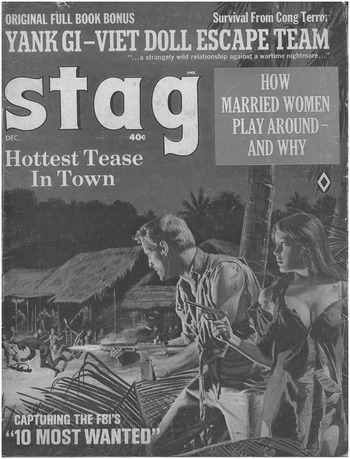

Under a darkly lit night sky somewhere in Vietnam, an American GI leans his back into the trunk of a palm tree, forest green elephant grass concealing part of his well-toned body. His torn shirt exposes a muscular yet bloodied shoulder, though his resolute face suggests he has little inclination to deal with his wounds right now. Next to him stands a slim, attractive brunette woman with Eurasian features. Her clothes also are ripped, a short red dress shredded to reveal her shoulders, chest, stomach, and thighs. Whereas she holds a pistol in her hand, the American lurches forward as he sprays bullets from his semiautomatic rifle into a thatch-roofed building. Communist soldiers fall to the ground as expended shell casings arc up from the rifle’s ejection port. Our hero has taken his prey completely by surprise. The woman beside him appears calmly pleased.

So ran the cover art for the December 1966 issue of Stag magazine. Mort Künstler’s depiction of combat action in Vietnam is alive with color – the darkened blue sky, the hot orange flash from the rifle’s muzzle, the woman’s crimson red dress. In bold yellow letters, the cover exclaims that this month’s original full book bonus centers on a “Yank GI–Viet Doll Escape Team,” a tale of survival in the face of “Cong terror.” Readers are promised a “strangely wild relationship against a wartime nightmare.” The accompanying story from pulp writer W.J. Saber does not disappoint, while an offering from “Stag Confidential” a few pages later reinforces the underlying message from both Künstler and Saber. “More than any war yet fought by U.S.,” the short piece advises, “the Viet War is one of small units, and there is a great chance for heroism by enlisted men, right down to the greenest of draftee privates.”1

At the same time the US Military Assistance Command in Vietnam (MACV) was arguing that 1966 might mark a “turning point in the fortunes of this strange and difficult operation,” men’s adventure magazines were leaving the impression that wartime events still could produce heroes worthy of praise and sexual reward. True, MACV acknowledged, the communist enemies continued their efforts in “terrorism, harassment, sabotage, propaganda, and small hit-and-run attacks aimed at controlling the population and blocking any significant gains in [South Vietnamese] nation-building.”2 But the macho pulps shared widely held convictions that young American soldiers nonetheless could find a man-making experience in the jungles, rice paddies, and villages of South Vietnam.

Many GIs, however, soon would come to realize that the depiction of combat advanced in the macho pulps left much to be desired. While senior military officers, like General William C. Westmoreland, argued that the war in Vietnam could not be won by military solutions alone, men’s mags portrayed a conflict that looked eerily familiar to the conventional battlefields of World War II. In the magazines, the political aspects of irregular warfare seemed ill-suited for offering young GIs the chance to prove themselves as men. In fact, pulp writers hardly, if ever, mentioned the multilayered political war in South Vietnam. Likely, few authors had a deep understanding of Vietnamese politics. Plus, it would have been easier for them to rely on well-established tropes where real men defeated their enemies in a standup fight. Thus, adventure mags such as Man’s Illustrated published exhilarating stories like “Riding Shotgun in Helicopter Hell,” where chopper missions against the Vietcong meant having to “fly like a pilot, dig-in like a GI – and fight like a Marine.”3 Presumably only a small number of readers would have been excited to negotiate like a diplomat.

For those young men concerned about proving themselves in Vietnam, the reality of war there must have been disconcerting in the extreme. The experience of combat did not relate so easily to the triumphal rhetoric in magazine articles and illustrations. Without question, the macho pulps were not alone in offering up an unrealistic version of Vietnam, one official chronicler describing National Geographic’s wartime coverage as “innocent.”4 Adventure magazines, though, stood apart by reinforcing narratives where traditional accounts of battlefield combat remained central to waging war, all while offering readers a supposedly tried-and-true method for attaining their manhood. There was one problem, however. Vietnam failed to deliver.

The American experience in South Vietnam exposed the lie of pulp war stories. Sons came home thinking their World War II fathers, so prevalent in the magazines, had somehow deceived them, their initiation into manhood betrayed by a gruesome, deadly, and ultimately unsuccessful war. One veteran recalled being shocked that the Vietnamese looked upon him with fear and hatred. “I still naively thought of myself as a hero, as a liberator.”5 In many ways, the war in Vietnam proved implicitly frustrating to Americans, but arguably more so for young men raised on the images and storylines perpetuated in adventure mags. For these “warrior teenagers,” the conflict had failed miserably to live up to expectations spawned by their fathers’ generation.6

Worse, Vietnam apparently had disappointed boyhood dreams wherein war’s man-making experience shepherded postwar veterans into a close-knit “band of brothers” who reaped praise and admiration from the society sending them off to war. “We went to Vietnam as frightened, lonely young men,” William Jayne remembered. “We came back, alone again, as immigrants to a new world.” Thus, neither the Vietnamese whom Americans ostensibly came to help nor antiwar civilians back home had regarded these GIs as valiant and noble heroes. The pulps, it appeared, had been nothing more than provocative fiction all along.7

The New Face of War

Western notions of Southeast Asia long had been colored by racialized interpretations of recalcitrant and politically immature native peoples. French colonizers, who formed Indochina in the late 1880s, viewed the ethnic Vietnamese as primitive, effeminate, and lacking initiative. Americans tended to agree. One consul reported to Washington, DC in 1924 that the inhabitants of central Vietnam “as a race are very lazy and not prone to be ambitious.” Such depictions clearly spoke in racialized terms, hardly considering the political and social complexities of a multifaceted Asian community grappling with the consequences of European colonialism. Moreover, raw power undergirded the tense relationship between West and East. French imperialists held dominance over their Vietnamese subjects, extracting natural resources to benefit the metropole while the local rural population bore the brunt of foreign rule.8

All that changed in World War II as Japanese invaders unseated the French colonial state to impose their own brand of imperial rule. Vietnamese nationalist groups – including the powerful communist Viet Minh under Ho Chi Minh – saw in this wartime upheaval their chance to claim independence. In September 1945, after Japan’s unconditional surrender to the allies, Ho proclaimed a Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV), free from foreign influence. The French, however, were intent on regaining their possessions. Fearing the loss of western-oriented Asian nations to communist aggression, the Truman administration offered France economic assistance and political backing in their plans to retain Indochina. While the resulting French-Indochina War (1946–1954) ravaged the Vietnamese countryside, American officials worried the conflict was auguring in a new era of communist-inspired revolutionary warfare. They were not to be disappointed. Despite massive US assistance, the French could not maintain their colonial holdings, leaving behind two competing political entities, North and South Vietnam.9

While Ho Chi Minh consolidated power in the communist north, Ngo Dinh Diem fought to gain supremacy in the politically fractious south. Diem’s anti-communist fervor appealed to Americans anxious about the larger Cold War competition and helped ensure external backing when the government of South Vietnam (GVN) needed it most. Even with his gains, though, an internal insurgency slowly grew to challenge Diem’s rule. While Ho remained hopeful of unifying an independent Vietnam, the Hanoi Politburo debated how best, if at all, to support their southern brethren. By the early 1960s, the National Liberation Front (NLF) had taken root across much of the South Vietnamese countryside, placing the military struggle on equal footing with their political efforts. The armed faction of the NLF, the People’s Liberation Armed Forces of South Vietnam (PLAF), soon followed with a campaign of targeted assassinations, subversive political activity, and even armed attacks against Diem’s governmental outposts and army bases. South Vietnam was inching closer and closer to full-scale war.10

While the PLAF – pejoratively dubbed the Vietcong, or VC, by Diem and his American allies – increased their assaults against the GVN, the Kennedy administration sent thousands of US advisors to South Vietnam in hopes of stemming the communist tide. By 1963, there were more than 16,000 American military personnel in country. The situation only deteriorated in November when a military junta overthrew Diem in a bloody coup, leaving the countryside in a state of political turmoil. Hanoi, sensing an opportunity, boosted its support to the NLF and slowly began infiltrating North Vietnamese Army (NVA) units into the embattled south. Kennedy’s assassination, only three weeks after Diem’s, left President Lyndon B. Johnson little choice, so he believed, other than to continue supporting America’s Southeast Asian ally. By mid 1965, US ground combat troops were deploying to South Vietnam, soon to turn the country into one of the bloodiest battlefields of the Cold War era. America once more was at war.11

There is little in men’s adventure magazines to suggest that pulp writers fully appreciated the nuances of the political and military origins of America’s war in Vietnam. Rather, they focused on repurposing the soldier-hero image of World War II. If John Wayne had boosted morale back in the 1940s with tales of individual heroism, might he be able to do so again two decades later? The Duke certainly thought so, best conveyed in his 1968 film The Green Berets. True magazine called it one of the “most action-packed, realistic war movies ever.” Film critics were far less enthusiastic. Renata Adler, of the New York Times, described the picture as “vile and insane … so full of its own caricature of patriotism that it cannot even find the right things to falsify.”12 By the time of its release, soldiers in Vietnam tended to agree with Adler. Wayne’s movie seemed more surreal propaganda than an accurate rendering of a complex war. The pulps, though, stayed on message. Just one year before the film’s release, Male shared a story on Green Beret Sergeant Harold T. Palmer, a “tough, two-fisted” commando who “rallied his battered and bleeding band of GIs” to launch a million-to-one assault against the “steel-toothed jaws” of a Vietcong death trap.13 Men’s adventure editors still believed martial heroism could sell magazines.

