The apex was a diacritical sign which appears in inscriptional evidence above or to the right of the vowel sign it modifies.Footnote 1 The earliest datable example, according to Reference OliverOliver (1966: 50), is múrum (CIL 12.679, 104 BC). We are informed by the writers on language that the purpose of the apex was to mark vowel length. Thus Quintilian notes, of the letters for vowels:

at, quae ut uocales iunguntur, aut unam longam faciunt, ut ueteres scripserunt, qui geminatione earum uelut apice utebantur aut duas …

When joined together as vowels, however, they either make one long vowel (as in the old writers who used double vowels instead of an apex) or two vowels …Footnote 2

ut longis syllabis omnibus adponere apicem ineptissimum est, quia plurimae natura ipsa uerbi, quod scribitur, patent, sed interim necessarium, cum eadem littera alium atque alium intellectum, prout correpta uel producta est, facit: ut “malus” arborem significat an hominem non bonum, apice distinguitur, “palus” aliud priore syllaba longa, aliud sequenti significat, et cum eadem littera nominatiuo casu breuis, ablatiuo longa est, utrum sequamur, plerumque hac nota monendi sumus.

For example: it would be very silly to put an apex over all long syllables, because the length of most of them is obvious from the nature of the word which is written, but it is sometimes necessary, namely when the same letter produces different senses if it is long and if it is short. Thus, in malus, an apex indicates that it means “apple tree” and not “bad man”; palus also means one thing if the first syllable is long and another if the second is long; and when the same letter is found as short in the nominative and as long in the ablative, we commonly need to be reminded which interpretation to choose.Footnote 3

A fragment following the De orthographia of Terentius Scaurus in the manuscripts and sometimes attributed to him (see Reference ZetzelZetzel 2018: 319) also provides some information about the apex:

apices ibi poni debent, ubi isdem litteris alia atque alia res designatur, ut uénit et uenit, áret et aret, légit et legit, ceteraque his similia. super i tamen litteram apex non ponitur: melius enim [i pila] in longum producetur. ceterae uocales, quae eodem ordine positae diuersa significant, apice distinguuntur, ne legens dubitatione impediatur, hoc est ne uno sono eaedem pronuntientur.

Apices ought to be placed where by means of the same spelling two different words are written, such as uēnit and uenit, āret and aret, lēgit and legit, and other similar instances. No apex is placed over the letter i: it is better for this to be pronounced long by means of i-longa. Other vowels, which, placed in the same order, signify different things, are distinguished by an apex, so that the reader is not impeded by uncertainty, that is so that he does not pronounce with the same sound these same vowels.

From these two writers then, it is generally gathered that apices and i-longa were used to mark long vowels,Footnote 4 but they recommend using them only when words are distinguished only by length of a vowel. This part of the prescription of Quintilian and ‘Scaurus’, that apices should be used only to distinguish words that were otherwise written identically, is not followed in any inscription of any length (Reference RolfeRolfe 1922: 88, 92; Reference OliverOliver 1966: 133–8).

A couple of letters may suggest that some writers aimed to use apices not only on long vowels, but also on most, if not all, long vowels (except for /iː/, which seldom receives an apex). One of these is CEL 8, written on papyrus, which is dated to between 24 and 21 BC, and probably comes from a military scriptorium. Reference KramerKramer (1991) provides a different reading from that of CEL. If he is correct, this would be an example of (almost) every long vowel being marked:Footnote 5 44 apices or i-longa on 49 long vowels, plus 1 i-longa on a short vowel; but of the 5 missing a mark, 2 are in areas where the papyrus is damaged, so they might have been lost.Footnote 6 CEL 83 is a papyrus letter from the Fayûm, described by the editor as ‘in elegant epistular cursive’ (in corsiva epistolare elegante), and again perhaps in a military context. Cugusi prefers a date in the second half of the first century AD, but second and third century dates have been suggested. This letter contains 14 apices, 7 on /ɔː/, 4 on /aː/, 1 on /eː/, 1 on /uː/ and 1 on /iː/ (there are no instances of i-longa). This compares to 3 other instances of /ɔː/ without an apex and 2 of /uː/ (and 9 of /iː/).

