The Latin alphabet inherited from its Etruscan model a superfluity of signs to represent the phoneme /k/: <c>, <k> and <q>. It also inherited, to some extent, the convention in early Etruscan inscriptions whereby <k> was used in front of <a>, <q> before <u>, and <c> before <e> and <i>, although consistent usage of this pattern is found rarely even in the oldest Latin inscriptions (Reference HartmannHartmann 2005: 424–5; Reference Wallace and ClacksonWallace 2011: 11; Reference Sarullo, Moncunill Martí and Ramírez-SánchezSarullo 2021). Over time, <c> was preferred for /k/ in all positions, while the digraph <qu> was used to represent the phoneme /kw/. Nonetheless, both <k> before <a> and <q> before <u> (with the value /k/) lived on as optional spellings into the imperial period.

Since the writers on language often mentioned <k> and <q> together, I compile here their comments for both usages (organised in rough chronological order). Especially as regards the use of <k> there is considerable variation between the authors, and the discussion continued past the fourth century AD. Consequently, I have included some writers from later than the fourth century, without carrying out a complete survey. I will refer back to these in the separate discussions of <k> and <q> below.

q littera tunc recte ponitur, cum illi statim u littera et alia quaelibet una pluresque uocales coniunctae fuerint, ita ut una syllaba fiat: cetera per c scribuntur.

The letter q, then, is rightly used when a u follows it directly and then one or more vowels are joined to it, such as to make a single syllable: other contexts require use of c.

alia sunt quae per duo u scribuntur, quibus numerus quoque syllabarum crescit. similis enim uocalis uocali adiuncta non solum non cohaeret, sed etiam syllabam auget, ut ‘uacuus’, ‘ingenuus’, ‘occiduus’, ‘exiguus’. eadem diuisio uocalium in uerbis quoque est, <ut> ‘metuunt’, ‘statuunt’, ‘tribuunt’, ‘acuunt’. ergo hic quoque c littera non q apponenda est.

There are other words which are written with double u, whose number of syllables increases. Because a vowel attached to another same vowel not only does not form a single syllable, it even increases the number of syllables, as in uacuus, ingenuus, occiduus, exiguus. The same division of vowels also takes place in verbs, as in metuunt, statuunt, tribuunt, and acuunt. Therefore here too one should use the letter c not q.

an rursus aliae redundent, praeter illam adspirationis, quae si necessaria est, etiam contrariam sibi poscit, et k, quae et ipsa quorundam nominum nota est, et q, cuius similis effectu specieque, nisi quod paulum a nostris obliquatur, coppa apud Graecos nunc tantum in numero manet, et nostrarum ultima, qua tam carere potuimus quam psi non quaerimus?

Or again, do we not wonder whether some letters are redundant; aside from the letter of aspiration [i.e. h] – if this is necessary, there ought also to be one expressing lack of aspiration – also k, which by itself is an abbreviation of certain nouns, and q, which is similar in effect and appearance – apart from the fact that we have twisted it somewhat – to the Greek qoppa, which is only used as a number, and the last of our letters [i.e. x], which we could do without just as well as psi.

nam k quidem in nullis uerbis utendum puto nisi, quae significat etiam, ut sola ponatur. hoc eo non omisi, quod quidam eam, quotiens a sequatur, necessariam credunt, cum sit c littera, quae ad omnis uocalis uim suam perferat.

I think that k ought not be used in any words, except those for which it can also stand as an abbreviation on its own. I do not exempt from this rule use of k whenever a follows, which some people think is necessary, because the letter c can express its own sound regardless of what vowel follows.

hinc supersunt ex mutis ‘k’ [et c] et ‘q’, de quibus quaeritur an scribentibus sint necessariae. et qui ‘k’ expellunt, notam dicunt esse magis quam litteram, qua significamus ‘kalumniam’, ‘kaput’, ‘kalendas’: hac eadem nomen ‘Kaeso’ notatur. … at qui illam esse litteram defendunt, necessariam putant iis nominibus quae cum ‘a’ sonante ha[n]c littera[m] inchoant. unde etiam religiosi quidam epistulis subscribunt ‘karissime’ per ‘k’ et ‘a’.

Of the stops, k and q remain, about which people wonder whether they are necessary for writers. Those who remove k say that is more a sort of symbol than a letter, which we use to represent kalumnia, kaput, kalendae: it is also used for the name Kaeso … But those who defend k being a letter think it necessary in words which begin with this letter pronounced along with a. As result, certain punctilious writers even write karissime in the greetings in their letters with k and a.

‘locutionem’ quoque Antonius Rufus per ‘q’ dicit esse scribendam, quod sit ab eo est ‘loqui’; item ‘periculum’ et ‘ferculum’. quae nomina contenta esse ‘c’ littera existimo …

Antonius Rufus says that locutio ought to be written with ‘q’, because it comes from loqui; likewise periculum and ferculum. I think the words are content to be written with ‘c’ …

‘k’ quidam superuacuam esse litteram iudicauerunt, quoniam uice illius fungi satis ‘c’ posset, sed retenta est, ut quidam putant, quoniam notas quasdam significant, ut Kaesonem et kaput et kalumniam et kalendas. hac tamen antiqui in conexione syllabarum ibi tantum utebantur ubi ‘a’ littera subiugenda erat, quoniam multis uocalibus instantibus quotiens id uerbum scribendum erat, in quo retinere hae litterae nomen suum possent, singulae pro syllaba scribebantur, tanquam satis eam ipso nomine explerent … ita et quotiens ‘canus’ et ‘carus’ scribendum erat, quia singulis litteris primae syllabae notabantur, ‘k’ prima ponebatur, quae suo nomine ‘a’ continebat, quia si ‘c’ posuissent ‘cenus’ et ‘cerus’ futurum erat, non ‘canus’ et ‘carus’.

Certain people judge k to be redundant, since c can discharge its duty well enough, but it is retained, others think, since it acts as a symbol for certain words, such as Kaeso and kaput and kalumnia and kalendae. When forming syllables, however, the ancients only used it when the letter a was added to it, since whenever a word containing many vowels had to be written, in which these letters could, as it were, represent their own name, these letters on their own were used to express an entire syllable, as though they fulfilled its sound enough by their name … Thus, too, whenever canus and carus were to be written, because they wrote the first syllable with a single letter, they used to put k at the beginning, which contained a in its name, because if they had put c there the words would have been cenus and cerus rather than canus and carus.

‘k’ perspicuum est littera quod uacare possit, et ‘q’ similis. namque eadem uis in utraque est, quia qui locus est primitus unde exoritur ‘c’, quascumque deinceps libeat iugare uoces, mutare necesse est sonitum quidem supremum, refert nihilum, ‘k’ prior an ‘q’ siet an ‘c’.

Clearly k is a letter which could be considered useless, and likewise q. They both have the same value, because, regardless of whatever vowel follows them, the place where they begin their pronunciation is also where c is made; it is only this following vowel which makes them sound different, and it makes no difference whether one writes k, q or c before it.Footnote 1

‘k’, similiter otiosa ceteris sermonibus, tunc in usu est, cum ‘kalendas’ adnotamus <aut> ‘kaput’, saepe ‘Kaesones’ notabant hac uetusti littera.

K, which is likewise unnecessary in other words, is, however, used when we write kalendae or kaput; old writers spelt Kaesones with this letter.

ex his superuacuae quibusdam uidentur k et q; qui nesciunt, quotiens a sequitur, k litteram praeponendam esse, non c; quotiens u sequitur, per q, non per c scribendum.

Of these [stops] some people think that k and q are redundant; they do not know that whenever a follows, k ought to be put before it, not c, and whenever u follows, q should be written, not c.

k autem dicitur monophonos, quia nulli uocali iungitur nisi soli a breui, et hoc ita ut ab ea pars orationis incipiat; aliter autem non recte scribitur.

