Afterglow of a Dead World: Memories of the future

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 07 January 2021

Summary

Would you allow me to begin by sketching my background.

I am a child of Protestant parents; indeed, my father was a minister. Looking back from this century, I have the feeling that the simple Latin vocative of the word “mister” may sound to you, reader, as though it alludes to an exotic species at the zoo, a rock from space, or an artefact in a display case with objects from the Humanist Christian Civilisation…

Anyway, my father was the child of the petite bourgeoisie, and as such he harboured sympathies for the social-democrats who, in his youth, continued to preach the elevation of the people, but whose overwhelming banality instilled in him, from the 1970s onwards, an ever greater distaste. When he died in 2010, he considered himself to be non-partisan.

I am digressing a little, but digressing is the only way to get to the point, at least if you’re me.

Around the time that my father grew estranged from “the left”, I travelled to Prague as a student with a couple of friends, spurred on by curiosity and armed with notions about the true, or at least less untrue, communism.

Little mother Prague disclosed herself to me on a grey February day in the year 1976, if memory serves. We’d headed off on the hoof, poorly prepared but in possession of a visa, and leaving head-shaking parents in our wake: no one travelled behind the Iron Curtain of their own accord, where the world was cold and cruel. We’d seen their anxiety in our early puberty, when the Russians crushed the Czechs’ desire for freedom beneath their boot heels, but at the same time, we felt that right-wing propaganda in the West was greatly exaggerated.

It was already growing dark – it had been growing dark all day – and my two friends and I drove through the dimly lit centre of the city in search of a hotel.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

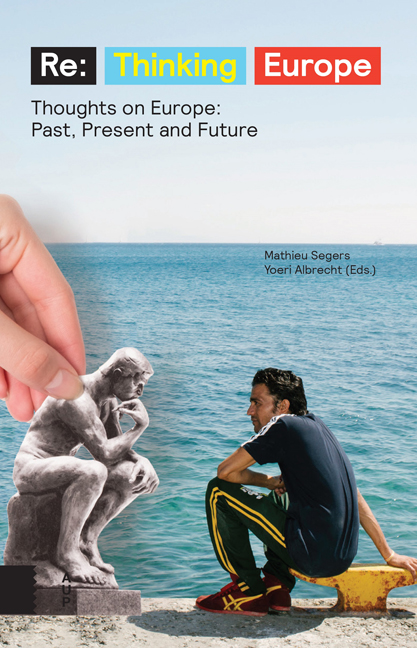

- ReThinking Europe Thoughts on Europe: Past, Present and Future, pp. 99 - 108Publisher: Amsterdam University PressPrint publication year: 2016