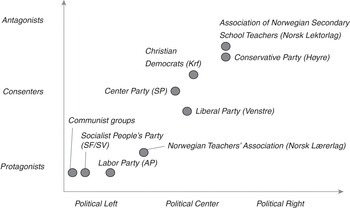

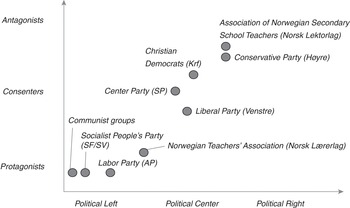

This chapter explores the comprehensive school reforms of the 1950s to 1970s and examines how such reforms were legitimized or put into question ideologically. The analysis demonstrates how actors grouped into ideological camps along a political left-right axis in both cases, into protagonists, consenters, and antagonists of these reforms. The struggles around comprehensive school reforms should therefore be seen as an ideological expression of the class cleavage. However, political parties and teachers’ organizations were not united, but most of the time divided internally into different wings that supported or opposed comprehensive schooling to different degrees. The most palpable difference between the cases is that the political right was ideologically comparatively more united in Germany, while the political left was more united in Norway. The ideological arguments that were used in debates about comprehensive schooling also differ markedly. Comparatively radical and leftist arguments became hegemonic in Norway, but not in Germany.

The Norwegian Youth School Reform

The introduction of a comprehensive lower-secondary school, the youth school, and the extension of obligatory schooling to nine years were first debated in Norway in the early 1950s. In 1954, a law on school experiments was passed unanimously. In 1959, parliament was split over the issue of whether the old school types, realskole and framhaldsskole, should be allowed to participate in experiments with nine-year obligatory schooling. The 1960s were characterized by debates about organizational differentiation. The two tracks of the youth school were replaced with a system of ability grouping and elective subjects. In 1969, the law on primary schools regularized the youth school and finalized the abolition of the old school types but did not contain specific rules for differentiation. During the 1970s it was discussed whether grades in the youth school should be abolished. After a fierce public debate, the abolition of grading in the youth school was abandoned. With the curriculum of 1974, ability grouping was given up, and from 1979 the directives of the Ministry of Education stated that permanent ability grouping was unlawful until the ninth grade. Children were now taught in mixed-ability classes (sammenholdte klasser), based on the idea of pedagogical differentiation within the classroom. In the following, this development is examined chronologically in more detail.

Experiments with the First Youth Schools and Nine-Year Obligatory Schooling

The introduction of the youth school (ungdomsskole) was first suggested in 1952 by a commission (Samordningsnemnda) that had been put in place in 1947 to discuss the internal coordination of the education system (Reference TelhaugTelhaug, 1969, 24ff). In the spring of 1954, the Ministry of Education, led by the social democrat Birger Bergersen, proposed the law on experiments in the school (lov om forsøk i skolen), which was passed after little debate in June 1954. The law did not contain any details on the future school structure. It simply opened up the possibility for experiments. It instituted the Experimental Council (Forskningsrådet), which was intended to coordinate school experiments in line with the law (Reference MediåsMediås, 2010, 43). It was stipulated that the council should inform parliament about the experiments regularly. The law gave the ministry decision-making power as far as all school experiments were concerned. Far-reaching competencies were transferred from parliament to the ministry (Reference SlagstadSlagstad, 2001, 379ff; Reference TelhaugTelhaug, 1969, 32).

Conservative Party representatives made some minor suggestions for changes, but when these failed the law was passed unanimously (Forhandlinger i Odelstinget, June 17, 1954, 173f; Forhandlinger i Lagtinget, June 22, 1954, 75ff). At the time, the Conservative Party had no clear education-political profile but was internally split. One of its leading education politicians, Erling Fredriksfryd, consented to the youth school reform. Fredriksfryd was a primary schoolteacher and a parliamentary representative of the Conservative Party from 1945 to 1965. From 1958 to 1965, he was chair of the parliamentary education committee. In 1957, he was chair of a commission within the Conservative Party that drafted the party’s education-political manifesto. The program he stood for was summarized in the Conservative Party’s electoral manifesto of 1957:

The Conservative Party wants to realize eight years of obligatory schooling for everyone as soon as possible. The organization of the school must be reorganized so that we obtain a six-year primary school and a three-year lower-secondary school. Obligatory schooling will comprise the primary school and the two first years of the lower-secondary school. The third lower-secondary school year shall be voluntary for the time being and give access to upper-secondary education [gymnas] (3-years). […] Within the new lower-secondary school, it must be possible to differentiate based on predispositions, abilities, and future choice of profession through careful tracking which does not weaken the general education an obligatory school first and foremost must preserve. […] In this way, the Conservative Party wants to actively advocate the creation of equal conditions of education for all youths, without regard to one’s place of residence and economic living conditions.

Later, Fredriksfryd published two brochures that explained the details (Reference FredriksfrydFredriksfryd, 1960, Reference Fredriksfryd1965). Notably, the lower-secondary school envisaged by Fredriksfryd was meant to replace the parallel school types of the realskole and the framhaldsskole. There was no consensus within the Conservative Party about this.

In 1955, the first three experimental youth schools with two internal tracks (linjedelt ungdomsskole) were founded in the municipalities of Malm (in the county of Nord-Trøndelag), Sykkylven, and Ørsta (in the county of Møre og Romsdal). In 1957, experiments began in seven more counties, in 1958 in another six, and in 1959 in the last twelve (Reference TelhaugTelhaug, 1969, 36). The ninth school year was not obligatory, so many students in the experimental schools dropped out. The Experimental Council therefore suggested to parliament that experiments should be started with nine years of obligatory schooling (Reference MyhreMyhre, 1971, 113).

In the Labor Party’s manifesto for 1958–61, it was stated,

The Labor Party is of the opinion that the future expansion of schooling shall aim at an expansion of the primary school to a nine-year general comprehensive school which will become obligatory for everyone. The nine-year comprehensive school must be organized in such a way that the upper grades of the primary school become a youth school which will replace framhaldsskole and realskole. […] The Labor Party wants to erase the class division which is rooted in unequal educational opportunities.

In line with this, the Ministry of Education proposed a new folkeskole law in 1958 (Ot. prp. nr. 30 [1958], Lov om folkeskolen). In contrast to the experimental law of 1954, this proposal caused a lot of debate and split the educational parliamentary committee and parliament itself. The law made it possible for municipalities to introduce nine years of obligatory schooling, after consultation with the local school board and the ministry. The most highly contested point was whether the old school types, realskole and framhaldsskole, should be allowed to participate in the experiments with nine-year obligatory schooling (Reference TelhaugTelhaug, 1969, 55ff). The opposition parties, meaning the Conservative Party, the Christian Democrats, the Center Party, and the Liberal Party, wanted to include the old school types, but the Labor Party did not. The Labor Party had seven representatives on the parliamentary education committee, while the opposition parties had six. In the committee’s statement on the proposition (Innstilling fra kirke- og undervisningskomiteen om lov om folkeskolen, 1959), the division was expressed clearly. The Labor Party majority advocated nine-year comprehensive schooling without any reservations and wished for a final decision to be made.

The oppositional minority suggested that the municipalities themselves should choose whether to introduce nine-year obligatory schooling through the new youth school or the old school types. The debates on March 13, 1959, in the two chambers of the Norwegian parliament were lively (Forhandlinger i Lagtinget, March 13, 1959; Forhandlinger i Odelstinget, March 5, 1959). Labor Party representatives pointed to the weaknesses of the realskole, which they considered to be overcrowded and lead to exclusion, and of the framhaldsskole, which they considered to be lacking quality. They saw parallel schooling as “costly, irrational, and unfortunate in many ways,” especially in rural areas (Labor Party representative Anders Sæterøy, Forhandlinger i Lagtinget, March 13, 1959, 21). Trygve Bull, member of the parliamentary education committee for the Labor Party, expressed that, in the eyes of the Labor Party majority, the comprehensive principle itself was not to be subjected to experiments. Only the inner life of the school and its internal differentiation, pedagogy, and so forth should be developed further through experimental activity. Bull said,

What the majority wishes is to set a binding aim for the further development of the general children and youth school in our country. Without such a binding aim the development of the school system – and thereunder not least the building of schoolhouses all around in villages and cities – can come to pass under coincidental and shifting principles, and there will be a high degree of danger for significant false investments. The majority wants it to be asserted clearly and unambiguously that the social comprehensive school principle, which has been the basis of our seven-year folkeskole soon for 40 years, will in the future also be extended to the two following years.

