Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Acknowledgements

- Contents

- List of Tables

- Note on Transliteration

- Note on Sources and Conventions

- Introduction: A Portrait of the Artist

- 1 In God’s Image

- 2 The ‘Great Thing’ and the ‘Small Thing’: Mishneh Torah as Microcosm

- 3 Emanation

- 4 Return

- 5 From Theory to History, via Midrash: A Commentary on ‘Laws of the Foundations of the Torah’, 6: 9 and 7: 3

- 6 Conclusion: Mishneh Torah as Parable

- Appendix I The Books and Sections of Mishneh Torah

- Appendix II The Philosophical Background

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index of Citations

- Index of Subjects

2 - The ‘Great Thing’ and the ‘Small Thing’: Mishneh Torah as Microcosm

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Acknowledgements

- Contents

- List of Tables

- Note on Transliteration

- Note on Sources and Conventions

- Introduction: A Portrait of the Artist

- 1 In God’s Image

- 2 The ‘Great Thing’ and the ‘Small Thing’: Mishneh Torah as Microcosm

- 3 Emanation

- 4 Return

- 5 From Theory to History, via Midrash: A Commentary on ‘Laws of the Foundations of the Torah’, 6: 9 and 7: 3

- 6 Conclusion: Mishneh Torah as Parable

- Appendix I The Books and Sections of Mishneh Torah

- Appendix II The Philosophical Background

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index of Citations

- Index of Subjects

Summary

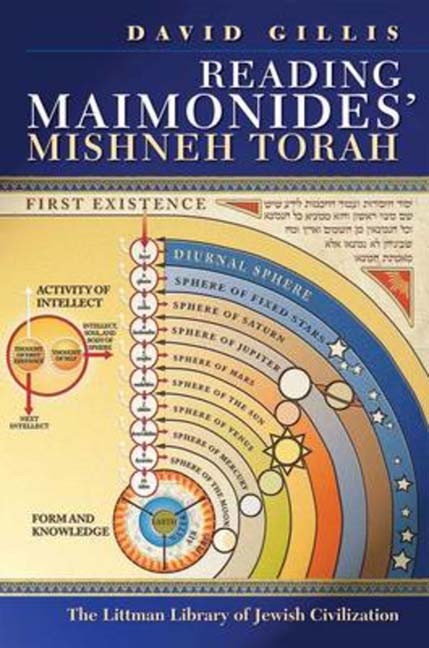

IT WAS ASSERTED in the Introduction that Maimonides based the design of Mishneh torah on the cosmology set out in ‘Laws of the Foundations of the Torah’. To recapitulate, Mishneh torah comprises ten books on man–God commandments and four on man–man commandments. In the Maimonidean universe ten is the number of the orders of non-corporeal beings consisting of form only, the separate intellects, better known as angels, while four is the number of the elements of matter: fire, air, water, and earth. Ten is also the number of the nine spheres plus the lowest of the separate intellects, the agent intellect. The books on the man–God commandments correspond to the angels and spheres, while those on the man–man commandments correspond to the elements. This microcosmic form represents the ‘great thing’, physics and metaphysics, cradling the ‘small thing’, the practicalities of halakhah.

Here and in the following two chapters, this idea will be substantiated more fully. The aim will be to demonstrate in detail that Mishneh torah is shaped by the synthesis of Aristotelian and Neoplatonic physics and metaphysics that Maimonides inherited from the Islamic philosophers, chiefly Alfarabi and Avicenna. In conjunction with the idea of man as microcosm, with which we are already supplied, I will ponder what this means for the place of the commandments in Maimonides’ scheme of things. The general idea, though, is the one broached in the Introduction: if, as argued in the previous chapter, a virtuous person aligns his or her personality with the perfect order of the cosmos, then the function of the commandments, the microcosmic design implies, is to bring about such an alignment.

Of course, Mishneh torah is not directed only at the individual. The welfare of the body also ‘consists in the governance of the city and the well-being of the states of all its people according to their capacity’. So while intellectual and moral virtue are the subjects of ‘Laws of the Foundations of the Torah’ and ‘Laws of Ethical Qualities’, the product of the comprehensive legislation in Mishneh torah as a whole is political virtue, that is, the ideal state, as conceived at the end of ‘Laws of Kings and Their Wars’. The ideal state, no less than the ideal individual, is a microcosm.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Reading Maimonides' Mishneh Torah , pp. 156 - 207Publisher: Liverpool University PressPrint publication year: 2015