They were right. In Vietnam, the officials running the post exchange (PX) system chose which magazines to stock, and how many copies, by referring to stateside Audit Bureau Circulation data, sales returns, and soldiers’ reading habits. Clearly, GIs were consuming plenty of reading material, an average of thirty sea-vans of periodicals being delivered to a Saigon warehouse each month for distribution to fifty-eight outlets across South Vietnam. Major categories included news periodicals like Time and Stars and Stripes, general interest offerings like sports and comic books, and adventure monthlies which included “girlie magazines.” Officers debated what was considered in “good taste” and thus conflated “sex titles” with macho pulps because the latter included racy photo spreads and salacious articles.14 As one senior staff officer disappointedly noted, “Reasonably good magazines are disappearing and there is a proliferation of trash.” Readers, though, made their preferences known. In 1967, thirteen of the top twenty best-selling magazines in the PX system fell into the men’s adventure category. By April 1969, the rankings had changed little. While Playboy, perhaps unsurprisingly, topped the list, adventure mags filled most of the remaining spots, each selling in the tens of thousands every month – Cavalier, Climax, All Man, Stag, and For Men Only to name but a few. Annual magazine sales reached $12 million, which yielded a hefty profit for the private contractor Star Far East Corporation.15

No doubt soldiers consumed these magazines for a variety of reasons. One US Army survey found that younger readers were “satisfied with the ‘girlie-type’ magazines,” whereas older readers preferred Newsweek and Popular Mechanics.16 Newly arrived recruits may have been searching for examples to follow in combat, hoping to be inspired by tales of courageous Green Berets besting their Vietcong enemies. Others may have focused on the sexy cheesecake photo spreads, or simply have perused ads for items to purchase or jobs to fill once back home. Regardless, soldiers were consuming adventure magazines in massive quantities, and not just in Vietnam. The Korean Regional Exchange (KRE) similarly ordered pulps by the thousands. In 1969, KRE’s annual requisition left little doubt of the pulps’ continuing appeal – 45,600 copies of Stag, 42,000 of For Men Only, and 30,000 of Real Man. Senior military officials may have considered them “low quality magazines,” but American soldiers overseas buying the macho pulps evidently thought otherwise.17

If the sheer volume of men’s adventure magazines in Vietnam contributed to soldiers’ false expectations of combat, pulp writers at least acknowledged that this was a new kind of war. Skipping over the political origins and aims of the NLF, the magazines concentrated on what appeared to be the distinctive nature of combat in Vietnam – guerrilla warfare. Even before US ground troops arrived in Southeast Asia, Stag was calculating that one guerrilla equaled 400 soldiers. In 1963, Brigade described a “phantom war” where entire villages were “being massacred by the Congs when the headmen are suspected of cooperating with the Saigon government.” US advisors were not even sure how many of the enemy existed in such a “sonofabitching war.” One lashed out against the NLF for conducting raids “like wild animals on innocent civilians.” The people, men’s mags argued, were living in terror. Guerrilla war was a “pestilence of the human race,” the “cruelest form of warfare on earth.”18

Once ground combat troops arrived in force, Americans wondered if GIs were prepared to fight and win in what veteran ABC correspondent Malcolm Browne called a “different kind of conflict.” Clearly, the United States’ stockpiles in H-bombs and ICBMs were ill-suited to the guerrilla war inside South Vietnam. Stag thus ran a 1966 story on “simple, unsophisticated hardware” such as grenade launchers, walkie-talkies, and even hatchets, weapons more appropriate to the “brutal in-fighting that is the key to GI life and death.”19 That same year, Male introduced readers to the subterranean efforts of the “tunnel rats,” who were fighting a “new kind of war, so terrifying and dangerous that it makes above-ground combat in Viet Nam look like a field exercise.” If the enemy appeared inhuman, some in fact were. While soldiers and marines employed newfangled “radar personnel detectors” against the Vietcong – “They were after our throats,” said one infantryman – Stag published a short piece on a “new terror for GIs in Vietnam.” According to the story, a marine corporal on patrol near the demilitarized zone was mauled by a tiger. Browne clearly was on to something. This was a different kind of war.20

Pulp writers were not alone in their struggle to make sense of such a disorienting experience. The war’s incomprehensibility even left soldiers and marines unsure why they were in Vietnam. As veteran James Webb wrote, the conflict felt “undirected, without aim or reason.”21 Sure enough, men’s mags also failed to grasp the larger strategic and cultural nuances of this new kind of war. In the late 1950s, as authors were writing in the aftermath of the French-Indochina conflict, pulp war stories focused on the genre’s basic pillars. One tale related the exploits of an American pilot captured by the Viet Minh who spent six months with the “guerrilla women of Viet Nam.” For Men Only shared the combat diary of a French paratroop commando, while Battle Cry criticized US politicians for not supporting French forces at the climactic battle of Dien Bien Phu. None of these articles offered insights into the Vietnamese civil war, instead focusing on how the Reds were intent on taking over Southeast Asia.22

On the eve of full-scale American deployments to Vietnam, when the macho pulps did venture into the strategic realm, their prognoses seemed based more on hope than evidence. In February 1965, Male opined that the “Viet Cong Reds [might] fear a Chinese communist invasion even more than an American invasion.” While the relationship between Hanoi and Beijing could be prickly, this was pure speculation at best. True, the communists did worry about their neighbors to the north, but the DRV was far more concerned in 1965 about a US incursion than a Chinese one. That same issue, Male struck an optimistic chord. “As bad as things look in Viet Nam, some of our military men hope that the country can hold together just a little while longer.” Citing food shortages and low morale, the magazine suggested that the northern communists were in deep trouble. And never mind, Male told its readers, if the situation worsened – “we could win the war, just by ‘gutting it out.’” No doubt more than a few senior policymakers in Washington, DC felt the same way.23

Besides, “gutting it out” is what real men did, at least according to the pulps. How could a young recruit prove his manhood in battle if he wasn’t tested, pressed to his limits, before coming out victorious? In Vietnam, though, simply withstanding pain did not equate to military or political progress. Along the way, the very definition of heroism seemed to be changing. By the time of The Green Berets, John Wayne’s military antics on the big screen were provoking ridicule from soldiers in the field, not admiration. Being “gung ho” was less important than having a “good head.”24 One lieutenant differentiated his men from “those phony popcorn heroes in the movies who go down fighting to the end.” Another GI recalled how the “whole John Wayne thing went out the window” after his first taste of combat.25 All this despite the continuing brisk sales of men’s adventure magazines within the Vietnam PX system. Old habits die hard, and no doubt, for some, the pulps remained popular for the escapism they offered. Not until the early 1970s would they eventually fall out of favor with their prospective readers. For far too many young GIs, the allure of martial masculinity remained strong throughout the 1960s, despite the deadly, countervailing evidence provided by combat action in Vietnam.