But k is called monophonos, because it cannot be used before any vowel other than short a, and even then only at the start of a word; otherwise it is wrong to use it.

attamen ‘locutus, secutus’ per c, quamuis quidam praecipiant ad originem debere referri, quia est ‘locutus’ a loquendo, ‘secutus’ a sequendo, <et ideo> per q potius quam per c haec scribenda. nam ‘concussus’ quamuis a ‘quatio’ habeat originem et ‘cocus’ a coquendo et ‘cotidie’ a quoto die et ‘incola’ ab inquilino, attamen per c quam per q scribuntur.

But locutus and secutus ought to be spelt with c, even though some people teach that they should be spelt with q rather than with c, with an eye to their origin, because locutus comes from loqui, and secutus from sequi. This is because, although concussus comes from quatio, and cocus from coquere and cotidie from quotus dies and incola from inquilinus, nonetheless these words are all written with c rather than q.

praeponitur autem k quotiens a sequitur, ut kalendae Karthago.

But k is used whenever a follows, as in kalendae or Karthago.

k littera notae tantum causa ponitur, cum kalendas solas aut Kaesonem aut kaput aut kalumniam aut Karthaginem scribimus.

The letter k is only used as an abbreviation, when it only represents kalendae or Kaeso or kaput or kalumnia or Karthago.

superuacuae uidentur k et q, quod c littera harum locum possit implere; sed inuenimus in Kalendis et in quibusdam similibus nominibus, quod k necessario scribitur.

k and q seem to be superfluous, because the letter c can be used in their place. But we find, in kalendae and certain similar words, that it is necessary to write k.

k littera notae tantum causa ponitur, cum calumniam aut clades aut Caesonem quaqua aut caput significat. k consonans muta superuacua, qua utimur, quando a correpta sequitur, ut Kalendae kaput kalumniae.

The letter k is only used as a symbol when it represents calumnia, or clades, or Caeso (always), or caput. K the plosive consonant is completely redundant, which we use when a short a follows, as in kalendae, kaput, kalumnia.

k littera consonans muta notae tantum causa ponitur, cum aut kalendas sola significat, aut Kaesonem, aut kaput aut kalumniam aut Karthaginem.

The letter k is a plosive consonant which is only used as an abbreviation, when on its own it represents kalendae or Kaeso or kaput or kalumnia or Karthago.

nunc et in his mutis superuacue quibusdam k et q litterae positae esse uidentur, quod dicant c litteram earundem locum posse complere, ut puta Carthago pro Karthago. nunc hoc uitium etsi ferendum puto, attamen pro quam quis est qui sustineat cuam? et ideo non recte hae litterae quibusdam superuacuae constitutae esse uidentur.

Now, among these stops k and q are included, although to some they seem to be superfluous, because they say that the letter c could take their place: think of Carthago for Karthago. Now, I think that this fault – even if it is one – should be put up with, because who could bear cuam instead of quam? So these letters seem to me to have been wrongly characterised as superfluous by those people.

k non scribitur nisi ante a litteram puram in principio nominum vel cuiuslibet partis orationis, cum sequentis syllabae consonans principium sit, sicut docui in libro primo.

K is not used except before a on its own, at the start of nouns or any part of speech, when the following syllable starts with a consonant, as I have taught in my first book.

k littera non scribitur, nisi a littera in principiis nominum uel uerborum consequentis syllabae et consonans principium sit, sicut in institutis artium, hoc est in libro primo, monstraui, Kamenae kaleo.

The letter k is not used, unless with the letter a at the start of nouns or verbs, and a consonant begins the following syllable, just as I demonstrated in the Instituta artium, my first book: Kamenae, kaleo.

k uero et q aliter nos utimur, aliter usi sunt maiores nostri. namque illi, quotienscumque a sequebatur, k praeponebant in omni parte orationis, ut kaput et similia; nos uero non usurpamus k litteram nisi in Kalendarum nomine scribendo. itemque illi q praeponebant, quotiens u sequebatur, ut qum; nos uero non possumus q praeponere, nisi et u sequatur et post ipsam alia uocalis, ut quoniam.

We use k and q differently from our ancestors. They, whenever a followed, put k before it in every part of speech, as in kaput and similar words; but we do not employ the letter k except when we write kalendae. Likewise, they used to put q before a following u, as in qum; but we cannot use q except when u follows and is itself followed by another vowel, as in quoniam.

k et q: apud ueteres haec erat orthographia, ut, quotiens a sequeretur, k esset praeposita, ut kaput Kalendae; quotiens u, q. sed usus noster mutauit praeceptum, et earum uicem c littera implet.

K and q: the ancients used to include this in their spelling practice, so that whenever a followed, k was placed before it, as in kaput, kalendae, and whenever u followed, q was used. But our usage changed the rule, and the letter c took their place.

quae ex his superuacuae uidentur? k et q. quare superuacuae? quia c littera harum locum possit explere. uerum has quoque necessarias orthographiae ratio efficit. nam quotiens a sequitur, per k scribendum est, ut kanna, kalendae, kaput; quotiens u, per q, ut quoniam Quirites; quotiens reliquae uocales, per c, ut certus, ciuis, commodus.

Which of these [stops] seem redundant? K and q. Why redundant? Because the letter c can take their place. But orthographic logic makes these also necessary. Because whenever a follows, the stop should be written with k, as in kanna, kalendae, kaput; whenever u follows, it should be written with q, as in quoniam, Quirites; whenever the remaining vowels, with c, as in certus, ciuis, commodus.

<k> before /a(ː)/

Modern scholars usually say that in the imperial period, K. was the standard abbreviation for the praenomen Caeso (C. being used for Gaius), and the usual spelling of kalendae was with a <k>.Footnote 3 It is often noted that Carthago, Carthaginiensis was frequently spelt with a <k>,Footnote 4 which could also act as an abbreviation for this and for other words. Other words are occasionally mentioned in which <k> is used before /a/.Footnote 5

The writers on language have an unusually broad and complex range of views about use of <k> (for the relevant passages, see pp. 138–43). Until the fourth century it seems likely that its use, at least in some contexts, was not uniformly seen as old-fashioned. Quintilian, the only one who says that he believes <k> should not be used (except in words for which it can stand alone as an abbreviation), accepts that others maintain that it should be used whenever <a> follows, as does Velius Longus (who, however, suggests its use is pedantic). Most of the writers say it should be used, either whenever followed by <a> (Donatus, Charisius, Maximus Victorinus), short /a/ (Diomedes),Footnote 6 short /a/ at the start of a word (Marius Victorinus) or short <a> at the start of a word when the following syllable begins with a single consonant (Ps-Probus). Terentianus Maurus only gives the examples of kalendae and kaput, along with Kaesōnēs in older writers. Even in those authors who do not restrict its use to the beginning of a word, this may be implicit, since all the examples are in fact at the start of a word.

Terentius Scaurus is the only writer prior to the fifth century not to mention use of <k> in full words: he states that some deny it altogether, and that there are others who approve it only as an abbreviation. Servius and Cledonius say that, while earlier writers used it whenever an <a> followed, now (in the fifth century) it is used only in kalendae. Use of <k> as an abbreviation is identified as representing Caesō, caput and calumnia (Charisius, Diomedes, Dositheus, Velius Longus, Terentius Scaurus), kalendae (Charisius, Dositheus, Velius Longus, Terentius Scaurus), Carthāgō (Charisius and Dositheus), and clādēs (Diomedes).

