The Portuguese Restoration of 1640 and Its Global Visualization

The Portuguese Restoration of 1640 and Its Global Visualization Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Signs, Miracles, and Conspiratorial Images

- 2 The Lisbon Miracle of the Crucifix (1 December 1640)

- 3 The New King’s Oath (15 December 1640)

- 4 Acclamations

- 5 Lisbon

- 6 Images in Diplomatic Service

- 7 The Imaculada as Portugal’s Patroness

- 8 The Funeral Apparatus of John IV (November 1656)

- 9 The Drawings in the Treatise of António de São Thiago (Goa 1659)

- 10 Ivory Good Shepherds as Visualizations of the Portuguese Restoration

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index

Introduction

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 13 February 2024

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Signs, Miracles, and Conspiratorial Images

- 2 The Lisbon Miracle of the Crucifix (1 December 1640)

- 3 The New King’s Oath (15 December 1640)

- 4 Acclamations

- 5 Lisbon

- 6 Images in Diplomatic Service

- 7 The Imaculada as Portugal’s Patroness

- 8 The Funeral Apparatus of John IV (November 1656)

- 9 The Drawings in the Treatise of António de São Thiago (Goa 1659)

- 10 Ivory Good Shepherds as Visualizations of the Portuguese Restoration

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index

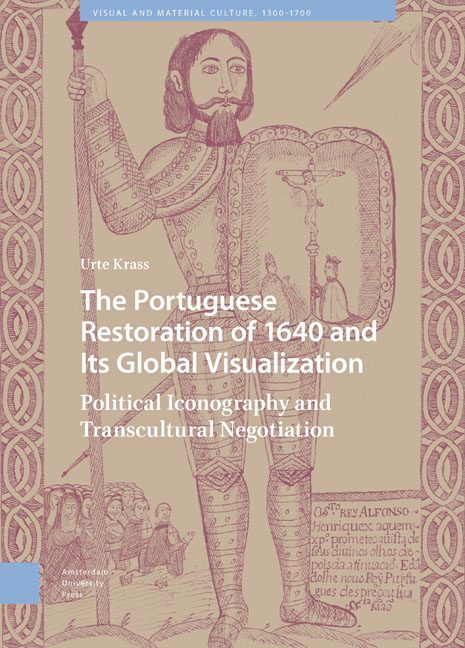

Summary

Abstract: The introduction sets up the framework for the following chapters. It outlines the circumstances that led to the uprising of 1 December 1640 in Lisbon and presents the book's fundamental questions and premises related to visual anthropology. These include the meanings and terminologies of Baroque visualizations as well as transcontinental communication processes in the period under investigation. The book is situated in the methodological field of political iconography and anchored in transcultural art history. Theories of “iconic knowledge,” “image action,” and the “decentralization of Europe” are introduced as heuristic tools for the book. The introduction also discusses the status of heterogeneous and multidirectionally moving images as either products of cultural translation, “wandering” or “circulating” images, or even “image vehicles” (Aby Warburg).

Keywords: political iconography, transcultural art history, visual culture, decentering of Europe, cultural translation, circulation

Why do human beings produce images? And what do these images actually accomplish? Now as before, art historians and a range of theorists work under the weight of these basic questions. In this book, I hope to illuminate the complex, dynamic processes that were foundational for the global movement of images at a specific time. My historical focus will be on the 1640 Lisbon coup d’état and its visualization in Portugal and its overseas colonial territories. What image worlds emerged in connection with this political caesura? How were these worlds intertwined? What agency could they develop?

On 1 December 1640, a group of Portuguese higher nobility (fidalgos, the “sons of someone,” fils d’algo) put an end to Spain's rule of Portugal, which had begun in 1580. In the early morning hours, we read, a group of allegedly exactly forty conspirators gathered to execute the long-planned coup. They killed and then defenestrated the hated state secretary, Miguel de Vasconcelos, imprisoned the Spanish vicereine of Portugal, Margaret of Savoy, and declared the powerful Duke John II of Braganza (1604–1656) as the new king. He entered Lisbon on 6 December, and on 15 December he was sworn in as King John IV of Portugal.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Portuguese Restoration of 1640 and Its Global VisualizationPolitical Iconography and Transcultural Negotiation, pp. 29 - 52Publisher: Amsterdam University PressPrint publication year: 2023