That combat was proving far different than the set-piece battles of World War II and Korea. One Department of Defense study found that more than ninety-five percent of communist attacks occurred below the battalion level, a clear indicator of the unconventional fighting style preferred by the Vietcong. Moreover, in a war without front lines, intelligence analysts struggled to maintain a clear picture of the enemy situation. Bill Ehrhart recalled how it was like putting together a “jigsaw puzzle from the bits and piece of information that poured into” his operations center.26 Each time Americans departed an area supposedly cleared of enemy forces, the VC drifted back again to regain influence over the population. One veteran had the feeling “the blind were leading the blind.” Male even surmised that the lack of progress might be the fault of the US Army’s infantry schools, which “emphasized conventional warfare, not dirty jungle guerrilla tactics.” On frustratingly long marches, GIs scoured the countryside, more often than not returning to their bases empty-handed with no “trophies” to show for their efforts.27

Despite the incongruences between World War II and Vietnam, the adventure magazines’ narratives remained wedded to earlier conceptions of warfare even as they occasionally offered more realistic assessments of the current conflict. Stag, for instance, shared the optimism of “Pentagon old-timers” who felt the war would be won “because of our greater maneuverability. It takes the Cong ten days to move three of its battalions. The U.S. can move five battalions in a day. The result is that ten American battalions can fight 50 Cong battalions.” Left unstated was the obvious reality, at least in 1966 when the Stag issue came out, that the insurgent forces in South Vietnam never considered massing fifty battalions to fight the Americans.28

The following year, pulp writers trumpeted American actions that fit more easily within a World War II-style narrative. Both Saga and Stag ran articles on the 1st Infantry Division’s ten-week excursion into War Zone C, northwest of Saigon, in late 1966. Dubbed Operation Attleboro, the series of battalion-size sweeps ultimately included more than 22,000 American and South Vietnamese soldiers. On one day alone, 8 November, the 1st Division’s artillery expended over 14,000 rounds. Body counts tallied more than 1,000 enemy dead, while the Americans seized 2,400 tons of rice, 24,000 grenades, and 2,000 pounds of explosives. As Saga boasted, when the smoke and flames had cleared, the operation “had been added to the glorious history of the Fighting First Infantry Division.” By the metrics of World War II, American forces were making solid progress against the southern insurgency and their NVA brothers. US operations like Attleboro, however, proved the exception in South Vietnam, and, more importantly, ultimately failed to solve any of the war’s underlying political problems.29

True, Attleboro’s conventional metrics reflected a faith in numbers and statistics so embraced by the US Department of Defense in the mid 1960s. On the ground, however, American soldiers more often encountered mines and booby traps that were left behind by a phantom menace far more difficult to quantify. Writing for True, Malcolm Browne shared GIs’ exasperations with this “new kind of war” where the “waits are long, battles brief, and no one knows when the VC will fight or flee.” Booby traps and mines incited a unique brand of fear. “Like serpents they surround you,” wrote one vet poet. Mirroring soldiers’ memoirs, the macho pulps highlighted the VC’s hidden instruments of death – toe poppers, punji sticks, trip wires, and tiger traps all evidently covered the landscape.30 According to Stag, “forty of 57 wounded in one 199th Light Infantry Company got their Purple Hearts via booby traps.” All told, some twenty-five percent of allied casualties came from booby traps and mines. How could one become a hero, gain a clear sense of triumph, when the war’s main threat came from deadly, inanimate objects? One young soldier from the 1st Infantry Division recalled the infuriation of losing buddies to an enemy he could not find. “It was very frustrating because how do you fight back against a booby trap?”31

The fact that Americans could not distinguish between friend and foe in a foreign Asian land only made matters worse. Contemporary racial attitudes did not help. Wartime racism, a tradition dating back to the colonial era, was not hard to find in men’s adventure magazines. During and after the Korean War, the pulps ran autobiographical sketches from GIs who had “smacked the Gooks in the guts with everything we had” or had flown suicide combat missions in “Gook Alley.” World War II vets chimed in with their experiences in the Pacific, one taking pleasure in finding two “Gook guerrillas” and cutting them “to pieces.”32 Whether Japanese, Korean, or Vietnamese, any darker-skinned adversary could be linked back to the original mythic race-enemy, the Indian. The pulps were not alone in conflating racial foes. In the Captain America comics, for example, when Cap first encounters Japanese soldiers, they are posing as Native Americans. No wonder, in an odd twist, that Battle Cry highlighted a Sioux GI serving in Korea who collected “commie scalps” while fighting the Chinese Reds. Racist perceptions shaped much of American thinking during the Cold War era.33

If the enemy-as-savage metaphor made sense to many GIs fighting in Vietnam, the vast majority discovered they had little if any prospect of actually joining in the contest. Sold by the pulps that Vietnam, like World War II, would offer them a man-making experience, readers who deployed to Southeast Asia found they rarely made it to “Indian country.” At least seventy-five percent of American troops in Vietnam never saw combat. Instead, most of them served on large bases where they could enjoy ice cream shops, basketball courts, and service clubs. Could one really become a hero on the Long Binh post softball field?34 Bluebook noted the support ratio in a 1967 article, yet still lavished praise on the US fighting squad, “considered by professionals as the most elite military group in the history of American warfare.” For those young men in their late teens or early twenties seeking a chance for martial glory, perhaps they might beat the odds and have the chance to “zap” a VC. Besides, the magazine noted, “Older men cannot cope with the demands of jungle fighting.”35

With so many GIs serving in support units, frontline combat infantrymen predictably cast aspersions toward the rear areas, popularizing a new term in the military lexicon – REMF. While grunts held these “rear echelon mother fuckers” in contempt, living on base camps alternatively could be filled with the threat of mortar and rocket fire or with abject boredom. One infantry officer derisively remarked of REMFs that the “most dangerous thing they’ve got is getting killed in a traffic accident or VD.”36 In the pulps, however, even support troops could break free from their supposedly mundane existence and demonstrate their courage under fire. Male printed a story in which a transportation soldier driving a semi-trailer barrels through enemy barricades to keep a vital supply line open. Leading a convoy, the “Yank marauder” proves that the enemy’s “highway of death” is just as lethal to the Vietcong as it had been to the Americans. For Men Only ran a similarly themed article on a rugged, no-nonsense engineer officer unplugging trouble spots to feed ammunition and supplies to the battlefield. Vietnam might be a different kind of war, but in the pulps, at least, every GI had a chance to find meaning by undertaking a dangerous mission against a battle-hardened enemy.37

Battling the Cong

Pulp readers must have wondered how the People’s Liberation Armed Forces of South Vietnam came from such an ostensibly lazy, effeminate society, when the Vietcong, in contrast, seemed bred for war. One general officer ranked both VC and NVA soldiers as “the best enemy we have faced in our history. Tenacious and physically fit.” A young lieutenant serving with the 25th Infantry Division in 1967 agreed, sharing with war correspondent Robert Sherrod his amazement of the Vietcong’s grim resolution: “I just don’t understand what motivates these people.” Americans may have conceptualized their Vietnamese foes through racist lenses, but any prejudices did not stand in the way of bestowing upon the VC a grudging respect. Here was a steadfast and capable opponent.38

Even before American combat troops deployed to Vietnam, men’s adventure magazines portrayed the Vietcong guerrilla as “the most amazing soldier in the world. He wears his hair long, rarely shaves, wears filthy clothes, and his skin is full of jungle sores. Yet he can outwalk, and outcrawl any Western fighting man.”39 Male noted how the Vietcong had covered nearly all of the South with camouflaged spike pits and seemed in awe of the enemy’s feats in physical endurance. “If you offered a tank or howitzer to a Red guerrilla in Vietnam he’d laugh in your face,” the mag declared, “turn you down flat. He can average 45 miles a day traveling light, and speed is his game.”40 To ensure that its readers made the connection between the VC and savage frontier Indians, Men shared how it was “not an uncommon sight to see a U.S. helicopter in Vietnam brought down with an arrow sticking in its belly.”41 Nowhere in these portrayals did the pulp writers discuss the revolutionary struggle’s political component. Perhaps such omissions help explain how young lieutenants could not fathom their enemy’s motivation.

