Chapter 4 - Unstuck in Time. or: the Sudden Presence of The Past

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 15 January 2021

Summary

If you could lick my heart, it would poison you.

Yitzhak (Ante) Zuckermann,

second in command during the Warsaw Ghetto

uprising (1944) in the film Shoah (1985)

From history to memory

Since 1989, the past is no longer what it used to be, and neither is the academic study of the past – that is the Geschichtswissenschaft. No historian had predicted the total collapse of the Soviet bloc and the sudden end of the Cold War, the ensuing German unification and the radical reshuffling of global power relations. A similar story goes for the other two ‘epochal’ and ‘rupturing’ events of the past two decades: ‘9/11’ and the economic meltdown of 2008. Therefore, academic historians can claim very little credit for their traditional role as the privileged interpreters of the present in its relationship to the past and the future (and it is only a small consolation to know that the social scientists and the economists performed only slightly better on this score).

Maybe even more surprising – or disappointing – is the observation that no historian had imagined the eruptions of the past into the present which started in Eastern-Central Europe directly after 1989 – especially in the form of genocidal war and of ethnic cleansing in former Yugoslavia. Suddenly it seemed like the Croats and the Serbs had slipped back into the Second World War.

Through these events both the ‘pastness of the past’ (which had been the constitutive presupposition of academic history since the French revolution) and the capacity of academic history to explain how the past is connected to the present, suddenly lost their ‘evidential’ quality. If burying the dead is equal to creating the past, as Michel de Certeau and Eelco Runia both have argued, their funeral was suddenly interrupted, confronting historians since 1989 with a ‘haunting’ past instead of with a – distant – ‘historical’ past. This change can undoubtedly be connected to an experience of crisis, as Jan-Werner Müller has recently suggested: ‘According to John Keane, “crisis periods …. prompt awareness of the crucial importance of the past for the present. As a rule, crises are times during which the living do battle for the hearts, minds and souls of the dead”.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

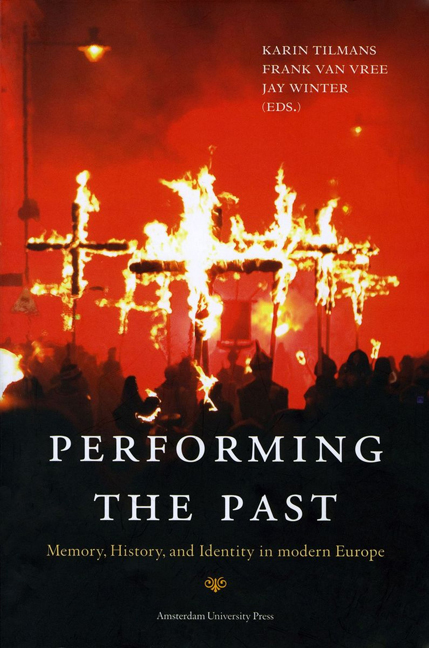

- Performing the PastMemory, History, and Identity in Modern Europe, pp. 67 - 102Publisher: Amsterdam University PressPrint publication year: 2012