How does the information in the writers on language fit with the epigraphic record? First it is worth mentioning that <k> is also used to represent /k/ in proper nouns in two contexts which are not relevant to the present discussion; in both cases use of <k> is not restricted to position before /a(ː)/. The first group is Greek names, or Roman names which, however, appear in a highly ‘Greek’ context, such as bilingual inscriptions or inscriptions which contain other Greek names, for example:

Britanniae / Sanctae / p(osuit) Nikomedes / Augg(ustorum) nn(ostrorum) / libertus (CIL 7.232, York)

Quintio Ḳrassi / Frugi sumptuarius / Κοιντιων Κρασσου / Φρουγι σουμπτου/αριος (CIL 3.12285, Athens)

D(is) M(anibus) / L(ucio) Plautio Heli/o filio qui ui/xit annis duob/us mensibus / X diebus XII Iso/krates et Markel/la filio pientissi/mo fecerunt (CIL 6.24272, Rome).

The second group is non-Roman and non-Greek names, in which use of <k> may represent some sound different from the Latin /k/ written with <c>, or is felt to be appropriate to mark out ‘foreign’ names, for example:

Bodukus f(ecit) (AE 2002.885, Edgbaston)

D(is) M(anibus) / Galulircli / et omnes / an<t>ecessi / Duetil Tiblik / Eppimus Soris / omn(i)bus co(m)p/otoribus / bene (CIL 13.645, Bordeaux).

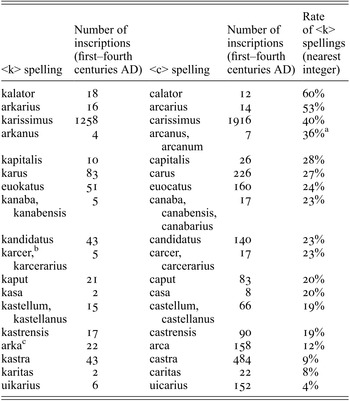

Outside these proper nouns, use of <k> overwhelmingly occurs before /a(ː)/,Footnote 7 and as a single letter stands as an abbreviation of a number of words (sometimes before other vowels). A large number of personal names that contain /ka(ː)/ are found spelt with <k>,Footnote 8 as well as the place name Carthāgō. Otherwise, the use of <k> appears to be lexically determined, with frequency varying significantly across lexemes, as can be seen in Table 14. The table contains all examples of words in which the <k> spellings appear at a rate greater than 1% in inscriptions dated from the first to fourth centuries AD which I found in the EDCS (except for kalendae, where <k> is standard, and words only found abbreviated as k.). I have not removed proper names where these seem originally to have been the same lexeme.Footnote 9

Table 14 Inscriptional spellings with <k> and <c>

| <k> spelling | Number of inscriptions (first–fourth centuries AD) | <c> spelling | Number of inscriptions (first–fourth centuries AD) | Rate of <k> spellings (nearest integer) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| kalator | 18 | calator | 12 | 60% |

| arkarius | 16 | arcarius | 14 | 53% |

| karissimus | 1258 | carissimus | 1916 | 40% |

| arkanus | 4 | arcanus, arcanum | 7 | 36%Footnote a |

| kapitalis | 10 | capitalis | 26 | 28% |

| karus | 83 | carus | 226 | 27% |

| euokatus | 51 | euocatus | 160 | 24% |

| kanaba, kanabensis | 5 | canaba, canabensis, canabarius | 17 | 23% |

| kandidatus | 43 | candidatus | 140 | 23% |

| karcer,Footnote b karcerarius | 5 | carcer, carcerarius | 17 | 23% |

| kaput | 21 | caput | 83 | 20% |

| kasa | 2 | casa | 8 | 20% |

| kastellum, kastellanus | 15 | castellum, castellanus | 66 | 19% |

| kastrensis | 17 | castrensis | 90 | 19% |

| arkaFootnote c | 22 | arca | 158 | 12% |

| kastra | 43 | castra | 484 | 9% |

| karitas | 2 | caritas | 22 | 8% |

| uikarius | 6 | uicarius | 152 | 4% |

a There appears to be a distinction in usage between arkanus, which appears only as a cult title of Jupiter and in the title Augustalis arkanus, while arcanus appears as a cognomen, an adjective or as the substantive arcanum.

b Including one instance of kark(eris) (AE 1983.48).

c The following strings produced some results (29/01/2021): ‘arkae’ (‘wrong spelling’, 9 inscriptions), ‘arkarum’ (‘wrong spelling’, 1 inscription), ‘arcam’ (68 inscriptions, and 1 containing ‘arkam’ not produced in the ‘wrong spelling’ search), ‘arcae’ (45 inscriptions, and 9 containing ‘arkae’ not produced in the ‘wrong spelling’ search), ‘arcarum’ (0 inscriptions, and 1 containing ‘arkarum’ not produced in the ‘wrong spelling’ search). I also searched for ‘ arca ’ (45) and ‘ arka ’ (1, after removing the example in IS 319) in ‘search original texts’ on 28/09/2022.

The most frequent word with <k> is kalator, which makes up 60% of all instances of this lexeme in inscriptions dated to the first–fourth centuries AD in the EDCS. By far the greatest number of tokens of a word spelt with <k> are found for carissimus ‘dearest’, and it also has a high frequency relative to spellings with <c>: a search for karissimus on the EDCS finds 1258 inscriptions containing this spelling beside 1916 with carissimus in the first to fourth century AD, a frequency of 40%. The adjective from which it is derived, carus ‘dear’, is also common (though far less so than carissimus), especially as a name, and shows a somewhat lower frequency of <k> spellings, at 27%.Footnote 10 However, the derived noun karitas is found only in 2 inscriptions, with caritas and Caritas in 22 in the same period (8%), while the extremely numerous causa is, as far as I can tell, never spelt kausa after the start of the first century AD;Footnote 11 for many words, there are no spellings with <k> at all.

The relatively high numbers and frequency of <k> in these lexemes compare with the more haphazard occasional uses of <k> in other words. The forms dedicauit, dedicauerunt, dedicatus appear in 1246 inscriptions compared to 6 for dedikauit, dedikauerunt, dedikatus (0.5%); there are single examples of kalumnia,Footnote 12 kapsarius,Footnote 13 kasus,Footnote 14 kanalicularius ‘a clerk in the Roman army’Footnote 15 and katolika (ILCV 1259, probably under the influence of Greek orthography).

As an abbreviation, <k> can stand for cardo ‘baseline (in surveying)’, which never appears written in full and is found 11 times in inscriptions dated to the first to fourth century AD, and in fact 49 times across all inscriptions regardless of period.Footnote 16 It also often stands for castra and castrensis, for caput, and for casa in 3 inscriptions (2 of which are undated in the EDCS). Twice in the same inscription we find b. k. for bona caduca (Reference IhmIhm 1899: 141). The abbreviation k. c. for cognita causa appears in two inscriptions from Ostia (CIL 14.4499, 5000), and ḳ. k. once (AE 2003.703c = 2016.468) for citra cardinem.Footnote 17 These cases where it stands as an abbreviation of a word where /k/ is followed by a vowel other than /a(ː)/ are surprising, but perhaps connected to the fact that in each case they form a syntagm of two consecutive words beginning with /k/. There is a single instance of kos for consulibus (CIL 6.2120). In CIL 5.1025, the abbreviation k(oniugi) is directly followed by karissime.

The use of <k> in inscriptions to some extent matches what the writers on language say, but shows somewhat different applications. As many state, it is uniformly found before /a(ː)/ (except in abbreviations), but Diomedes, Marius Victorinus and Ps-Probus’ further restriction to short /a/ is not followed, since we find <k> before /aː/ in arcānus, arcārius, cārissimus, cāritās, cārus, euocātus, uicārius. The range of words written with <k> is greater than those given as examples by the writers, but they do not say that their examples are exhaustive (although the repetition of the same examples through the tradition might imply this); there are also examples of <k> in non-initial position, again unlike the examples, and against the explicit advice of Marius Victorinus and Ps-Probus. Likewise, <k> can stand as an abbreviation for caput, but also a wider range of words than implied by the writers, who do not mention <k> for castra and cardo despite their appearance in relatively large numbers (perhaps because the language of the army and of surveying fell outside the literary focus of the writers).