As the American war got under way, the macho pulps continued to highlight the Vietcong’s competence, while never overlooking the evils of communism. Male revealed how the devious “Cong” targeted green American troops by hiding grenades in beer cans, spiking water with glass splinters, and even packing coconuts with TNT. True Action described the local VC in Pleiku province as “a murderous army of raping, kill-crazy Cong [that] was ruthlessly plundering the countryside.” Their leaders were “butchers” or “sadistic, scar-faced Communist cut-throats” who brutally slaughtered anyone among the rural population foolish enough to challenge their power.42 Moreover, to demonstrate Hanoi’s role in this war, adventure mags were sure to highlight the communist aggression from North Vietnam. In one account, an inspection of dead guerrillas found they were not southern insurgents, but rather carefully selected agents from the North Vietnamese Intelligence Bureau – “the equivalent of Ho Chi Minh’s own KGB.” Thus, the pulps could more directly tie the external threat from Hanoi to their communist masters in Moscow. Of course, the relationship between the two capitals proved far more intricate.43

These competing interpretations of the Vietnamese communists – praiseworthy fighters yet brutal savages – left an ambiguous message to both pulp readers and deployed GIs. Australian correspondent Phillip Knightley believed that “racism became a patriotic virtue” in Vietnam, helping explain the common epithets of gooks, dinks, and slopes. And yet the “pint-sized VC” remained a “tough and aggressive foe even after capture.”44 If they did not fight like real men, refusing to “come out in the open and fight,” they also could mount ferocious counterattacks when surrounded by American or South Vietnamese units. One typical marine captain was astonished by the “bravery of some of those little guys.” What then to make of elite American units that copied the enemy’s skulking way of war?45 True showcased a team of US Navy Seals who had “adapted Viet Cong tactics” on their long-range patrols. Did these American warriors become less masculine in the process? Apparently not, as by story’s end, the Seals had gained an edge over their enemy. As one sergeant claimed, “There’s no better feeling in the world than knowing you are able to live and fight like Charlie and beat him at his own game.”46

Unfortunately for the US military command in Saigon, their South Vietnamese allies had yet to match the proficiency of the communist foe. American condemnation for the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) was near universal. GIs considered ARVN soldiers and their leaders corrupt and lazy, lacking morale and bravery. Regional and Popular Forces, akin to local militia, fared no better. “They aren’t worth a fuck,” growled an American.47 One veteran from the US 25th Infantry Division emphasized the distrust many felt toward the ARVN: “They were losers. They didn’t have any initiative whatsoever.” As with so much in this war, the reality proved far more complicated. South Vietnamese soldiers were underpaid, many questioned the legitimacy of their own government in Saigon, and most lacked effective ideological training so they might more readily embrace the national cause. Still, ARVN units fought tenaciously to the bitter end, a sure sign that when properly led and motivated, the South Vietnamese were just as capable as their communist enemies.48

The pulps, however, sided with American critics. During the pre-1965 US advisory period, men’s magazines derided the “Arvins” who “jumped like scared rabbits” – a popular refrain among GIs. Stag doubted the trendy idea of extending the war into North Vietnam because of the ARVN’s supposed poor worth. “We can’t get the South Vietnamese to fight on their own soil. What makes anyone think they’ll do better in enemy territory?”49 As the first American combat troops began their deployments to Vietnam, the story only worsened. In June 1965, Man’s Magazine published a piece on the “Sheer Hell in Vietnam.” While the US marines fared well in this battlefield account, ARVN soldiers took it on the chin. According to the mag, GIs were risking their necks for an ally who “can’t or won’t fight” and “who – in some cases – WANT to die!” If the US military command was going to lose this war, a convenient scapegoat already was forming in military circles and in the popular mindset.50

As the war dragged on, estimations of the South Vietnamese only deteriorated. American advisors working with the ARVN saw their assignment as a “thankless and unrewarding job.” Increasing desertion rates did not help matters, nor did the fact that battlefield initiative seemed ever outside of the ARVN’s reach. Incredibly, as Stag related, American officers were admitting in private that “they wish they had the North Viets on their side, instead of the South.”51 In True, correspondent Malcolm Browne called the ARVN a “military white elephant, increasingly content to let the U.S. pay the cost of battle in blood as well as money.” Even after shaming their allies, the Americans still had to take charge of tense combat situations. In one pulp story on the Green Berets, “tall, rawboned” advisor Major Charles Beckwith finds a “scrawny” South Vietnamese soldier feigning a wound during a weeklong battle. “You damn coward!,” the American roars. “Get your butt out there and fight like a man!” For the remainder of the fight, Beckwith keeps a cocked .45 pistol in hand to ensure the unscathed “smiling wounded” do not scramble aboard evac helicopters and take the place of critically wounded men.52

If the South Vietnamese were falling short in proving their manhood in war, the communists apparently had no such trouble. Even the Vietcong who defected seemed more adept than the Americans’ true allies. Dubbed Kit Carson Scouts, former communist fighters who agreed to fight alongside US soldiers and marines made a positive impression on their new colleagues. True, some officials worried about the converts’ fidelity, one officer wondering aloud how “the Vietnamese could switch sides so easily.”53 Yet, through hard fighting and sharing information on the insurgency network, the Kit Carsons normally won over skeptical Americans. Male even published a story on a marine staff sergeant working alongside Vietcong defector Thuong Kinh. After establishing himself in the field on a trial basis, Thuong becomes an integral part of the squad, a “human bloodhound” who leads the Americans through thick foliage, all while avoiding snipers and booby traps. Throughout several engagements, the scout proves “his worth with his uncanny knowledge of enemy tactics and trickery.” By story’s end, Thuong is credited with thirty-one kills, helping turn a potential defeat into tactical victory by spotting a VC ambush.54

If South Vietnamese soldiers appeared reluctant warriors compared even with Vietcong defectors, one ARVN unit did stand out – the Rangers. The macho pulps lavished praise on these elite detachments that ultimately earned eleven US Presidential Unit Citations. Unlike the bulk of the South Vietnamese armed forces, these rugged troops were “more than a match for Communists in hit-and-run fighting.”55 They also seemed ruthless warriors. Male included a full-page photograph of an ARVN ranger jamming a Ka-Bar knife against the stomach of a bare-chested Vietcong guerrilla during an interrogation session, the muddied prisoner visibly wincing in pain. Bluebook highlighted the “incredible valor” of the 44th Ranger Battalion, a group of “Satan-spawned killers” who never quit, even when wounded. Of course, US mentors often hovered nearby, ready to offer support and sage advice when the fighting escalated. Yet, despite the Rangers’ praiseworthy actions, Americans still worried these elite units might falter once their advisors withdrew from the war.56

Adding insult to injury, the political situation looked more appalling than the military one. A seemingly fractious, incompetent, and corrupt Saigon government conveyed that it was doing its best to undermine American efforts in political reform. In reality, GVN leaders inevitably were struggling with the competing demands of building a stable political community in a time of war. Their American benefactors, officially there to help, only proved to NLF propagandists, and far too many rural villagers, that Saigon was nothing more than a puppet of the United States. For Men Only deemed the propaganda war “almost impossible to fight” because the Vietnamese population had taken so much abuse from the French and their own corrupt regime that “they find it hard to believe we’re any better.” Charges of unrestrained corruption and a rampant black market even incited calls for the Americans to “throw a really tight blockade around Saigon.”57

Could it be that the problem was less political than inherently cultural? At least some pulp readers believed so, perceiving fundamental flaws in the South Vietnamese makeup. A Boston resident wrote to Man’s Illustrated in early 1965 sharing his disgust with the “hell of a mess” in Vietnam. The solution, however, seemed evident: “if the people of that God-forsaken country wanted to do something about the Communist Viet Cong they could get off their asses and get to work.” While the Americans were doing “everything humanly possible” to help win the war, their sacrifices clearly were not being matched. According to the reader, the southern Vietnamese “are probably the laziest people in the world.” If the US mission in Vietnam was hoping to build domestic support for a long war of political attrition abroad, they still had plenty of work to do.58

These concerns over the GVN’s fitness to govern had to be balanced with the prevalent view that all communists were inherently evil and impulsively cruel. If ARVN soldiers were inept “good” Asians, then the Vietcong must be deemed ruthless “bad” Asians. Thus, Man’s Action offered a story on the “naked terror” of VC “butchers” who mutilated three US Green Berets and dismembered local civilians.59 Stag ran an analogous piece in which members of the NLF abducted the daughter of a village chieftain friendly to the Americans, and cut off her arm “as a means of frightening the villagers into silence about the Cong whereabouts.” The same issue noted how “Cong pilots” – the NLF had no air force – were being trained by Russian air heroes, a reminder that the Vietnam conflict still should be placed within the larger narrative of the communists’ bid for world domination.60

While the NLF did engage in terror tactics, most infamously at the Hue massacre in early 1968, men’s mags tended to mislead their readers by delineating clear lines between assailant and victim. Yet the fighting in Vietnam never proceeded so neatly. One US marine believed that both sides had made a “habit out of atrocities,” while another veteran judged that his enemy “never cared whether he lived or died… We’d shoot them, and y’know, they just didn’t care. They had no concept of life.”61 In the pulps, however, the war seemed far more black and white. Like the Nazis or Chinese communists before them, the Vietcong were fundamentally wicked. By 1967, this lack of nuance even could break into fantasy. Despite the war’s obvious stalemate, Male recorded that the Americans had turned the tables on the NLF and were winning the intelligence war. “By just feeding a card into a computer, U.S. commanders can find out anything they need to know about any Cong unit.” Nothing could have been further from the truth.62

