Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- List of Abbreviations

- 1 Introduction

- 2 East Pokot: A Place and its People

- 3 Pokot Pastoral Livelihoods

- 4 The Paka Community

- 5 Environmental Changes in East Pokot

- 6 Socio-Ecological Transformations in the Agro-Pastoral Highlands

- 7 Ecological Change and Local Livelihoods: Scientific and Pokot Perspectives

- 8 Ecological Invasions: Agents of Socio-Ecological Transformation

- 9 Ecological Challenges and Social Transformations

- Appendix: Lists of Plant Names (Pokot–Scientific and Scientific–Pokot)

- Bibliography

- Index

- Future Rural Africa

2 - East Pokot: A Place and its People

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 16 July 2022

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- List of Abbreviations

- 1 Introduction

- 2 East Pokot: A Place and its People

- 3 Pokot Pastoral Livelihoods

- 4 The Paka Community

- 5 Environmental Changes in East Pokot

- 6 Socio-Ecological Transformations in the Agro-Pastoral Highlands

- 7 Ecological Change and Local Livelihoods: Scientific and Pokot Perspectives

- 8 Ecological Invasions: Agents of Socio-Ecological Transformation

- 9 Ecological Challenges and Social Transformations

- Appendix: Lists of Plant Names (Pokot–Scientific and Scientific–Pokot)

- Bibliography

- Index

- Future Rural Africa

Summary

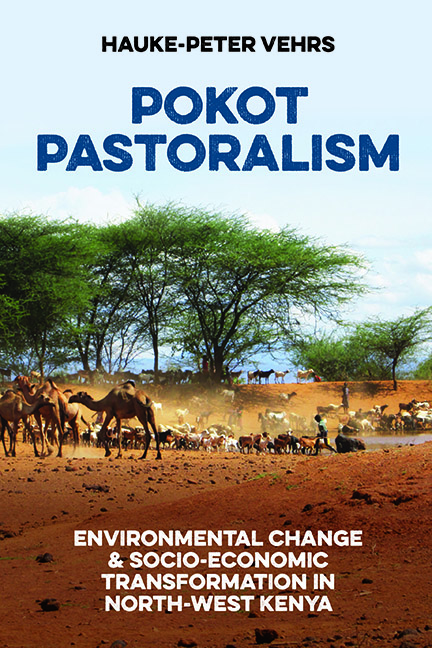

The Tiaty Constituency, formerly known as East Pokot District – is located in the north of Baringo County and extends over an area of approximately 4,500 km2 in the East African Rift Valley with an official population number of about 153,344 (Republic of Kenya, 2019). Lake Baringo is located in the south of the constituency's boundaries, and the Rift Valley escarpment rises in the east and the west of East Pokot towards Elgeyo-Marakwet, Laikipia and Samburu Counties.

Fieldwork was conducted in Chepungus on the southern slopes of Mt Paka, an extinct volcano in central East Pokot right in the centre of the Rift Valley. Most of the research was done in the Paka community, which consists of approximately 600 people who speak the Pokot language and, to a limited extent, Kiswahili. My interest focused on the pastoral ways of life, how environmental changes are having an effect on pastoral livelihoods and how both changes in the environment and social transformations influence each other. I decided to live in the pastoral parts of East Pokot extending from Lake Baringo in the south up to Silali and the Tiaty mountains in the north. Due to violent conflicts with Turkana pastoralists in the north and a rising conflict over pastures with Il Chamus and Tugen people in the south, I chose to live in central East Pokot.

The taste of fieldwork

Immersion into the field did not happen in a pre-determined, logical way, but, as in most anthropological fieldwork, largely intuitively. This intuition includes the senses, especially those over and above the visual dimension of fieldwork. Although visual experiences of the field often dominate in first impressions, tasting, smelling, and feeling the field are, in many ways, just as important. To live with the people in the field and share the same experiences and life-world, instead of imposing our own reasoning on them, makes an important difference for anthropological fieldwork. As Stoller describes for his research among the Songhay in the 1970s, people would lie to him if he did not ‘learn to sit with people’ (1989, p. 128). Most often, the preconditions of friendship and mere collaboration are shaped differently in the field. To be with people includes more than mere presence and frankness.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Pokot PastoralismEnvironmental Change and Socio-Economic Transformation in North-West Kenya, pp. 14 - 33Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2022