expression of a preference. Then it must seek reference from what may be argued as the systemic objectives of the law, providing its interpretative basis and milieu.’Footnote 81

It can be concluded that the obligation of States to ensure in their own legal system that a victim of human rights violations can obtain redress and has an enforceable right to fair and adequate compensation is an obligation applicable, under the circumstances discussed, to armed conflict. This includes both the existence of a mechanism in the domestic system to guarantee that right and the effectiveness of said mechanism to provide prompt and effective remedies to victims, considering the context. In addition, there is strong support for affirming the existence of the obligation of States to provide reparation to victims of human rights violations even in the context of armed conflict with regards to rights that are non-derogable, or when conditions for the suspension of those rights are not met due to proportionality or discrimination. Objections to recognising secondary rights of victims of war, which are still a frequent practice among States and courts, have not addressed the applicability of human rights law to armed conflict or its interplay and concurrent application with IHL. Looking exclusively to IHL to establish whether this secondary right exists is an artificial limitation that contradicts the accepted interpretation of the scope of the obligations States have under human rights law. This limited interpretation results in a restriction on the rights of victims of armed conflict, because they would not be recognised as bearers of rights stemming from international human rights law.

III. The Practical Realisation of the Right to Reparation in Armed Conflict

There is little effect on recognising the existence of a right if the mechanisms available for the right bearer are non-existent, inaccessible, or compromised by a lack of independence from the respective government. In cases of war, which often involve large numbers of victims who live in war-torn societies, questions about the availability of effective mechanisms are even more important. Not only do such questions require examination of what the different legal regimes offer, but also they require examination of what, in concrete terms, they have delivered to them.

A comprehensive examination of all of the available mechanisms is beyond the scope of this chapter.Footnote 82 Those mechanisms include international human rights bodies that are part of the United Nations’ system of human rights protection, established by different treaties. They include the regional human rights mechanisms mentioned in section I, based on regional human rights conventions (the ECHR, ACHR, and APHRC). They also include international criminal courts, such as the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC), the Special Court for Sierra Leone (SCSL) and the ICC, as well as their respective mechanisms for ordering reparations or for helping victims to exercise their right to reparation through other tribunals. Among these mechanisms, the Trust Fund for Victims established by the Rome Statute offers a different approach, because it is not limited to victims of the particular crime. However, none of these international criminal courts has jurisdiction to establish the responsibility of the State.

Another possible route for realising the right to reparation relies on domestic courts. This includes, first, seeking reparation from courts belonging to the responsible State, which often involves obstacles in terms of the independence of courts, the application of the act of government or the political question doctrine; secondly, it involves seeking reparation through a third-party State – that is, neither the responsible State nor the State within which the violation was committed. When seeking State responsibility, this approach requires a party to overcome the obstacle of jurisdictional immunities.

Rather than discussing these different mechanisms in detail, the focus in this section will be on analysing those mechanisms that could be used in cases with large numbers of victims. Given the usually large-scale nature of armed conflicts, this approach aims to identify and assess how the right to reparation can be realised in practice for all victims of an armed conflict, as well as to respond to one frequent criticism – that is, the impracticability of a right of victims of war to reparation.Footnote 83 This focus is also apt to identify mechanisms suitable for reaching those victims who may have less information, connection, or resources to access justice and redress, particularly because courts or international bodies speak a language of law that is unfamiliar to many victims and are often located outside of the victims’ State of nationality. This requires an examination of the degree to which existing mechanisms for redress have been effective in providing reparation to the poor, the marginalised, and women, among the potential victims in a conflict. From that analysis, some lessons will be distilled that might provide guidance on what to prioritise and which choices to make when designing mechanisms in the future.

Furthermore, this section will concentrate on how massive reparation efforts can, first and foremost, respond to the rights of victims of personal harm. The intention is to stress the importance of responding to harms that cause severe suffering and affect the essential dignity of victims, particularly regarding the rights of life and personal integrity. This includes analysing one example of an internationally mandated reparation programme, the UNCC, and one example of reparation established by inter-State agreement, the EECC, both of which have dealt with personal harms. A further analysis then follows of several reparation programmes implemented to address the consequences of internal armed conflict, as well as in regard to post-authoritarian regimes, which have faced challenges that can offer lessons for addressing large-scale harm and personal loss resulting from armed conflict. The parallel between these two types of experience is not frequently explored when addressing reparation for victims of armed conflict and therefore may offer relevant insights.