In actuality, the communists too often held the basic tactical initiative. American patrols might be “in the bush incessantly,” yet only make contact with the enemy when they stumbled into an ambush. The macho pulps told a different story, one in which Americans consistently were on the offensive and making sound progress across most of South Vietnam, whether in the Central Highlands or the Mekong Delta. Often noting how GIs were beating the Reds at their own game – even though many soldiers deemed ambushes an inferior, cowardly form of warfare – men’s mags argued that US counterguerrilla tactics could lead to a war-winning strategy.63 A 1967 pulp exposé on Lt. Richard Marcinko, author of the popular Rogue Warrior series in the 1990s, illuminated how “darkly handsome,” deadly Americans were operating successfully behind enemy lines. Male praised this “Cong-killing” Seal team as a group of “blast ‘em-and-get-out raiders’” who earned the title “super-commandos of the century.” Marcinko later admitted in his memoir this was an “atrociously written piece of fiction,” yet he also shared how the Vietcong had tacked up wanted posters of him throughout the Mekong Delta after the article was published. Apparently, not only Americans were reading the pulps in Vietnam.64

If the enemy indeed were perusing men’s adventure magazines, their capacity to read did little to change prevailing American attitudes that the Vietcong were nothing more than savages. Every instance of violence only reaffirmed the view that Vietnamese communists, whether from the north or the south, came from a long line of “native cut-throats.” Like the “Moslem fanatics” of West Java or the Mau who “spread terror” in their quest to “drive the white man out of Africa,” the Vietnamese fit well into preconceived pulp notions of beastly others who threatened peaceful civilians overseas.65 Since the adventure mags conflated the southern insurgents with North Vietnamese regulars, they not only obscured the enemy’s point of origin, but helped promote GI opinions that “If it’s dead and it’s Vietnamese, it’s VC.” Of course, in pulpworld, killing savage enemies is what true warriors did best.66

American Warriors

If the 1950s mass consumer society spurred fears of a new breed of lifeless “organization men” blandly following behind their tougher, more resilient forefathers, similar concerns seeped into the US armed forces. With war becoming more complex in the atomic age, critics worried that technocrats, focused more on management than on leadership, would rise to the highest levels of command and somehow forget that victory in battle came from hard fighting. Though the image of the “warrior” may have been changing for some in these Cold War years, the pulps retained the notion that physical violence remained at the core of militarized masculinity.67

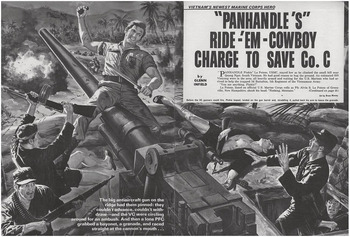

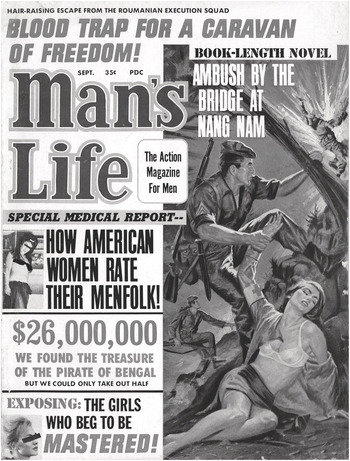

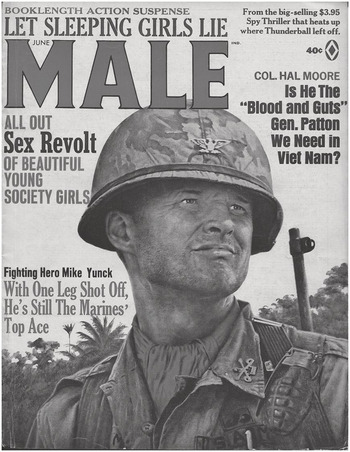

Consequently, adventure magazines heralded strong, individual leaders who could inspire a new generation of American warriors. Stag called Colonel Henry “Gunfighter” Emerson, who commanded a battalion in the 101st Airborne, the “toughest paratroop commando in Vietnam.” Man’s Conquest highlighted marine general Frederick Karch, who had been “blooded in battle against the Japs” in World War II and now was beating “the Reds at their own dirty guerrilla war.”68 Meanwhile, Stag judged Colonel Harold G. Moore, who led American forces at the Ia Drang battle in late 1965, as the “General Patton we need in Vietnam.” Even Patton’s own son, a colonel commanding the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment, received accolades, along with his “Cong-blasting tankers” who were carving out a legend for themselves in the rice paddies and jungles of Vietnam.69

Fig. 4.4 Male, June 1966

No doubt this linking to the World War II generation was purposeful. Conflicts need heroes, and Vietnam proved no exception. Numerous veterans recalled being “seduced by World War II,” so it was only natural for adventure mags to feed into this hero worship. They made sure to cover all the bases by trumpeting each service. In their story on the head of the US Army Special Forces, “Tough Bill” Yarborough, Male noted how this “combat wizard” had soaked up jungle-fighting “tricks” in the Philippines and claimed that he had faced some of Hitler’s toughest SS divisions in Tunisia during World War II. Now, he was putting these “Daniel Boone” skills to good use by training “parachutist-ranger-commandos” for military service around the globe. Man’s Illustrated ran a 1965 story on Creighton Abrams, the future MACV commander, his exploits as a tank commander in Patton’s Third Army draping “the cape of a legend around his shoulders.”70

So as not to play favorites, the pulps gave equal time to the US Navy and Marine Corps. Vice Admiral Roy L. Johnson, who “blasted the Reds at Tonkin Gulf” in 1964, had led fighter sweeps over the Philippines, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa. No “paper tiger,” he was the “real thing – teeth, claws and guts.” For their coverage of General Victor “Brute” Krulak, Stag went into detail on the marine’s World War II exploits in the Pacific before noting how he had maintained “the same kind of courage, daring, and military know-how that make his Marines so rough on the Vietcong in Vietnam now. It’s an unbeatable combination.”71 Man’s Magazine ran a comparable story on Krulak’s peer, Lewis W. Walt. In “The Marine the Japs Couldn’t Stop,” Walt steadfastly leads his unit on New Britain under barrages of enemy fire en route to earning the Navy Cross. By 1966, Walt was commanding all US Marines in Vietnam, pulp writer Glenn Infield observing that “the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese already have discovered the general is just as much at home fighting their kind of ‘dirty war’ as he is the more conventional battles.” These heroes’ shared sense of masculinity clearly was reaping dividends in Southeast Asia.72

The correlation between the Second World War and Vietnam meant that even older warriors, outwardly past their prime, still could offer their services to the nation. Lloyd “Scooter” Burke, who received the Medal of Honor in Korea, was forty-one years old when he was shot down in Vietnam. Two years older, Sergeant Major Bill Wooldridge deployed to Vietnam with the famed 1st Infantry Division. Male recorded that this “Human Assault Wave” had fought in the bloodiest battles of World War II and Korea before heading to Vietnam, his “raw courage gut-fighting repeatedly rewarded by a string of medals” on his chest.73 Man’s Magazine more overtly demonstrated how Vietnam offered a chance for older men to continue fighting and validate their manhood. A story on one Korean War vet, Air Force Colonel Devol Brett, noted how he was a “generation apart, an ‘old man’ of 44 who still flew into combat.” Though younger pilots were “skeptical of his heavy, muscular build and his advanced age,” Brett knew there was a place for him in this war. He still could carry the “battle straight to the heart of the enemy.”74

This dream of vaulting over messy, terrestrial battlefields and directly attacking one’s enemy had inspired airpower advocates from the earliest days of World War I, if not before. Modern-day knights, mounted on mechanical steeds, certainly had captured young readers’ attention in postwar aviation magazines, a trend that continued well into the 1960s. One American pilot flying over the rice paddies and canals of Vietnam saw his aerial missions, akin to “old African hunting trips,” as his own “rite of passage into manhood.” A US Air Force fighter jockey shared his deep enjoyment flying with close friends. “They loved being there.”75 Still another flier, Robin Olds, an ace who earned a special feature in Man’s Magazine, wrote in his memoir of being enticed by the “dream of victory in aerial combat.” War might be ugly and brutal, but the F-4C Phantom jet pilot knew there was more to it than just hardware. In the pulp, Olds educates a superior officer, “They’re not going to win with machinery, sir. We’re going to win with men.” No wonder US Ambassador to South Vietnam Maxwell Taylor claimed that Hanoi’s inability to respond to American airpower would demonstrate communist “impotence,” leading to a political solution.76 In the air, as well as on the ground, manly warriors stood ready to defeat Red aggression.