Since I have carried out searches for individual lexemes it is not possible to see to what extent spellings with <k> in the inscriptions reflect an orthographic practice of writing every word containing the sequence /ka(ː)/ with <k>, rather than only writing particular words with <k>. However, the very fact that frequency of spelling with <k> is so variable across lexemes implies that many of those using <k> some of the time did not do so in every context, as some of the grammarians imply is (or should be) the case. In particular, the high frequency of <k> in the word cārissimus (very heavily concentrated in funerary inscriptions) suggests that it was not solely the ‘religiosi’ who were using it in this lexeme, as Velius Longus states (nor was it restricted to letters).

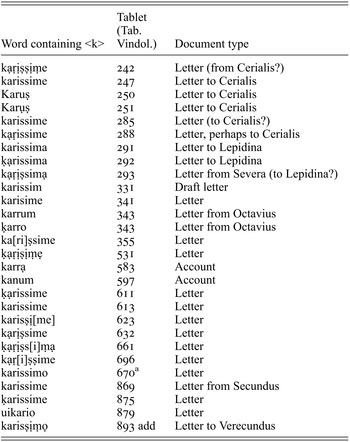

We can now move on to the evidence of the sub-elite corpora, beginning with the instances of <k> at Vindolanda (Table 15).Footnote 18 The lexeme karissimus, karissime clearly predominates, mostly appearing in the closing greeting of letters, occasionally in the opening greeting (Tab. Vindol. 670, 893 add.), and once in the main text (331). The closing formula is often written in a second hand, presumably that of the author: these are 242 (probably the prefect Cerialis), 247, 285, 623 (Aelius Brocchus, an equestrian officer), 291, 292, 293 (Severa, wife of Aelius Brocchus), 611 (Haterius Nepos, an equestrian, probably a prefect), 613 (unknown), 869 (a Secundus), 875 (unknown). So, many of these instances of <k> are in parts of texts that are not written by scribes. There is no evidence as to whether the instances of karissimus, -e in closing greetings reflect scribal orthography or not in some letters. 341 and 531 preserve only the closing greeting; on 355 the editors comment ‘it is not clear whether the hand changes for the last two lines’. In 632 and 661 the same hand writes the final greeting and the rest of the letter. There are only two other instances of /ka(ː)/ written by the same hands in these letters; 632 also includes the word caballi, while 670 has Cataracṭoni. In 613 the other hand writes capitis, and in 875 Candịḍị, C̣ạ[, Carạṇṭ[.

Table 15 <k> spellings in the Vindolanda tablets

| Word containing <k> | Tablet (Tab. Vindol.) | Document type |

|---|---|---|

| kạṛịṣṣịṃe | 242 | Letter (from Cerialis?) |

| karissime | 247 | Letter to Cerialis |

| Karuṣ | 250 | Letter to Cerialis |

| Karụṣ | 251 | Letter to Cerialis |

| karissime | 285 | Letter (to Cerialis?) |

| kạṛissime | 288 | Letter, perhaps to Cerialis |

| karissima | 291 | Letter to Lepidina |

| ḳạrissima | 292 | Letter to Lepidina |

| kạṛịṣsimạ | 293 | Letter from Severa (to Lepidina?) |

| karissim | 331 | Draft letter |

| karisime | 341 | Letter |

| karrum | 343 | Letter from Octavius |

| ḳarro | 343 | Letter from Octavius |

| ka[ri]ṣsime | 355 | Letter |

| ḳạṛịṣịṃẹ | 531 | Letter |

| karrạ | 583 | Account |

| kanum | 597 | Account |

| ḳạrissime | 611 | Letter |

| karissime | 613 | Letter |

| karisṣị[me] | 623 | Letter |

| kạrịṣsime | 632 | Letter |

| ḳạṛịṣs[i]ṃạ | 661 | Letter |

| kạṛ[i]ṣṣime | 696 | Letter |

| karissimo | 670Footnote a | Letter |

| karissime | 869 | Letter from Secundus |

| ḳarissime | 875 | Letter |

| uikario | 879 | Letter |

| karisṣịṃọ | 893 add | Letter to Verecundus |

a 670 is probably from the late second century AD, significantly later than the other tablets.

In the main, the hands which use <k> in this lexeme otherwise use standard spelling (as far as we can tell, since often there is little other text), as we might expect since several are of equestrian rank. In 292 Severa writes ma for mea (which could be a reduced form of the possessive pronoun or dittography after anima; Reference AdamsAdams 1995: 120). In 341 and 531 the geminate seems to be simplified in karisime for karissime, but there is not enough remaining text in either case to tell if this is a feature of these writers. In 661, we perhaps find a substandard spelling if muḍetur is for mundētur, although the editors are uncertain of the reading.Footnote 19

The remaining four letters have <k> in other contexts: in 250 and 251, Karus is the cognomen of the author, probably also a prefect; the letters are in different hands, and there is no reason to think either is his. There is no other instance of /ka(ː)/. The spelling of 250 is standard except for ḍebetorem for debitōrem ‘debtor’; given the general infrequency of i and e confusion at Vindolanda, Reference AdamsAdams (1995: 91) suggests the influence of debet, which seems possible.Footnote 20 343 is the letter sent to Vindolanda from Octavius, who may have been a civilian, and whose spelling has both substandard and old-fashioned features. Apart from karrum and ḳarro (and K(alendas)), /ka(ː)/ is otherwise spelt <ca> in Candido, explicabo, spịcas, circa, erubescam, and Cataractonio. 879 has uikario in a highly broken context: the spelling is otherwise standard, but there is little text, and no other instances of /ka(ː)/. In the accounts 583 and 597 there are no other instances of /ka(ː)/ (except for K(alendis) in the former). 597 shows a substandard spelling in the form of laṃṇis for laminīs ‘sheets’ and pestlus and p̣eṣṭḷ[us] for pessulus ‘bolt’ (Reference AdamsAdams 2003: 539–41).

The pattern of <k> use at Vindolanda appears pretty much as we might expect on the basis of the inscriptional evidence. Although strictly speaking we usually do not have evidence that writers who spell cārus, cārissimus with a <k> do not use <k> consistently before /a(ː)/, the match with the inscriptional evidence (and that of Velius Longus) suggests that this spelling is probably specific to this lexeme (there are only 2 examples spelt with <c>, at 255 and 306). We also find uicārius attested with <k> in the inscriptions (although not very frequently); there are no other examples at Vindolanda. The 3 instances across 2 tablets of karrum ‘wagon’ compare to 4 across 3 tablets of carrum (488, 642, 649), 4 across 3 tablets of carrulum (315, 316, 643), 1 of carrārius (309) and 1 of c̣arr[(721). There are no other instances of canis. Apart from in cārus, cārissimus, then, <k> is rare in the tablets: I count 139 instances of <ca>, of which 90 are word-initial, across a great range of lexemes, including castra (3 instances, tablets 300, 668) and castrēnsis (337), castellus (178), caput (613), casula (643), and personal names such as Candidus, Cassius and Caecilius.

