Chapter 11 - Novels and Their Readers, Memories and their Social Frameworks

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 15 January 2021

Summary

This chapter focuses on literature and the reading act as a nodal point, a relay station, in the dissemination (in space) and transmission (across generations) of cultural memory. In doing so, it draws attention to three interrelated problem areas: 1) the currency of literature is principally shaped by the language of its expression, whereas the currency of memories is principally shaped in societal or political frameworks; 2) the social and political frameworks (i.e. states and institutions) in which cultural memories are current can be less durable and more fluid than the canonicity of certain literary texts; 3) the literary evocation of identity is not just a matter of straightforward transgenerational perpetuation, but forms part of a complex self/other dialectics. These issues are traced with reference to the case of literary historicism from the Flemish (as opposed to Dutch) historical novel.

Private reading, social memory, imagined community

In 1920, Ernest Claes (1885-1968) published De Witte, a Tom Sawyer-style novel destined to become one of the perennial sellers of Netherlandic literature. It reached its 100th reprint in 1962 (it is now in its 126th). A statue to the author was erected in his birthplace in the 1960s; the book was filmed twice (in 1934 and 1980) and a television series based on its setting and on Claes's other works (Wij Heren van Zichem, 1968-1969) became a benchmark in Flemish broadcasting.

The book describes the rebellious pranks of a boy, the eponymous ‘Whitey’ (so named after the colour of his hair and based loosely on Claes himself and on a fellow villager), and is set in the poor agricultural east of Flemish-speaking Belgium. The frugal traditionalism of its peasant setting is evoked with whimsy, sentimental nostalgia, and melancholy. In the course of the book, the boy escapes his peasant background and its harsh authority figures (father, schoolteacher) by a mixture of waywardness and a lively literary imagination (as did Claes himself). The turning point in his pre-adolescent life is his reading of another perennial classic of Flemish letters, Hendrik Conscience's De Leeuw van Vlaenderen (The Lion of Flanders, 1838). The chapter thematizing this experience is, typically, a mixture of broad humour and wistful empathy. Whitey is punished, once again, by the choleric, violent schoolteacher, and locked up in a storeroom containing books.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

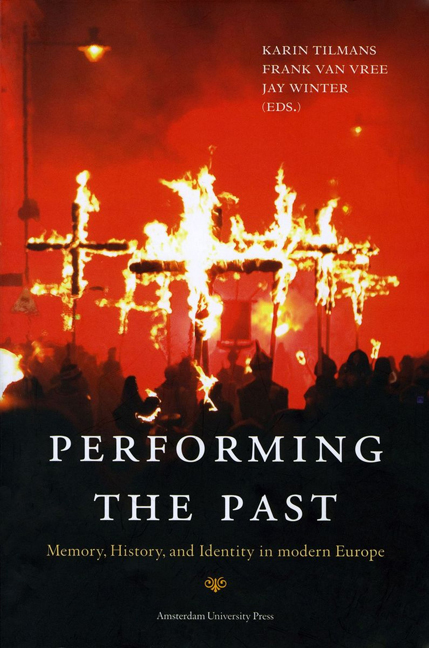

- Performing the PastMemory, History, and Identity in Modern Europe, pp. 235 - 256Publisher: Amsterdam University PressPrint publication year: 2012