While adventure magazines showcased rugged pilots battling communist MiG jets or conducting bombing runs over Hanoi through a “blast furnace of lethal flak,” they also highlighted death-defying pilots who saved fellow warriors shot down behind enemy lines. This focus allowed pulp writers to impart tales of individual heroism, with downed Americans defending against or evading an approaching enemy. The knight, knocked off his steed, struggles to rejoin the fray, aided by a steadfast companion.77 Stag illustrated the plot line with a story that made national headlines in early 1966. Air Force Major Bernard Fisher was leading a strike of A-1 Skyraiders to aid a besieged US camp near the Laotian border when one of his pilots, Major Stafford Myers, was hit and forced to crash land. Fisher decided to land his own plane on a debris-littered airstrip and rescue his friend, despite his own aircraft being pummeled with small arms fire. Stag called the performance “one of the most heroic – certainly the most ‘impossible’ – rescue of the Vietnam war.” Writing for the New York Times, journalist Neil Sheehan agreed, noting that Fisher might be recommended for the Air Force Cross. On 19 January 1967, he received the Congressional Medal of Honor.78

In a war without front lines, rescuing downed pilots returned drama to an ugly war against an invisible insurgency. Yet knights historically performed best when liberating a fair maiden. The pulps concurred. In one Man’s Life tale, a young Vietnamese woman, Maria Quin Dongh, lives in a small village terrorized by the Vietcong. Her father can identify the insurgents, but remains silent for fear of communist retribution against his family. Five miles away, a group of Green Berets has set up camp and Maria makes the dangerous journey to plead for their help. Of course, the Americans agree, and Maria leads them back, all of them fighting through a VC ambush along the way. After killing some thirty-five communists – who find “there actually are such places as heaven and hell” – the Green Berets free the village from the insurgency’s clutches. Maria is designated a heroine, but the pulp makes clear that the American soldiers are “doing a big, perhaps the biggest part.” The rescue is made significant thanks to the male–female relationship, the Green Berets’ actions reminding Maria and her family that they have rescuing knights standing ready nearby.79

Through similar storylines, the macho pulps could fashion the American war in Vietnam war as a heroic, man-making experience and, at least before 1968, a relatively successful one as well. Writers dusted off World War II narratives in which American GIs excelled at the tactical level. Male ran a 1966 story on a group of “unkillable” marines led by Staff Sergeant Jimmie E. Howard, who received the Medal of Honor for leading a reconnaissance unit behind enemy lines. The tagline was pure pulp splendor – “the V.C. streamed like maggots from the death-night jungles in human sacrifice waves to storm the vital high ground held by one iron-gutted sergeant and a handful of no-quit leathernecks.”80 Not to be outdone, Stag touted that the Vietcong were avoiding US marines “like the plague.” As an indicator of the GIs’ tactical acumen, the magazine reported that army doctors were pleased by the “low incidence of ‘battle fatigue’ or ‘breakdown under stress’” they were encountering among those hardy Americans serving in Vietnam.81

Courageous exploits like these collectively intimated that the United States was making progress in a hard-fought war. In the southern Mekong Delta, sailors in the “brown water” riverine navy were clearing areas of VC influence and eliminating the threat to local villages and their valuable rice supplies.82 Farther north, Male claimed in early 1967, the enemy had “fewer and fewer places to hide and that sooner or later, the only safe places for him will be outside of South Vietnam.” Only occasionally would reality break through onto the magazines’ pages. One account relayed how an American position had come under mortar fire before facing a “savage suicide attack” by a local Vietcong force. Hand-to-hand combat ensues. The cavalry troopers acquit themselves well in this “death embrace” with the North Vietnamese – thanks to heavy doses of firepower – before the enemy disperses, the high body count a testament to the GIs’ skill and bravery. Yet the piece acknowledged that the communists had destroyed a howitzer, badly damaged five others, and inflicted “moderate to heavy casualties” on the courageous defenders. If the Americans were making progress, their enemy was exacting a high price.83

Even after the 1968 Tet offensive, in which communist forces attacked across the breadth of South Vietnam, the adventure mags publicized heroism at the tactical level. Critics believed the attack exposed the irrelevance of US military power in Vietnam, while MACV commander William Westmoreland accepted the fact that the enemy had “dealt the GVN a severe blow.”84 In February, Man’s Conquest published a piece on a handful of brave Yanks in the Mekong Delta who were “turning Ho Chi Minh’s Sea Trail into a corpse-clogged canal.” True Action similarly featured the combat saga of Lieutenant Colonel David Hackworth in May, who thus far had won sixteen medals and was fast becoming America’s “‘No. 1’ Cong Killer.” Though it had been an “uneven battle” to date, both the decorated officer and the magazine seemed optimistic for the future. “Ahead on points,” author Caleb Kingston noted, “Hackworth is looking for a K.O. next time.”85

Properly told, Hackworth’s story also demonstrated that the war in Vietnam remained as meritocratic as World War II. According to True Action, the future combat leader had dropped out of high school at fifteen, forged his birth certificate, and enlisted in the army. Only later did he earn his GED and gain acceptance into Austin Peay State College before securing his officer commission. Thus, even into the 1960s, any young teen might be captivated by the chance to prove his courage, and his manhood, in battle.86

In the pulps, baby-faced warriors certainly demonstrated their grit. A young Indiana hot rodder, “still sporting peach fuzz,” led his platoon in a “brilliant, slashing maneuver” that destroyed half an enemy company. A twenty-year-old former lifeguard, now a marine platoon commander, outraced VC bullets to save his men who were stuck in a burning vehicle. This “Brooklyn boy who started out saving lives in the waters of Coney Island” had gone on “to do the same in the bullet-swept muck of Vietnam.”87 Even the lowliest of privates could excel in the worst of combat situations. Man’s Magazine highlighted the bravery of PFC William H. Wallace, who helped coordinate the actions of an entire infantry company after it was pinned down and surrounded by enemy forces near Dau Tieng. Despite being a radio operator, only Wallace “stood between the survivors of C Company and death.” Two days after the ordeal, the 25th Infantry Division’s assistant commander pinned a Silver Star on the Long Island native, the medal awarded for “an outstanding act of courage.”88

On occasion, the pulps even publicized the valor of minority soldiers fighting in Vietnam. In True Action’s “Grenade-Duel at Cong Ravine,” Sergeant Manuel J. Perez, Jr. led his men after being pinned down in a well-laid ambush. Only twenty years old, the young Latino devised “a new heroic tactic for his soldiers to ponder over: if trapped by the enemy – charge!”89 Stag featured medic Lawrence Joel, an African American soldier who had enlisted in the army back in 1946. The article noted how the “husky six-footer” had grown up in extreme poverty, as “jobs were exceedingly hard to come by” for blacks living in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. Now thirty-seven, Joel found himself serving in Bien Hoa province with the 173rd Airborne Brigade. Like Perez, his unit was assaulted by a superior enemy force and, with casualties mounting among the paratroopers, the twice-wounded medic bravely assisted his comrades, despite taking heavy fire. As Lyndon Johnson later draped the Medal of Honor around Joel’s neck in a March 1967 White House ceremony, the president remarked on a “very special kind of courage – the unarmed heroism of compassion and service to others.”90 Anyone, it seemed, could be a hero.

If these brave Latino or African American soldiers only periodically showed up in the macho pulps, even more rare were stories hinting that American GIs were not performing in exemplary fashion. Contemporary and postwar critics certainly exaggerated the US armed forces’ woes in Vietnam. To naysayers, the signs of disintegration were evident – rampant drug use and racial tensions, high rates of desertion and battle fatigue, and a general feeling of malaise within the ranks. Adventure magazines, however, generally avoided such defamatory topics.91 Perceptive readers may have wondered why most combat stories began with the enemy launching an effective surprise attack, but the pulps retained their faith in the “quietly professional” troops, merely acceding that “it would be misstating facts to say they are ‘gung ho’ about this war and really hate the enemy with a passion.” Only after the 1968 Tet offensive did a few short pieces surface of marijuana use and “pot-smoking” parties among those serving in Vietnam. The heroic warrior narrative left little room for countervailing testimony.92

