Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Conventions

- Abbreviations

- Map

- Introduction

- 1 Inheritance and Education, 1513–1582

- 2 Three Feuds and Jacobean Politics, 1582–1595

- 3 Service to the State, 1595–1623

- 4 Defending the Borders of the Earldom, 1595–1623

- 5 Family Strategies and Crises, 1595–1623

- 6 Lordship and the Reformed Kirk, 1560–1623

- 7 Economic Activities, 1581–1623

- 8 Marischal College, 1593–1623

- Conclusion

- Appendices: Genealogies

- Bibliography

- Index

- St Andrew Studies in Scottish History

6 - Lordship and the Reformed Kirk, 1560–1623

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 13 April 2019

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Conventions

- Abbreviations

- Map

- Introduction

- 1 Inheritance and Education, 1513–1582

- 2 Three Feuds and Jacobean Politics, 1582–1595

- 3 Service to the State, 1595–1623

- 4 Defending the Borders of the Earldom, 1595–1623

- 5 Family Strategies and Crises, 1595–1623

- 6 Lordship and the Reformed Kirk, 1560–1623

- 7 Economic Activities, 1581–1623

- 8 Marischal College, 1593–1623

- Conclusion

- Appendices: Genealogies

- Bibliography

- Index

- St Andrew Studies in Scottish History

Summary

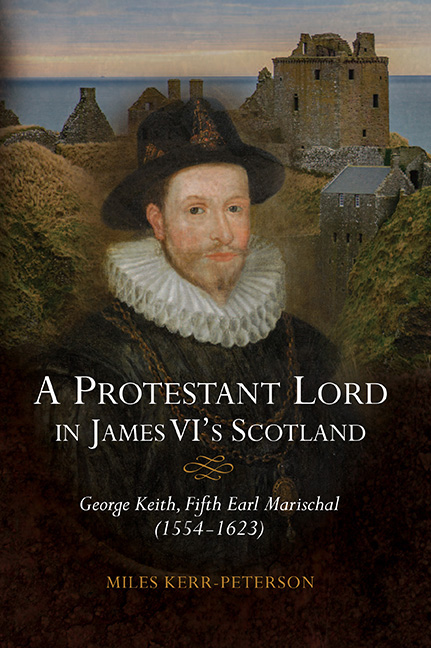

Of the ample collection of tapestries recorded within Dunnottar Castle in 1612, the only ones to be described in any detail are a group of six depicting the story of Samson. As the only pictorial and narrative set, this was the most prestigious that the family owned. The sheer cost involved in commissioning such pieces meant that the subject matter was never chosen lightly; patrons displayed figures and concepts with which they desired to be associated. From all the historic, legendary and classical stories, the Keiths chose the biblical story of Samson, suggesting that the earls were keen to foster a religious identity. William, the fourth earl, was especially noted for his devotion, having been an early convert in the 1540s. Few could doubt the zeal he expressed in his speech at the Reformation Parliament:

It is long since I had some favour to the truthe; but praised be God, I am this day fullie resolved … I cannot but hold it the verie truthe of God, and the contrarie to be deceavable doctrine. Therefore, so farre as in me lyeth, I approve the one, and damne the other.

William's surviving letters show the religious concern of a very devout man, often invoking the Holy Spirit and frequently thanking, praising or praying to God, to an extent that surpasses the letters of his close family members. The English described him as ‘very religious’. George, the fifth earl, was likewise consistently described by English commentators as ‘well affected in religion’ and Lord Hundson even remarked during the regime of the earl of Arran in 1584: ‘and for the Erle Marshall, he ys the only nobell mane that ys too be accowntyd of too stande faste for matters of relygyon’. The minister to the French-speaking Calvinist community in London, Jean Castol, recommended Marischal to the earl's old tutor, Theodore Beza, as the subject of the dedication of his next book in 1583, saying Marischal was the most appropriate choice, for his piety, reliability and great reputation among those of good breeding. The two Earls Marischal were clearly committed and recognised Protestants.

For a man consistently described as a sound Protestant, Earl George is largely absent from the works of contemporary Kirk historians, merely being mentioned in passing a handful of times.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- A Protestant Lord in James VI's ScotlandGeorge Keith, Fifth Earl Marischal (1554–1623), pp. 117 - 150Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2019