Thinking Europe ‒ No Future?: A Continent Torn Between Two Dreams

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 07 January 2021

Summary

Europe is a continent without a future. Not because of the structural fault lines and increasing dysfunctionality of the EU ‒ the crisis of its currency, the influx of refugees or the threat of a European break-up ‒ it has no future because its societies and leaders have chosen not to have one. Future means change, and change, we have learned, is mostly negative: climate change, collapsing social systems, threats to social cohesion, the likely loss of Europe's global position, the problems of demography, and the limits of growth. European societies have therefore decided not to have a future, but to drag out the present as long as possible. Our civilisatory goal appears to be to retreat into an oasis of wellness and conspicuous consumption.

We have to accept a considerable degree of cognitive dissonance to maintain this blessed state. We are the first generation in history to have a good idea of what the consequences of our actions will be. Scientific models and analyses have been applied to crucial scenarios, most significantly linked to global warming, the rise of global populations and the decline of European ones, to the automatisation of work, the consequences of unsustainable consumption, and the extremes of reckless capitalism, and while there is a range of interpretations, the general direction of the developments affecting our future is clear. It is also transparent that our room for action is narrowing with every passing day, but instead of imagining and constructing the societies we want to live in thirty years hence, we are closing our eyes to the necessity of change. We allow change only where there is an immediate threat of being overwhelmed by current events. We have, to all intents and purposes, abolished our future in order to cling to the status quo of unsustainable wealth and artificial social peace.

The Little Ice Age

There can be no doubt that the European model has been extremely successful, and this success was based not on Christianity, but on an economic and social model which emerged from what historians term the great crisis of the 17th century, when the Little Ice Age cooled down the northern hemisphere by some two degrees Celsius.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

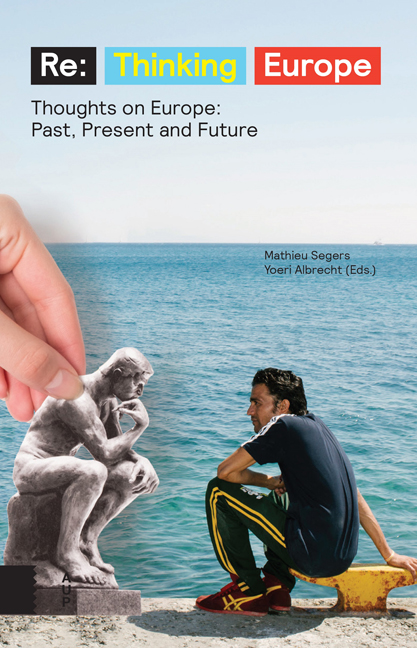

- ReThinking Europe Thoughts on Europe: Past, Present and Future, pp. 121 - 132Publisher: Amsterdam University PressPrint publication year: 2016