As we will see in the case of <xs>, use of <k> does not provide as much evidence for a specific old-fashioned orthographic tradition among the scribes of Vindolanda as might be thought at first sight. In cārus, cārissimus, use of <k> is clearly standard in the greeting formulas of letters among writers of equestrian rank, including Severa, whose education was presumably not carried out in the army, as it is among scribes, if the letters all in one hand were written by them. Octavius, whose letter is apparently in his own hand, who is particularly fond of old-fashioned features, and who may or may not have received an army education, uses 2 out of 5 of the remaining instances of <k>. It is also conceivable that the use of <k> particularly in carrum may reflect this word’s Celtic origins, since <k> was in general associated with foreign words: the writers at Vindolanda were clearly in contact with Celtic speakers, so may have recognised it as a borrowing.Footnote 21

The other, much smaller, military corpora, show a different picture. There are 20 instances of <ca> at Vindonissa, including 2 examples of carus (both T. Vindon. 45) and castra (4, 40), and none of <ka>. At Bu Njem, there are 24 of <ca>, including once caṣtṛị[s (O. BuNjem 29), of which 5 are the lexemes camellus ‘camel’, camellārius ‘camel driver’ (3, 5, 10, 42, 78); all 6 examples of <k> are kamellus (8, 9) and kamellarius (7, 8, 76, 77). The preponderance of <k> in these words is probably because of their Greek origin. At Dura Europos, again, <k> is almost entirely lacking. Against 69 instances of <ca>, we find once Kastello (P. Dura 94, c. AD 240) as part of a place name (otherwise spelt with <c> several times) in a summary of dispositions of soldiers and once ]kas(tra?) (P. Dura 66SS/CEL 191.45, AD 216) in a letter. Both of these are lexemes which we saw occasionally receive the <k> spelling in the epigraphy more generally. Several letters in a military or official context from Egypt also use <k> in spelling kastra (CEL 207, AD 200–250), kastresia, kastrense (CEL 205, AD 220) or as an abbreviation for castrī (CEL 231, AD 395; 232, AD 396; 233, AD 401).Footnote 22 This may be a military convention which developed after the time of the Vindolanda tablets. In addition there is 1 instance of kapitum (CEL 234, 399).

The letters also match those of Vindolanda in showing use of <k> in cārissimus, which is used by writers of low and high educational level. 3 of the 4 instances of karissimus come from initial or final greetings formulas as at Vindolanda. 2 occur in the letters of Rustius Barbarus (k[a]ṛịṣṣịṃẹ CEL 74, karisimo CEL 77), which is interesting since he otherwise appears not to know any old-fashioned spellings and his orthography is highly substandard (pp. 35–6). The remaining 2 examples, both also from Egypt, are karissiṃe (CEL 140, AD 103, copy of an official letter from the praefectus Aegypti), and karissi[mum (CEL 177, AD 150–200, a military letter of commendation).

In the Claudius Tiberianus archive, only the scribe of one letter (P. Mich. VIII 467/CEL 141) uses <ka>, and does so inconsistently, with no particular rationale emerging: all 4 examples are word-initial, but the same is true of 1 out of 3 of the instances of <ca>; 2 instances consist of karus (in the main text) and karissimus (in the initial greeting formula), as we might expect, and <k> in Kalaḅ[el] might be particularly likely in a foreign place name, but kasus is not commonly spelt with <k> in the inscriptions. This writer is characterised by another old-fashioned spelling in the form of <uo> for /wu/, and substandard spellings (see p. 263).

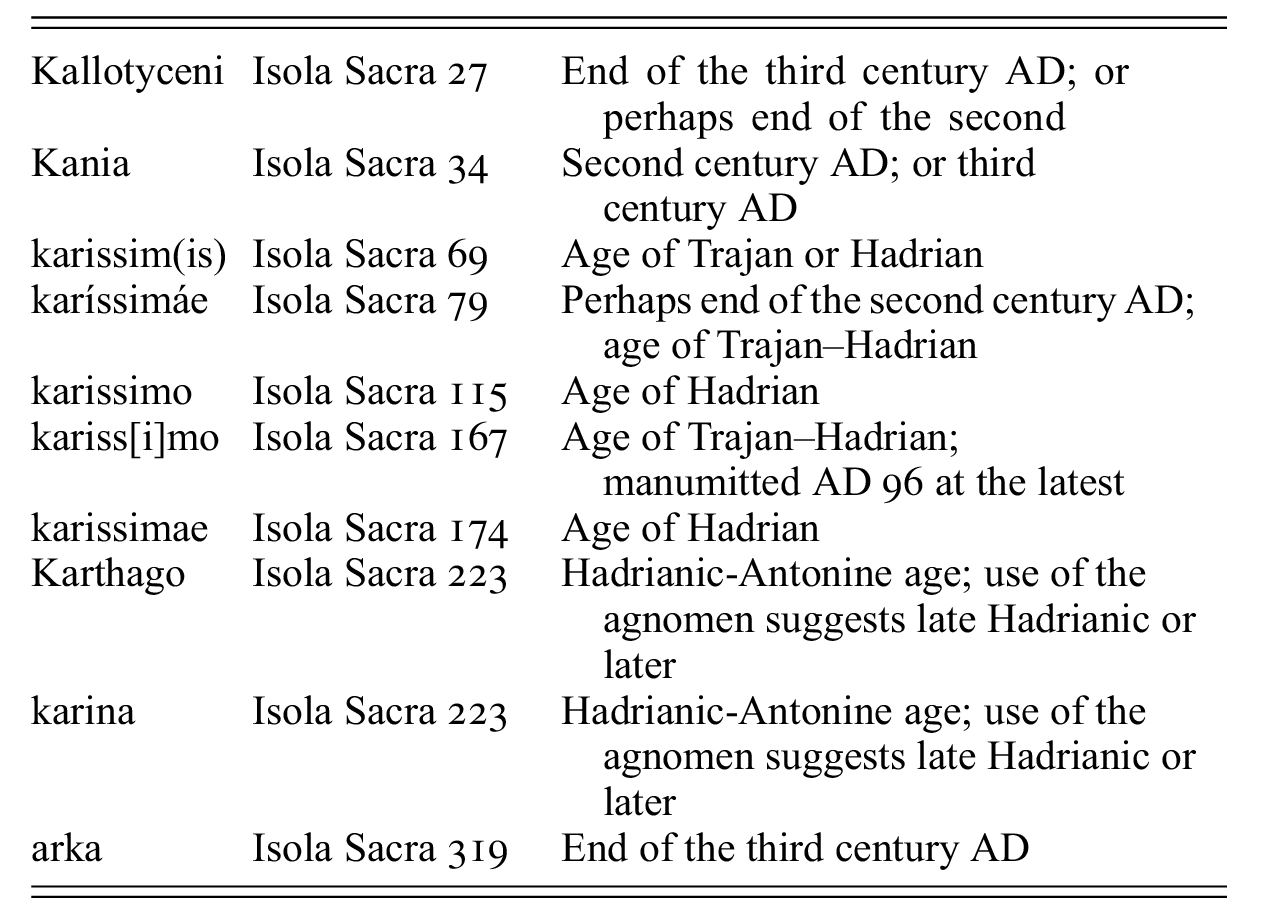

Table 16 shows the cases of <k> in the Isola Sacra inscriptions, with <k> once again predominantly used with the lexeme cārissimus, although less frequently than at Vindolanda (where we find 22 cases with <k> and only 2 with <c>) or in the epigraphy in general (where 40% of tokens of cārissimus have <k>). There are 5 instances of <k> in this word against 15 of <c>. Unlike at Vindolanda, the cognomen Cārus appears with <c>: Carae (IS 296). Otherwise, <k> appears in personal names (Kallotyceni, Kania),Footnote 23 the former of these Greek; but these are very much the minority: there are several dozen other names beginning with <ca>. Note in particular Callistianus (IS 85), Callityche (IS 133), Callisto twice, Callistion (IS 241), Callist[ (IS 282) and Canniae (IS 237). The single instance of <k> within the word is arka (IS 319), which has a <k> not infrequently in the epigraphy more generally. IS 223 has the only instance of a <k> spelling of carīna in all of Latin epigraphy (albeit compared to only three examples of carina), alongside the place name Karthago (but <c> is used in Caelestino). The use of <k> may be connected to the fact that the inscription includes a hexametric composition (and also includes the old-fashioned spelling lubens); its spelling is otherwise completely standard.

