In 1626, workers took aim at four spots marked on the floor of the largest church in Christendom, Saint Peter’s Basilica in Rome. The structure’s immense dome hovered more than four hundred feet above them, for they stood at the intersection of the church’s nave and transept. They began to dig. These shafts, when eventually filled with masonry, would support a towering bronze tent (called a baldacchino) over the high altar. As shovels and picks hacked deep, the excavation took laborers back through layers of history. After breaking through the floor of the Renaissance church, they burrowed through the fill separating it from its fourth-century predecessor. They then cracked through that building’s pavement and struck an ancient cemetery (Fig. I.1). If authorities expected to find anyone’s remains, they were those of Peter himself or one of his papal successors, for they believed the key apostle and later popes were buried here.

Figure I.1 Successive layers of history are visible in this cross section of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. The Renaissance church stands atop a crypt, where its predecessor, “Old St. Peter’s,” was itself built atop a Roman cemetery (also in plan below). The high altars of both churches were positioned above what was believed to be the tomb of St. Peter (P). Flavius Agricola’s funerary monument was discovered a mere four meters away in Tomb S when Baroque-era workers were digging foundations for the southeastern column of the towering baldacchino.

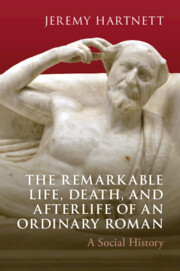

Instead, at the bottom of the southeastern shaft, the tomb and funerary monument of a man named Flavius Agricola came to light. In his marble sculpture, he was portrayed reclining at table, and the inscription below this depiction embraced the polar opposite of Christian morality and beliefs. It encouraged readers to enjoy corporeal pleasures, especially wine and lovemaking, since “after death earth and fire consume all else.” Red-faced papal authorities destroyed the inscription, though not before antiquarians clandestinely recorded its contents. The sculpture, after passing through the hands and before the eyes of families and institutions with global reach, has been exhibited in the Indianapolis Museum of Art since 1972.

Flavius’ funerary ensemble, even as it offered an embarrassment for Vatican authorities, reveals the fascinating biography, family, worldview, and choices of a man whose lineage was only a couple generations – if that – removed from slavery. This book delves, as deeply as the evidence will allow, into the details of Flavius’ life, his commemoration in death, and his sculpture’s many subsequent travels. The picture afforded by Flavius’ portrait, epitaph, tomb, and cemetery not only permits us to explore the lived experience of this particular Roman but also sheds light on how captivating realms of Roman life – sex, religion, philosophy, dining, notions of the body, low-brow fluency in high culture, and more – were experienced by many excluded from Rome’s halls of power.

This Roman Life

If asked to imagine “a Roman,” most people would likely flash to a big-ticket name like Julius Caesar, Livia, or Constantine. After all, they are famous for a reason – their lives were extraordinary, their impact and legacy immense. Even among Roman powerbrokers, they were atypical. And when we place them within the broader contexts of the senatorial class, the population of Rome, or of the whole of the Roman Empire, the peculiarities of their lives stand out in still-higher relief. And yet, in documentaries, books, and even plenty of Roman history classrooms, Caesars, Livias, and Constantines dominate our attention.

This book focuses on “a Roman” of a markedly different type. Flavius Agricola existed far below Rome’s innermost circles. In the grand scheme, Flavius’ life was not nearly as impactful as these others. But his experience is certainly more representative of the way more Romans lived: not peering out from the palace but gazing up at it. That perspective alone offers one reason to dedicate the following pages to this individual, his life, his family, and, ultimately, the travels of his monument between Rome and Indianapolis. Why else?

I want to offer several additional and intertwined responses to this question. Recent decades have pushed back against “great man” history, which focuses on prominent individuals (predominantly men) and brings the accompanying assumption that these individuals were the foremost agents in shaping the course of history. Instead, scholars of ancient Rome and other periods have trained their attention on broader swaths of the population. Coordinately, focus has expanded from military matters and politics to any number of different realms: family, leisure, medicine, commerce, freedom and enslavement, gender, and others. Scholars usually lump together these topics under the banner of “social history.” Flavius definitely took his place amid this broader mass of Romans, and his funeral ensemble explicitly draws our attention to spots beyond the battlefield and senate house.

