A majority of Canadians hold some form of private health care insurance, most commonly obtained as an employment benefit. Private insurance accounts for around 13% of spending on health and its financing role is essentially limited to complementary coverage for services not covered by public insurance programmes. Private supplementary insurance for services covered by the public insurance system effectively does not exist in Canada (the exception is a negligible role in the Province of Québec). This limited role for private insurance in health care reflects the core policy vision for health care financing in Canada, which emphasizes equal access to medically necessary health care, especially physician and hospital services. Compared with many other countries, Canada’s private health insurance market is relatively uncomplicated, viewed in terms of either the products offered or the regulations imposed. Although Canadians regularly debate the relative split between public and private finance overall, and a small set of advocates have persistently pressed for a greater role for private insurance, private insurance has not figured prominently in Canada’s health care policy debates, which since the late 1960s have focused on the publicly funded health care system.

Three Canadian health care policy challenges, however, are drawing the role of private health insurance into the centre of policy debate. The first was the emergence in the mid-1990s of long waiting times for some common, high-profile services such as orthopaedic surgery, eye surgery, diagnostic imaging and cancer treatments. These waiting times have fuelled advocates for parallel private financing alongside public insurance and for loosening restrictions on supplementary private insurance. Such advocates were emboldened by a landmark ruling of the Supreme Court of Canada in 2005 (Chaoulli v. Government of Québec) that, in the presence of excessive waiting times in the public system, Québec’s statute prohibiting private insurance for publicly insured services violated Québec’s Charter of Rights. Though the ruling applied only to Québec, the judgement galvanized those advocating for a fundamental change in the role of private insurance in Canadian health care. Similar legal challenges to provincial restrictions on supplementary private insurance are making their way through the courts in Alberta, British Columbia and Ontario (Reference MertlMertl, 2016; McCreith v. Ontario, 2007; Murray v. Alberta, 2007; Reference CohnCohn, 2015; Reference Thomas and FloodThomas & Flood, 2015).Footnote 1

The second element drawing private insurance into the centre of policy debate is the growing importance of pharmaceuticals in the modern pantheon of medically necessary therapies. Prescription drugs are excluded from the core services covered by Canadian Medicare, so the majority of pharmaceutical costs are privately financed. Many Canadians, however, are either uninsured or underinsured for prescription drugs (Canadian Institute for Health Information 2015). This has prompted many to call for an expansion of public financing for prescription drugs [National Forum on Health, 1997; Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada, 2002; Senate of Canada, 2002; Advisory Panel on Healthcare Innovation, 2015; Reference MorganMorgan et al., 2015]. Some proposals call for full public coverage that would supplant the large role of private insurance in this sector; others call for various types of public–private partnerships to ensure universal coverage. All of them bring to the fore the question of the desired role for private insurance in this important and expensive sector of health care.

Finally, policy-makers and system analysts increasingly appreciate the interactions between the publicly and privately financed components of the overall health care system. Unequal access to privately insured services can lead to unequal access to and use of publicly insured services. Reference StabileStabile (2001), Reference Allin and HurleyAllin & Hurley (2009) and Reference Devlin, Sarma and ZhangDevlin, Sarma & Zhang (2011), for instance, found that other things being equal, those with private drug insurance used more publicly financed physician services (an effect unlikely to be driven by selection). This type of evidence prompts hard questions regarding the scope of policies necessary to achieve objectives set for the publicly financed health system.

This chapter reviews the role of private health insurance in Canada. It begins with a brief overview of the Canadian health care system; considers the historical path that led to the current role for private health insurance; examines the current market for private health insurance; assesses the evidence for how private insurance contributes to or detracts from health financing goals; and offers some concluding comments on private health insurance in Canada.

Canada’s health care system

Canada is a federation, so the design of the Canadian health care system derives from the allocation of responsibilities in Canada’s constitutional documents between the federal government and the provincial governments. The British North America Act of 1867 and the 1982 Constitution assign responsibility for health care to provincial governments and provide the federal government with extensive revenue-raising power. Consequently, Canada’s health care system comprises 13 distinct provincial/territorialFootnote 2 health care systems. Each provincial system, however, conforms to national standards embodied in the 1984 Canada Health Act, which the federal government enforces through a system of conditional federal transfers (the Canada Health Transfer) to the provinces (Box 4.1).

By international standards, Canada spends an above-average amount on health care. Per person spending on health in 2016 was Can$5900, which placed it 12th among OECD countries behind the United States, Switzerland, the Netherlands and Norway, among others (OECD, 2017).Footnote 3 Health care spending in Canada represented 10.6% of gross domestic product in 2016 (OECD, 2017). After slowing in the mid-1990s during a period of unprecedented fiscal restraint in the public sector, real (inflation-adjusted) total health care spending rose at an annual rate of 4.6% between 1996 and 2008 (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2010) but has decreased by an average of 0.6% per year between 2010 and 2015 (Canadian Institute for Health Information 2015).

Box 4.1 Canada Health Act national standards for full federal transfer

To be eligible for the full federal transfer, a provincial public insurance plan must conform to each of the following five Canada Health Act principles:

Accessibility: the plan must not impede, either directly or indirectly, whether by charges made to insured persons or otherwise, reasonable access to insured health services.

Comprehensiveness: the plan must cover medically necessary physician and hospital services, including surgical–dental services that require a hospital setting.a

Universality: the plan must cover all provincial residents on uniform terms and conditions.b

Portability: the plan must not impose a minimum period of residence in excess of 3 months for new residents, it must cover its own residents when temporarily in another province (or country in the case of non-elective services) and during the waiting period in another province for residents who have moved permanently.

Public administration: the provincial plan must be administered and operated on a non-profit basis by a public authority.

Notes:

a Insured services exclude services covered by the workers’ compensation system, which are financed through employer contributions to the workers’ compensation fund.

b The insured population excludes certain subgroups such as members of the military, Royal Canadian Mounted Police, prisoners and aboriginals, who are covered by the federal government.