Clearly, the Labor Party cannot be accused of making a secret of its ambitions. The aim was to exclude any possibility of survival for the old school types. This was justified by the necessity to create equal educational opportunities, independent of economic, social, and geographical background. The ambition to overcome the parallel lower-secondary-school system was rooted in the conviction that it was necessary to achieve social levelling and break down educational middle- and upper-class and urban privileges. Such privileges had not been very exclusive in Norway to start with, but they were real (Reference Aubert, Torgersen, Tangen, Lindbekk and PollanAubert et al., 1960). The old school types were associated with different degrees of status and attended by students with different class backgrounds (Reference LindbekkLindbekk, 1968, Reference Lindbekk1973, 88ff; Innstilling frå Folkeskolekomitéen av 1963 [1965], 129). This inequality was unacceptable in the eyes of the Labor Party. In the words of the Labor Party politician Gudmund Hernes,

It was the underlying philosophy, that if you want tolerance and this type of mutual respect, […] then they must learn to mix with one another. And you learn that at school. The school is the arena for this. So that was […] an important part of the reason that one did not want to preserve the old class structure which came to expression through the school structure but change the school structure to create a different society. So you can say that it was an entirely different view of the school, [using] the school to preserve what is, with school types for different classes, now I’m saying it pointedly, to a situation where you are […] using the school to create a more equal society.

Besides Fredriksfryd, there were two other conservative politicians on the parliamentary education committee at the time of the debates about the law of 1959: Per Lønning and Hartvig Caspar Christie. Christie was parliamentary representative of the Conservative Party from 1950 to 1959 and Lønning from 1958 to 1965. According to Lønning, Christie “represented the absolute oppositional extreme” compared to Fredriksfryd, and, as a result, “one noticed rather quickly that there developed a certain opposition within the conservative group of the committee” (expert interview). When the conservative parliamentary group prepared the parliamentary debate about the new folkeskole law, it was decided that Lønning should be the speaker for the party on this issue. Lønning described this in the following way:

Fredriksfryd was good at hiding his disappointment. But he did consider himself to be the Conservative Party’s number one education politician. And I had no experience as a primary schoolteacher. […] There were many in the Conservative Party’s group at the time who thought it was very nice that they had me who represented […] the young people and the future but who at the same time was critical of the social democratic Swedish education politics. […] They thought that it was very good to have me on that committee to keep the committee’s chair somewhat in check. And […] he was of average intellectual ability. And he wasn’t the kind who … even if he also spoke a few times in this folkeskole debate … he was not very skeptical of the law proposal […]. So he learned very quickly that he shouldn’t get into a discussion with me because he had nothing to win on that and above all he didn’t have the support of the majority of the Conservative Party’s group to stir up such a war on his own. They trusted that […] I would represent faith in the individual and critical moderation.

In the debates of 1959, Lønning and especially Christie showed skepticism of the comprehensive principle. Christie stated that the term “comprehensive school” (enhetsskole) had become “a propagandistic buzzword which is therefore little suited for a school program” (Forhandlinger i Odelstinget, March 5, 1959, 46). In his opinion, the realskole had been a good school that could not be blamed for its overcrowding by people who did not belong there. Instead, the alternative schools – meaning the framhaldsskole – had not been good enough and needed to be improved, not abolished. Lønning suggested that there had to be room for future school structures that differed from the “dogmatic comprehensive school scheme” of the Labor Party and warned that the danger lay in “overemphasizing unity and thereby elevating the holy general average to the main norm” (Forhandlinger i Odelstinget, March 5, 1959, 14f). Differentiation in the youth school was essential in his eyes. Nonetheless, Lønning stated,

Personally I expect […] that the so-called comprehensive school will potentially offer us a more richly differentiated school type with greater possibilities to preserve the individual student’s abilities and dispositions than the school types we have today. I expect this but I don’t see a reason to turn an assumption into a norm for future development.

In the expert interview, Lønning explained that he supported the tracked youth school because he believed that “tracking could point towards a type of differentiation where the intellectual, […] theoretical track’s advantage is underlined anew.” Presumably for this reason, Lønning supported Fredriksfryd in adding a special remark to the parliamentary education committee’s report regarding the law. Here, the two of them indicated that they expected the tracked comprehensive school to become “the school type on which it will […] be advisable to build obligatory primary education” in the future but that they thought that for the time being it should also be permissible to experiment based on the old school types (lnnst. O. II. (1959), 11). Christie did not support this remark. In contrast to Christie’s and Lønning’s antagonism, Fredriksfryd underlined the many agreements between all committee members in the parliamentary debate and pointed out that, in his view, disagreements were merely a matter of nuances (Forhandlinger i Odelstinget, March 5, 1959, 61).

The Center Party’s representatives, the Liberals, and the Christian Democrats voted with the Conservative Party against the folkeskole law of 1959, but the reasons for their skepticism were different from the Conservative Party’s. For example, the Center Party representative Inge Einarsen Bartnes stated in the parliamentary debate that the main reason for his “mixed feelings” was his worry about whether there would be sufficient financial means for rural municipalities to execute the provisions of the law (Forhandlinger i Lagtinget, March 13, 1959, 9). The Christian Democratic representative Erling Wikborg agreed that those municipalities with the worst financial conditions had to “come first in line” but also pointed out that one of the things about this reform that appealed to him most was that “we shall achieve greater equality at the outset.” In fact, he considered it “an unquestionable advantage that one, for so many years, will attend school with other youths who have completely different preconditions than oneself” (Forhandlinger i Lagtinget, March 13, 1959, 18).

The Liberal Party representative Sivert Todal specified that comprehensive schooling in grades eight and nine should be introduced more “gradually” so that the municipalities that had not even managed to comply with the folkeskole law of 1936 would have sufficient time and flexibility during a “transitional period” (Forhandlinger i Lagtinget, March 13, 1959, 16). His fellow party member Bert Røiseland warned against forcing municipalities to teach all tracks in the same building, as this could lead to “forced centralization” (Forhandlinger i Lagtinget, March 13, 1959, 26). According to the interviewed expert Hans Olav Tungesvik, there was a certain “nostalgia” within the center parties regarding the abolition of the realskole, since this school type had produced such good results in some places. However, many rural municipalities did not have realskoler. Even where they did exist, only a small percentage of rural age cohorts attended them. The main worry of the center parties was thus not the abolition of the realskole; rather, they worried whether rural municipalities would have sufficient means and flexibility to manage the transition to nine-year obligatory schooling.

The opposition was supported in its skepticism by the Association of Norwegian Secondary Schoolteachers. In 1956, the association’s yearly convention passed a statement against the abolition of the realskole and warned against any lowering of the realskole’s standard (Reference HagemannHagemann, 1992, 265; Reference MarmøyMarmøy, 1968, 49ff). In 1959, the association complained about not having been heard during the preparation of the folkeskole law and asked for the law proposal to be withdrawn (Reference MarmøyMarmøy, 1968, 56ff; Reference TelhaugTelhaug, 1969, 53). The secondary schoolteachers argued that the law proposal was not well prepared, that it anticipated the results of unfinished experiments, and that the powers it gave the ministry were too extensive (Reference MarmøyMarmøy, 1968, 59). There had been no commission to prepare the law, as had been usual earlier (Reference TelhaugTelhaug, 1969, 53f). Within the organization, the reforms were also critically discussed on the local level, where antagonistic voices could be heard in many places (Reference MarmøyMarmøy, 1968, 54ff).