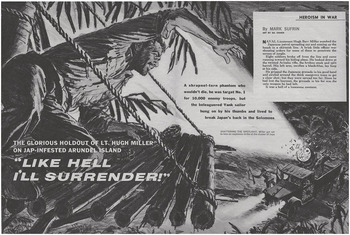

Instead, the pulps sought to highlight fearless men who held true to their nation’s martial values. Prisoners of war emerged as appealing candidates. If some pundits viewed Vietnam as a “war without heroes,” Time assessed that “many Americans were intent on making the prisoners fill that role.” Pulp writers helped lead the memorialization effort, seemingly agreeing with General Westmoreland that POWs “displayed a special kind of long-term valor.”93 As early as 1965, adventure mags like Saga were publishing accounts of captured pilots who “survived a Red nightmare of beatings, nude temptation, and a blood break for freedom.” In March, the magazine ran a story on US Navy Lieutenant Charles F. Klusmann, whose F-8 Crusader was shot down over Laos. Pro-communist Pathet Lao captured the “ruggedly handsome” officer, but his “ill fortune was to prove no match for his determination to survive.” Though surely a humbling experience, Klusmann’s imprisonment offered him the chance to fulfill his own resistance and escape narrative, his courage earning him front-page coverage in the New York Times.94

Another naval lieutenant turned POW, Dieter Dengler, earned two separate stories in the men’s mags, plus a 2010 biography that reinforced the pulp narrative of heroic warrior–sexual champion. “When it came to the opposite sex,” his biographer gushed, “Dieter was a charmer with an unquenchable appetite.” This “inveterate ladies man” ultimately heads to Vietnam where his A-1 Skyraider is downed by enemy fire on 1 February 1966. Captured by Vietcong soldiers, Dengler plans his escape from the moment he is abducted, suffering through bouts of malaria, dysentery, and maltreatment from his captors, one of whom he calls “Little Hitler.” In late June, the lieutenant finally attempts his breakout. Though exhausted, bleeding, and feverish, he evades the enemy for nearly three weeks before an air force rescue helicopter lifts him to safety. Like the World War II captives before him, Dengler has retained his identity as an honorable warrior.95

For a president seeking “peace with honor” as he withdrew the United States from its long, unsatisfying war in Vietnam, calling for the release of brave POWs offered singular political advantages. Richard Nixon skillfully exploited the prisoner issue, hoping to unite Americans at a time when the antiwar movement threatened his plans for an orderly departure from Southeast Asia. Surely, the president was not alone in seeing value – and political capital – in identifying with dauntless men held in captivity. To Air Force officer Robbie Risner, he and his fellow American prisoners endured because they considered their principles more valuable than their lives. Nixon took note. In fact, the release of POWs and a full accounting of those missing in action became a precondition for any peace agreement. No longer a tool for achieving wartime political objectives, American prisoners had morphed into a central aim of the war itself.96

Adventure magazines mostly overlooked this political appropriation of POWs. Their heroism was enough to move popular storylines forward. Like earlier accounts of World War II and Korea, pulps articles concentrated on warriors’ battlefield exploits, leaving discussions on grand strategy or American policy in Southeast Asia to the more high-brow periodicals. When editors and writers did comment on the larger national aspects of the war in Vietnam, they remained categorically supportive, in stark contrast to Hugh Hefner’s monthly. Playboy walked a fine line when it came to the war, sending playmates to tour South Vietnam while its editor ran articles questioning US involvement in the conflict and encouraging a diplomatic solution. The pulps, however, maintained their backing, advocating for perseverance against communist aggression. Besides, they claimed, American GIs were doing their jobs, upsetting the “Cong timetable” and reversing the enemy’s momentum to a point where they might never recover.97

Supporting government policies, like the draft, meshed well with the pulps’ conception of Cold War manhood. To be antiwar was to be decidedly feminine. Such views were not uncommon, one protestor recalling that he heard epithets of “faggots” and “queers” as often as “commies” or “cowards.” One infantryman returned from Vietnam and deemed those who stayed at home as “spoiled, gutless middle class kids who cowered in college classrooms to escape the battlefield.”98 Peace activists like Joan Baez and Jane Fonda appeared in sharp relief to the warriors fighting inside the pages of the macho pulps. Indeed, the contempt many veterans still hold for Fonda is a function of their desire to punish a “dangerous” woman with the nerve to speak out against militarized masculinity. Never mind that it also took great courage not to go to war, best seen in Muhammad Ali’s decision to refuse being drafted. Was Ali a coward? Were the Baltimore Colts football players with a “military problem” acting like sissies as they were quietly enlisted into the Maryland National Guard? Was singer Bruce Springsteen a “yella belly” for viewing draftees as “cannon fodder” and doing his best to gain a draft deferment?99

The pulps seemed to think so, spitting venom at the “bums” who sought to evade or buy their way out of the draft. Saga lashed out at members of the “new left” and the blatant “draft dodging underground” taking hold on college campuses. Man’s Illustrated condemned the “card-burners” and “slackers” who had worked the system to stay out of uniform.100 Male relied on more gendered language as it railed against “guitar-twanging longhairs” who “blast our courageous GI’s in Vietnam, even though the most dangerous weapon they’ve ever held is a banjo pick.” Author Ray Lunt advocated how Americans should “slap down” these unpatriotic complainers lest they influence impressionable kids, “laying the seeds for another draft-dodger generation.” Finally, Bluebook exposed the “draftable young eggheads” who were using every gimmick to “keep far away from the firing line.” Most of these critiques included a not-so-subtle class component, as feminized antiwar protestors seemed to reside mostly on college campuses.101

While the adventure mags rebuked draftees who were trying to duck service through fake limps or staggering into draft boards high on LSD, they conveniently avoided any discussion on the veteran antiwar movement. The Vietnam Veterans Against the War (VVAW) seemed to turn the militarized version of masculinity on its head. When protesting vets marched on Washington, DC in April 1971, for example, roughly 800 of them tossed their medals onto the steps of the US Capitol. As one marine sergeant declared, “We strip ourselves of the medals of courage and heroism … We cast these away as symbols of shame, dishonor, and inhumanity.”102 The disparity between warrior myth and reality could not be more clear. And because more than fifty percent of the vets who joined the VVAW had seen combat in Vietnam, critics could not so easily dismiss them as spoiled, cowardly brats. Men’s mags discreetly sidestepped criticism of these antiwarriors, barely mentioning the growing GI counterculture or the underground newspapers proliferating on military bases. Rather, they published letters from young enlistees who were writing their congressmen in hopes of gaining orders for Vietnam. In the macho pulps, “real” men always stood ready to serve their nation in combat.103

Since antiwar veterans did not reflect gendered notions of military manhood, it is not surprising they were absent from the pages of Bluebook or Man’s Conquest. Yet as the war lumbered forward, year after year in bloody stalemate, it became increasingly difficult for adventure magazines to avoid criticism of US foreign policy in Southeast Asia. Like Playboy, they rarely passed judgment on those US soldiers fighting in the rice paddies and villages of South Vietnam. Occasionally, however, they did speak out against politicians who appeared to be mismanaging the war effort. At the end of 1967, Stag maintained that the fighting along the demilitarized zone between North and South Vietnam had been so murderous for US marines because “political considerations” forced them into defensive positions. If Americans were in an “all-out war,” they would have been able to hit the enemy from the rear, instead of allowing the Vietcong to “simply come out and fight” before disappearing “whenever they like.” Political limitations were not sitting well with pulp editors or their readers.104

Senior military leaders equally bristled at what they considered to be civilian interference. To them, DC policymakers were forfeiting the strategic initiative by “ignoring or overriding the counsel of experienced military professionals.” Political micromanagement seemed at the heart of the generals’ woes. One officer claimed that “policy restraints hindered – if not absolutely precluded – the proper utilization of available forces.”105 In his own memoirs, Westmoreland argued that the president and his civilian advisors had “ignored the maxim that when the enemy is hurting, you don’t diminish the pressure, you increase it.” Both senior officers and the macho pulps thus helped plant the seeds for future arguments that the US armed forces in Vietnam had been forced to fight with one hand tied behind their back. According to Bluebook, the Pentagon even had laser ray guns that, if put to use, would have had Ho Chi Minh screaming for any kind of peace. Warriors in the field apparently had been stabbed in the back by feckless civilians. It would be an appealing reprise for years to come.106

By the late 1960s, the warrior image so central to men’s adventure magazines appeared far murkier than a decade earlier, perhaps even less convincing to young, working-class readers. After the 1968 Tet offensive, the macho pulps generally followed media trends of being more critical of the war, even if the vast majority of articles continued to focus on the individual exploits of brave soldiers and marines. Stag was comparing the rankings of America’s most unpopular wars, while Saga uncovered the “monstrous lie” of Tet’s intelligence failure.107 Cracks in the myth were beginning to surface as more and more Americans questioned the worth of a wretched, destructive, stalemated war. Might it be possible that the pulps had been selling a version of battlefield heroism that scarcely existed in the real world?