Apart from these rare cases, exactly what rule or rules governed the placement of apices therefore often remains obscure, and may vary according to time, place, register or genre, or training. There are three variables which are relevant for our discussion of apices, and to some extent also i-longa. These are (1) the position in the text or nature of a word which contains an apex or i-longa, (2) the position in the word of a vowel or diphthong which bears an apex or which is an i-longa, and (3) the nature of the vowel (or diphthong) that bears an apex: (a) is it long or short (if it is a single vowel), and (b) what vowel or diphthong is it? In the case of i-longa, the relevant question for (3) is whether it represents long or short /i(ː)/ or consonantal /j/. These variables are not necessarily independent: for instance, if the writer was marking all long vowels in a text with an apex or i-longa, or were following the advice of Quintilian and ‘Scaurus’ to only mark long vowels in homonyms, this would obviously determine their position in both the text and in the word. However, when the situation is not so clear-cut, as it nearly never is, it is important to take these variables into account, and to consider which apply. As we shall see, there is considerable variation in our texts, or at least those for which the editions provide information about apices and i-longa. This variation is extremely interesting in terms of the questions surrounding sub-elite education that I am addressing in this book, since it suggests that individual groups of scribes or stonemasons had developed their own rules for when and where to use these diacritics.

Apices and i-longa have been the subject of a number of studies, which have discussed some of the variables which we have mentioned. The use of the apex primarily to mark long vowels (but not all long vowels) is largely confirmed by long inscriptions which presumably reflect elite usage such as the evidence of the Laudatio Turiae of 15–9 BC (CIL 6.1527, 6.37053; EDR093344), and the Res Gestae Diui Augusti of AD 14 (Reference ScheidScheid 2007; CIL 3, pp. 769–99), as discussed by Reference Flobert and CalboliFlobert (1990: 103–4). The first of these has 5 apices on short vowels or diphthongs out of 134 apices altogether (so 129/134 = 96% long vowels), while the Res Gestae has 9 out of 427 (418/427 = 98% long vowels). However, this is by no means consistent across all inscriptions. Reference Flobert and CalboliFlobert’s (1990) corpus of inscriptions from Vienne and Lyon has 75–77% of apices on long vowels, and Reference ChristiansenChristiansen (1889: 17) notes the relative frequency of an apex on <ae>.Footnote 7

The passage of ‘Scaurus’ also implies that i-longa is the equivalent of the apex, that is it is used to mark vowel length for /iː/. While, again, this is true in some inscriptions, Reference ChristiansenChristiansen (1889: 29–32) identified many cases where it represented /j/, and also suggested that it was used for purely ornamental purposes, at the start of an inscription, at the beginning or end of a line, or even to mark a new phrase (Reference ChristiansenChristiansen 1889: 36–7). Many of the examples of ornamental or text-organisational i-longa are found on a short /i/. Very similar conclusions were drawn from an examination of the inscriptions from Hispania by Reference Rodríguez AdradosRodríguez Adrados (1971), and from a corpus of military diplomas dating from AD 52 to 300 by Reference García González and AnonymousGarcía González (1994). This latter provides some further evidence for the use of i-longa as ornamental, or as a way of marking out text structure, in observing that use of i-longa in the abbreviation imp(erator) correlates with position at the start of the diploma, and is not used so frequently in other places in the text (Reference García González and AnonymousGarcía González 1994: 523).

Reference RolfeRolfe (1922) identified several tendencies in placement of the apex (and i-longa) in the inscriptional texts he examined. Firstly, that they tend to be used frequently in some passages but not in others; two words in agreement often both bear them, but sometimes consecutive non-agreeing words also have them. Secondly, that they seem to add dignity or majesty to certain terms, especially connected with the Emperor and official titles; frequent use in names may also fall under this heading. Thirdly, they act as a type of punctuation, before a section mark in the Res Gestae or where punctuation is used in the English translation. Fourthly, they appear on the preposition a, and on monosyllabic words in general. Lastly, they mark preverbs, word division in compounds and close phrases, suffixes, case endings, and verbs in the perfect tense. In his study of apices and i-longa, Reference Flobert and CalboliFlobert (1990: 106), assuming that their basic purpose is to mark long vowels, suggests reasons for cases on short vowels. Like Rolfe, he sees them as a marker of an important word or name, and draws attention to the use of i-longa in his corpus in the name of the Emperor Tiberius (although for some doubt about this, see pp. 256–7).Footnote 8 More recently, Reference FortsonFortson (2020) has identified, in an inscription of the Arval Brothers (CIL 6.2080, AD 120), the use of apices and i-longa to mark out phrase units, generally on the last word of the phrase.Footnote 9