The Female Teachers’ Association was also skeptical of the law of 1959, however for somewhat different reasons. Female teachers supported prolonged obligatory schooling but opposed the abolition of the framhaldsskole. They were worried that education in homemaking would lose ground. Many of them did not have the necessary educational qualifications to teach in more academic lower-secondary schools, so the reform potentially threatened their jobs (Reference HagemannHagemann, 1992, 270ff). The small association of framhaldsskole teachers opposed a merger of the old school types for similar reasons. However, many framhaldsskole teachers and female teachers were instead organized in the largest teachers’ association, the Norwegian Teachers’ Association. Representatives of the Norwegian Teachers’ Association had been more involved in the preparation of the law than the other teachers’ organizations, as they had good personal contacts with the leaders of the Experimental Council and the ministry. They agreed with the Labor Party’s ideological justifications of the reform but also profited from it structurally since the youth school was to become a part of the obligatory primary school. This opened up job opportunities for primary schoolteachers. For these reasons, they supported the reform wholeheartedly (Reference HagemannHagemann, 1992, 251ff).

Despite the opposition’s caveats, the law was passed by the Labor Party’s majority. From this point on, any municipality that wanted to introduce nine-year obligatory schooling had to do so by introducing the youth school as a new school type. Usually, the youth school would last three years, and the folkeskole would therefore be shortened to six years, but a seven-year folkeskole and a two-year youth school were also possible. Municipalities that already had realskoler could introduce a nonobligatory tenth school year.

Experiments with Reduced Organizational Differentiation

To begin with, the youth school was divided into vocational and academic tracks resembling the older school types. The tracks began in the second year of the youth school and were distinguished in the beginning mainly by whether learning a foreign language was obligatory. During the last year, the students following the practical track had fewer hours of mathematics, social sciences, and natural sciences and instead could choose from the subjects shop-floor work, homemaking, office work, agriculture, or fishing and seafaring (Reference TelhaugTelhaug, 1969, 68). The experimental curriculum from 1960 included ability grouping through kursplaner (course plans). There were three ability levels in Norwegian, mathematics, and English, while there were two in German and natural sciences. The curriculum designed by the Experimental Council suggested ability grouping from the first year of the youth school, the seventh grade – in other words, at an earlier point than had been usual in the old seven-year folkeskole. In a parliamentary debate on June 8, 1961, it became clear that the parliamentary majority did not want this. The Labor Party representatives, but also the representatives of the center parties, thought that there should be no ability grouping in the first year of the youth school and tracking should generally be more flexible.

Again, one of the arguments used by the center parties, for example by Center Party representative Einar Hovdhaugen, was that later differentiation in the new youth school would allow greater “elasticity” for rural municipalities (Forhandlinger i Stortinget, June 8, 1961, 3479). Hovdhaugen also warned that “it would be a disaster if one’s IQ should be a criterion for the choice of track” and suggested that experiments with ability grouping should be expanded to overcome the problems with current forms of differentiation. It was important to the Center Party that differentiation would not produce “losers” and lead to student apathy (Forhandlinger i Stortinget, June 8, 1961, 3480). The Christian Democrat Hans Karolus Ommedal expressed his concerns that ability grouping might lead to disorder in the school and pointed to the small rural schools as good examples of how the common teaching of all students in the classroom could be accomplished (Forhandlinger i Stortinget, June 8, 1961, 3487).

The Conservative Party alone had not taken a position for or against tracking and ability grouping in the seventh grade and wanted experiments with different models of tracking to continue, arguing that it was necessary to adapt schooling to individuals’ abilities (Forhandlinger i Stortinget, June 8, 1961). For this, they were mocked by the Labor Party politician Håkon Johnsen, secretary of the parliamentary education committee. He complained that the Conservative Party’s school manifesto of 1957 had not included tracking in the seventh school year. Johnsen pointed out that, in 1957, Fredriksfryd had been responsible for the development of the Conservative Party’s education-political manifesto:

Since then, Mr. Fredriksfryd has been shoved aside and Mr. Lønning, who has a completely different view regarding these issues, acts now as the Conservative Party’s speaker in these questions. I must therefore ask: is this just the result of an ambitious young man’s sharp elbows, or is it so that the Conservative Party has changed its view on these issues since 1957?

Over fifty years later, Lønning mentioned this remark in the expert interview as an example of how the Labor Party attempted to split the opposition parties. Fredriksfryd was not happy about the situation, nor did he give up his stand on the nine-year comprehensive school. But antagonistic voices were slowly becoming louder within the Conservative Party.

Experiments with different curricula, tracking, the introduction of a tenth grade, and ability grouping continued (Reference Seidenfaden, Körner and SeidenfadenSeidenfaden, 1977, 18ff). From 1962, students were assessed in relation to their ability group. This meant that the same grades from different ability groups were not worth the same. In 1963, the folkeskole committee was set up to work on a law proposal that would end the experimental phase of the introduction of the youth school (Reference TelhaugTelhaug, 1969, 122). In June 1965, the committee presented a report in which it had drafted reasons for and against various forms of differentiation and evaluation (Innstilling frå Folkeskolekomitéen av 1963 [1965]; Reference TelhaugTelhaug, 1969, 122ff). One aspect was the question of which combinations of tracks, course plans, and subjects would be necessary to qualify for upper-secondary schooling at the gymnas. These schools had introduced the requirement that students had to have attended the highest ability groups in Norwegian, English, German, and mathematics (Reference TelhaugTelhaug, 1969, 87ff).

The Experimental Council published several revised versions of the experimental curriculum from 1960. These were known as the blue plan (1963), the red plan (1964), and the green plan (1965). In these plans, organizational differentiation was decreased. In the blue plan, tracking was abolished. The number of obligatory, common subjects for all students rose. Differentiation was now more flexible and based on different choices of elective subjects. It was made possible for all students, no matter what their elective subjects, to choose the highest ability groups in mathematics, English, and Norwegian (Reference MyhreMyhre, 1971, 119; Reference TelhaugTelhaug, 1969, 91ff). In the red plan and the green plan, the number of obligatory subjects was increased further (Reference MyhreMyhre, 1971, 120f). In 1965, the Experimental Council started experimenting with mixed-ability classes (sammenholdte klasser, literally “kept-together classes”) in Norwegian and, from 1968, in mathematics. This was justified by studies showing that students in different ability groups did not always differ much in ability. The best students in the lowest ability groups were often better than the worst students in the highest group. The groups were not homogenous (Reference DokkaDokka, 1986, 119ff; Reference TelhaugTelhaug, 1969, 118). The trend was one toward diminishing organizational differentiation and instead using pedagogical differentiation within the classroom.

The Labor Party, the Socialist People’s Party, and the center parties supported this development, as became clear in the parliamentary debates of 1963, 1965, and 1969 (Forhandlinger i Stortinget, May 21, 1963; Forhandlinger i Stortinget, June 8, 1965; Forhandlinger i Stortinget, April 21, 1969; Reference TelhaugTelhaug 1969, 101ff). In the eyes of the Labor Party and the Socialist People’s Party, the problem with ability grouping was that it reproduced the social inequalities that had characterized the old school types. Children from the upper and middle classes were overrepresented in the higher ability groups (Reference LindbekkLindbekk, 1968, Reference Lindbekk1973; Reference TelhaugTelhaug, 1969, 143f). The fear was that ability grouping led to a stigmatization of the students in the lowest ability groups. For example, the Socialist People’s Party stated in its manifesto of 1965,

Children and youth schools should be organized so that they serve to equalize social class divisions. The school classes must be kept together most of the time, with the highest possible amount of differentiation within the class.

