Culture and the EU's Struggle for Legitimacy

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 07 January 2021

Summary

Europe's current crises seem to have true potential of splitting the Union apart. The Euro crisis, the looming threat of Brexit, and the refugee crisis have put the legitimacy of the EU and the integration project into serious question in the eyes of many. The EU's multiple crisis has once again shifted the question to the fore of why we are in this together to begin with. What are the ideas, commonalities, and aspirations that unite us? What differences divide us, are they dooming integration to failure, and do they have to be divisive? Might shared ideas, values, and goals help in overcoming Europe's present discontents, or is all lost in the face of clashing interests and incompatible identities? What role might culture play in this?

It is important to see today's crisis of EU legitimacy in historical context. This is what I will try to do in this essay, moving from the foundation of the European Communities in the 1950s to Europe's present discontents. I shall tell a story of how our ideas and standards of what it would mean for the EU to be legitimate have evolved over time ‒ and of the roles that culture has played in these ideas. My story is a tale of how the European institutions, political leaders, opinion-making elites (what I shall refer to as “EU official” discourses) and the wider public in the members states fought over what the point of integration was, what form it should take ‒ and on what grounds it could be claimed to be legitimate. I trace processes of meaning making, by which some ideas become more important than others in how we make sense of the EU and its legitimacy. Culture has played key parts in various of these competing ideas around EU legitimacy, not least in many claims that the Europeans form a community, and not only because they share a joint project, but also because they share common values and ideological commitments ‒ and that, therefore, integration and a common European polity are justifiable.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

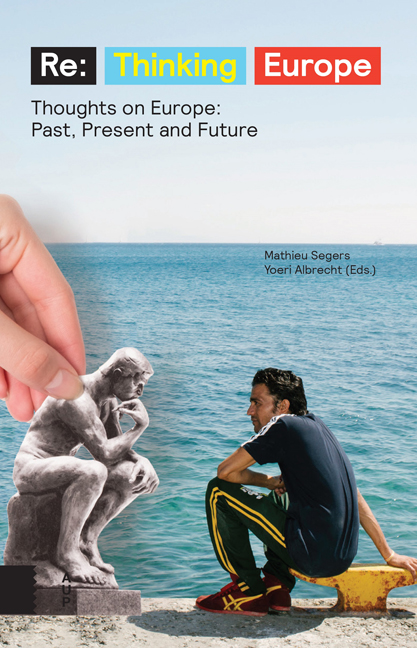

- ReThinking Europe Thoughts on Europe: Past, Present and Future, pp. 155 - 168Publisher: Amsterdam University PressPrint publication year: 2016