On the Identity of the West

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 07 January 2021

Summary

Early in what we call the “modern” era in Europe – in the 17th and 18th centuries – three distinct points of view emerged and contended for ascendancy over minds. They were views laying down different principles for the governance and development of European society. One made the assertion and protection of “natural rights” crucial, another focused on the satisfaction of individual preferences or “utility”, while a third held up the banner of “citizenship”.

By the end of the 18th century the first viewpoint had been asserted in the American Declaration of Independence and revolutionary France's proclamation of the Rights of Man.

The second had been espoused by the English philosopher Bentham, whose “happiness principle” provided the basis for what became widespread movements for legal and penal reform, while the third, associated especially with Jean-Jacques Rousseau, transformed the ancient conception of citizenship into a notion of public morality expressed as a “social contract”.

Not one of these viewpoints prevailed to the exclusion of the others. Instead, they all contributed to what is probably best described as a broad movement of reform directed at the church and state of the ancien régime, in order to create what we would now call a liberal secular order.

Despite important differences between these points of view, on closer inspection they shared one fundamental assumption: the belief in an underlying equality of humans, their “moral” equality. All three took it for granted that the basic, organising social role should be “the individual” rather than the family, tribe or caste. They understood society as essentially an association of individuals. And it is that belief which provided, in turn, the radical, subversive edge of the doctrines they defended – leading those who espoused them into changes which they did not always foresee or welcome. Thus, the assertion of “natural rights” contributed to the later emancipation of women and other minorities and Bentham's insistence that “everyone counts for one and no one for more than one” could become a “populist” majority principle, while invoking Rousseau's “general will” might involve the confusion of freedom and virtue.

Despite these differences and their implications, it is important to remember what they nonetheless shared, the assumption of human equality – of a moral potential inherent in individual agency.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

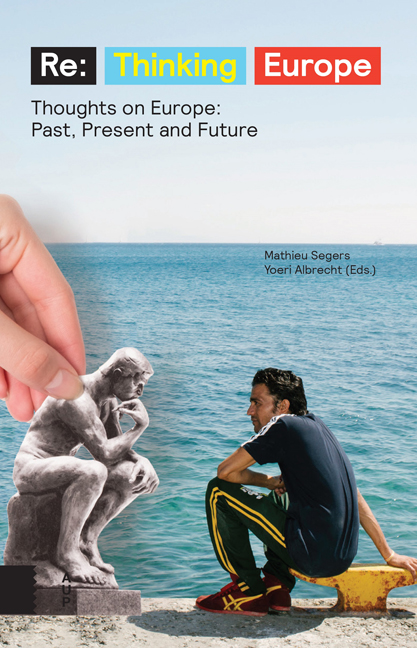

- ReThinking Europe Thoughts on Europe: Past, Present and Future, pp. 73 - 86Publisher: Amsterdam University PressPrint publication year: 2016