Most of the evidence for apices and i-longa mentioned above has come from inscriptions on stone or bronze, often with a particular focus on the long official/elite inscriptions such as the Res Gestae and the speech of Claudius from Lyon (CIL 13.1668).Footnote 10 In the following sections I will discuss the evidence of some sub-elite corpora, on stone in the case of the funerary inscriptions of the Isola Sacra, and on wax or wooden tablets in the case of the archive of the Sulpicii, and the texts from Herculaneum and Vindolanda.Footnote 11 These will suggest that use of apices and i-longa in these corpora was often rather different from the picture shown by our elite sources, and that it was often associated in particular with scribes and stonemasons rather than other writers, thus providing evidence for their orthographic education.

Since the relatively few letters which boast apices do not form a cohesive corpus in terms of time or place of composition, I will not discuss them at great length here.Footnote 12 A couple of relevant instances have already been mentioned above. In general, the letters match expectations on the basis of the evidence of the writers on language and the elite inscriptions in that the apices appear almost entirely on long vowels: out of a total of 73 apices (using the reading of Reference KramerKramer 1991 for CEL 8), all but 2 or 3 are non-long vowels: the exceptions are Cláudi (CEL 72), epistolám (CEL 166), where the vowel is phonetically long [ãː], and perhaps ].gó (CEL 85), which, if it is ego, marks a historically long vowel. This makes the divergent usage in the other corpora all the more striking (especially at Vindolanda, where many of the texts containing apices are letters).

Since, as already mentioned, and as will become even clearer from the discussion below, i-longa and apices generally cannot be considered as simply equivalents of each other for /i/ and other vowels respectively, I will discuss the two features separately. The exception to this is the discussion of the Isola Sacra inscriptions with which I begin, where it makes sense to take the two together because their use is rather similar.

Before we turn to these particular corpora in detail, however, it is worth pointing out two serious methodological problems in dealing with apices and i-longa. One of these is the question of how to recognise long and short vowels. Latin underwent a number of sound changes which affected inherited long and short vowels, such that it is not always easy to be sure whether a given vowel was long or short at the time and place of writing of a given document, nor whether length was phonological or phonetic. Of particular relevance are iambic shortening and shortening of other long word-final syllables, and lengthening before /r/ in a syllable coda (see pp. 42–3). I will assume here that in originally iambic words which were paradigmatically isolated, like ego < egō ‘I’, the final vowel is short, but that all other originally long final vowels, even in iambic word forms which are not paradigmatically isolated, were long (or at least, it was known that these ‘should’ be long). I will also assume that vowels before coda /r/ could be phonetically long.

The second issue is the question of what is being counted. If we want to draw conclusions about the use of apices or i-longa it is important to know which vowels are marked in this fashion, but also which are not. For example, as we shall see, Adams observes that apices are particularly common on word-final /a(ː)/ and /ɔ(ː)/ in the Vindolanda tablets. However, this information is incomplete unless we also know what proportion these instances of apices make up of relevant vowels in these tablets. To take an example: suppose in the tablets containing <á> and <ó> these were the only vowels (or the only long vowels, or the only word-final vowels): this would make a significant difference to our analysis of how the apex was being used compared to a situation where there are plentiful examples of /a(ː)/ and /ɔ(ː)/ (not to mention /ɛ(ː)/, /eː/ and /u(ː)/) without apices.

This example was intentionally absurd. But, as we shall see, the tablets do contain a particularly high number of apices on long final /ɔ(ː)/ compared to other text types. This does not necessarily mean that writers at Vindolanda were more fond of putting an apex on /ɔ(ː)/ in this position than on /a(ː)/, but may simply reflect a preponderance of this context: most of the tablets containing apices are letters written to and from men; consequently the greetings formula and addresses of these letters tend to contain large numbers of second declension nouns in the dative and ablative; likewise, names mentioned in the main text are more commonly men than women.