For the Labor Party, the abolition of organizational differentiation in the youth school was also connected to the aim of increasing the status of practical and vocational education. In its manifesto for 1966–9, the Labor Party stated for example that “practical and theoretical education must be deemed to be of equal value” and that “[t]he school system must not create social divisions as a result of differences in education.”

The center parties did not include any remarks on tracking or ability grouping in their manifestos. The details of differentiation within the school were not a priority for these parties. Most small rural schools did not have enough students to implement ability grouping anyway (Reference TelhaugTelhaug, 1969, 143). However, in parliamentary debates the center parties voiced criticism. The Liberal Party representative Torkell Tende pointed out that tracking had meant “only the choice of framhaldsskole-realskole in a new version”; to him it seemed advisable to keep classes together, even after the seventh school year, with the help of an individual “differentiation in pace” (Forhandlinger i Stortinget, May 21, 1963, 3350). The center parties’ representatives disliked the fact that grades in the different ability groups were not worth the same and that this created unfairness with respect to upper-secondary schooling. They also considered ability groups to have a stigmatizing effect. As Center Party representative Einar Hovdhaugen put it,

I’d like to underline that the nine-year school should be a comprehensive school. We are creating divisions here which in my opinion are unfortunate. Those who choose a lower ability group almost have a duty to be a little stupid.

However, the representatives of the center parties used most of their speaking time during the various parliamentary debates on education during the 1960s to address other issues closer to their hearts (see Chapter 5). They had accepted the fact that the new school type would replace the old parallel school types and rarely referred to earlier disagreements on this issue.

By 1963, the Conservative Party had given up its adherence to tracking, which was now considered to be out of date. Instead, the conservatives suggested expanding experiments with ability grouping. As Per Lønning stated in the parliamentary debate of May 1963, the abolition of tracking should not lead to the abolition of all differentiation (Forhandlinger i Stortinget, May 21, 1963, 3312ff; Reference TelhaugTelhaug, 1969, 101ff). In its manifestos, the Conservative Party made more detailed suggestions than the center parties regarding the development of schooling and differentiation. In 1965, the manifesto stated that the great pressure on schools “must not lead to a lowering of standards.” The manifesto also warned that some duties could only be fulfilled by the home and that one must avoid “creating ideas about society taking over the home’s responsibilities.” It stated that differentiation was necessary and that experiments with various forms of differentiation should be expanded to overcome problems with the current system. In 1969, similar formulations, including a reference to the realskole, were included:

The problem of differentiation must be solved through systematic and widespread experiments. Curricula must not be determined before the results of experiments have been thoroughly analyzed. […] Those students who aim at upper-secondary theoretical education must receive schooling on the same level as in the former realskole.

The Regularization of the Youth School

From 1965 to 1971, the four “nonsocialist parties” – the Conservative Party, the Center Party, the Liberal Party, and the Christian Democrats – governed, with Per Borten from the Center Party as prime minister. The youth school reform proposal, which the folkeskole committee had been preparing since 1963, was followed up. In the spring of 1967, the minister of education, Kjell Bondevik, a Christian democrat, presented the law proposal on the nine-year comprehensive school (Ot. prp. nr. 59 [1966–7] Lov om grunnskolen). The minister himself was of the opinion that “one would not have received a strongly differing proposal from another government” (quoted in Reference TelhaugTelhaug, 1969, 129). The law ended the experimental phase and regularized the new school type, the youth school. The term folkeskole (people’s school) was replaced by the more modern term grunnskole (primary school), which comprised both the barneskole (children’s school) and the ungdomsskole (youth school). The law obligated all municipalities to introduce the youth school by 1975 (Reference MediåsMediås, 2010, 45).

In April 1969, the law was passed. The only two representatives who voted against the law were from the Socialist People’s Party. Spokesperson Finn Gustavsen considered the Norwegian school to be too centralized, not democratic enough, and too strongly based on exams. In his view, schools supported a “competition and career mentality” (Forhandliger i Stortinget, April 21, 1969, 288). He also did not support the strong focus on Christian education. The first paragraph of the law (formålsparagrafen) had been a source of massive conflict revolving around the relations between church, parents, and the school. In the end, a compromise was reached that was supported by all parties, except the socialists (Reference TønnessenTønnessen, 2011, 72f; see Chapter 5).

This outcome was not what the Association of Norwegian Secondary Schoolteachers had wished for. As indicated by a survey among 1153 gymnas teachers in 1969, the introduction of the youth school was hard to accept for many of them. Over 40 percent of the interviewed teachers agreed fully or mostly with the statement that “the decision to introduce the nine-year school was taken because the many people who disagreed, mostly did not dare to publicly oppose the political buzzwords which were used” (Reference LaugloLauglo, 1972, 9). Almost 70 percent of the interviewed gymnas teachers agreed fully or mostly that nine years of obligatory schooling were too much, and 57 percent agreed fully or mostly that the old school forms of the framhaldsskole and realskole should have been expanded instead of introducing the youth school (Reference LaugloLauglo, 1972, 10). However, the secondary schoolteachers adapted to the conditions and did not organize opposition when the law of 1969 was passed.

The law did not offer any solution to the problems of differentiation, ability grouping, and evaluation. The question of differentiation was avoided. The ministry was hesitant (Reference TelhaugTelhaug, 1969, 129). Kjeld Langeland, representative of the Conservative Party, explained in the parliamentary debate that it was still too early to make a decision. Experiments had not come far enough (Forhandlinger i Stortinget, April 21, 1969, 256).

There are a few indications that the center parties were more open to the abolition of ability grouping than the Conservative Party. For example, the Liberal Party representative Olav Kortner criticized the Conservative Party’s representative Kjeld Langeland for his choice of words. Langeland had spoken of “so-called social reasons” in relation to parents’ choice of ability group. Kortner did not like the tone of this. His opinion was that ability grouping was creating “considerable social problems” and that it was necessary to “intensify experiments […] to find more socially beneficial forms [of differentiation], for example forms of mixed-ability classes” (Forhandlinger i Stortinget, April 21, 1969, 262).

In the interviews, the experts who had been active in the center parties at the time were asked why their parties did not attempt to reverse the comprehensive school reforms when in government but instead continued on the path that had been laid out by the Labor Party. To this, Hans Olav Tungesvik – then a member of the Liberal Party and later a member of the Christian Democrats – replied,

My impression is that the whole thinking about expanded obligatory schooling […], this idea of equality, the idea to give equal choices to all, it wasn’t just social democrats and the Labor Party that supported this. It was an idea which had broad support, to contribute to greater equality and greater opportunities for all. So I think there was a consensus in Norwegian politics that we should give better choices to our young people and equal choices. But we were somewhat divided with respect to the degree to which one should offer specialized choices. And the Conservative Party […], how should I put this? They have always gone further than the others in individualization. […] They have always been most concerned about giving choices which fit and not least giving choices to the most able. So there’s somewhat more of an elitist line of thought there than in the other parties. On this issue I believe that all the center parties, the Christian Democrats, Center Party, and Liberal Party, have a line of thought which is more closely related to the line of thought of the Labor Party.

Other experts, such as the Christian Democrat Jakob Aano agreed that the conservative/center parties’ government of 1965–71 was mostly a time of continuity in education politics. The Christian Democratic minister of education Kjell Bondevik supported the introduction of the youth school. Apart from the law on private schooling that was passed under his leadership (see Chapter 5), he had no interest in any far-reaching changes of the school structure.

A new committee was appointed, Normalplanutvalget, with the pedagogue Hans-Jørgen Dokka as chair. This committee had to discuss the question of differentiation again and found itself in a “painful dilemma” (Reference Telhaug and MediåsTelhaug/Mediås, 2003, 234). In its reports from 1970, the abolition of ability groups was suggested. It was said that the focus had to lie more on the individual student and that group homogenization would not solve the problem. However, mixed-ability classes depended on smaller class sizes, new teaching material, and the possibility of dividing students up in groups more flexibly (Reference DokkaDokka, 1986, 119ff).