Focusing in this way does not, however, mean dismissing the importance of the Trust Fund for Victims, the human rights mechanisms of the UN system, regional human rights commissions and courts, or the role of domestic courts. Each can be used effectively to respond to the rights of a particular victim or group of victims in the aftermath of a massacre or a particular military operation. They can also be used strategically, leading to broader class actions, or they can place political pressure on States to establish policies that could cover a whole category of victims, as was the case of the German Forced Labour Compensation Programme. Commissions of inquiry established by the Human Rights Committee have recommended broader reparation policies and political pressure deriving from the decisions of universal or regional human rights bodies can have similar effects.

A. Reparation under International or Inter-State Ad Hoc Mechanisms

Frequently, inter-State agreements after war are the result of extraordinary circumstances, which explains why there is no standard practice on defining them. After the atrocities perpetrated by its occupying forces, postwar Germany needed to come to terms with its neighbours and the international community to be accepted back into the community of nations. Establishing a common market in Western Europe and the need to ask for the protection of the United States and North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) during the Cold War made this need more pronounced.

Resolutions of the UN Security Council establishing reparation mechanisms are also extraordinary in nature. The need to guarantee conditions for the return of large numbers of Bosnian refugees who fled to other European countries after evictions and ethnic cleansing required restitution of their homes. This need helps to explain the creation of the Commission for Real Property Claims of Displaced Persons and Refugees in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Security Council Resolution 687, which created the UNCC, is also a product of extraordinary circumstances – that is, the near-universal denunciation of the 1990 Iraqi invasion of Kuwait, the uncontested influence of the United States in the Security Council during the years following the collapse of the Soviet Union and the possible seizure of Iraq’s oil exports. The apparent influence played by legal experts close to the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) and the UNCC during the negotiation of the Algiers Agreement between Eritrea and Ethiopia might explain the creation of the EECC in addition to the Boundaries Commission.Footnote 84 Among the key factors underlying the creation of these mechanisms are political considerations made by the Permanent Members of the Security Council. The Commission of Inquiry on Darfur submitted two requests to the Security Council. One aimed at referral of the situation to the ICC; the other aimed at establishment of a compensation commission:

… not as an alternative, but rather as a measure complementary to the referral to the ICC. States have the obligation to act not only against perpetrators but also on behalf of victims. While a Compensation Commission does not constitute a mechanism for ensuring that those responsible are held accountable, its establishment would be vital to redressing the rights of the victims of serious violations committed in Darfur.Footnote 85

However, Security Council Resolution 1593 responded only to the recommendation on referral to the ICC.Footnote 86 Victims’ right to reparation, abundantly justified by the Commission in this particular situation ‘on practical and moral grounds, as well as on legal grounds’,Footnote 87 was wholly ignored. As Christine Evans points out:

The indirect mention of the Trust Fund for Victims [encouraging States to contribute to it] is the only mention of the word ‘victims’, while the terms ‘compensation’ or ‘reparation’ do not figure at all in the resolution. Scholars’ and the public debate at the time mainly focused on the political dimensions of the referral to the ICC, while the recommendation regarding compensation was treated as a peripheral issue.Footnote 88

Even if extraordinary and ad hoc in nature, these examples offer interesting lessons that can be useful for defining reparations mechanisms for victims of armed conflict. For the purpose of this chapter, the most relevant cases are the UNCC and the EECC, because both examined claims involving personal harm caused by war, particularly killings and violations of physical integrity. Those limited to property rights, such as the Commission for Real Property Claims of Displaced Persons and Refugees in Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Housing and Property Claims Commission of Kosovo, or the Iran–United States Claims Tribunal, are interesting too, but they offer few insights into how to respond to personal harms.Footnote 89

1. The United Nations Compensation Commission

The UNCC had to address the daunting task of responding to large numbers of differing claims resulting from Iraq’s 1990 invasion of Kuwait. The UNCC’s mandate included harm resulting from violations of both the ius in bello and ius ad bellum,Footnote 90 even though the Commission largely addressed violations of the latter type. It received 2.6 million claims from ninety-six governments and it also allowed stateless persons to send their claims through non-State entities.Footnote 91 It awarded a total of 52.4 billion USD in compensation.Footnote 92 What is particularly relevant is that, despite the number and diversity of claims, the Commission assessed and granted awards that resulted in actual payments. Two conditions made this possible: (a) the particular nature of the Commission, which was responsible for distributing a fund that had a guaranteed source of income by means of a mechanism channelling a percentage of Iraqi oil sales to it; and (b) a departure from the traditional notion that States would represent the interests of the claimants.