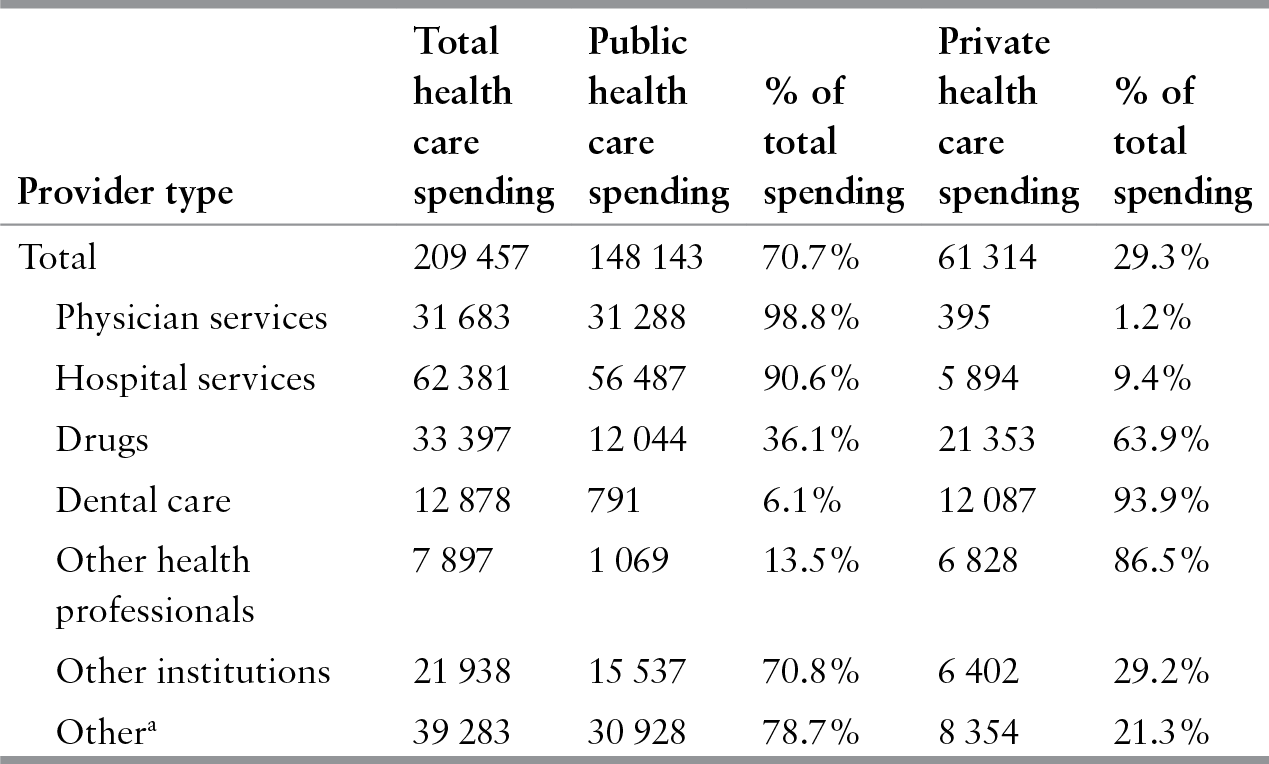

Health care in Canada is predominantly publicly financed (Table 4.1). In 2014, 71% of health care was financed publicly, a level that is a bit lower than the peak of 77% in 1976 but which has remained relatively constant since the late 1990s. The Canada Health Act’s focus on physician and hospital services, however, leads to a unique pattern of public financing across health care sectors. Public financing for physician and hospital services, commonly referred to as Canada’s Medicare programme, constituted 99% and 91% of spending in these sectors in 2013. Outside these two sectors the role of public insurance is markedly smaller and more variable. Public finance is next most important for other institutions, such as long-term care facilities, and least important for dental care (for which the only universally publicly insured dental care is inpatient oral surgery and the public sector finances about 6% of all services). In between is the drug sector, for which the public sector financed 36% of all drugs (and 43% of prescription drugs) in 2013. De facto, therefore, Canada’s “single-payer, universal” system of public finance accurately applies only to physician and hospital services. Unsurprisingly, Canada has one of the lowest levels of public spending on pharmaceuticals among OECD countries (OECD, 2017).

Table 4.1 Health care spending in Canada by source of funds, 2013

| Provider type | Total health care spending | Public health care spending | % of total spending | Private health care spending | % of total spending |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 209 457 | 148 143 | 70.7% | 61 314 | 29.3% |

| Physician services | 31 683 | 31 288 | 98.8% | 395 | 1.2% |

| Hospital services | 62 381 | 56 487 | 90.6% | 5 894 | 9.4% |

| Drugs | 33 397 | 12 044 | 36.1% | 21 353 | 63.9% |

| Dental care | 12 878 | 791 | 6.1% | 12 087 | 93.9% |

| Other health professionals | 7 897 | 1 069 | 13.5% | 6 828 | 86.5% |

| Other institutions | 21 938 | 15 537 | 70.8% | 6 402 | 29.2% |

| Othera | 39 283 | 30 928 | 78.7% | 8 354 | 21.3% |

Notes: All figures in Can$ millions; figures may not add due to rounding.

a For example, expenditure on capital, public health, administration, health research.

The public insurance programmes are financed primarily through personal income and consumption taxes levied by both the federal and provincial governments. Two provinces – British Columbia and Ontario – retain national health care premiums for the core Medicare services. The premiums vary according to income in both of these provinces and in addition by household composition in British Columbia; none of the provinces risk-adjust the premiums. An individual cannot be denied service for failure to pay the premium, so they are, de facto, simply taxes.Footnote 4 Three provinces (Québec, Alberta and Nova Scotia) charge premiums to some beneficiaries of their public drug insurance programmes. The premiums depend on income and beneficiary status: Québec and Nova Scotia exempt those on social assistance; Alberta exempts seniors and those on social assistance (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2012). Four provinces (Newfoundland, Québec, Ontario and Manitoba) collect a health-specific payroll tax (rates up to 4% depending on the size of a firm’s payroll), but in general, neither local taxes nor payroll taxes contribute meaningfully to health care finance.

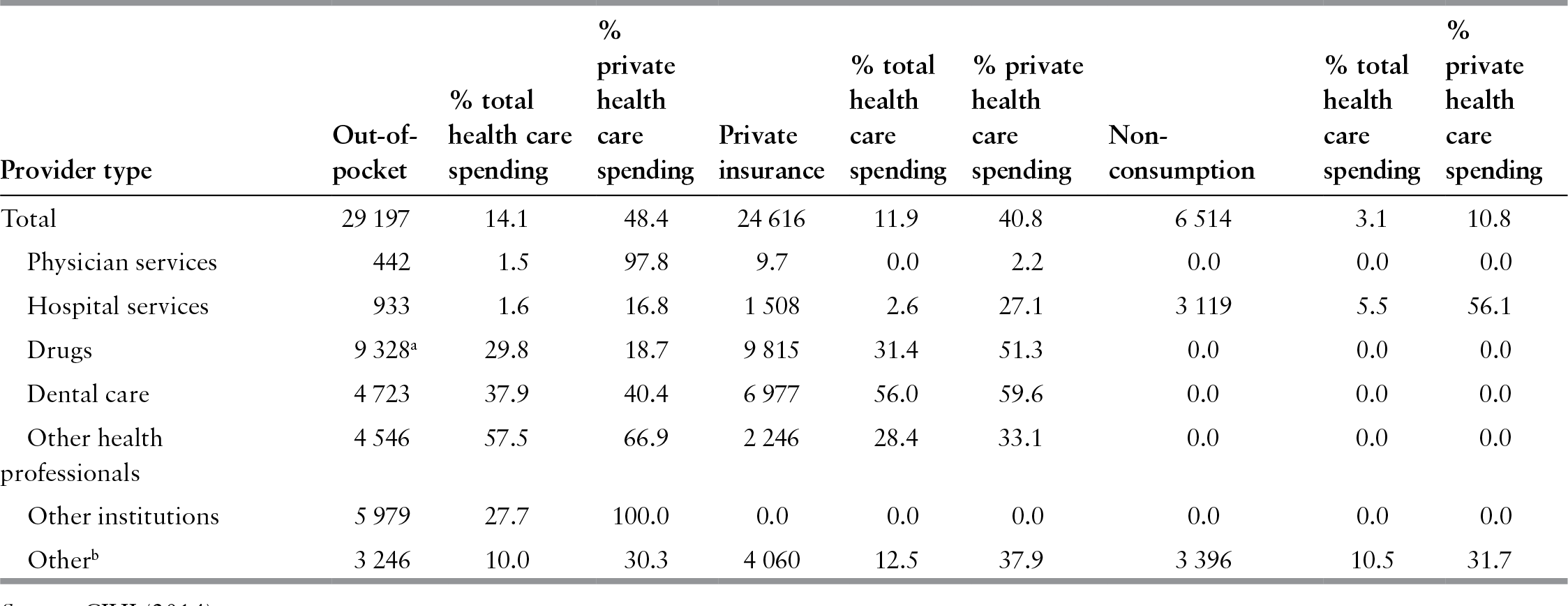

Private finance encompasses a mixture of direct, out-of-pocket payments for care (48%), private insurance coverage (41%) and “nonconsumption” spending (11%), which includes non-patient revenue to hospitals (ancillary operations, donations and investment income), spending on research and capital expenditure in the private sector (Table 4.2).Footnote 5 Overall, private out-of-pocket spending is a larger source of finance than is private insurance, though again, this varies by sector. Private insurance plays an important role only outside the physician and hospital sectors. In 2012, for instance, although 12% of health care was financed through private insurance, this proportion ranged from a low of effectively 0% for physician services and 2.6% for hospital care to over 56% for dental services (Table 4.2). Dental care is the only sector for which private insurance finances a majority of care. Private insurance is next most important for drugs, for which it finances about 30% of spending. Insurance for dental care and drugs are the largest sources of revenue for the private insurance industry: private insurers derived 40% of premium revenue from drug insurance and 28% from dental insurance in 2012 (Canadian Institute for Health Information 2014).

Table 4.2 Private health spending in Canada, 2012

| Provider type | Out-of-pocket | % total health care spending | % private health care spending | Private insurance | % total health care spending | % private health care spending | Nonconsumption | % total health care spending | % private health care spending |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 29 197 | 14.1 | 48.4 | 24 616 | 11.9 | 40.8 | 6 514 | 3.1 | 10.8 |

| Physician services | 442 | 1.5 | 97.8 | 9.7 | 0.0 | 2.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Hospital services | 933 | 1.6 | 16.8 | 1 508 | 2.6 | 27.1 | 3 119 | 5.5 | 56.1 |

| Drugs | 9 328a | 29.8 | 18.7 | 9 815 | 31.4 | 51.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Dental care | 4 723 | 37.9 | 40.4 | 6 977 | 56.0 | 59.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Other health professionals | 4 546 | 57.5 | 66.9 | 2 246 | 28.4 | 33.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Other institutions | 5 979 | 27.7 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Otherb | 3 246 | 10.0 | 30.3 | 4 060 | 12.5 | 37.9 | 3 396 | 10.5 | 31.7 |

Notes: All figures in Can$ millions; figures may not add due to rounding.

a This includes out-of-pocket spending on both prescription drugs and over-the-counter medications. Out-of-pocket costs for prescription drugs constitute approximately 70% of this total.

b For example, expenditure on capital, public health, administration, health research, personal health supplies, and other health care goods and services.