In 1971, the non-leftist government collapsed because of internal disagreement about membership of the European Community. While the Conservative Party supported membership, the Center Party was against, and the Liberal Party and the Christian Democrats were split. The Labor Party again took over government. In April 1972, the Labor Party’s Congress and the Norwegian Federation of Trade Unions decided to support membership. However, 53.5 percent of the voters voted against membership in a referendum in September 1972. The Labor Party government left office. From 1972 to 1973, the center parties created a short-lived government, followed by new Labor Party governments from 1973 to 1981.

The Grading Debate

During the 1970s, the opposition between the social democrats and conservatives became more pronounced. Lars Roar Langslet, chair of the parliamentary education committee from 1973 to 1980 and parliamentary representative of the Conservative Party from 1969 to 1989, described the development over time:

I would say that within the Conservative Party there was a steadily growing feeling that our people who were working with school policy were too evasive and nice and just following along. And that it was important to set in place a corrective to this pedagogy of reform that was a victorious current across the board. […] But […] I believe that it was an area of consensus in many ways, the politics of schooling, in this phase. And this probably also had something to do with there not being any consciousness among education politicians on the top level within the Conservative Party that it was necessary to develop oppositional politics, it was just easier to follow along and “strew sand” over what was coming from the so-called experts. […] It became much more intensified when Lønning came in and since … when I came in, this gradually became an area of confrontation within politics during the 70s. And there were a few primary concerns over which the Conservative Party gained a strong profile, and which gave us the feeling that the Labor Party’s education politics were on the retreat.

One of the issues Langslet refers to here was the debate on grading. Grades in the first three years of the folkeskole had been abolished already in the curriculum of 1939, and from 1962, grades in the fourth grade were abolished (Reference Tønnessen, Telhaug, Skagen and TillerTønnessen/Telhaug, 1996, 23; St. meld. nr. 42 [1964–5], 15f). In the Labor Party’s manifestos, it was stated on several occasions from 1969 onward that the nine-year comprehensive school should be “free of exams.” In September 1972, the Ministry of Education appointed an Evaluation Committee (Evalueringsutvalget for skoleverket) to examine all questions related to the evaluation of students. A united parliamentary education committee agreed to the appointment of the Evaluation Committee, stating that “today’s regulation with final exams and grades based on the achieved results has inherent weaknesses” (Innst. S. nr. 287 [1971–2], 548). It was said that grading provided little motivation for the weakest students and that it could lead to an overly strong focus on achieving good exam results. In the same year, grades were abolished throughout the six-year children’s school (Reference MediåsMediås, 2010, 46; Reference MyhreMyhre, 1971, 140). This did not lead to much debate. Many supporters of the reforms, such as the members of the Primary School Committee, the Experimental Council, and education politicians within the Labor Party, anticipated that the next step would be to abolish grades in the youth school.

On February 26, 1974, the ministry, led by the Labor politician Bjartmar Gjerde, issued regulations that restricted grades in the youth school to Norwegian, English, and mathematics. This led to protests. Many parents, students, and teachers were against the regulations. In April, the Conservative Party, the Christian Democrats, the Center Party, and even the Socialist Electoral Alliance issued statements asserting that the regulations should be withdrawn and that no regulations should be issued before the reports of the Evaluation Committee had been published (Forhandlinger i Stortinget, May 8, 1974, 3126).

On May 8, 1974, the regulations were debated in parliament. In this debate, several of the Labor Party’s representatives attacked the grading system (Forhandlinger i Stortinget, May 8, 1974, 3120ff). It was pointed out that grading destroyed students’ motivation for learning and that it was unfair to judge students not based on their effort but based on their varying preconditions. Grades did not convey a nuanced picture of students’ abilities and effort but led to an overly high focus on simple and inadequate measurements. The same performance could be graded differently depending on the composition of the class, since the students’ performances were compared with each other, not with their earlier personal achievements. This meant to these Labor representatives that whether a student would be admitted to upper-secondary schooling was to a high degree the result of luck, with major repercussions for students’ lives. Grading was harmful with respect to the aim that students should feel safe and respected at school. The Labor Party politician Einar Førde summarized his position the following way:

[A] grading system and competition socialize [people] into the status quo. To all the radical people who now defend the grading system, I’d like to say: haven’t they considered that one of the most important conditions for the capitalist competition society to work is that one manages to convey this to the school in the form of grades? The grading system splits the students, and they can then be catalogued as good and bad. […] It produces losers. The grading system is the currency of the capitalist education system.

The conservative speakers made it clear that their party was opposed to any reductions in grading. On this issue, they were more united than in the debate about the structural reforms. Lars Roar Langslet expressed the conservative position:

The Conservative Party disagrees in principle with the abolition of grades and exams in the primary school. The old system was far from perfect but there have also been made great exaggerations in referring to the hunt for grades and exam pressure. A mentality of unhealthy competition must of course be dealt with, but it is not unhealthy that the school stimulates students to achieve something, to reach towards a goal. […] I think this answers a human need. The “loser” problem at school has to be tackled in a positive way. […] We won’t solve this by taking away the measuring scales.

Like Lønning, who had argued against the abolition of grading in the folkeskole in the 1960s (Forhandlinger i Stortinget, June 8, 1961, 3474; Forhandlinger i Stortinget, June 8, 1965, 3697f), Langslet argued that written evaluations could lead to more arbitrariness than grades (Forhandlinger i Stortinget, May 8, 1974, 3126).

The center parties consented to the abolition of grading in the children’s school but stood closer to the Conservative Party than to the Labor Party regarding the question of grading in the youth school. The Center Party representative Ola O. Røssum declared that “the school must not needlessly contribute to and strengthen career chasing and demands for achievement” and that it was therefore sensible to have abolished grades in the children’s school (Forhandlinger i Stortinget, May 8, 1974, 3120ff). But he deemed it impossible to abolish grades in the youth school as long as upper-secondary schooling had not been expanded sufficiently to grant access to everyone. The Christian democrat Kjell Magne Bondevik agreed that while the intention might have been good, the regulations were “a pedagogical and political mistake.” Like Røssum, he thought that the abolition of grades in the children’s school had been sensible but that selection for upper-secondary schooling necessitated grading in the youth school. “Nuanced evaluations” could possibly be added to or replace grades at some future point, “when there is a basis for it.” He reacted strongly to the accusations of the Labor Party that had been calling opposition to the reduction of grading an expression of “conservative currents in the population.” He did not want to be identified with the label “conservative” and thought that the Labor Party was flattering itself by labeling the reduction of grading “a radical reform” (Forhandlinger i Stortinget, May 8, 1974, 3128f). The Liberal Party representative Hans Hammond Rossbach, a secondary schoolteacher, agreed that abolishing grades in the youth school was a bad idea since the necessary conditions for such a step were not met. He pointed out that both the students’ and the teachers’ associations were opposed to the new regulations (Forhandlinger i Stortinget, May 8, 1974, 3134).

He thus pointed to a difficulty for the Labor Party. Not surprisingly, the Association of Norwegian Secondary Schoolteachers was critical of the abolition of grades. However, as was lamented by several of the Labor Party’s speakers, the Norwegian Teachers’ Association could also not be depended on regarding this question. In earlier statements, the organization had suggested that grading in the youth school should be reduced to the subjects of Norwegian, mathematics, and English and had supported the reduction of grades to a minimum. But in March 1974, the primary schoolteachers sent a letter to the ministry complaining that they had not been heard and stating that they opposed the reduction of grading (Forhandlinger i Stortinget, May 8, 1974, 3135). Internally, they were split on the issue. As Kari Lie, at this point secretary of the Norwegian Teachers’ Association and formerly active in the Female Teachers’ Association, stated, “There were several people on the national board who thought I was hopeless for wanting to keep grades in the system” (expert interview). According to Lie, one reason for this disagreement was that many primary schoolteachers were not as radical as the progressive pedagogues who supported the abolition of grading. Like herself, some found it difficult to produce written evaluations of students’ achievements and thought that such evaluations could be more harmful than a bad grade.

