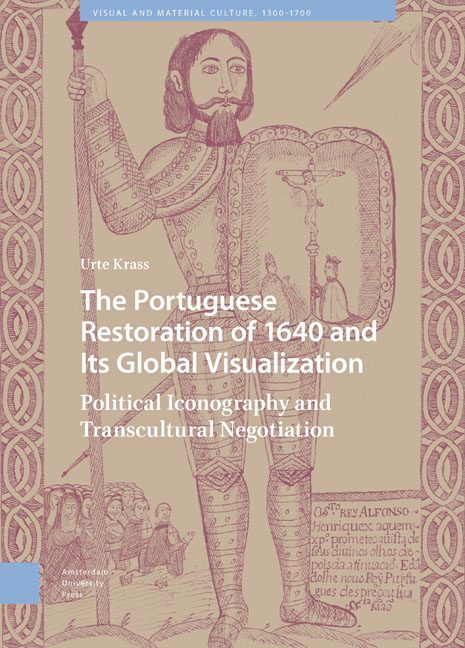

The Portuguese Restoration of 1640 and Its Global Visualization

The Portuguese Restoration of 1640 and Its Global Visualization Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Signs, Miracles, and Conspiratorial Images

- 2 The Lisbon Miracle of the Crucifix (1 December 1640)

- 3 The New King’s Oath (15 December 1640)

- 4 Acclamations

- 5 Lisbon

- 6 Images in Diplomatic Service

- 7 The Imaculada as Portugal’s Patroness

- 8 The Funeral Apparatus of John IV (November 1656)

- 9 The Drawings in the Treatise of António de São Thiago (Goa 1659)

- 10 Ivory Good Shepherds as Visualizations of the Portuguese Restoration

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index

4 - Acclamations

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 13 February 2024

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Signs, Miracles, and Conspiratorial Images

- 2 The Lisbon Miracle of the Crucifix (1 December 1640)

- 3 The New King’s Oath (15 December 1640)

- 4 Acclamations

- 5 Lisbon

- 6 Images in Diplomatic Service

- 7 The Imaculada as Portugal’s Patroness

- 8 The Funeral Apparatus of John IV (November 1656)

- 9 The Drawings in the Treatise of António de São Thiago (Goa 1659)

- 10 Ivory Good Shepherds as Visualizations of the Portuguese Restoration

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

Abstract: News of the coup d’état was systematically circulated throughout the kingdom and its overseas territories. The Portuguese Restoration became a “celebrative phenomenon.” Beginning in Coimbra, where the news of the change of power arrived on 6 December 1640, the chapter explores the subsequent stations chronologically, naming the specifics of the respective celebrations and ephemeral visualizations of the Restoration. Highly detailed reports exist on the celebrations in Cochin and Macau. After close readings of these two reports, the chapter approaches the phenomenon of ephemeral festive architectures, pageants, processions, and masquerades, employing Regis Debray's theory of médiologie to ask to what extent the mobilization of members of all social strata in processions, parades, and masquerades could lead to a lasting internalization and “transmission” of the new political situation.

Keywords: acclamations, festival culture, ephemeral art, pageants, masquerades, transmission

Initially, the Portuguese Restoration was what Paulo Varela Gomes has termed a “celebrative phenomenon.” News of the coup d’état was systematically circulated throughout the kingdom in the first December days of 1640. Portalegre and Évora were informed on the second, Elvas on the third, Coimbra on the fourth and fifth, Santarém, Leiria, and Porto on the sixth. Ceremonial acts served in the following days, weeks, and months as part of a “liturgy of legitimacy.” The celebrations taking place all over Portugal were, in turn, assiduously reported on in Lisbon. The first Cortes under the new king, held on 28 January 1641, issued an official decision to promulgate the news throughout the empire.

Coimbra (6 December 1640—8 February 1641)

While we have only sketchy information on most of the acclamation festivities, the events in Coimbra are relatively well documented. They lasted from 6 December 1640 to 8 February 1641. As soon as the news of the successful political upheaval arrived, students took up the initiative there. They carried the standard from the city hall and rode with it through the city, proclaiming the new king. Their goal was the Church of Santa Cruz: the arrival of the news coincided with the 455th anniversary of Afonso Henriques's death, an occasion that at that very same moment was being solemnly celebrated. The mass was now interrupted, the standard bearer bowed before the first king's tomb and proclaimed the new king, upon which all present fell into paroxysms of joy.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Portuguese Restoration of 1640 and Its Global VisualizationPolitical Iconography and Transcultural Negotiation, pp. 143 - 200Publisher: Amsterdam University PressPrint publication year: 2023