Although most provinces decentralized governance in the 1990s, beginning in the early 2000s a number of provinces have recentralized health system governance. Regionalized health authorities generally control institutional care (acute hospital and long-term care), community care (home care services), public health and a variety of smaller programmes. In no instance does their authority extend to public, community-based drug programmes or physician services, which in all provinces are administered by the provincial ministry of health. Provincial governments allocate budget envelopes to regional health authorities based on a mixture of historical funding levels and need criteria, and each regional health authority allocates its budget among the services, programmes and providers over which it has authority. Although regional health authorities increasingly use contractual approaches in their relationships with providers of services, nowhere is the relationship between the regional authorities and providers in their region formally structured as a purchaser–provider split designed to foster an internal market.

Hospitals in Canada are most commonly funded through annual global budgets. The basis for the global budget varies across the provinces and regions. In most settings a hospital’s budget includes a large purely historical component, but hospital funding methods increasingly incorporate factors based on a hospital’s case-mix adjusted volume. Physician services are funded predominantly by fee-for-service, though the role of alternative payment methods – including capitation, salary, programmatic funding and incentive-based payments – has been increasing, especially within the primary care sector. Long-term care is funded either through global budgets for public facilities or, for private facilities, through per diem public subsidies to facilities based, in many cases, on standardized assessments of the severity of the condition of residents in a facility (Reference MarchildonMarchildon, 2013).

All provinces offer a public drug-benefit plan for community-based drug purchases.Footnote 6 Public drug coverage is concentrated among older people and individuals on social assistance, but all residents are potentially eligible for coverage in British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario and Québec, albeit with greater cost-sharing for working-age and/or high-income individuals (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2012). British Columbia and Manitoba changed from age-based coverage criteria to income-based criteria in 2003 and 1996, respectively. In 1996–1997, Québec introduced a novel public and private financing arrangement for its universal drug coverage scheme, Canada’s only explicit public–private insurance partnership (see Box 4.2). Public expenditure on drugs varies across the provinces, ranging from a low of 33–37% of prescription drug expenses in Atlantic provinces (Newfoundland, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick) to nearly 50% in Saskatchewan (Canadian Institute for Health Information 2015).

Box 4.2 Québec’s mixed public–private universal drug plan

In 1997, the province of Québec implemented a compulsory prescription drug insurance plan for all its residents designed on a social insurance basis. Universal coverage is achieved through a coordinated mixture of private insurance plans, most often available through employment, and a public plan, administered by the Régie de l’assurance maladie du Québec. The Régie was established in 1969 with the objective to develop the public health insurance plan in the province of Québec. All residents under the age of 65 who are eligible for a private plan must obtain at least its prescription drug coverage component for themselves, their spouse and children, provided their spouse and children are not already covered by another private plan. Insurance plans provided by employers may have eligibility requirements (for example, exclude part-time, temporary or contractual employees) and may not provide coverage to all employees. However, risk selection based on age, sex or health status is not permitted. The premium is negotiated between the policy-holder (that is, typically a group plan sponsor such as an employer, union or association) and the insurer, but is paid by the persons insured.a The Régie sets the maximum annual individual contribution to the cost of such insurance (Can$1046 effective from July 2016 to June 2017). The Régie, in collaboration with Revenu Québec, conducts eligibility verifications to ensure that those who have access to a private plan do not obtain coverage from the public plan. When turning 65, those who have access to a private plan with basic prescription drug coverage can choose to retain their private plan coverage or join the public plan.

The public prescription drug insurance plan provides coverage to persons aged 65 and over, social assistance recipients, persons who do not have access to a private plan, and children of persons covered by the public plan. The public plan charges a premium collected through income tax; the premium is capped at Can$660 per adult per year (effective from July 2016 to June 2017), depending on net family income.b The public plan covers prescription drugs listed on a formulary published by the Régie. Individuals must register for the public plan. Failure to register does not exempt individuals from paying the premium and payment of the premium is not a substitute for registration. Individuals who fail to register receive no drug coverage. See Reference PomeyPomey et al. (2007) for additional details on the introduction and design of Québec’s programme.

Notes:

a As of 1 January 2007, an employer is obliged to deduct premiums for private prescription drug insurance from employee remuneration unless the employee is covered under another private insurance plan.

b The following individuals are exempt from paying the premium: children of insured persons, social assistance recipients, low-income seniors, seniors who have a private prescription drug plan whose benefits exceed those contained in the public plan. (Seniors who have private coverage more limited than that of the public plan must pay the premium.)

Canadian health care, like health care systems around the world, faces a number of difficult challenges. Some of the prominent current policy challenges include long waiting times for selected services, shortages and a maldistribution of some health professionals, an outmoded primary care delivery system dominated by physicians in solo or small group practice, a drug sector with ever-rising costs and increasing access problems for some Canadians, and dated information systems that impede information sharing and the creation of an electronic health record.

The development of private health insurance in Canada

Canada’s current financing and delivery arrangements largely derive from a series of policy decisions made in the 1950s and 1960s, which themselves reflected an assessment at that time of the contribution that private insurance could make to achieving key policy goals. The 1930s witnessed both the emergence of private health care insurance as a marketed commodity and some of the first initiatives to provide public insurance. A survey conducted by the Canadian Medical Association in 1934 identified 27 hospital prepayment plans operating in six provinces (Reference 139HallHall, 1964). Under prepayment plans (akin to modern health maintenance organizations in the United States), the hospital was both the insurer and provider: an individual paid a fixed premium to a hospital in return for the provision of specified services should they be needed during the period covered. The first “Blue Cross” prepaid plan for hospital services was established in Manitoba in 1937 (Reference 139HallHall, 1964).Footnote 7 This was quickly followed by Blue Cross plans in Ontario in 1941, Québec in 1942, the Maritimes and British Columbia in 1943 and Alberta Blue Cross in 1948. Profession-sponsored (and controlled) prepayment plans for medical services developed in parallel with the spread of hospital insurance. The first such plan was offered in Toronto in 1937, followed by plans in Windsor, Ontario and Regina, Saskatchewan in 1939, and then a series of plans across Canada during the 1940s. The Medical Services Association of British Columbia, established in 1940, was the first province-wide medical plan. Life insurance companies and casualty insurance companies (which insure all risks other than life) also began offering various types of health care and disability insurance during this period, with life insurance companies tending to focus on the group market while casualty insurers concentrated on the individual market. Finally, insurance cooperatives played an important role, especially in the early part of this period and in the west of Canada.

During the same period, calls for public insurance programmes grew as well, especially in the western provinces that were particularly hard hit by the depression. These initiatives often found considerable support within the medical profession, in part for purely economic reasons: many patients could not pay for care privately, making it difficult for a physician to maintain a practice. The public efforts included municipally based initiatives, such as the municipal doctor programme and the creation of hospital districts to finance and oversee hospitals, and provincial initiatives to introduce public insurance. Both Alberta and British Columbia passed public health insurance plans in the 1930s, though neither plan was implemented. National health care insurance was a central element in the federal government’s vision for post-war social programmes. The federal plan, however, was scuttled in the breakdown of the federal–provincial Dominion talks in 1945, leaving provinces to act alone. In 1946 Saskatchewan became the first province to implement a provincial hospital insurance plan. Saskatchewan was followed in 1949 by British Columbia and Alberta.

By the 1950s voluntary insurance had made considerable in-roads into the Canadian middle class. This had a number of important impacts vis-à-vis public and private financing. It reduced the pressure for large-scale public action because a substantial proportion of the population had access to at least some insurance. It also weakened physician support for public insurance, especially public medical insurance. The medical profession strongly advocated for private plans, particularly physician-sponsored plans, which retained control and power for the profession. These developments altered the nature of the debate regarding public health insurance. Rather than public insurance, many analysts now advocated limiting the public role to public subsidy for low-income individuals that would enable them to purchase private insurance. The success of both the voluntary private insurance plans and the few then-existing provincial public plans demonstrated the soundness of such insurance plans and the value people placed on insurance. The gaps in private coverage (even in urban Ontario) suggested, however, that private insurance could never provide universal coverage, and the increasing demands on provincial and local resources and on hospitals themselves provided an opportunity for the federal government to act on its national vision. The result was the Hospital Insurance and Diagnostic Services Act of 1957. This legislation provided universal public insurance for inpatient hospital services financed through a combination of provincial revenue (raised through a variety of specific instruments across the provinces) and matching federal grants. The provincial hospital insurance plans supplanted private insurance for medically necessary inpatient services. Hospital benefits offered by private insurance shrank to supplementary, mostly nonmedical, services associated with a hospitalization (for example, room upgrade from ward to semi-private).