Table 16 <k> in the Isola Sacra inscriptions

| Kallotyceni | Isola Sacra 27 | End of the third century AD; or perhaps end of the second |

| Kania | Isola Sacra 34 | Second century AD; or third century AD |

| karissim(is) | Isola Sacra 69 | Age of Trajan or Hadrian |

| karíssimáe | Isola Sacra 79 | Perhaps end of the second century AD; age of Trajan–Hadrian |

| karissimo | Isola Sacra 115 | Age of Hadrian |

| kariss[i]mo | Isola Sacra 167 | Age of Trajan–Hadrian; manumitted AD 96 at the latest |

| karissimae | Isola Sacra 174 | Age of Hadrian |

| Karthago | Isola Sacra 223 | Hadrianic-Antonine age; use of the agnomen suggests late Hadrianic or later |

| karina | Isola Sacra 223 | Hadrianic-Antonine age; use of the agnomen suggests late Hadrianic or later |

| arka | Isola Sacra 319 | End of the third century AD |

There is an interesting distinction between the use of <k> in cārissimus and in other words. As already mentioned, the context of 223 is poetic, while 27, 34 and 319 all show signs of substandard orthography: 27 has Terenteae for Terentiae, filis for filiīs, qit for quid, aeo for eō and sibe for sibi, as well as sarcofago rather than sarcophagō; 34 has mesibus for mēnsibus; and 319 has hypercorrect Lucipher for Lūcifer. Meanwhile, all the inscriptions with <k> in cārissimus have standard spelling. This pattern is not dissimilar from the situation at Vindolanda, where <k> is used in cārissimus by standard spellers, while in other words it is used by Octavius and the writer of Tab. Vindol. 597, whose spelling is substandard. This may imply that use of <k> before <a> is subject to some rather fine distinctions: in the word karissimus it is an acceptable and commonly used variant in standard orthography, but in other words it may have a poetic ring or be characteristic of substandard spellers.

The tablets from Pompeii and Herculaneum show complete avoidance of <k> before /a(ː)/, except for in kalendae, and its derivative kalendarịọ (TH2 A13) ‘estate’. In TH2 there are some 55 instances of <ca>, including 3 instances of Carum (2 in TH2 85, 1 in TH2 85 bis) as a personal name. In the Jucundus tablets there are approaching 200 instances of <ca>, almost all in personal names, and no instances of <k> (there are no instances of cārus or Cārus). In the tablets of the Sulpicii there are also large numbers of <ca>, including a handful of Cārus, while the only case of <k> is in Ḳ[innamo] (TPSulp. 62), where the use of <k> is presumably triggered by the Greek name.

In the curse tablets, use of <k> before /a(ː)/ is practically non-existent, compared to several hundred instances of <ca>. The only instance is Karkidoni (Kropp 11.1.1/37), from Carthage, which is presumably a foreign name; Greek letters are also used at the start of the tablet. There are a handful of cases of <k> before another letter: Greek influence must also be responsible for the spellings koue for quem and kommendo (11.2.1/32), also from Africa, and perhaps also for Klaudia (1.5.4/2, Pompeii), given that this woman’s cognomen is Elena; the divine name Niske (3.11/1) from fourth century AD Britain is presumably a case of <k> being used for a foreign name, although no similar explanation arises for Markellinum (3.2/45, Aquae Sulis, second or third century AD).

The graffiti from the Paedagogium contain 4 instances of <k>, 2 in the Greek word Nikainsis (297), Nikaẹnsis (332), and 2 in Kartha(giniensis) (322), Kart(haginiensis) (323); all perhaps from the reign of Septimius Severus. There are 10 other examples of <ca>. In the London tablets there are 16 instances of <ca>, including Caro as a personal name (WT 36) and castello (WT 39), and none of <ka>.

Use of <k> in the corpora depends very much on lexeme and genre. The word carissimus, which occurs frequently in fairly formulaic contexts in letters, is overwhelmingly spelt with <k>, in the letters at Vindolanda and elsewhere, in texts which show standard and substandard spelling, and which are written both by scribes and non-scribes, including those of relatively high and low social rank. The same lexeme is also spelt frequently with <k> in the Isola Sacra funeral inscriptions.

At Vindolanda, it is possible that carrum ‘wagon’ may also have become associated with a spelling <k>, although this may have been a peculiarity of individual writers rather than part of the scribal tradition in the army; as also perhaps in the very occasional other instances of use of <k>. The use of <k> in the word castra, and in particular as an abbreviation, seems to have been a feature of official/military spelling in Egypt and Dura Europos in the third–fifth centuries AD.

There is very little evidence for a general rule that <k> should be used before all instances of /a(ː)/, although perhaps the writer of one of the letters of Claudius Tiberianus had learnt such a rule (4 out of 5 instances of word-initial /ka(ː)/ are spelt with <k>). Interestingly, although there is a small number of personal names being spelt with <k>, it is not clear that it is their status as personal names that triggers the <k>: in the two instances of Karus at Vindolanda, the cognomen is also a lexeme which anyway tends to be spelt with <k>, and in the examples in the Isola Sacra inscriptions there are no other instances of /ka(ː)/. Outside the lexeme carus, use of <k> may have a remarkable twofold correlation: on the one hand with substandard spelling, and on the other hand with other old-fashioned spellings.

<q> before /u(ː)/

Reference Wallace and ClacksonWallace (2011: 27 fn. 29) notes that <q> before /u(ː)/ ‘is found with some frequency in late Republican Latin, particularly in the word for “money”’ [i.e. pecūnia], and that it is ‘also found sporadically in Imperial Latin texts’. On the whole, a more comprehensive investigation supports Wallace’s statements. Searches on the EDCS show that pequnia is found in 39 dated inscriptions up to the end of the first century BC, pecunia in 45, giving a frequency of 46%,Footnote 24 which is higher than most other lexical items containing this sequence:Footnote 25 Merqurius, Mirqurius is found in 4 inscriptions, Mercurius, Mircurius, Mercurialis in 18, giving a frequency of 18%; sequndum, Sequndus is found in 4 inscriptions, secundus, secundum, Secundius in 52, giving a frequency of 7%; cura and forms of curare are found in 71 inscriptions, where qura only appears once (1%), although the low number of instances of <q> is probably due to the existence of the alternative spelling coera-.

The numbers of inscriptions with <q> decline significantly in the period of the first to fourth centuries AD, but the relative preponderance of pequnia continues:Footnote 26 it is found in 20 inscriptions dated from the first to the fourth centuries AD, while pecunia is in 650, to give a frequency of 3%. A search for curauit, curauerunt between the first and fourth centuries AD gave 750 inscriptions, while there were 6 with quravit, quraverunt, a frequency of 0.8%. Only 2 examples of sequritas are found (both from fourth century AD inscriptions), while securus, securitas, Securius are found in 243 inscriptions, also a frequency of 0.8%. 2 inscriptions contain Merqurius, and 773 have Mercurius, a frequency of 0.3%.Footnote 27 There were 3 inscriptions containing Sequndus, Sequndinus (all names), and 3241 containing secundus (including as a name), Secundius, Secundulus, Secundinus, secundum, giving a rate of 0.09%. Not all words containing /ku/ have variants with <qu>. For example, there were 61 instances of secum between the first and fourth centuries, and none of sequm.

This data suggests that pecūnia is one of the most frequent words which appears spelt with <q>.Footnote 28 This is true both in the earlier period up to the end of the first century BC and in the period of the first to fourth century AD, even though the rate at which <q> was used for /k/ declined significantly in the first to fourth centuries AD compared to the earlier period.Footnote 29 In both periods, the rate at which <q> was used varies between lexemes.