The Commission did not receive claims directly, but through specially authorised governments and entities. However, the awards were granted individually and not in bulk to those States. The claimants were recognised as the subjects of their claims, even if a government played a significant role in collecting and sending their claims to the Commission, or in receiving the funds and making the direct payments to the victims through a process closely monitored by the Commission.Footnote 93

Another relevant feature of the Commission was how it prioritised claims related to personal losses over property and corporations’ claims for both processing and payment. This included: category A claims, involving individuals who had fled Kuwait after the invasion; category B claims, involving serious personal injuries, including the death of a direct relative; and category C claims, related to individual claims for losses of up to 100,000 USD. This latter category covered twenty-one types of loss, including losses occurred because of being forced to flee Kuwait as result of the invasion, other forms of personal injuries or anguish and property losses or a loss of income. Category D claims were similar to those of category C, but amounted to losses in excess of 100,000 USD. Category E claims addressed corporations and public-sector enterprises, and category F claims addressed governments and international organisations, including costs for evacuating citizens, government property damage, or environmental damage.Footnote 94

Claims under categories A, B, and C needed to derive directly from certain violations resulting from Iraq’s invasion and occupation of Kuwait. The first decision by the Governing Council of the Commission stated that claims under category A referred to people who left Kuwait between 2 August 1990 and 2 March 1991. Categories B and C included ‘death, personal injury or other direct loss to individuals as a result of Iraq’s unlawful invasion and occupation of Kuwait’.Footnote 95 Given that the majority of claims were about individual losses,Footnote 96 the Commission adopted different criteria for assessing each. An expeditious process granted 2,500 USD for those forced to leave the country, for serious personal injury, and for those whose spouse, child, or parent had died. The decisions were based on the provision of simple documentation regarding only the facts and dates, as well as the family relationship in those cases involving death;Footnote 97 detailed documentation about the material or immaterial damages was not required. Additional losses had to be claimed under category C (up to 100,000 USD) or under category D for larger amounts, which required additional evidence.Footnote 98 For assessing claims for harms under category C, ‘the Commission employed, in addition to individual review of claims where necessary, a variety of internationally recognized techniques for claims processing, including computerized matching of claims and verification information, sampling, and, for some loss elements in category “C”, statistical modelling’.Footnote 99 To guarantee the availability of funds, the Commission made an initial payment of 2,500 USD for all approved claims under categories A, B, and C, followed by full payment of all awards under category B. Subsequent payment phases completed the award of claims under categories A and C, including some meaningful payments for the remaining categories.Footnote 100

An overall examination of the compensation paid, however, shows that even if the majority of the recipients were individuals, most of the fund was used to pay claims under categories D, E, and F, which were also the most costly. Of the 47.9 billion USD paid, 13 million USD (less than 0.03 per cent) went to the 3,935 victims who suffered the death of a family member or who experienced serious personal injury under category B. More than 3 billion USD (less than 6.3 per cent) went to claimants under category A for losses resulting in having to leave Kuwait and more than 5 billion USD (less than 10.5 per cent) went to victims under category C.

Figure 2.1 compares the distribution of payments and claims awarded for each category. Some categories do not appear in the figure given their small relative size.Footnote 101

Figure 2.1 Distribution of Payments and Claims by the UNCC

On average, each claimant under category B received 3,400 USD. What remained went either to individuals or entities for harms that, in most cases, related to property losses, even if there were some claims under categories C and D that corresponded to loss of life or harms to personal integrity. It is illustrative to contrast the total amount for personal losses with that paid under category E1 (claims by corporations, private legal entities. or public-sector enterprises from the oil sector). Sixty-seven corporations received a total amount of 17 billion USD. It is true that losing property, savings, or expected earnings can be devastating for individuals and families. However, such losses cannot be compared easily to losing a loved one or to experiencing torture. The disparity between the amounts awarded for the loss of life or harms affecting personal integrity and for loss of property is not the result of the Commission having erred in its assessment of the claims received, but of the general structure of the programme, which derived from its extraordinary circumstances and the power dynamics that led to its creation. Because it was able to tap into unprecedented resources seized from Iraq by the UN Security Council, the programme covered all types of harm, from personal to property. If the availability of funds had been more limited, as is common in cases of international war or internal armed conflicts – that is, in cases in which the wealth of the defeated party cannot be partially seized for funding reparation – the distribution of awards and even the structuring of categories defining the parameters for claimable losses would necessarily have been limited.