The huge success of public hospital insurance, the growing importance to Canadians of access to a wide range of health care services and, ironically, concern by the medical profession over growing support for public universal insurance (rather than public subsidy to private insurance) prompted the establishment in 1961 of the Royal Commission on Health Services led by Justice Emmett Hall (hereafter the “Hall Commission”). The Hall Commission was given a broad mandate with respect to the planning, delivery and financing of health care in Canada. The starting point for the Commission’s assessment of private and public insurance options was the principle that all Canadians should have access to necessary health care, a principle agreed to by all major stakeholders such as the medical profession, private insurers, business and consumer groups. Major stakeholders, however, differed on the best policies for achieving this objective. The medical profession, private insurers and private industry argued that this could best be achieved through private insurance supplemented with public subsidies to those who otherwise could not afford such insurance; others argued for a system of universal public insurance. The Commission judged three issues as central to the policy choice: the ability of voluntary insurance to provide universal comprehensive insurance; the costs associated with means-testing to determine eligibility for a public subsidy; and the legitimacy of compelling individuals to participate in such a public insurance scheme. In the end, the Commission recommended, in addition to the then-existing system of universal hospital insurance, a system of universal public insurance for medical services, dental services, drugs and home care. This recommendation was based on the judgement that a system of private insurance, even accompanied by public subsidies, could not achieve universal coverage and access;Footnote 8 that the number of persons requiring subsidy under a private system would be large and that means-testing would require a large, expensive and unnecessary administrative infrastructure; and that compulsory membership of a universal public plan would not violate fundamental rights. The Commission viewed universal public insurance as a less costly way to achieve universal coverage than a system based on private insurance (Reference 139HallHall, 1964).Footnote 9

Based on the Commission’s recommendations, the federal government passed the Medical Care Act of 1966 which, like the 1957 Hospital Insurance and Diagnostic Services Act, provided for a system of matching federal grants to provincial medical care insurance plans that met defined criteria of universality, comprehensiveness, public administration and portability. By 1972, all provinces had public plans that complied with these principles. Because of fiscal concerns, the legislation excluded drugs, dental care and home care services. The 1957 Hospital Insurance and Diagnostic Services Act and the 1966 Medical Care Act, later consolidated in the 1984 Canada Health Act, defined the basic roles of public and private insurance in Canada that exist to this day.

The current market for private health insurance

Who has private health insurance coverage?

No single source summarizes the number and characteristics of Canadians who hold private health insurance. Figures regarding various aspects of private insurance coverage demonstrate that a large majority of Canadians hold some type of private health insurance. The majority of those covered obtain insurance as a benefit of employment (of themselves, a spouse or a parent). The data are most comprehensive for private drug coverage. Self-reported data from the 2014 Canadian Community Health Survey indicate, for instance, that 54% of Ontarians held employer-based prescription drug coverage and 5% held individually purchased drug insurance (Statistics Reference CanadaCanada, 2014).Footnote 10 These self-reported data suggest somewhat lower coverage than other sources. The Canadian Life and Health Insurance Association (CLHIA), for example, estimates that about 24 million Canadians (or about two thirds) were covered by private extended health care insurance (that is, insurance schemes that reimburse expenses such as prescription drugs, dental, hospital and medical expenses, not covered by provincial government plans) in 2015 (CLHIA, 2016).

In 2005, among those who were employed, the rates of coverage for health-related benefits varied substantially according to the sector of employment, workplace size (employers with over 500 employees were three times more likely to offer such benefits than those with fewer than 20), part-time/full-time status (full-time employees were three times more likely to receive benefits), earnings (those earning Can $20 per hour or more were 2.9 times more likely to receive benefits than those earning less than Can$12 per hour) and union status (unionized employees were about 30% more likely to receive benefits than non-unionized employees) (Statistics Reference CanadaCanada, 2008).

Insurance organizations

Three types of insurers in Canada sell private health care insurance: for-profit health and life insurance companies, non-profit insurance organizations whose primary business is health coverage, and for-profit property and casualty insurers whose primary business is not health-related. The market is dominated by for-profit life and health insurers, which nationally account for approximately 80% of the private health insurance market; non-profit health insurers rank next; property and casualty insurers constitute less than 5% of the market.Footnote 11 The relative market shares of these different types of insurance organizations vary by province, and the non-profit insurers in particular have a strong regional structure. The most recent available data indicate that in the early 2000s just over 80% of insurers operated in more than one province and were subject to both federal and provincial regulations; the remainder operated in a single province and were subject to provincial regulation only (Reference Vella and FaubertVella & Faubert, 2001).

The primary source of information on private insurers comes from an annual factbook published by an industry trade organization, the CLHIA. Although the CLHIA membership is made up of life and health insurance companies, and does not include property and casualty insurers, some of the data reported in the annual CLHIA factbook includes property and casualty insurers. Consequently, the data reported represents over 99% of the for-profit insurance organizations (I. Klatt, personal communication).Footnote 12

The CLHIA reported that in 2014, 127 insurance organizations sold health insurance products in Canada (CLHIA, 2015). Nearly all were incorporated in Canada (93) or the United States (23). The sector has been subject to a number of mergers and acquisitions since the mid-1990s, which has increased market concentration in the industry. Among the 127 insurance organizations, 64 life and health insurance companies and 16 not-for-profit health care benefit providers sold over 99% of all private complementary health care and disability insurance products and 47 property and casualty companies sold the balance. The vast majority of the 64 life and health insurance companies were incorporated as publicly traded stock companies; the remaining were mutual companies formally owned by the policy-holders. Since 1997 many insurance organizations have changed status from mutual companies to for-profit stock companies traded on stock exchanges. This transformation was allowed by regulatory changes in 1997 and 1998 and has been motivated by the companies’ desire to gain access to equity capital (Reference Vella and FaubertVella & Faubert, 2001). The non-profit sector has only a few firms that operate nationally, and is dominated by regional Blue Cross organizations, which are associated with the Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association in the United States (Blue Reference CrossCross, 2016).Footnote 13

