Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Prologue

- 1 A Modern Mask: From Deburau to The Tramp

- 2 First Examples of an Effeminate Pierrot: From Verlaine to Lorca

- 3 Pierrot/Lorca: Alter Ego for a Young Poet

- 4 Lorca/Pierrot: Between Painting and Theatre

- 5 Love Game and Masquerade: Dalí/Lorca

- 6 Perlimplín/Lorca/Pierrot: Frustrated Desire

- 7 A White Clown for a Black Desire: El público and Así que pasen cinco años

- Epilogue

- Bibliography

- Index

5 - Love Game and Masquerade: Dalí/Lorca

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 22 February 2023

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Prologue

- 1 A Modern Mask: From Deburau to The Tramp

- 2 First Examples of an Effeminate Pierrot: From Verlaine to Lorca

- 3 Pierrot/Lorca: Alter Ego for a Young Poet

- 4 Lorca/Pierrot: Between Painting and Theatre

- 5 Love Game and Masquerade: Dalí/Lorca

- 6 Perlimplín/Lorca/Pierrot: Frustrated Desire

- 7 A White Clown for a Black Desire: El público and Así que pasen cinco años

- Epilogue

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

It is not the intention of this chapter to present the conclusions regarding the eternally enigmatic relationship between Federico García Lorca and Salvador Dalí at which academia has arrived in recent decades, conclusions which, while not definitive, are at the very least enormously convincing. I will gloss over the detailed account of the friendship between Dalí and Lorca provided by Ian Gibson in his comprehensive Lorca-Dalí. El amor que no pudo ser (1999), and the work of many other first-rate scholars in many different fields of knowledge. To name but a few, I would highlight the work of Antonina Rodrigo (1981), Rafael Santos Torroella (1992a), Agustín Sánchez Vidal (1988a) and María Teresa García-Abad García (2005). Instead I will focus, more specifically, on the literary and pictorial expressions that directly, or indirectly, explore the relationship between the poet and the painter by means of imagery drawn from commedia dell’arte, and on how from this starting point we may open new avenues towards understanding the devotion they professed towards one another.

El paseo de Buster Keaton (1925) was conceived by Lorca during the summer of 1925 in Granada. The genesis of this dialogue is very different to that of the previous works since, as Ian Gibson points out, Lorca had returned from Cadaqués ‘enamorado de Dalí’ (2004: 138). Gibson indicates that for Dalí ‘la situación debe de resultar muy difícil, pues, si bien se siente muy halagado por las atenciones del poeta, se resiste tenazmente a admitir la posibilidad de ser homosexual él mismo, ode tener siquiera leves inclinaciones homosexuales, y quizá teme que, si la relación se hace más íntima, corre el peligro de sucumbir’ (2004: 138). Thus, it is not strange that El paseo de Buster Keaton, in its apparent innocence, is one of the first reflections of sexual anxiety in Lorca, to the point that, in the words of Carlos Jerez-Farrán, ‘la pieza en realidad es una autodramatización de los problemas íntimos que por esos años atenazaban al autor’ (1997: 630). Indeed, this brief dialogue, ‘de un hermetismo y una intensidad semiótica casi impenetrable’ (Jerez-Farrán 1997: 630), illustrates some of Lorca’s obsessions with regard to his sexuality.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

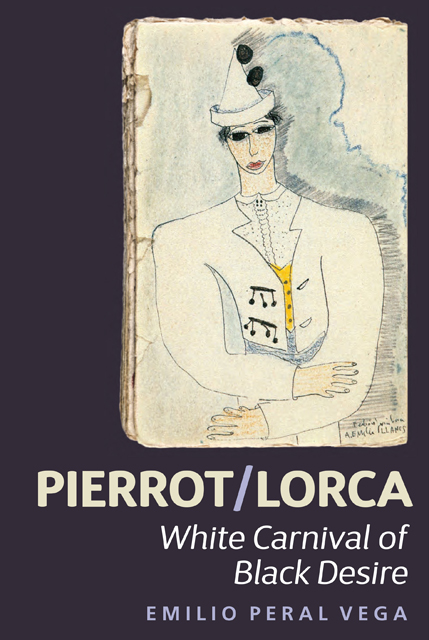

- Pierrot/LorcaWhite Carnival of Black Desire, pp. 77 - 94Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2015