2. The Eritrea–Ethiopia Claims Commission

The EECC offers important lessons in two different aspects: the definition of violations of ius in bello that gave rise to liability; and the definition of compensation amounts for those violations that were established. However, despite these contributions, there are aspects of the Commission’s work and framework that make it a dangerous precedent for addressing harms caused to victims of armed conflict. The results of the EECC show how inadequate it is to continue relying on inter-State arbitration procedures if the goal is to respond to harms suffered by victims of war.

The EECC assessed the claims presented by both States for loss, damage, or injury relating to the conflict and resulting from violations of IHL. The assessment made of each claim serves as useful guidance for evaluating under which conditions harms committed during an international armed conflict can lead to State liability, including the determination of how to define the degree of responsibility of the corresponding State for the harms caused. These are relevant contributions for the development of the case law on grave breaches of IHL and the obligation to provide reparation to victims. Particularly relevant are the standards used for assessing claims for indiscriminate shelling and aerial bombardment against civilian targets, taking into account the specific context and the role played by both parties in preventing civilian casualties.Footnote 102 The allocation of ‘the percentage of the loss, damage or injury concerned for which [the Commission] believes the Respondent is legally responsible, based upon [the Commission’s] best assessment of the evidence presented by both Parties’ is also useful for establishing criteria when there are multiple causes operating at the time.Footnote 103 The work of the Commission also offers useful guidance for the examination of allegations of rape and sexual violence. It stressed that IHL protects persons subjected to rape and sexual violence, emphasising that rape ‘is an illegal act that need not be frequent to support State responsibility’; the Commission ‘look[ed] for clear and convincing evidence of several rapes in specific geographic areas under specific circumstances’.Footnote 104 It is also relevant that the Commission affirmed the obligation of the parties to ‘impose effective measures, as required by international humanitarian law, to prevent rape of civilian women’, especially in areas where large number of troops were in close proximity to civilian populations for long periods of time, which was thought to generate the greatest risk of opportunistic sexual violence by troops.Footnote 105 Finally, the Commission made several distinctions regarding displaced persons and liability for violations of IHL, particularly between persons displaced as a result of fear, which the Commission called ‘indirect displacement’, and displacement resulting from orders or forceful actions – that is, ‘direct displacement’.Footnote 106

The Commission also developed an interesting notion for defining the compensation awards, considering the limited evidence of the harms. The Commission considered that the lack of evidence due to the nature and extent of the case demanded a trade-off. This notion was based on experiences of other bodies, such as the UNCC, where adopting less rigorous standards of proof resulted in reduced compensation levels. As the EECC explained, it ‘took into account a trade-off fundamental to recent international efforts to address injuries affecting a large number of victims. Compensation levels were thus reduced, balancing the uncertainties flowing from the lower standard of proof.’Footnote 107

The Commission used the notion of proximate cause to define causation. The criterion considered the foreseeability of the consequences resulting from the actor’s violation as an element that ‘provides some discipline and predictability in assessing proximity’.Footnote 108 However, foreseeability was used as a consideration and thus not a determinant factor. Other factors for determining the awards were:

… the nature, seriousness and extent of particular unlawful acts. It has examined whether such acts were intentional, and whether there may have been any relevant mitigating or extenuating circumstances. It has sought to determine, insofar as possible, the numbers of persons who were victims of particular violations, and the implications of these victims’ injuries for their future lives.Footnote 109

The EECC also made a distinction between the standard of evidence to establish that damage at all occurred:

[F]or purposes of quantification, it has required less rigorous proof. The considerations dictating the ‘clear and convincing standard’ are much less compelling for the less politically and emotively charged matters involved in assessing the monetary extent of injury … Requiring proof of quantification of damage by clear and convincing evidence would often – perhaps almost always – preclude any recovery. This would frustrate the Commission’s agreed mandate to address ‘the socio-economic impact of the crisis on the civilian population’ under Article 5(1) of the Agreement.Footnote 110

However, other criteria used by the Commission require more careful scrutiny and even robust criticism. One is the decision to determine liability not for each individual incident, but for ‘serious violations of the law by the Parties, which are usually illegal acts or omissions that were frequent or pervasive and consequently affected significant numbers of victims’.Footnote 111 This standard for defining State liability resulted in the rejection of several claims not because the Commission found that they did not pertain to serious violations of IHL, but because they did not respond to a demonstrated pattern of abuse, were not widespread enough or were not of a pervasive nature. Violations such as summary executions, even if sufficiently established by the Commission, did not result in the ordering of awards in favour of the victims. Moreover, most of the claims accepted regarding ius in bello referred to looting and the destruction of property, because they complied with the requirement of being widespread. In three situations, the Commission did not apply this requirement, apparently because it considered the violations pervasive enough, even if insufficiently frequent, to form a pattern – namely, on assessing rape,Footnote 112 on the forceful displacement of the residents of a village,Footnote 113 and on the destruction of a monument of incalculable cultural value.Footnote 114

