Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Prologue

- 1 A Modern Mask: From Deburau to The Tramp

- 2 First Examples of an Effeminate Pierrot: From Verlaine to Lorca

- 3 Pierrot/Lorca: Alter Ego for a Young Poet

- 4 Lorca/Pierrot: Between Painting and Theatre

- 5 Love Game and Masquerade: Dalí/Lorca

- 6 Perlimplín/Lorca/Pierrot: Frustrated Desire

- 7 A White Clown for a Black Desire: El público and Así que pasen cinco años

- Epilogue

- Bibliography

- Index

7 - A White Clown for a Black Desire: El público and Así que pasen cinco años

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 22 February 2023

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Prologue

- 1 A Modern Mask: From Deburau to The Tramp

- 2 First Examples of an Effeminate Pierrot: From Verlaine to Lorca

- 3 Pierrot/Lorca: Alter Ego for a Young Poet

- 4 Lorca/Pierrot: Between Painting and Theatre

- 5 Love Game and Masquerade: Dalí/Lorca

- 6 Perlimplín/Lorca/Pierrot: Frustrated Desire

- 7 A White Clown for a Black Desire: El público and Así que pasen cinco años

- Epilogue

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

The presence of clownesque imagery extends throughout Lorca’s artistic works, even when during his moments of greatest genius it is redefined by surrealism. This is the case in both the film script Viaje a la luna (1929–30) – to which I will refer tangentially throughout this chapter – and the stage plays El público (1929) and above all, Así que pasen cinco años (1931). This is in spite of the fact that the masks of commedia dell’arte were not absorbed by surrealism, since they were conceived by the leading lights of the avant-garde movement as the remains of an outmoded art which, although it had undergone a rebirth in the hands of the decadents, modernists and even the cubists (we must remember the critical role that Harlequin played in the decomposition of traditional conceptions in the cases of Picasso or Juan Gris), was still set aside from the subconscious introspection that they aimed for. We should then ask ourselves why it was that when Lorca discovered the streets of New York, the asphyxiating loneliness of a city peopled by the dead – ‘Yo denuncio la conjura/ de estas desiertas oficinas/ que no radian las agonías,/ que borran los programas de las vacas estrujadas/ cuando sus gritos llenan el valle/ donde el Hudson se emborracha con aceite’ (‘Nueva York (Oficina y denuncia)’, 1990b: 203) – alongside the most crushing modernity, this served to further underscore the recurrence of the Pierrot mask and Harlequin, to the point that they became constituent elements as projections of the respective protagonists of his two greatest surrealist dramas, El público and Así que pasen cinco años.

I believe that one of the keys, which has been underexplored until now – except for Lorca’s insertion into the New York theatre scene of 1929 and 1930 undertaken by Anderson (1993) – lies in imagining the gay scene that Lorca encountered in the city and what impact this public expression of a silenced feeling might have aroused in him, however partially, on returning to Spain. As Christopher Maurer and Andrew Anderson rightly point out, the time that Lorca spent in New York can be divided into two distinct periods (2013: xi–xii).

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

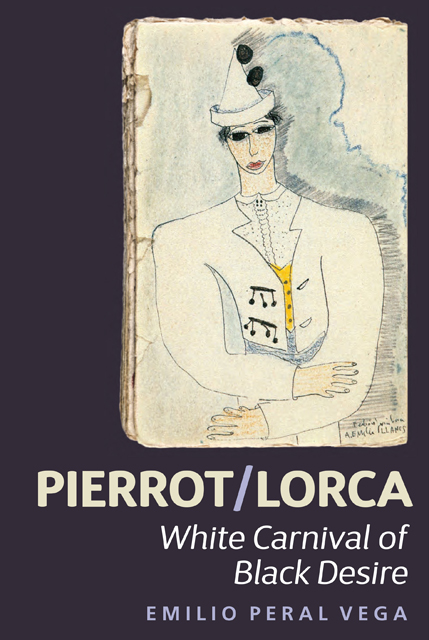

- Pierrot/LorcaWhite Carnival of Black Desire, pp. 109 - 138Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2015