Furthermore, even the Labor Party itself was internally split on the issue, as was confirmed by several of the interviewed experts. In his book, Reference LangsletLangslet (1977, 47) quotes a Gallup poll, according to which 89 percent of Labor Party members supported grades in the youth school, against only 9 percent who wanted them abolished. In the expert interview, he added that during this phase he had met “central people in the Labor Party who were quite crestfallen about how these school reformers had harried [them]” (expert interview).

Despite all this, the majority of the Evaluation Committee concluded in its first report in 1974 that grades should be abolished in the youth school (NOU 1974: 42 (1974) Karakterer, eksamen, kompetanse m.v. i skoleverket, Eva I). The minority agreed with abolishing grades in the children’s school but thought that youth school students should be given grades if they wanted them. Another minority even wanted to abolish grades in upper-secondary schools (NOU 1974: 42 [1974] Karakterer, eksamen, kompetanse m.v. i skoleverket, Eva I). In its second report from 1978, the committee suggested that entry to the gymnas should become independent of grades (NOU 1978: 2 [1978] Vurdering, kompetanse og inntak i skoleverket, Eva II). These reports created much debate. Over 2600 comments were sent in during the hearing. Two-thirds of those were negative about abolishing grades in the youth school (Reference TønnessenTønnessen, 2011, 79ff; Reference Tønnessen, Telhaug, Skagen and TillerTønnessen/Telhaug, 1996, 26). The Norwegian Teachers’ Association disagreed with the committee’s proposals, even though they showed a willingness to discuss the grading system based on further research (Reference Tønnessen, Telhaug, Skagen and TillerTønnessen/Telhaug, 1996, 28).

As a result of the massive opposition even within the Labor Party’s own ranks, the Labor Party minister Bjartmar Gjerde decided to backpedal. After the debate of May 9, 1974, he had already repealed the regulations on the reduction of grading. The socialist school reformer and primary schoolteacher Kjell Horn described the change of course as follows:

There had been put in place this Evaluation Committee which concluded that grading should not be used in an obligatory primary school. And I was sent around the country as consultant of the Primary School Committee to argue for this system on behalf of the […] ministry. I thought that I was doing a rather good job but apparently not good enough because this reform had no enthusiasm among the Norwegian people. Then one day, Gjerde comes to my office and stares at something. He is not looking at me but past me. And then he asks me what I am doing, and I tell him and he says “Yes, but grading, that is not a topic for the Labor Party any longer,” he said. Oh dear!

The Final Debate on Differentiation

The debates on differentiation in the youth school also became more polarized during the 1970s. The Conservative Party became more clearly antagonistic, but on this matter the Labor Party asserted itself. In 1972, the entire parliamentary committee had agreed with the suggestion of the Normalplanutvalget, of the Primary School Committee, and of the Labor Party–led ministry to abolish the current ability-group system, which was producing inequality of opportunity in the eyes of almost everyone (Innst. S. nr. 287 [1971–2]). This decision came into effect in 1975 with the new curriculum (Mønsterplanen for grunnskolen, M74). The parliamentary committee’s statement of 1972 also contained the following sentences:

The committee would, however, like to assert that the primary school will need various forms of organizational differentiation also in the years to come. In the long term, it should be a goal that the individual school can develop the form of differentiation which fits best to local conditions. (Innst. S. nr. 287 [1971–2], 547)

In 1973, the manifesto of the Conservative Party asserted that the individual school should have responsibility for choosing the best form of differentiation. The conservative manifesto of 1977 opposed mixed-ability classes:

With today’s scarce resources, a rigorous implementation of the principle of classes that are “kept together” means that one shoves a regard for students’ needs into the background. The Conservative Party thinks that it is necessary to develop satisfying forms of organizational differentiation, while keeping the class as a social unit.

Lars Roar Reference LangsletLangslet’s (1977) book serves to illustrate the growing conservative antagonism. In the book, Langslet did not question the nine-year comprehensive school as such and showed some sympathy for the aim of developing a spirit of community between all youths, independent of social background. But he also wrote,

I myself supported the “farewell” to the ability-group system [in 1972] and don’t want to deny my responsibility for this. But I must admit that I have become doubtful whether this was right. I think the ability-group system was, pedagogically, a good solution for the question of differentiation and presumably better than the new regulation with mixed-ability classes […] is likely to become.

He did not support special schools for especially able children, which could “justly be branded as an attempt to create ‘apartheid’ in the school” (Reference LangsletLangslet, 1977, 62). Nonetheless, he claimed that the ablest students had been neglected by social democratic school reforms and that social democrats had no respect for inequalities but instead aimed exclusively at erasing or hiding them (Reference LangsletLangslet, 1977, 34ff, 61f). He also pointed out that, while much could be done to give disadvantaged children better chances, political measures “can under no circumstances go so far that all important inequalities disappear” (Reference LangsletLangslet, 1977, 39). This “pessimistic insight” was hard for socialist education politicians to accept (Reference LangsletLangslet, 1977, 39). He made the further accusation that to the socialists, “competition in itself [was] an evil which mirrors the basic inhumanity of the capitalist system” (Reference LangsletLangslet, 1977, 40).

In the interview, Langslet dubbed social democratic education politics “a sentimental school ideology,” aimed at turning the school into a counterpart of the “abominable capitalist society outside, where demands for performance at work are made and where there is competition and all kinds of ugliness” (expert interview). By way of comparison, the socialist politician Theo Koritzinsky pointed out that competition and hierarchies were important mechanisms for conservatives. Even though they would never have said that they supported differentiation with the aim of reproducing class differences, “they know full well that this is what can happen … and for them it’s not a problem; that’s how it is; that’s life; that’s how we are made” (expert interview).

In May 1979, these oppositions became visible in the final parliamentary debate on permanent ability grouping. The exact rules regarding organizational differentiation had been unclear since 1972 (Stortingstidende [1976–7], 2100 f; Stortingstidende [1977–8], 2694ff). For this reason, the Ministry of Education issued new regulations stating more clearly that permanent ability grouping throughout the course of a whole year was not allowed. Grouping students was only allowed on a short-term basis (St. meld. nr. 34 [1978–9], 11).

In the debate on these regulations, the Conservative Party’s representatives criticized the Labor Party’s “equality ideology” in harsh words. The conservative politician Håkon Randal, a member of the parliamentary education committee, thought that the abolition of ability grouping would lead to a “lowering of standards” and that it violated the school law (Forhandlinger i Stortinget, May 11, 1979, 3360). His fellow party member Tore Austad considered it a “great and very deplorable step backwards” to make ability grouping throughout a school year unlawful (Forhandlinger i Stortinget, May 11, 1979, 3367). Another conservative member of the parliamentary education committee, Karen Sogn, complained about the Labor Party’s “hysterical reaction” to the Conservative Party’s support for more far-reaching organizational differentiation. She quoted the Labor Party politician Reiulf Steen, who had accused the conservatives of supporting “apartheid in the school” and of working for an “elite school.” This, to her, was proof that the Labor Party was elevating “ideological considerations” above what was best for the individual student (Forhandlinger i Stortinget, May 11, 1979, 3373f). The conservatives also demanded that the Experimental Council be abolished, that structural reforms end, and that the focus should now be on improving the quality of teaching by introducing stricter demands regarding the content of schooling (Forhandlinger i Stortinget, April 17, 1975; Forhandlinger i Stortinget, April 20, 1978; Forhandlinger i Stortinget, May 11, 1979; Reference LangsletLangslet, 1977).