Requiring some violations to be frequent and excluding summary executions from the notion of pervasiveness is a serious pitfall. The lack of a clear justification for this choice only compounds the problem. It is understandable that a cut-off criterion might be defined based on severity, but severity should refer to the nature of the violations suffered by victims entitled to reparation and not to the nature of the responsible State’s wrongdoing, which the EECC assumed was demonstrated by the frequency and widespread nature of the violations. Defining a mechanism for assessing the rights of victims of war in contexts of large-scale violations does not imply adding a requirement for those violations to be systematic or widespread. As Emanuele Sommario rightly concludes, by limiting reciprocal claims to widespread and systematic violations, the parties absolved themselves of the liability they incurred in respect of grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions, because they imposed a restriction on victims who might otherwise pursue reparation through other means.Footnote 115

The Final Award decision reveals too the shortfalls involved in relying on States to submit claims on behalf of their nationals. The Commission, facing time and resource constraints, opted ‘not to utilise mass claims procedures envisioned as a possible option’,Footnote 116 but to proceed in the same way as the UNCC: by receiving the claims of individuals only through their respective States or other bodies. However, a solution that was adequate in the context of the nature of the claims and the capacity of the States in the UNCC case was not appropriate to a conflict of this nature. The EECC had to overcome considerable obstacles in examining forms submitted by Eritrea that were incomplete, did not respond to the findings of liability by the Commission or lacked supporting evidence, highlighting the risk of relying on States with different capacities to conduct adequate outreach and registration.

The EECC held that ‘[t]he claims before the Commission are the claims of the Parties, not the claims of individual victims’.Footnote 117 It considered that it could assess only the damages of the claimant State, because fixed-sum damages to be distributed to the individual ‘would not reflect the proper compensation of that individual’.Footnote 118 In the Commission’s reasoning, since it was impossible to assess the conditions of detention for each prisoner of war, compensation amounts would not respond proportionally to the harm suffered; it was better to determine damages globally for each State, leaving to the States the task of distributing any award among the direct victims. The Commission encouraged the parties to compensate each victim appropriately, but limited its role to ‘calculat[ing] the damages owed by one Party to the other’.Footnote 119 With regard to the awards for victims of rape, ‘the Commission express[ed] the hope that Eritrea (and Ethiopia) will use the funds awarded to develop and support health programmes for women and girls in the affected areas’,Footnote 120 but it could not guarantee that either party would do so.

A possible explanation for these limitations on the work of the Commission was the one-year time frame imposed by the Algiers Agreement in which to receive claims, and the need to simplify and expedite the process. However, if there had been an interest by any of the Parties or pressure from the Commission itself, there was no reason why the deadline could not have been moved to allow implementation of a mass claims process.Footnote 121 These constraints do not fully justify the Commission’s shortfalls. The self-imposed mindset among the legal experts of the Commission, limiting matters to an inter-State process, provides the more relevant lesson on how a huge effort can result in little more than declaratory decisions.

The outcome of this extensive work was a process whereby the governments of Eritrea and Ethiopia competed between themselves on the question of which State could demonstrate that it had suffered more violations of IHL, so as to determine which of them suffered more harm as result of those violations. Tabling a debate about the existence of a violation of ius ad bellum did not help matters; rather, it increased the stakes for the competition of claims. The Commission examined each claim carefully and tried to subject each to rigorous legal reasoning, but it entirely failed to respond to the expectations and needs of victims, because it relied on the State-centred, lump-sum settlement approach that had been prevalent before 1990, but that which, as Furuya explains elsewhere in this volume,Footnote 122 has been superseded by a growing social consciousness of the right of individual victims to reparation. By expecting States to truly represent the interests of victims, the Commission failed in what was its most important task.Footnote 123

B. Reparation through State Administrative Processes

On occasion, States have unilaterally instituted policies for providing reparation or assistance to victims of armed conflict. These policies are in line with the call in the UN Basic Principles for the establishment of ‘procedures to allow groups of victims to present claims for reparation and receive reparation, as appropriate’,Footnote 124 without depending on court decisions. Some even provided important precedents that led to the development of the UN Basic Principles. However, they are frequently omitted from studies about reparation under international law.