One particular challenge of looking beyond the halls of power is keeping track of individual experiences. Let me illustrate this through a familiar lens. Just about everyone recognizes the Flavian Amphitheater, even if they call it by its medieval moniker of the Colosseum, and many understand that the vast majority of the texts that come down to us were written by and about the senators and other elites who sat in the amphitheater’s first few rows, since seating was organized by legal rank. (It was not the case that middle-class folks could save their bucks and buy arena-side seats.) Those are the faces we are usually able to see, whose details we can make out. When we want to look beyond the front rows, our vision become hazier, since the further one ascends the less we have written by, or surviving from, individuals. As a result, one approach has been to study these ranks of society in the aggregate by, for instance, statistical analysis of their funerary inscriptions, plotting the sizes and locations of houses of different scales, or, to take an example from my own scholarship, examination of the streetside benches on which they perched when they needed a rest from a city’s bustle. While these approaches can trace general contours of an issue, they also end up feeling like coins showing Colosseum crowds from on-high (Fig. I.2). We see lots of heads, but the only face we encounter is that of the emperor on the other side.

Zooming in on Flavius, then, allows one story to unfold. Flavius and his life are not meant to be stand-ins for all Romans and all stories, but only what they are – a case study as closely examined as the evidence will allow and reasonable reconstruction may permit. In fact, that they are not stand-ins is part of the point. There can be a tendency, when questions are asked about Roman daily life, to respond with something akin to, “This is what Romans did” or “This is what Romans believed.” The truth, of course, is more complicated, as all individuals had their own experience and worldview, depending on their legal status (free, freed, and enslaved), their gender, race, and place of origin, to name a few of many distinguishing features. This is Flavius’ story, his family’s story, and no one else’s. The following pages aim to explore a few of his experiences and beliefs, and, to the degree possible, to situate them within a broader context.

Part of the point of examining Flavius’ life is to walk all the way around it. So many treatments of the Roman experience splinter everyday life into categories: work, religion, sex, entertainment, politics, and the like. This is understandable, for grouping sources by topic makes logical sense. And yet we know intuitively that reality does not cleave cleanly in this way but that life’s inevitable messiness tends to weave many realms together in richly textured and complicated patterns. In the pages that follow, I will treat topics serially for the sake of organization, but not with any expectation that, if we find the right key, everything will click into place unproblematically. Rather, sniffing out the tensions and contending with them is part of the point.

And then there is Flavius’ story. Most treatments of Rome’s lower classes take the shape of a funnel: they start with some broad topic at the top and then trickle down to the best illustrations of the issue at hand. By contrast, this book is more pyramidal, starting with the specific point of Flavius’ life and then expanding outward as we encounter and wrestle with the various features of that life and its legacy. The result, I hope, is a narrative that illustrates one way “to do social history,” with the reader as a partner in the intellectual inquiry.

Outline

The pages that follow are divided into two parts – one discussing Flavius’ ancient existence and one tracing the sculpture’s travels from Rome to Indianapolis.

The opening chapter of Part I introduces the various pieces of Flavius’ funerary ensemble, positions them within the Vatican necropolis, and contends that they combined to form a cohesive, carefully conceived whole. Who was Flavius Agricola and what did he want people who saw his funerary ensemble to know about him? Chapter 2 guides readers through his self-presentation, discussing the ways his epitaph borrowed phrases from famous poems, the surprising potency of at-home dining, and the thin line separating mortals from the divine in the Roman world. Of the fifteen lines in Flavius’ epitaph, seven offer a subbiography of the deceased’s wife of thirty years, Flavia Primitiva. The next two chapters consider her portrayal. As we shall see, Flavia is described both through stock terms for Roman women and also as an adherent of the cult of Isis. Chapter 3 weighs this tension before Chapter 4 imagines Flavia’s experience within Rome’s principal sanctuary of Isis. Such worship brought certain outlooks that contrast with what Flavius espouses in his monument. These different worldviews and the challenges of reconciling them occupy Chapter 5, while Chapter 6 shifts focus from Flavius’ life to the experiences of those visiting his tomb after his death, particularly as they raised a glass alongside Flavius’ sculpture.

Papal panic after the discovery of Flavius’ monument and the obliteration of his epitaph were only the first of many different responses, manipulations, and reframings that Flavius’ monument underwent between its discovery in 1626 and its current exhibition at the Indianapolis Museum of Art. Part II offers what has been called an “object biography” of Flavius’ sculpture as it has moved through contexts as diverse as Baroque palazzi in Rome, the Parisian workshop of an infamous art dealer, Manhattan galleries and auction houses, and the pages of the New York Times. Through these different settings, the artwork passed before the eyes of cardinals, royalty, leading artists of early twentieth-century France, mustache-twisting American industrialists, and bargain-hunters on the lookout for the perfect finishing touch for their Hamptons estate. These travels and audiences do not just offer colorful stories but document the malleability of the past in the hands of the present. Flavius has had many garments of meaning draped across his chiseled abs, from totem of paganism and emblem of ancient majesty to focal point of national identity and symbol of classy classicism. Chapter 7 and Chapter 8 follow those threads and invite us to entertain the complex ways that our current perception of artworks is shaped by, and entangled in, those past understandings.