The Christian Democrats and the Center Party sided with the Conservative Party against the new regulations (Innst. S. nr. 215 [1978–9]). Even though the Center Party and Christian Democrats had agreed in the 1960s and early 1970s that the ability-group system was unfair, they now defended local schools’ freedom with respect to organizational differentiation, including ability grouping. The Christian Democrat Olav Djupvik attacked the Labor Party for turning pedagogical questions into “ideological questions” in accordance with its “misunderstood equality ideology”:

If forms of instruction can no longer, without ideological concerns, vary based on what schools and the home at any time consider best for the individual student, we cannot, in my opinion, claim for ourselves to be fighting for equality. We have then accepted that certain forms of instruction are discriminatory. And that is an expression of a discriminatory attitude.

To this, the Labor Party representative Kirsti Grøndahl replied,

Mr. Djupvik talked much about the Labor Party’s “misunderstood equality ideology.” The mistake is not that the Labor Party has a misunderstood equality ideology. The mistake is that Djupvik has misunderstood the Labor Party’s equality ideology. My speech also included a very negative remark about homogenous ability groups, Mr. Djupvik said, and that is indeed true. […] We want to do something about this and it is of course nice that Mr. Djupvik has also understood that what we are against is something negative.

Clearly, there was little sympathy between the Christian Democrats and the Labor Party at this point. However, the debate was dominated primarily by the antagonism between the Labor Party and the Conservative Party, whereas most representatives of the center parties did not choose equally strong words. The Center Party representative Leiv Blakset pointed out that he would like to “strongly underline” that it was right to focus on creating the best conditions, especially “for the weakest students,” though this should not mean neglecting the most able (Forhandlinger i Stortinget, May 11, 1979, 3368). His fellow party member Johan Syrstad regretted that the debate had been dominated by “buzzwords” and that the participants had “gone into the trenches.” He also thought that the Labor Party’s position was not so far removed from his own, since they agreed on the most important point: to give “considerable local freedom to the individual school.” He thought that it was a better idea to “let those who deal with the problems of daily life” make the decisions, instead of introducing “new, centrally issued regulations” (Forhandlinger i Stortinget, May 11, 1979, 3381). In other words, for the Center Party it was mostly a matter of principle to oppose central regulations.

The Liberal Party was weak at the time and not represented on the parliamentary education committee. The Liberal Party representative Odd Einar Dørum made it clear that his party sympathized more with the point of view of the Labor Party, even though he thought it difficult to detect “great oppositions” in the parliamentary committee’s report:

Both groups agree, and the Liberal Party supports this view, that grouping shall be based on local conditions and that one should use common sense in this regard. Furthermore, the Labor Party says that one wants to avoid long-term grouping. This is a view I share. […] We supported the abolition of the ability-group system, and we want to assert that this is a definite position. We are happy to state that we cannot see – if we base ourselves on the words which have been chosen here – that there is anyone who wants to return to the ability-group system.

Dørum thus pointed to a difficulty faced by the opponents of the new regulations. It was hard to argue for organizational differentiation against the accusations of the Labor Party and the Socialist Left Party that one wanted to reintroduce the ability-group system through the back door. This system had become utterly unpopular. The directives were eventually passed by the parliamentary majority of the Labor Party and the Socialist Left Party. Due to this decision, a long-term development from parallel school types to tracked lower-secondary schooling, to ability grouping, and finally to the abolition of all organizational differentiation came to an end.

When the conservatives regained power in 1981, they abolished the Experimental Council and changed curricula. However, they did not attempt any far-reaching reversal of the structural reforms. According to Langslet, the main reason for this was “that one was fed up with reforms” and that the school now deserved “a quieter period where one should instead make the best out of the existing system.” Furthermore, he pointed out that “we weren’t a majority government, so we had to take into consideration whether this could receive support in parliament and such a total reversal would presumably have been a utopian project” (expert interview).

It would be wrong to say that changes came to a complete halt at this point. The regulations of the 1980s focused on the content of schooling more than on the outer structure of the system. During the 1990s, the comprehensive reform ideas were taken up again by the Labor Party’s minister of education, Gudmund Hernes. Under Hernes’ leadership, the age of school enrolment was lowered from seven to six years, thereby extending the children’s school to seven years again and comprehensive education to ten years. Upper-secondary education was also reformed further. However, at this point, the historical narrative of this chapter comes to a close. The final words shall be given to the Labor Party representative Einar Førde, minister of education from October 1979 to October 1981, who pointed out the following in the final parliamentary debate on organizational differentiation in May 1979:

This demand for “peace in the school” apparently has a totally debilitating effect on the ability for thinking of the conservatives. If it is so that they are unhappy with the situation of today, they must of course reform themselves out of it – unless they are so naive as to believe that there is a way back to what was, back to the framhaldsskole and the realskole. […] But they can hardly be so naive. This way back is of course as closed as the way back to the Garden of Eden. The social unrest and the unrest in the school which would arise if one attempted to turn back to the systems we have left behind would be unrest of a wholly different character and of a wholly different seriousness than the unrest which is now used as an excuse for not doing anything about what one doesn’t like.

Comprehensive School Reforms in North Rhine–Westphalia

In 1959, the “framework plan for the remodeling and standardization of the general school system” sparked off new reform discussions. During the second half of the 1960s the integrated comprehensive school became a topic of debate. In 1966, the last Christian democratic government of NRW introduced the Hauptschule and nine years of obligatory schooling. In 1969, the first seven integrated comprehensive schools were founded and by 1975, another sixteen such schools followed. Within these schools, organizational differentiation by ability grouping was the rule. In the early 1970s, even the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) was open to the introduction of so-called cooperative comprehensive schools. During the 1970s, the opposition to comprehensive schooling grew and reformers’ aim that the integrated comprehensive school should replace all parallel school types was gradually given up. In the second half of the 1970s, the NRW government attempted to introduce the cooperative school as an additional school type that was a combination of the Hauptschule, Realschule, and Gymnasium, with comprehensive schooling in grades five and six followed by three tracks. This led to the collection of 3.6 million signatures against the reform. The government withdrew the law. The integrated comprehensive school became an additional school type beside the older ones and lost its experimental status in 1981. In the following, these reforms are discussed chronologically.

Early Debates on Comprehensive and Nine-Year Obligatory Schooling

In NRW, the initial postwar years were a time of restoration. In education politics, the main conflict was about denominational schooling (see Chapter 5). In 1959, the German Committee for the Education and School System (Deutscher Ausschuss für das Erziehungs- und Bildungswesen) published its “framework plan for the remodeling and standardization of the general school system” (Rahmenplan zur Umgestaltung und Vereinheitlichung des allgemeinbildenden Schulwesens). This document suggested the upgrading of the upper grades of the Volksschule, termed Hauptschule in the document, by introducing a ninth and later tenth school year, an obligatory foreign language, and ability grouping in important subjects. It also suggested the introduction of a two-year transition or orientation stage after the first four years of schooling in the lower Volksschule, termed Grundschule. Grades five and six should serve to prolong the period of decision-making for one of the secondary school types. The SPD, the FDP, and the different organizations of Volksschule teachers supported these suggestions, while the CDU was hesitant (Reference Herrlitz, Hopf and TitzeHerrlitz et al., 2009, 168).

The Godesberg manifesto of the SPD from 1959 stated that “all privileges in access to educational institutions must be eliminated” and that “for any able person the way to secondary schools and educational institutions must be open.” It also demanded ten years of obligatory schooling. In its manifesto for the federal state elections in NRW in 1962, the SPD stated,

To pave all ways for all children so that they can let their strengths unfold and develop their dispositions without restrictions, for the good and for the use of humanity and for their happiness – is this not a task which would be worth the strongest commitment? […] Neither the father’s wallet nor the social standing of the family, neither the large or small number of children nor the denomination or the belonging to a group of the people – nothing should stand debilitatingly in the way, when the aim is to let unfold and develop the gifts and abilities of the young person.

