Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Prologue

- 1 A Modern Mask: From Deburau to The Tramp

- 2 First Examples of an Effeminate Pierrot: From Verlaine to Lorca

- 3 Pierrot/Lorca: Alter Ego for a Young Poet

- 4 Lorca/Pierrot: Between Painting and Theatre

- 5 Love Game and Masquerade: Dalí/Lorca

- 6 Perlimplín/Lorca/Pierrot: Frustrated Desire

- 7 A White Clown for a Black Desire: El público and Así que pasen cinco años

- Epilogue

- Bibliography

- Index

1 - A Modern Mask: From Deburau to The Tramp

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 22 February 2023

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Prologue

- 1 A Modern Mask: From Deburau to The Tramp

- 2 First Examples of an Effeminate Pierrot: From Verlaine to Lorca

- 3 Pierrot/Lorca: Alter Ego for a Young Poet

- 4 Lorca/Pierrot: Between Painting and Theatre

- 5 Love Game and Masquerade: Dalí/Lorca

- 6 Perlimplín/Lorca/Pierrot: Frustrated Desire

- 7 A White Clown for a Black Desire: El público and Así que pasen cinco años

- Epilogue

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

Pierrot, the white mask, lonely and pathetic, a major icon of romantic and symbolist aesthetics, had by the nineteenth century travelled a long and winding road which had not always been easy. Pierrot, as we conceive of him today, has little or nothing to do with his immediate ancestor, Pedrolino of Italian commedia dell’arte, beyond an external appearance which, while not identical – the ‘Colin’ style hat being replaced by a black handkerchief that contrasted with the exaggerated pallor of the face – does bear some resemblance. Our modern Pierrot, thanks to a process of development in France, is no longer a ductile, pusillanimous, mocking and ignorant servant, condemned to a secondary role in the shadow of the always magnificent Harlequin, Pantalone, Pulcinella and the inexhaustible Columbine. His role as secondary zanni allowed him no more prominence than appearances in a series of farcical scenes, most of these in dubious taste, while the rest of the masks strutted their stuff on stage.

In order to better understand the qualitative leap that Pierrot experienced in France at the outset of the nineteenth century, it is crucial that we take a look at one of the most influential figures in European culture of the era, in spite of his role as an actor, or rather mime: Jean-Gaspard Deburau (Bohemia, 1796–Paris, 1846), the sixth son of a family of acrobats who defined themselves as ‘artistes d’agilité’ (Baugé, 1995: 4). Replacing the magnificent actor Frédérick Lemaître, Deburau joined the Théâtre des Funambules, a legendary space – albeit small in size – which sat on the famous Boulevard du Crime and went on to be a key element in the development of mime in Paris. Having joined the Funambules, at first as an actor in the ‘pantomime sautante’ – an exhibition of physical prowess – he then went on to play, from 1819 onwards, the role that would make him a crucial point of reference: Pierrot. He gave the pale-faced buffoon a new dimension, midway between comedy and tragedy, and above all granted him a versatile dramatic presence that went against the current of a tradition in thrall to preordained structures, and which had not been able to tap his full potential.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

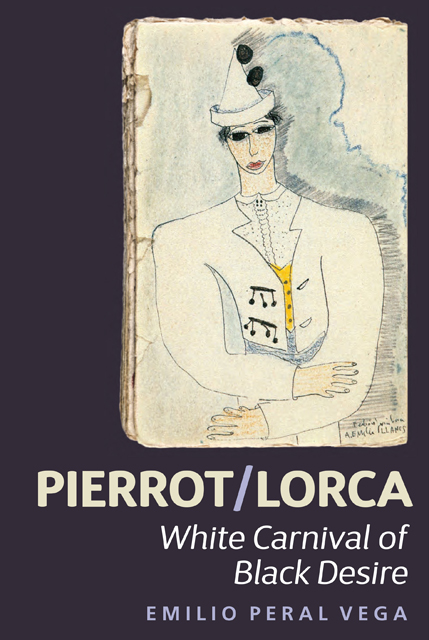

- Pierrot/LorcaWhite Carnival of Black Desire, pp. 11 - 30Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2015