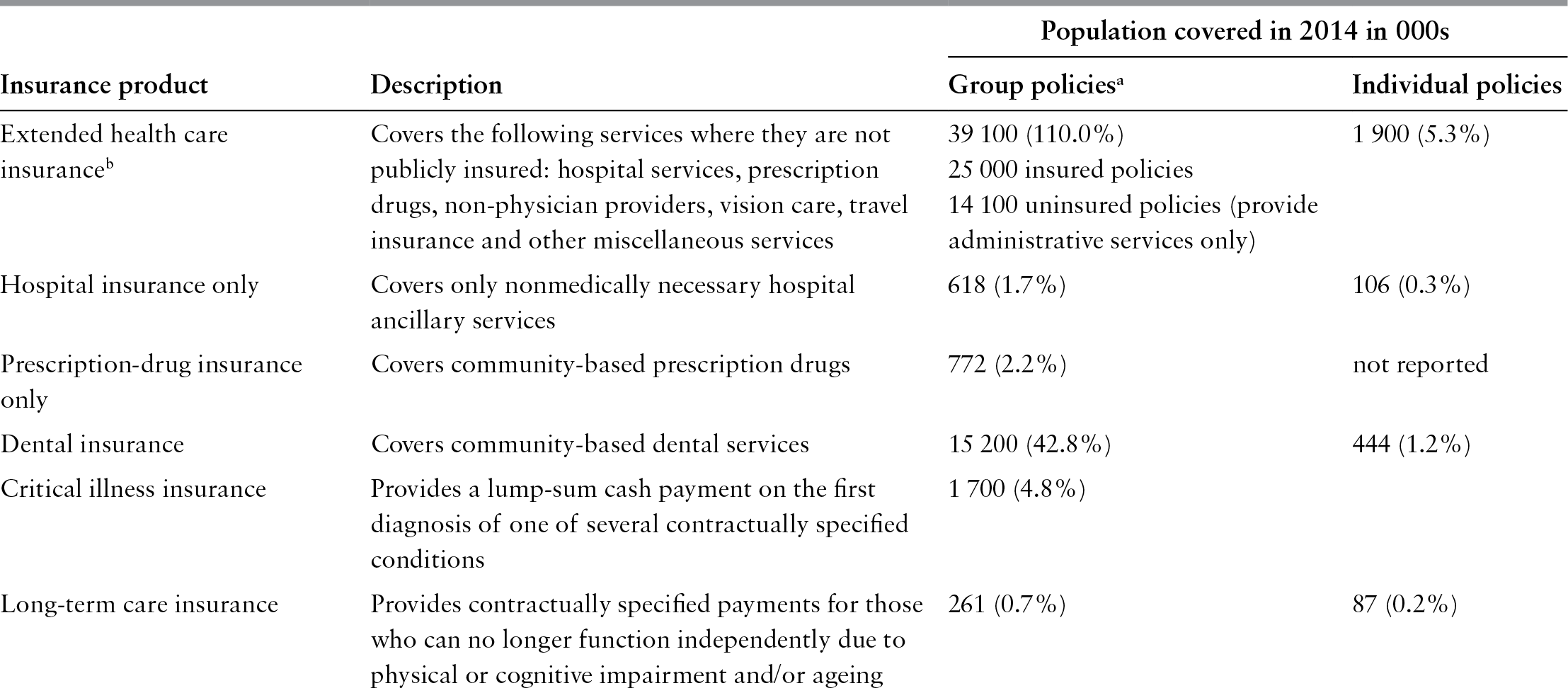

Insurance products

Private insurers in Canada offer nine basic types of health-related insurance (Table 4.3). Extended health care plans insure a range of hospital and other health care expenses not covered by a provincial public insurance plan, including hospital amenities, prescription drugs, non-physician providers, vision care, medical devices, travel insurance and ambulance service. Policies normally include deductibles and coinsurance provisions as well as annual and/or lifetime maxima for specific types of services. The details vary by plan, and cost-sharing is in general increasing, but cost-sharing provisions are usually relatively minor for hospital services and prescription drugs. Private prescription drug coverage, for example, typically has an annual individual or family deductible of Can$25 per individual or Can$50 per family; requires 20% cost-sharing above the deductible; and might have an out-of-pocket payment limit of approximately Can$2000. The coverage may be more limited for other services in the plan, depending on the coverage purchased by the plan sponsor. Coverage for nonphysician services such as physiotherapy, chiropractic care or counselling may be limited to a specific number of visits annually or a maximum dollar amount (for example, Can$500–600), depending on the plan sponsor’s selection (I. Klatt, personal communication).

Table 4.3 Private health insurance products in Reference CanadaCanada, 2014

| Insurance product | Description | Population covered in 2014 in 000s | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group policiesa | Individual policies | ||

| Extended health care insuranceb | Covers the following services where they are not publicly insured: hospital services, prescription drugs, non-physician providers, vision care, travel insurance and other miscellaneous services |

| 1 900 (5.3%) |

| Hospital insurance only | Covers only nonmedically necessary hospital ancillary services | 618 (1.7%) | 106 (0.3%) |

| Prescription-drug insurance only | Covers community-based prescription drugs | 772 (2.2%) | not reported |

| Dental insurance | Covers community-based dental services | 15 200 (42.8%) | 444 (1.2%) |

| Critical illness insurance | Provides a lump-sum cash payment on the first diagnosis of one of several contractually specified conditions | 1 700 (4.8%) | |

| Long-term care insurance | Provides contractually specified payments for those who can no longer function independently due to physical or cognitive impairment and/or ageing | 261 (0.7%) | 87 (0.2%) |

| Long-term disability insurance | Provides income replacement at a contractually specified rate in the event of long-term disability |

| 970 (2.7%) |

| Short-term disability insurance | Provides income replacement at a contractually specified rate in the event of short-term disability |

| not reported |

| Accidental death and dismemberment insurance | Provides contractually specified cash payment in the event of death or loss of one or more body parts as a result of an accident | 18 800 (52.9%) | 2 200 (6.2%) |

| Travel insurance only | Covers the costs of emergency medical services (that are not publicly insured) required when travelling outside Canada |

| |

Notes: Figures in parentheses indicate the number covered as a proportion of the Canadian population.

a Includes an unknown amount of double-counting when two (or more) members of a household each obtain coverage for themselves and their dependants from different group policies. Hence, the figures overestimate the extent of private insurance coverage. The CLHIA estimates that adjusting for double-counting reduces the number of Canadians covered through these plans to about 24 million for private complementary health benefits and 20 million for dental care benefits.

b The set of included services varies across policies. The defining feature is that a single policy covers multiple types of services that are not publicly insured. All policies include hospital services; most include prescription drugs; the variation is largest for other services.

c Most group coverage is obtained as part of extended health policies. Most individual policies are sold at time of travel on a trip-by-trip basis. 9.9 million individual policies sold in 2009.

The market for extended health care insurance is heavily dominated by group contracts provided by employers to employees or purchased through professional orders, associations and unions for their members. Group contracts dominate for the usual reasons: for workers, the value of such an employment benefit is tax exempt (more on this below); for others, access to a group policy through an association (for example, a farm cooperative) offers substantially lower premiums than those available in the individual market; and, for insurers, group contracts incur lower overhead costs and reduce the potential for adverse selection. In 2015, revenue from group contracts constituted 90% of total premium revenue (CLHIA, 2016).

Most complementary hospital and prescription drugs are obtained through extended health care benefits, so the markets are considerably smaller for policies that provide only complementary hospital coverage or only prescription drug coverage (I. Klatt, personal communication; CLHIA, 2015, 2016). Dental plans cover community-based dental services only. Dental coverage is normally obtained through stand-alone policies and is not included in an extended health care policy. Dental policies also normally include modest deductibles and cost-sharing in the range of 20% above the deductible.

Disability income insurance plans insure against lost income if one is unable to work due to accident or ill health.Footnote 14 Both accidental death and dismemberment insurance and critical illness insurance are indemnity policies that pay a pre-specified amount of money when a specified health-related event occurs. Accidental death and dismemberment insurance pays the predetermined amount, which varies according to the injury, to those who die or are dismembered in an accident. Critical illness insurance provides a predetermined payment if any of a pre-specified set of critical illnesses occur, such as heart attack, stroke and cancer. In recent years it has been one of the fastest-growing types of private insurance in Canada because it avoids restrictions on private insurance for publicly insured services (it does not cover any services per se) while providing resources to purchase private care if necessary in the event of a serious illness. Nearly all of its coverage is through individual polices, although it is increasingly included in extended health care policies provided to employees by employers. The number of Canadians covered under critical illness plans on either a group or an individual basis increased from 1.1 million to 1.7 million between 2009 and 2014 (CLHIA, 2010, 2015).

From the early 2000s, long-term care insurance has emerged as a new private insurance product in Canada but the market for such a product remains underdeveloped (Reference ColomboColombo et al., 2011; SCOR, 2003). Fewer than 350 000 Canadians were covered under long-term care insurance plans in 2014 (a lower number than in 2010) (CLHIA, 2014, 2015).

Travel insurance covers costs associated with emergency medical services required while travelling outside Canada.Footnote 15 It is most commonly obtained as part of an extended health care policy, but can also be purchased on a trip-by-trip basis from travel-related agencies.

In addition to standard group insurance plans, some employers offer a type of defined contribution plan called Health Spending Accounts. Such accounts can either substitute for or complement standard insurance benefits depending on the overall set of benefits provided by an employer. Under a Health Spending Accounts plan, each year an employer makes a predetermined contribution to an employee’s health spending account (the amount must be specified before the start of the year). These funds are then available to an employee to fund eligible health-related services, defined as the services that would qualify for the medical expense tax credit in the tax code. Unspent balances at the end of the first year can be rolled over into the second year, but at the end of the second year after which a contribution is made, tax regulations require that the employee forfeit unspent balances (which revert to the employer). The employer’s contributions are tax deductible for the employer and non-taxable to the employee. The market for Health Spending Accounts is very small.

Finally, private insurers in Canada also sell administrative services to governments and to private sector organizations that self-insure their members. Medavie Blue Cross, the Atlantic Canada Blue Cross organization, for example, provides administrative services to a number of public insurance programmes.Footnote 16 It also offers, on contract with the Ministry of Health, nongroup, individual complementary health insurance plans (Alberta Blue Cross and Alberta Health and Wellness, 2007). Plans that private insurers administer on behalf of private companies are called “uninsured plans”, for which employers accept the financial risk but contract out the administration of the benefits. At the end of 2014 such plans covered more than 14 million individuals (5.7 million workers and 8.4 million dependants) with extended health care insurance, 13 million (5.5 million workers and 5.1 million dependants) with dental care coverage, and 2.4 million workers with long-term and 970 000 workers with short-term disability income insurance. Premium income from uninsured plans constituted 41% of all premium income for group insurance plans (CLHIA, 2016).