The decline in the use of <q> before /u(ː)/ that we see in inscriptions is reflected in the relative lack of attention to this spelling provided by the writers on language (see pp. 138–43 for the relevant passages). Although it is often noted that <q> is only used before <u>, the examples given generally make it clear that the writer is thinking of the use of <qu> for /kw/, rather than /ku(ː)/ (e.g. Maximus Victorinus, Ars grammatica, GL 6.195.19-23–196.1; the same may be true of Donatus, Ars grammatica maior 1.2, p. 604.16–605.2). Already in the mid-first century AD, Cornutus’ rule (at Cassiodorus, De orthographia 1.23–24) makes it clear that <q> is only to be used when it is followed by <u> and one or more vowels, i.e. when it represents /kw/, and this is implied also by another passage (De orthographia 1.45–48); the same rule is stated by Curtius Valerianus (in Cassiodorus, De orthographia 3.1). Velius Longus (De orthographia 13.10), Marius Victorinus (Ars grammatica 4.36), and perhaps Terentianus Maurus (De litteris 204–209) are aware of <q> before /u/, and all deprecate it,Footnote 30 suggesting that it may have had some continued currency, but was presumably a minority usage. Servius (Commentarius in Artem Donati, GL 4 422.35–423.4) describes it as an old custom, no longer in use.

The use of <q> for /k/ before /u/ is found occasionally in the corpora, but is neither frequent nor widespread. There are no examples in the TPSulp. (dozens of cases, including 18 of pecunia) or TH2 tablets (31 instances, including 4 of pecunia), nor in the graffiti from the Paedagogium (20 instances of <cu>), the Bu Njem ostraca (35 instances of <cu>), the tablets from Vindonissa (14 instances of <cu>), or the Isola Sacra inscriptions (71 instances of <cu>). Among dozens of instances of <cu> from Dura Europos, the only exception is in the name Iaqubus (P. Dura 100.xxvii.12, 101.i.f.3, 101.xxix.14, Dura 101.xxxv.15), where it presumably reflects an attempt to represent non-Latin phonology.

In the Jucundus tablets, the scribe of the earliest tablet twice writes pequnia (CIL 4.3340.1, AD 15); this text does not contain any other cases of /ku/. All subsequent scribes use <cu> in this lexeme (38 instances); in total there are more than 200 instances of <cu> used by both scribes and other writers. There is only one other certain instance of <qu>: Iuqundo (45, undated but presumably in the 50s or 60s AD); there are no other cases of /ku/ in this part of the text, which was written by P. Alfenus Varus, the first centurion of the praetorian cohorts, and subsequently praetorian prefect under Vitellius. His spelling is substandard (problems with geminates: Augussti for Augusti, acepisse for accepisse, Pollionnis for Pollionis, acctum for actum; missing final /m/: noue for nouem; misplaced aspirate: Nucherina for Nucerina).Footnote 31 Both Privatus, the slave of the colony of Pompeii, and the scribe on his tablets use <q> several times in pasqua for pascua ‘pastureland’ (145, 146, 147), beside 1 instance of pascua[m] (146). However, this spelling could reflect the reduction of /ku/ to /kw/ before a vowel, and this seems particularly likely since there are another 15 instances of <cu> in tablets 145–147, used by both Privatus and the scribe.

There are two doubtful examples in the Vindolanda tablets beside more than a hundred instances of <cu>: q̣uụr (Tab. Vindol. 652) for cūr ‘why’ could be analysed as having <q> for /k/ and <uu> for /uː/, but since the use of double letters for long vowels is not otherwise found at Vindolanda, and seems to be very uncommon by the end of the first century AD (see pp. 129–31), it is more likely that this is an etymological spelling with <qu> for /k/ < *kw before a back vowel (see pp. 165–8). In quequmque (Tab. Vindol. 643) for quaecumque ‘whatever’ it seems not improbable that <q> before <u> is triggered by the <qu> in the preceding and following syllables (<c> is used elsewhere in this letter in arculam, securem).

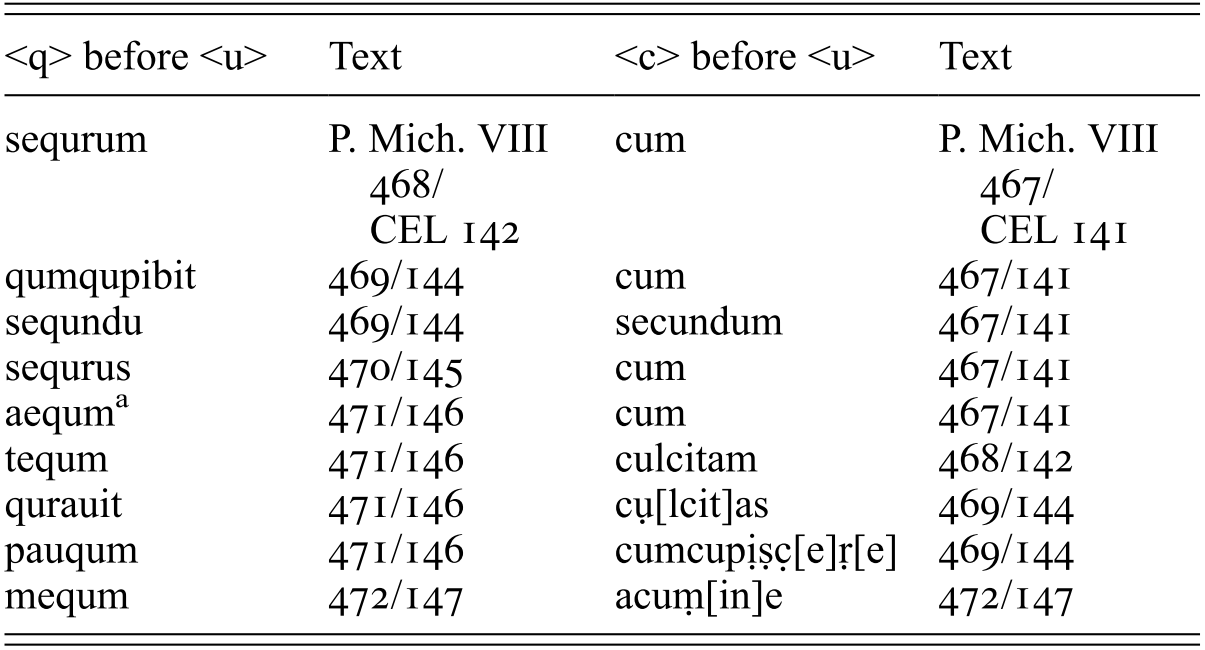

Compared to the absence of <qu> for /ku/ at Vindolanda, it is striking that it was clearly part of the orthography of several of the (presumably) military scribes writing the Claudius Tiberianus letters (Table 17), although it appears to be used consistently only in P. Mich. VIII 471/CEL 146 (and perhaps 470/145); all of these letters except 472/147 show substandard spelling.

Table 17 <q> and <c> before <u> in the Claudius Tiberianus letters

| <q> before <u> | Text | <c> before <u> | Text |

|---|---|---|---|

| sequrum | P. Mich. VIII 468/CEL 142 | cum | P. Mich. VIII 467/CEL 141 |

| qumqupibit | 469/144 | cum | 467/141 |

| sequndu | 469/144 | secundum | 467/141 |

| sequrus | 470/145 | cum | 467/141 |

| aequmFootnote a | 471/146 | cum | 467/141 |

| tequm | 471/146 | culcitam | 468/142 |

| qurauit | 471/146 | cụ[lcit]as | 469/144 |

| pauqum | 471/146 | cumcupịṣc̣[e]ṛ[e] | 469/144 |

| mequm | 472/147 | acuṃ[in]e | 472/147 |

a Presumably aequm for aequum represents spoken [ae̯kum], with reduction of /kw/ to [k] before a back vowel; although here the standard spelling may have influenced the use of <q>.