The Undiscovered Adventure

War is designed to be traumatic and disorienting. It challenges combat soldiers physically and psychologically, forcing them to confront tensions and fears unlike any other human activity. One reconnaissance specialist remembered his time in the field as an “uncomfortable, chronic, nausea-inducing condition” that came from an unshakeable, “ever-present fear.” It should be of no surprise that twenty-five to thirty percent of all American casualties in World War II were psychological cases. War comes with a cost. In men’s adventure magazines, however, GIs rarely suffered through these emotional ailments. As 1966 came to a close, for instance, Stag lauded how there were “so few mental crack-ups among our troops.”108 Pulp warriors might admit they were afraid in the heat of battle, but those fears never incapacitated them when they were needed most.

Because reality in Vietnam often ran far afield from how the war was portrayed in popular culture, soldiers were forced to reconcile this yawning gap between truth and fantasy, to make the irrational seem rational. In the January 1966 issue of True, not long after the Ia Drang battle, Malcolm Browne commented on the young draftees in their early twenties then serving with the 1st Cavalry Division. “For all of them, combat is a new and terrible unknown.” Surely, some of them must have been excited by the chance to unleash a level of destruction forbidden in their civilian lives. Stag took note later in the year of the “staggering number of rounds fired for every Cong killed.”109 Yet how many of these young draftees would have agreed with Philip Caputo that combat was a far different experience than training exercises? To the marine lieutenant, “the real thing proved to be more chaotic and much less heroic than we had anticipated.” When Stag reported in late 1967 that only half of South Vietnam had been secured despite “close to 100,000 casualties – roughly 12,000 dead – and an investment of nearly 50 billion dollars,” the pulp fantasy must have lost some of its luster. Such measly results for so much blood and treasure exposed fundamental flaws in the magazines’ portrayal of war.110

In large sense, this dichotomy arose because pulp writers and artists were making up their own version of Vietnam. Both the imagined “Orient” and the heroic battlefield were romantic creations conceived in New York City publishing offices. One of the war’s more perceptive journalists, Jonathan Schell, argued that Vietnam had a “dream-like quality” because, like a dreamer, Americans faced a reality of their own making. The dream war in Southeast Asia could be at once dangerous and enticing, full of sensuality and sin, all the while offering opportunities to prove one’s manhood on the field of battle. Long-standing tropes about Western adventurers taming the “exotic other world in Asia” still resonated in the 1960s. Yet the logic never quite added up. When Male argued, for instance, that the US Army’s Special Forces were training the “deadliest and most effective guerrilla fighters in the world,” the magazine also confessed that Americans were having trouble with “difficult Asian tongues.” How was it possible that an unfamiliarity with local dialects did not impede the Green Berets?111

Pulp artists reinforced these fantasies with thrilling illustrations of men at war. The March 1966 cover for Man’s Illustrated showed a grim-faced GI running across a field, M16 rifle in hand, as two Huey helicopter gunships trail behind him. In the background, flames and black smoke rise into the sky, likely from a hamlet set ablaze. For Male’s March 1967 issue, Mort Künstler displayed a US Navy patrol boat careening through a Vietnam river’s waters, an old-fashioned sampan off the starboard side. Seven gun and grenade-wielding sailors crowd atop the vessel, spraying bullets in all directions. One year later, Man’s Epic showcased a Green Beret assaulting a Vietcong-infested tunnel. The American is armed to the nines, firing a rifle while grenades, a pistol, dynamite, and a bayonet all are strapped to his body. Dressed in their recognizable black pajamas, the insurgents clearly are taken by surprise, their faces full of terror. In all these depictions, the Americans unmistakably are on the offensive. These are brave men, each continuing the heroic traditions of their World War II predecessors.112

It’s likely that few, if any, of these artists had any intimate knowledge of US military operations in South Vietnam, yet they were the ones helping translate a foreign war to young readers back home. Writers followed suit. In All Man, a CIA agent goes undercover as a communist sympathizer to learn about North Vietnamese “guerrilla operations,” author Magnin Tobar clearly conflating conventional NVA forces with the southern Vietcong. The agent’s cover story has him vacationing in Hanoi, where he meets two Russian women whom he quickly seduces. They turn out to be double agents themselves, and all three bring out vital microfilm that deals a heavy blow to the communist regime. The fantasy seems all the more absurd given the story’s October 1966 publication date. By then, North Vietnam likely would not have topped many Americans’ tourist attraction spots, even if the vacationers were sympathetic to Hanoi’s plight. That the American charms two Russian “lovelies” and spends several “highly sensual – and acrobatic – hours” with them only adds to the outlandishness.113

As they interpreted the war in such fantastical ways, pulp artists and writers ultimately concocted a Vietnam that bore little resemblance to the real world. The pulps’ depiction of Vietnamese culture, geography, politics, and combat all drifted farther away from what the GIs themselves were experiencing. In fact, these fabricated representations began to form even before American combat troops arrived. In early 1962, Man’s Illustrated ran a piece noting how the NLF was having little trouble enlisting soldiers because each recruit rated three nights in a “local joy house” as part of his basic training. (Of course, readers were not told how South Vietnamese women felt about these transactions.)114 The following year, Man’s World noted that “among some Vietnamese tribes it’s considered putrid manners if you sleep with a girl without slapping her mother in the mouth first.” By 1966, Male was suggesting the United States “go after the Viet Cong with witchcraft” and “make use of the well-known superstitions of the Viets.” Thus, whether it be advocating for voodoo or for physical violence against Vietnamese mothers, the pulps were constructing a base of knowledge that left longtime readers wildly unprepared for their military tours in South Vietnam.115

One US foreign service officer, Gary Larsen, recalled the outcomes of this ignorance, which he believed led to arrogance. Larsen spoke fluent Vietnamese and argued that when Americans were unaware of the consequences of their presence, they proceeded “blissfully with actions based on … [a] one-dimensional view of the country and the people.”116 In the pulps, blissful heroic warriors never dealt with any aftereffects of war. Even when seriously wounded, these champions’ grit still shone through. In the same issue recommending voodoo in Vietnam, Male highlighted marine Colonel Mike Yunck, whose leg was amputated at a Da Nang hospital after his HU-1B helicopter had been hit with .50 caliber machine gun fire. This “courageous fighter,” though, was learning how to fly again, despite “the loss of one crummy leg.” To Male, Yunck was “still the Marines’ top ace.”117

The reality of such injuries often resulted in far less uplifting stories. Ron Kovic’s searing memoir Born on the Fourth of July offers a prime example of how wounded veterans struggled to maintain their sense of dignity after serious injury. After being paralyzed from the chest down in Vietnam, Kovic lands in a dreadful Bronx VA hospital. It is like “being in a prison.” When he complains to an aide that he is a veteran and deserves to be treated decently, the ward fires back “Vietnam don’t mean nothin’ to me or any of these other people. You can take your Vietnam and shove it up your ass.” The event leaves a dejected Kovic wondering what he had lost his legs for and why he and others had gone to Vietnam at all. If Born on the Fourth of July does inspire, it is because of Kovic’s colossal resiliency in the squalor of a run-down hospital, not in his glorious return to the battlefield in the manner of Colonel Yunck.118

When pulp heroes returned home, they did so not as broken warriors like Kovic but as men ready for sexual rewards and adventure. In Stag’s “Hottest Tease in Town,” an ex-Green Beret sergeant, “a year out of the jungles of Vietnam,” is enticed by the wife of the richest man in Colby. Though “civilian wear still felt strange to him,” Jim successfully meets the “challenge of passion” and has an affair with the beautiful woman. “You’re quite a lover,” she approvingly utters. By the end of the story, we find the husband has hired Jim to prove his wife is a cheat. The veteran has recorded the entire affair with a reel-to-reel tape recorder hidden in his briefcase but destroys it before heading back to the army recruiting station to reenlist. Thus, he demonstrates both his potent sexuality and, supposedly, his moral superiority over the unfaithful woman.119

In another tale from Stag, a marine corporal wounded at Khe Sanh returns home after promising a buddy, killed in the same action, that he would check on his wife. When Richard arrives in San Francisco, he meets Judy Prideaux, a “gleaming blond beauty.” Soon after, they begin dating, and one evening Judy is accosted by two men on Hyde Street attempting to steal her purse. Despite a bum arm, Richard fends off the assailants before being hit from behind by a thug wearing brass knuckles. Not surprisingly, the marine is rewarded sexually for his knightly valor and spends the next five days in Judy’s bed. They ultimately part because she is unwilling to marry, though Richard is “half relieved” to be free of any obligations. Only later does he find that Judy has wed a marine lieutenant on his way to Vietnam.120