Private health insurance regulation

Private health care insurers in Canada are subject to two types of government regulation: regulation intended to ensure the financial solvency of insurers and regulation of the types of policies offered by private insurers and the terms and conditions under which the policies are sold.

Financial regulation

Financial regulation is conducted by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions at the federal level and, in the province of Québec, by the Financial Markets Authority (Autorité des marchés financiers). The Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions and the Financial Markets Authority conduct regular inspections and insurers are required to submit annual returns to document solvency. All insurers (for-profit and non-profit) are required by federal government regulations to be a member of Assuris, an industry-funded non-profit organization that protects policy-holders in the event that an insurer becomes insolvent. Assuris guarantees policy-holders recovery of 100% of the promised benefits for health expenses below Can$60 000 and 85% of health expenses above Can$60 000.

Regulation of insurance products

Provincial governments regulate the market for private health insurance both directly, by regulating the provision of private health insurance, and indirectly, by regulating the provision of private health care services. Canadian regulation of the design of insurance products, their pricing and their sale are for two reasons relatively weak by international standards. First, as has been emphasized, private insurance has for 50 years played a minor role in health care financing, and no role for core hospital and physician services. Second, most people obtain private insurance through group contracts in which they face little or no choice. Hence, the private insurance sector in Canada has not been subject to the kinds of policy focus found in settings in which people rely on private health insurance as a major source of financial protection and people must obtain such insurance through individual policies. Undoubtedly some negative effects of market failure, discrimination, strategic policy design and other phenomena exist in some Canadian markets, but to date they have been rare enough or small enough to escape policy concern.

The most important product regulation is that which prohibits private insurers from covering publicly insured medical and hospital services. Five provinces (British Columbia, Alberta, Manitoba, Ontario and Prince Edward Island) prohibit private insurers from covering publicly insured physician and hospital services. In the province of Québec, private insurers are only permitted to cover publicly insured services for very few selected services, including total hip or knee replacements and cataract extractions with intraocular lens implantations.Footnote 17 Provincial governments have indirectly limited the growth of private insurance through regulation of physicians and the fees they charge for private services, which has made the provision of privately financed services also covered by the public plan financially non-lucrative. For publicly insured physician services, most provinces require that a physician either fully opt into the provincial plan or fully opt out; a physician cannot choose to charge privately for some patients but publicly for others.Footnote 18

A physician would therefore have to support an entire practice through private, out-of-pocket payment by patients, which is not feasible for most physicians. In addition, many provinces also regulate the fees that can be charged by physicians who opt out of the public plan (Reference Flood and ArchibaldFlood & Archibald, 2001). Manitoba, Ontario and Nova Scotia prohibit opted-out physicians from charging private fees greater than the fees paid by the public plan. Other provinces permit opted-out physicians to charge fees higher than those in the public plan; however, all but Newfoundland and Prince Edward Island prohibit such patients from receiving any public subsidy. Newfoundland is the only province that currently allows private health insurance coverage for publicly insured physician and hospital services, allows opted-out physicians to charge more than the public fee and allows patients to receive public coverage for a service even when the fees charged are higher than those of the public plan. In such cases, the physician must bill the patient directly and the patient must subsequently obtain reimbursement from the province as is applicable. As noted above, few physicians have opted out of the public plan: in 2013 no physicians were opted out in seven of the ten provinces – Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland – while two were opted out in British Columbia and 24 in Ontario (Health Reference CanadaCanada, 2015). In 2016, 339 physicians were opted out in Québec (71 specialists and 261 general practitioners) (RAMQ, 2016).

Regulation of premiums and the terms of sale

Neither the federal government nor any provincial government regulates the premiums that private insurers can charge for health insurance.

Tax regulations

A number of regulations within the federal and provincial tax codes support private health insurance in Canada. Currently, both the federal government and all provincial governments allow firms to deduct the cost of health benefits provided to employees. The federal government and all provinces except Québec exclude the value of such benefits from the employee’s taxable income. The exclusion of health insurance benefits from taxable income dates from 1948, and the current value of this tax expenditure is estimated to be Can$2.5 billion in 2013 for the federal government alone (Department of Finance, 2016). Public spending on health in Canada was estimated to be Can$145 billion in 2013 (Canadian Institute for Health Information 2015), suggesting that combined federal and provincial tax expenditures associated with private health insurance constitute about 3% of public health care spending in Canada. A number of provincial governments have attempted to remove this tax provision, and the federal government last debated removing it in 1994. Only the government of Québec succeeded in doing so: since 1993 Québec has included the value of employer-provided health insurance in taxable income.

Both the federal government and provincial governments also provide a set of health-related tax credits. The two most important are the medical expense tax credit (value of approximately Can$1.3 billion in 2013) and the disability tax credit (value of Can$770 million in 2013) (Department of Finance, 2016). The medical expense tax credit allows individuals to claim a tax credit for eligible medical expenses greater than 3% of their income, or Can$2228 (in 2015), whichever is greater.Footnote 19 Premiums paid by individuals for private insurance qualify as a medical expense under this provision.Footnote 20 This provision affects private insurance in three ways: it reduces the net cost of out-of-pocket payment, dampening demand for private insurance; it subsidizes insurance by making an insurance premium an eligible expense; and the set of services eligible for the tax credit also defines the services eligible to be paid from a health spending account. The disability tax credit applies to individuals with a severe and prolonged mental or physical impairment. In 2016 it equalled Can$7889 for qualifying individuals.

Assessment of market performance

Because private health insurance plays a relatively limited, complementary role in financing health care in Canada, with the exception of a few sectors, its overall effects on market performance are correspondingly small. As has been emphasized, by policy design, private insurance plays no meaningful role for medically necessary physician and hospital services; its role in these sectors is limited to inpatient amenities and a small set of non-publicly covered services. It has also played no meaningful role for long-term care and home care services because market penetration for insurance products is so low.

Private insurance has had the largest impact on system performance through its operations in the drug and dental sectors. But even here its impact on overall performance has historically been limited by the small size of these sectors and, in the case of dental care, the absence of a strong substitute or complementary relationship between dental services and other health care services, and a lack of public concern regarding access to dental care beyond a small set of specific services such as serious oral surgery or specific groups such as children. Drug financing, however, emerged as a central policy concern during the 1990s as drugs became both a growing component of overall health expenditure and an essential therapeutic agent for an expanding set of medical conditions. In 1996–1997 Québec established its universal drug coverage through its mixed public–private approach; in 1997 the National Forum on Health recommended national universal publicly financed drug coverage (National Forum on Health, 1997), and in 2002 both the Romanow and the Kirby Commissions recommended publicly financed national catastrophic drug coverage (Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada, 2002; Senate of Canada, 2002). More recently, calls for a national pharmacare have intensified (Reference MorganMorgan et al., 2015).

The limited role of private insurance in financing health care means that the private insurance sector in Canada has been little studied.Footnote 21 Policy and research attention have focused overwhelmingly for the last 35 years on the publicly financed system. We know surprisingly little about either the operation of the private insurance sector or the effects of its activities. This is changing because the role of private insurance is central to some of the current policy challenges facing Canadian health care, but there remains a relative dearth of publicly available data and information upon which to base studying the private insurance sector.

Financial protection

Private insurance in Canada contributes in only a minor way to universal protection against financial costs. Public insurance fully covers medically necessary physician and hospital services. Private insurance coverage is a trivial source of finance for long-term care and home care. Extended health care insurance generally covers at least some non-physician providers, but such coverage is often restricted to a small number of visits annually or to low limits on maximum annual coverage. Indeed, the policies are structured so as to provide minimal financial protection: they cover occasional use of such providers for routine services while doing little to help those who may need regular, ongoing, more intensive care. Although private insurance finances a majority of community-based dental care, such services are generally not a large source of financial risk. The bulk of insurance payments cover routine visits and minor procedures that are both modest and quite predictable. Private insurance contributes the most toward financial protection in the drug sector, where it covers a large number of individuals not covered by public insurance programmes. Drug spending is becoming an increasing source of financial risk to individuals as the use of drugs in treatment expands and the costs of new drugs marches ever upward. Private drug insurance policies generally include small deductibles and cost-sharing provisions (though they are increasing), maximum out-of-pocket spending limits and relatively high maximum coverage limits, so the plans provide important financial protection.

Equity in financing

Canadian health policy is strongly committed to equity in health care financing. Policy documents explicitly interpret equity in finance as horizontal equity, which requires equal contributions by those with equal ability to pay, and vertical equity, which requires contributions to be directly related to ability to pay. Policy statements are less clear as to whether vertical equity implies progressivity in finance, whereby contributions increase as a proportion of income. The Romanow Commission offered one of the few explicit judgements on this in positing that vertical equity implies progressivity (Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada, 2002).

