The writers on language were aware that <c> had previously been used for /g/ (e.g. Terentianus Maurus 210–211, 894–901 = GL 6.331.210–211, .351.894–.352.891). Instances of <c> for <g> are occasionally found in my corpora, but it is hard to take them seriously as examples of old-fashioned spelling.Footnote 1 In the curse tablets there are scores, if not hundreds, of instances of <g> in the corpus as a whole, and in most cases the few apparent cases of <c> are probably to be put down to the difficulty of distinguishing <c> from <g>, either in the writing or reading of small letters on a thin piece of soft metal which is generally then subject to folding and unfolding, abrasion, water and other types of damage etc. – cf. Reference VäänänenVäänänen’s (1966: 53) comment that instances of <c> for <g> at Pompeii are ‘simple writing errors’ (‘simples erreurs d’écriture’). For similar reasons, the few instances of <c> for <g> in the graffiti from the Palatine are not to be taken seriously.

Most of the curse tablets have only one or two apparent examples of <c> for <g>. Kropp 1.4.3/2 has colico for colligō beside two other cases of <g>, 1.10.2/1 has [r]oco for rogō beside rogo twice. 3.2/25 has no other instances of <g> beside sacellum for sagellum, but is fairly short. 3.14/1 has defico for defigō and also a number of mechanical errors: intermxixi/ta for intermixta, fata for facta (if this is not due to assimilation), sci for sīc, possitt for possit, amere for amārae. 11.1.1/3, along with two examples of Callicraphae for Calligraphae, has seven other examples of <g>.

In the first to fourth century AD, only 1.4.1/1 (Minturnae, c. AD 50) gives the impression that <c> for <g> could be intentional:Footnote 2 it is used for all instances of /g/, in acat for agat, ficura for figūram, dicitos and ticidos for digitōs, and cenua for genua. However, it also has hbetes for habētis, tadro for tradō, uitu for uultum, fulmones for pulmōnes, dabescete for tabēscentem, and ticidos for digitōs. In particular, the use of <f> for <p>, <d> for <t>, and <t> for <d> suggests that the writer, as well as being prone to errors such as omitting or transposing letters, had particular problems in identifying stops correctly. Something weird is going on, but use of <c> for <g> cannot be attributed certainly to the type of education the writer received, rather than linguistic problems (or, conceivably, a form of ‘magical’ writing).

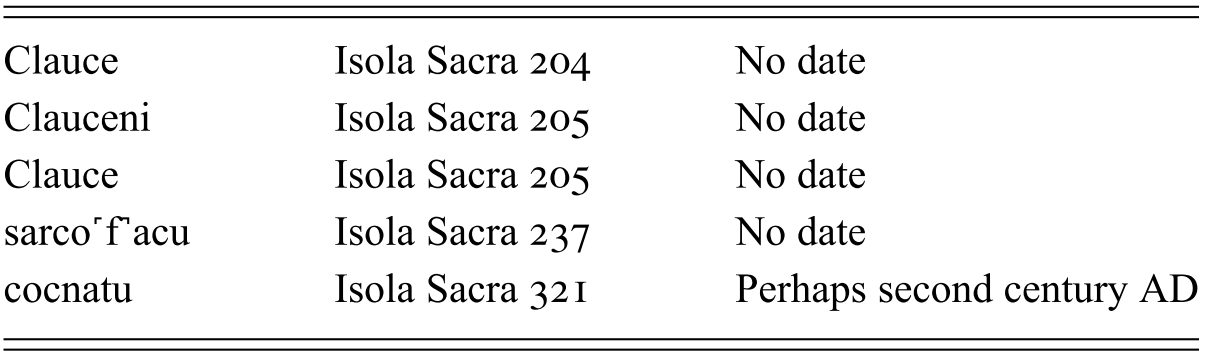

Visible in a small number of the Isola Sacra inscriptions is a curious tendency for /g/ to be represented by <c> when there is another <c> in the word (see Table 13). Whatever the explanation for this, it seems unlikely that it has anything to do with old-fashioned spelling.

Table 13 <c> for <g> in the Isola Sacra inscriptions

| Clauce | Isola Sacra 204 | No date |

| Clauceni | Isola Sacra 205 | No date |

| Clauce | Isola Sacra 205 | No date |

| sarco˹f˺acu | Isola Sacra 237 | No date |

| cocnatu | Isola Sacra 321 | Perhaps second century AD |

Apart from in these corpora, the only other example of <c> for <g> is q]uadrincẹnto (CEL 157, AD 167, Egypt) for quadringenti, where the editor is probably correct to suspect influence from centum ‘one hundred’ (the letter contains another 5 examples of <g>).