The manifesto informed voters that the NRW SPD had passed a motion in 1959 in response to the “framework plan.” They had suggested the introduction of an “orientation stage” for all children in grades five and six that would prepare them for the school type they would attend from grade seven. It was argued that this could prevent a “draining” of the Volksschule and an overcrowding of secondary schools “with students who are unfit for scientific work.” Extending comprehensive schooling by two years was thus presented as a measure that would strengthen selection at a later point.

In 1960, the Education and Science Workers’ Union published its “Bremen Plan” (Bremer Plan), in which it suggested an extension of comprehensive schooling by two years. From grades seven to ten, schooling should be organized in three tracks. This was justified as follows:

The school of a modern society as a society of free and equal people should be realized through a dynamic, unified ladder system of schooling. […] The school of the modern society should be a school of social justice, in which there is equality for all at the start, in which all normal children, by staying together until the end of the sixth grade, gain real experiences of companionship, before differences in ability and diligence have a separating effect.

The Bremen Plan led to fierce reactions from the CDU and the Catholic Church because it also envisaged a secularization of the school system. The plan was said to be indistinguishable from the communist school program of the German Democratic Republic (Reference KopitzschKopitzsch, 1983, 190). It led to controversial debates within the union and soon disappeared from the agenda. In the following years, the union’s national chair, Heinrich Rodenstein, preferred to speak of “educational centers” in which traditional school types should be combined to increase permeability (Reference KopitzschKopitzsch, 1983, 230).

In the early 1960s, education debates accelerated, and Georg Reference PichtPicht (1964) coined the phrase “the German educational catastrophe,” referring to the low number of secondary school graduates and the large urban-rural and class inequalities. From 1962 to 1966, Paul Mikat from the CDU became minister of education in the last CDU-FDP coalition in NRW. He was young, more inclined to reforms than his predecessor, Werner Schütz, and supported experiments with tracked comprehensive schools (Reference MikatMikat, 1966, 38; Ministry of Education and Cultural Affairs of NRW, 1965). He did not always have the support of more conservative CDU representatives. The former CDU politician Wilhelm Lenz mentioned that Mikat “would have been willing to do more” if the minister of finance had not restrained him (expert interview). During the first half of the 1960s, the CDU-FDP government created new paths to the Abitur exam by extending evening schooling and upper-secondary schooling for Realschule graduates and by increasing the number of Realschulen and Gymnasien, especially in rural areas (Reference DüdingDüding, 2008, 488ff; Ministry of Education and Cultural Affairs of NRW, 1965; Ministry of Education and Cultural Affairs of NRW, 1967). This was not subject to much debate, as there was consensus that the number of Abitur graduates needed to be increased (Reference FälkerFälker, 1984, 101f).

In July 1964, the party executive committee of the SPD passed the “Educational-Political Guidelines” (Bildungspolitische Leitsätze), which more boldly than before suggested replacing parallel schooling with a ladder system of education and employed the term “comprehensive school” (Gesamtschule) for the first time. The social democrats now suggested a six-year primary level of schooling followed by a four-year lower-secondary level and a three-year upper-secondary level. For the lower-secondary level, they envisaged a common core of teaching in addition to differentiated teaching in courses and ability groups. They considered the introduction of a two-year orientation stage in grades five and six and increased permeability between the traditional school types to be steps in the right direction. In the long term, all school types should be integrated into one organizational unit (Vorstand der SPD, 1964, 12ff). The NRW chapter of the Education and Science Workers’ Union (GEW) also included the integrated comprehensive school (integrierte Gesamtschule) in its program in 1965.

The Association of Philologists, on the other hand, opposed comprehensive schooling in its Göttingen Resolutions published in 1964:

The differentiation of modern working life demands a richly structured school system. […] A leveling comprehensive school [nivellierende Einheitsschule] cannot do justice to the state of society today or in the future. Just as those who are endowed below average need special support, those who are endowed above average are also eligible to be supported as early and as much as possible. Support which starts too late impedes the development of endowments and sentences those who are endowed above average to boredom and thus to the degeneration of their innate possibilities. At the same time, the human development and educational support of the more weakly endowed are impeded. […] For this reason, a pillared general and vocational school system is indispensable.

In the same document, the Association of Philologists supported an educational expansion based on preparatory forms of the Gymnasium and Realschule [Aufbauschulen /Aufbauklassen]. It also emphasized parents’ rights to decide about the education of their children. Permeability between the school types was supported to a certain degree but not “at any time point” since this would lead to “a lowering of achievements.” The philologists viewed the Gymnasium as the school of the future elites and therefore as particularly important. It was stated,

The Gymnasium needs to stick to the principle of achievement; because for every nation the endowments are its most valuable property. An efficient economy is not […] imaginable without a great number of personalities who are scientifically qualified and qualified in character.

In October 1964, the Düsseldorf Agreement of 1955 between the federal states was renegotiated. The result was the Hamburg Agreement. This agreement stipulated nine years of obligatory schooling and allowed ten years of obligatory schooling. It suggested the introduction of the Hauptschule – meaning the upper stage of the Volksschule – as a secondary school type in addition to the Realschule and Gymnasium, and a two-year transition stage in grades five and six, which should be common for all schools. These were discretionary clauses. Upper-secondary courses, preparing Realschule and Hauptschule graduates for the Abitur, were regulated. A foreign language, usually English, was introduced to the curriculum of the Volksschule. Experiments with new school structures were allowed (Reference FriedeburgFriedeburg, 1992, 349). The Ministerpräsidenten of the federal states governed by the CDU also signed this document, which is an indication of the drive toward reform.

In November 1964, the CDU organized a political congress in Hamburg, at which new guidelines for “education in the modern world” were passed. Here, the CDU stated, “the German education system must be shaped so that everyone, who is […] capable, is offered his chance.” It supported increased “permeability” of the school system through the introduction of preparatory forms of the Gymnasium and Realschule [Aufbauschulen], which should recruit able students from the Volksschule. “In our education system, there must be no ‘one-way streets,’” the guidelines said. Nevertheless, the guidelines emphasized that a shortening of the Gymnasium would endanger academic standards. A comprehensive school was considered unsuitable for the aim of supporting all talents in the population. The paper also opposed an obligatory orientation stage in grades five and six.

Educational planning was intensified. In 1965, the German Educational Council (Deutscher Bildungsrat) was founded as the successor of the above-mentioned German Committee. It was comprised of an educational commission consisting of scientists and an administrative commission, which included school administrators and educational politicians. The council published reports, studies, and recommendations for experiments and reforms (see e.g. Reference Herrlitz, Weiland and WinkelDeutscher Bildungsrat, 2003 [1969]; Deutscher Bildungsrat, 1973; Deutscher Bildungsrat, 1975).

In June 1966, the CDU-FDP government of NRW passed a law on obligatory schooling (Schulpflichtgesetz) that regulated the introduction of nine years of obligatory schooling. The law introduced the institutional distinction between the four-year primary school (Grundschule) and the five-year upper stage of the Volksschule, now called Hauptschule (Reference FälkerFälker, 1984, 75, 114). However, the Hauptschule remained attached to the Grundschule. This was opposed by the SPD. Social democrats voted against the law because they did not find it far-reaching enough (Landtag NRW, May 11, 1966; Landtag NRW, May 25, 1966).

On June 14, 1966, the NRW section of the Association of Philologists organized a rally in Essen to protest the new trends in education politics. The chair of the NRW section, Clemens Christians, argued at the rally that it was wrong to assign the Gymnasium the achievement of equality of opportunity. Equality of opportunity could only be achieved through additional support in preschool (quoted in Reference FluckFluck, 2003, 215). Reference FluckFluck (2003, 216) also quotes vice-chair Hanna-Renate Laurien, who later became minister of education in the Rhineland-Palatinate for the CDU. She said,