Only a limited number of studies have empirically assessed equity in health care financing in Canada. Fewer still have examined private finance. Nonetheless, findings across studies are generally consistent and it is possible to draw a few conclusions from existing evidence.

Public finance to support health care appears to be essentially proportional or perhaps mildly progressive. The two largest sources of public revenue are income and consumption taxes, which have counteracting effects: income taxes are progressive but consumption taxes are regressive. Reference McGrailMcGrail (2007) estimated that public financing for physician and hospital services in British Columbia in both 1992 and 2002 was effectively proportional (Kakwani indices of progressivity of 0.021 and 0.026, respectively). Reference HanleyHanley et al. (2007) found that public finance for prescription drugs in British Columbia over the period 2000–2005 was proportional (annual Kakwani indices of –0.002 to –0.008 over the period). Reference MustardMustard et al. (1998) similarly found that public finance in Manitoba in both 1986 and 1994 was essentially proportional. Reference 141SmytheSmythe (2002), however, found public financing in Alberta to be more strongly progressive. Provincial public contributions as a proportion of income, for example, rose from 4% to 8% between the lowest and highest income deciles.

Two studies (Reference MustardMustard et al., 1998; Reference McGrailMcGrail, 2007) conducted net fiscal incidence analyses for the health sector that considered both tax payments to finance health care and benefits received in the form of publicly financed health care services. Utilization of health care services is highly regressive – the value of services received by low-income individuals is a much higher proportion of their income than it is for high-income individuals (both because absolute levels of utilization by low-income individuals are greater than for high-income individuals and because any given amount of utilization is a larger share of income for a low-income individual than for a high-income individual). Hence, both found that, because contributions are roughly proportional to income but use is highly regressive, the incidence of net benefits is highly progressive: on net, for low-income groups in Canada the value of publicly financed services received far exceeds their contribution, so the health care system redistributes economic resources from high-income groups to low-income groups.

Studies of the incidence of private insurance financing are more limited. Private insurance coverage is strongly related to income, causing contributions for private insurance to increase with income. Reference SmytheSmythe (2001), for instance, estimated that in 1994 only 4% of households with incomes less than Can$5000 had access to employer-sponsored private insurance; the proportion rose to 54% for those with incomes between Can$20 000 and Can$30 000, and was over 90% for households with incomes greater than Can$60 000. Reference Bhatti, Rana and GrootendorstBhatti, Rana & Grootendorst (2007) found a substantial positive income gradient with respect to holding private dental insurance. Controlling for a range of demographic and health factors, the probability that those with an income of over Can$80 000 held private dental insurance was 34 percentage points greater than those with an income of less than Can$15 000. Reference HanleyHanley et al. (2007), however, estimated that prescription drug financing through private insurance in British Columbia was mildly regressive (Kakwani index –0.10) in both 2000 and 2005. Reference 141SmytheSmythe (2002) estimated that private financing (including both out-of-pocket and private insurance payments) in Alberta was regressive (Kakwani index –0.12). We are not aware of any net incidence studies for private health insurance in Canada.

The exclusion of the value of employer-provided health insurance from employees’ taxable income generates substantial tax expenditures. This tax exclusion reduces a person’s income tax payment in proportion to their marginal tax rate; for middle- and low-income individuals its exclusion from income reduces payroll taxes for the Canadian Pension Plan and Employment Insurance; and for low-income workers it increases eligibility for rebates of the General Services Tax. Reference SmytheSmythe (2001) estimated that the value of these tax expenditures in 1994 was less than Can$0.50 per household for households with incomes below Can$5000 and Can$250 for households with incomes over Can$100 000. Hence, the tax treatment of private insurance generates a strongly regressive element in health care finance.

Reference CorscaddenCorscadden et al. (2014) examined how health care affected the distribution of income by estimating the tax contributions and the value of benefits received from physician services, drugs and hospital services over a person’s lifetime and found that benefits received from publicly funded health care in Canada reduce the income gap between the highest and lowest income groups by about 16%.

Equity of utilization

Both federal and provincial governments in Canada identify allocation according to need as the explicit distributional health policy goal for health care services. The primary, though not exclusive, policy designed to achieve this goal is removal of financial barriers at the point of service, especially for physician and hospital services. Equity of utilization of health care has been extensively studied in Canada, reflecting both a strong concern for equity and the availability of population health survey data upon which to assess equity. Here we emphasize recent work that employs the concentration index approach pioneered by the ECuity group (Reference Wagstaff, van Doorslaer, Culyer and NewhouseWagstaff & van Doorslaer, 2000) to estimate income-related equity of utilization. Most of this work has focused on physician and hospital services, although studies of other sectors are increasingly available. A general finding consistent with the international literature is that greater reliance on private finance, including private insurance, is associated with less equity in the utilization of health care services.

Overall, the pattern of findings suggests that, controlling for need, use of general practitioner (GP) services is not strongly related to income in Canada. A first generation of studies that tested for an income gradient using regression methods consistently found that, controlling for need, the coefficient on income was not statistically significant (Reference Birch and EylesBirch & Eyles, 1992; Reference Birch, Eyles and NewboldBirch, Eyles & Newbold, 1993). More recent studies based on concentration indices obtain a mixture of point estimates that, although statistically different from zero (due in part to large sample sizes), are small in absolute magnitude, suggesting little income-related inequity. Reference van Doorslaer and Masseriavan Doorslaer et al. (2005), Reference Jimenez-Rubio, Smith and van DoorslaerJimenez-Rubio, Smith & van Doorslaer (2007) and Reference Marsden and XuMarsden & Xu (2009), for instance, obtain slightly pro-poor horizontal equity indices, while Reference AllinAllin (2008) obtains a slightly pro-rich horizontal equity index. Studies consistently found offsetting effects for the likelihood of any visit and the conditional number of visits: the likelihood of any visit to a GP was generally estimated to be pro-rich, but conditional on seeing a GP, the number of visits was distributed pro-poor (that is, low-income individuals had more visits than high-income individuals even after controlling for need).

In contrast, controlling for need, analyses consistently found a pro-rich income-related gradient in the use of specialist services in Canada (Reference Alter, Austin and TuAlter, Austin & Tu, 1999; Reference van Doorslaer and Masseriavan Doorslaer et al., 2005; Reference AlterAlter et al., 2006; Reference van Doorslaer, Lu and Jonssonvan Doorslaer, 2007; Reference AllinAllin, 2008; Reference WangGrignon, Hurley & Wang, 2015).

The income-related gradient is modest by international standards, but it nonetheless clearly exists. We do not have a good understanding of what causes this gradient.

Hospital services are distributed in a strongly pro-poor manner even after controlling for need (Reference Jimenez-Rubio, Smith and van DoorslaerJimenez-Rubio, Smith & van Doorslaer, 2007; Reference van Doorslaer, Lu and Jonssonvan Doorslaer, 2007; Reference AllinAllin, 2008). By international standards, the gradient is large. Once again, we do not have a good understanding of what drives this income-related gradient.

Sectors that rely heavily on private finance, including private insurance, tend to exhibit strong income-related gradients in use. Dental care, which is almost entirely privately financed, exhibits the largest income-related gradient (Reference van Doorslaer, Lu and Jonssonvan Doorslaer, 2007; Reference GrignonGrignon et al., 2010; Reference WangGrignon, Hurley & Wang, 2015). Access to drugs has been less studied, but Reference ZhongZhong (2008) found a large impact of drug financing arrangements in Ontario on income-related equity: income-related use of drugs was pro-poor among older people, who are covered by the public insurance programme, but pro-rich among working-age individuals, who must finance drugs privately; furthermore, the introduction of coinsurance provisions in the public programme was associated with a reduction in equity among older people. Reference Allin and LaporteAllin & Laporte (2011) found that in the Ontario public drug benefit programme for seniors, after adjusting for need, the mean number of drugs claimed was modestly pro-poor and there was little difference in spending on medications between income groups. Reference KratzerKratzer et al. (2015) found that Ontarians with chronic conditions who held private drug insurance were more likely to use prescription drugs than those without.

Rewarding good-quality care and providing incentives for efficiency in the organization and delivery of services

To the best of our knowledge, the private insurance industry has undertaken almost no efforts to improve the quality and efficiency of health care services in Canada. On the contrary, there is some evidence that the private health insurance industry may have become more inefficient. Reference Law, Kratzer and DhallaLaw, Kratzer & Dhalla (2014) found that the percentage of private health insurance premiums paid out as benefits had decreased markedly in the 1990s and 2000s, leading to a gap between premiums collected and benefits paid of Can$6.8 billion in 2011. The private insurance industry continues to function largely as bill payers. Increasing costs for privately insured services (especially drug costs) is a growing concern for employers, but the most prevalent response has been demand-side cost-sharing. In addition, employers increasingly rely on benefit managers to advise them on how to control such costs.