In the other texts from CEL, there are two instances of <q> before <u>: ]q̣ụṣ, presumably for -cus (CEL 7),Footnote 32 dated to a little before 25 BC, and qum for cum (CEL 10, the letter of Suneros, Augustan period); both also contain 2 instances of <cu>. CEL 7 contains some substandard features (nuc for nunc ‘now’, c̣ic̣quam for quicquam), as well as <u> for <i> in optumos for optimōs ‘best’ (although this is probably not old-fashioned at this time), while CEL 10 has spelling which is conservative to old-fashioned, as well as substandard features (see pp. 10–11). Otherwise only <cu> is found, in large numbers, in CEL.

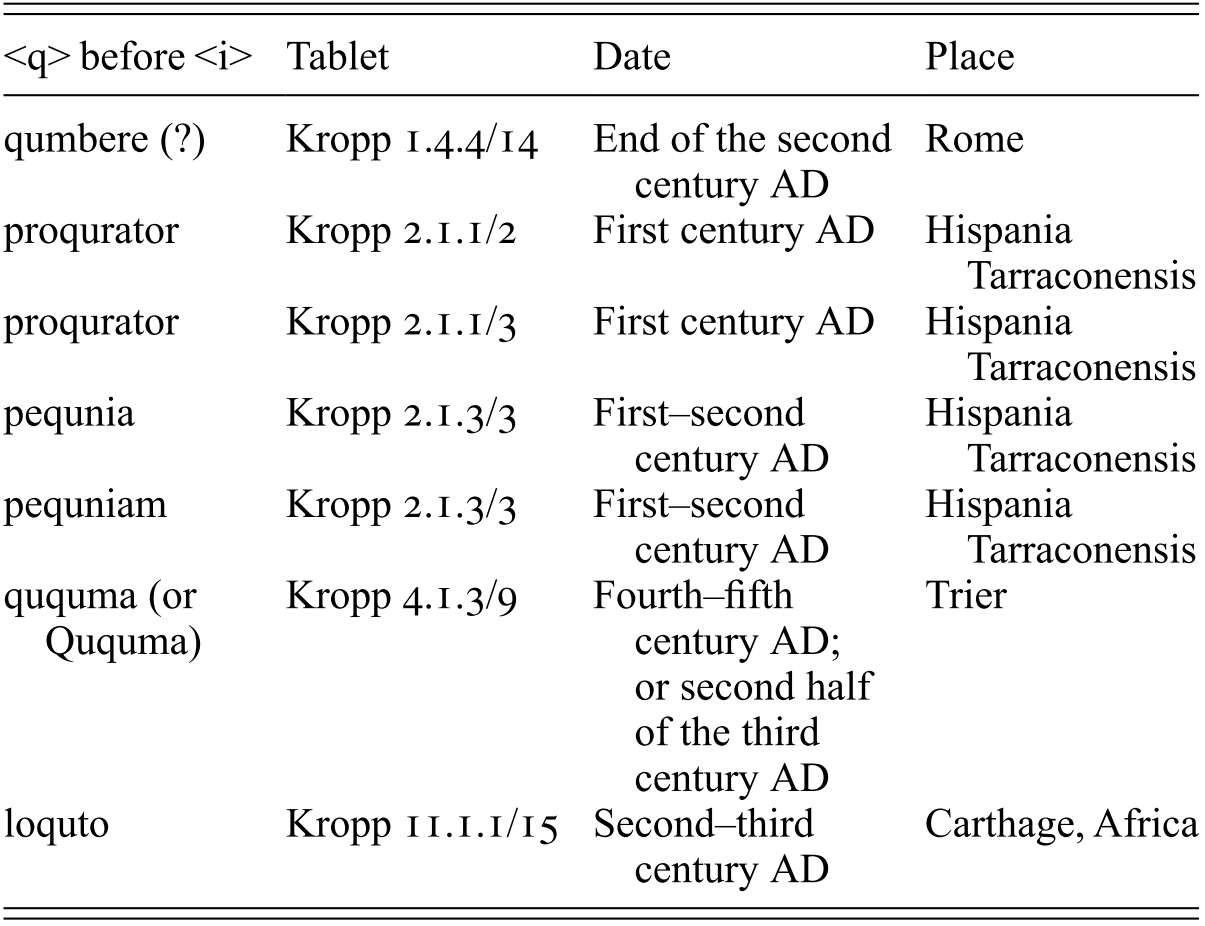

The curse tablets also occasionally use <q>, across the first to third (or fourth or fifth) centuries AD (Table 18). Again, the middle <q> in quiqumque (Kropp 11.2.1/3) may have been instigated by the <q> in the preceding and following syllables. In Kropp 2.1.3/3, pequnia and pequniam for pecūnia with <q> are found beside qicumqui for quīcumque. The spelling is substandard: Cr[y]se for Chrysē, uius for huius, onori for honōri, senus for sinus, o[c]elus for ocellus; substandard spelling occurs also in Kropp 4.1.3/9 (uinculares for uinculāris) and in Kropp 11.1.1/15 (demo[n– for daemōn, oc for hōc, [a]c for hāc, ora for hōra). This small number of instances of <q> compares with more than 200 of <c> before <u> across the corpus

Table 18 <q> before <u> in the curse tablets

| <q> before <i> | Tablet | Date | Place |

|---|---|---|---|

| qumbere (?) | Kropp 1.4.4/14 | End of the second century AD | Rome |

| proqurator | Kropp 2.1.1/2 | First century AD | Hispania Tarraconensis |

| proqurator | Kropp 2.1.1/3 | First century AD | Hispania Tarraconensis |

| pequnia | Kropp 2.1.3/3 | First–second century AD | Hispania Tarraconensis |

| pequniam | Kropp 2.1.3/3 | First–second century AD | Hispania Tarraconensis |

| ququma (or Ququma) | Kropp 4.1.3/9 | Fourth–fifth century AD; or second half of the third century AD | Trier |

| loquto | Kropp 11.1.1/15 | Second–third century AD | Carthage, Africa |

On the whole, those corpora which are more homogeneous, and produced in an environment which might favour uniformity of orthography, avoid <q> for /k/, in particular the scribes of the various Pompeian tablets, and texts from the army bases at Vindolanda, Vindonissa, Bu Njem, and Dura Europos as well as the Paedagogium. The single instance in the earliest Caecilius Jucundus tablet, and the Augustan dating of CEL 7 and 10, hint at a move away from its use in the first century AD (which we would expect on the basis of the inscriptional evidence). However, its use by P. Alfenus Varus in the Jucundus tablets, its appearance in a small number of the curse tablets, and in particular the quite remarkable cluster of instances in the Claudius Tiberianus letters, suggest that use of <q> maintained a somewhat underground existence in certain educational traditions. Given the assumption that the Claudius Tiberianus letters were written by military scribes, the use of <q> in some of them is particularly surprising. But, as already noted, these texts are remarkably heterogeneous in other features of their spelling, which might support the idea that their scribes had been educated in a less consistent fashion than in the other army corpora; I am not sure whether this means we should rethink the assumption that this education took place in the army.

There is not really enough evidence to discuss the lexical distribution of <q>; out of 20 tokens including <q>, 3 are pequnia, which may reflect the preponderance of this lexeme in the inscriptional evidence identified at the start of this section. However, we do not know how the scribe of CIL 4.3340.1 would have written other examples of /ku/ so cannot be sure that pecūnia had any special orthographic status for him; in Kropp 2.1.3/3 qicumqui does compare with pequnia.