Administrative costs

Private insurers in Canada incur greater administrative costs than do the public insurers. Reference Woolhandler, Campbell and HimmelsteinWoolhandler, Campbell & Himmelstein (2003) estimated that administrative overhead costs for Canadian private insurers were 13.2% of expenditures whereas those of the public system were 1.3%. Indeed, administrative costs for Canadian private insurers slightly exceeded those of US private insurers.

Interactions between the publicly and privately financed health systems

Wherever private insurance and public insurance systems coexist, they inevitably interact. Policy debate has centred mostly on interactions when public and private insurance cover the same services and providers are able to work in both systems. Such a situation can lead to privileged access to those with private insurance, providers playing each system to their advantage, and potentially longer waiting times in the public system as the private system draws scarce resources away.

By prohibiting or making unprofitable private insurance (and private finance more generally) for publicly insured physician and hospital services Canada has successfully minimized such interactions. Canada, however, faces increasing pressure to relax its insurance prohibitions. As noted earlier, in June 2005 the Supreme Court ruled that, in the presence of “unreasonable” waiting times (though it did not define “unreasonable”), Québec’s prohibition on private insurance for publicly insured services violated the Québec Charter of Rights and Freedoms. The long-term implications of this decision are not clear. The ruling applied only to Québec. The government of Québec responded by passing legislation that guarantees maximum waiting times for three procedures that in recent years have had long waiting times: hip replacement, knee replacement and cataract removal; enables the creation of private, for-profit clinics; and allows private insurance for only the three above-noted procedures when they are provided by a physician who has opted out of the public plan (Québec National Reference AssemblyAssembly, 2006); this list was subsequently expanded to include approximately 50 procedures (Reference ContandriopoulosContandriopoulos et al., 2012; Government of Québec, 2016). Similar lawsuits are under way in three other provinces, raising the chances of additional decisions against laws prohibiting private insurance and, eventually, a ruling with respect to the Canadian Charter of Rights with national implications (Allen v. Alberta, 2014; Reference CohnCohn, 2015; Reference Thomas and FloodThomas & Flood, 2015; Reference MertlMertl, 2016). However, the effects on private insurance and private finance remain uncertain even if such bans are struck down nationally because complementary regulations that inhibit the development of private finance would remain in force (Reference BoychukBoychuk, 2006). Reference CohnCohn (2010, Reference Cohn2015) notes that 5 and 10 years after the Chaoulli decision, very few insurance schemes sought to offer coverage for publicly insured services to Canadians. Reference CohnCohn (2010) was able to document only two small insurance schemes, one of which was more properly characterized as a medical tourism scheme. Similarly, Reference CohnCohn (2015) was only able to document a few very small niche operators that offered medical tourism coverage. Of note, none of the major insurance companies have sought to capitalize on the Chaoulli v. Québec decision (Reference CohnCohn, 2015).

The growth of the market for privately financed nonmedically necessary services (paid mostly out of pocket) that fall outside the Canada Health Act increasingly generates interactions with the public system. Such services include traditional cosmetic procedures and an increasing array of “lifestyle” health care services that do not address an underlying health problem but which must be provided by a health professional. Such services constitute one of the fastest-growing components of health care spending. The expansion of such services does not raise equity concerns – they are nonmedically necessary services – but it does generate all of the other potentially negative effects of supplementary private insurance. Specifically, the expansion of such services draws health care inputs (for example, provider time and effort) away from the public system and bids up their prices, compromising the ability of the public system to ensure access to medically necessary services.

The growth of this market in nonmedically necessary services also has more subtle effects. By regulating a physician’s ability to opt out and charge fees greater than the public fee, Canada has successfully inhibited the growth of privately financed markets. However, these regulations do not apply to the services, which are not publicly insured. Furthermore, because the financial and physical capital invested to provide such services can often be used to provide both nonmedically necessary and medically necessary publicly insured services, the growth of this sector can make private practice for those doctors who have opted out of the public system increasingly viable through the provision of a mixture of privately financed medically necessary and nonmedically necessary services; and further develop the privately financed sector as this entrepreneurial capital seeks out profitable uses. These forces are still relatively minor in Canada outside a small number of cities, but they are growing.

The heavy reliance on private finance, and private insurance in particular, in the drug sector creates at least three types of policy-relevant interactions between the public and private systems. The first two arise from complementarities between privately financed drugs and publicly insured medical services. Obtaining a prescription drug requires a medical visit and, for many individuals, the expected outcome of a medical visit is a drug prescription. Hence, when a person is ill, if the expected outcome of the visit is a prescription for a drug that must be paid privately, the full cost of the visit is not zero, but rather the free medical visit plus the cost of the prescribed drug. Inability to purchase the resulting prescription may inhibit individuals from making some physician visits. Hence, private finance for drugs distorts the use of publicly financed physician visits toward those with greater ability to pay, either because of higher income or private insurance coverage. Indeed, Reference StabileStabile (2001) and Reference Devlin, Sarma and ZhangDevlin, Sarma & Zhang (2011) found that those who have drug insurance were more likely to visit a physician than were those who did not have insurance, while Reference Allin, Law and LaporteAllin, Law & Laporte (2013) found that Ontario seniors with private prescription drug insurance used more publicly funded medications and incurred more in costs to the public programme (about 16%). Furthermore, Reference Allin and HurleyAllin & Hurley (2009) found that private insurance contributed to income-related inequity in visits to general/family practitioners in Canada. Reference WangWang et al. (2015) evaluated the effects of Québec’s mandatory, universal prescription insurance on drug use, and GP and specialist visits, hospitalizations, and health outcomes, and found that it increased prescription use and GP visits, especially among the previously uninsured and those with chronic conditions, while having little effect on specialist visits and hospitalizations. The estimated spillover effect on the number of GP visits was about 10%.The second interaction rooted in complementarities arises in the cancer sector. The publicly funded cancer system in Ontario (as in other provinces) has chosen not to cover some of the new, very expensive cancer drugs that are judged not to be cost-effective. Because they have been approved for sale, individuals are able to purchase these drugs privately. Such intravenous drugs, however, must be infused in suitable facilities by trained professionals. Such settings are generally found only in the publicly funded hospital facilities that treat cancer patients. In Ontario, for instance, a number of publicly funded hospitals administer privately purchased intravenous cancer drugs and infuse those drugs for private payment, guided by the following recommendations of a Provincial Working Group: (i) the practice does not contravene the Canada Health Act or relevant provincial legislation because the drugs are not publicly funded; (ii) hospitals should administer only drugs for which Cancer Care Ontario’s Program in Evidence-Based Care has not issued a recommendation against the use of the drug for the specific indication; (iii) all drugs administered should be prepared by the hospital pharmacy – a hospital is not to infuse a drug purchased elsewhere and brought to the infusion clinic; (iv) patients are to be charged for the costs of the drug only, with no mark-up; and (v) patients are to be charged a fixed infusion fee to cover non-drug costs and, for certain radioimmunotherapies that are more complex to administer, hospitals can charge an additional fixed fee per patient (Provincial Working Group on the Delivery of Oncology Medications for Private Payment in Ontario Hospitals 2006). The working group also recommended that privately funded treatment should not displace publicly funded patients from treatment, though it offered no guidance on policies and practices to ensure this. The recommendations were first implemented at Ontario’s 16 regional cancer centres, but ultimately the decision to provide such privately financed services and the precise policies followed rests with individual hospitals.Footnote 22

The third interaction arises when public and private insurers structure benefit plans strategically in an attempt to shift costs on to the other. The Nova Scotia government, for instance, has explicitly made the public Pharmacare programme second payer for seniors who have private drug coverage through their previous employer’s retirement benefits. It also requires companies operating in both Nova Scotia and other jurisdictions to offer such retiree benefits to Nova Scotia employees if they are offered to employees in other locations. In Québec, where residents aged 65 or over are automatically covered by the provincial drug insurance plans, businesses have increased the premium they charge retirees for drug coverage to encourage retirees to rely on the public plan rather than the company-provided retirement benefit.

Lastly, arguments about the unsustainability of publicly financed health care in Canada are often based on the observation that health care costs have been rising “too fast” to be sustainable. Ironically, however, one of the fastest-growing components of health care for the last number of years has been drugs, a sector in which private finance and private insurance play a dominant role. Hence, the fast rate of growth for privately financed services can undermine confidence in the long-run sustainability of the overall system, including the public system.

Discussion