To collect all instances of vowels without apices as well as with apices in the Vindolanda tablets, or in other large corpora which have apices and i-longa, would be overwhelming, but I will look closely at some texts which have relatively large numbers, in order to get at least a qualitative idea of whether the picture from looking over the whole corpus seems to fit in with the practice in individual texts.

Several of the Isola Sacra funerary inscriptions contain apices (see Table 31). The most important variable in the use of the apices is position in the text. Their main purpose is to emphasise the initial dīs mānibus formula (as noted by Reference ChristiansenChristiansen 1889: 12) and/or some or all of the names on the tomb (particularly the names of the deceased, or the person for whom the tomb is intended).Footnote 1 As will be discussed shortly, although the i-longa is mostly used differently, in some cases it also takes part in this usage. Thus in IS 69, there are apices on mánibus and on three out of four of the non-abbreviated parts of the name formulas of the two dead women, while in IS 70, which uses the abbreviation d. m. for dīs mānibus, there are two name formulas which each receive an apex on the only long vowel (which is not /i:/) in the formula. In some cases words modifying these names are also given apices.

Table 31 Apices in the Isola Sacra inscriptions

| Inscription | dis manibus | Name(s) of deceased | Name(s) of builder | Other words |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IS 69 | dis mánibus | Alfiáe M. f. Prócilláe | P. Sextilius Pannychianus | |

| IS 70 | d. m. |

| ||

| IS 72 | dís mánibús | P. Betileno Synegdemo | Betiliena Antiochis | |

| IS 79 | d.m. | Aphrodisiáe karíssimaé béne merenti | L. Suallius Eupór | |

| IS 97 | diìs m. (right side) | C. Nunnidius Fortunatus | Claudi Luperci | púrumFootnote a |

| IS 110 |

| filí | ||

| IS 128 | diìs mánibus | Iúliae L. f. Apollóniae |

| |

| IS 130 | d. m. | Antoniáe Tyche matrì optimáe | MMM Antoniì Vìtális, Capitó, Ianúárius fíliì | |

| IS 169 | dis manibus |

|

| |

| IS 195 | Ónesimé | Erós cónseru[ | ||

| IS 210 | d. m. |

| Ulpia | |

| IS 253 | d.m. |

| ||

| IS 309 | dìs mánibus | Murdiae Apelidi |

| |

| IS 314 | Ti. Plautị[ | agró | ||

| IS 360 | d.m. | ]li Eutychetis | ]odius Deúther |

a The apex is not printed by the editors, but is noted in the commentary and is clear in the photograph.

In the fairly long IS 253, the initial two name formulas do not receive an apex, but at the second mention of M. Antonius Vitalis an apex is used (on, unusually, an <i>). The two lines containing the name formulas at the start of the inscription are in larger letters than the rest of the text, so it is possible that these were already felt to be appropriately marked out, and not to require an apex.

Apart from IS 127, on which see directly below, out of 15 inscriptions containing apices, only 4 inscriptions (IS 97, 110, 169 and 314) place apices on words that do not fall into these categories. These apices are all on long vowels. The apparent disparities in these texts from the standard practice in the latter two are less stark than they may at first seem. IS 169 is the only inscription which contains the unabbreviated dīs mānibus formula and which does not place an apex on either of the words. However, the first line and most of the second, containing dīs mānibus and the first name formula, have been erased and rewritten. Since both of the other two name formulas in this inscription are given an apex, it is reasonable to suppose that the same would have been true of the first one, and probably also of dīs mānibus. In the case of IS 314 the inscription is extremely damaged and not much text remains, so it is impossible to know whether it would also have used apices on the dīs mānibus formula, or on some of the names as well.

IS 127 shows a markedly divergent, as well as highly enthusiastic, use of apices: the editors identify them as dividing words, indicating abbreviations, filling empty spaces, and indicating the accent. As to the accent position, I presume they refer to the small number of apices which appear above rather than between letters, on the initial letters of every word of the second line Źosimes q́uae úixit, and on tabelĺ(arius). I would analyse the use of apices in the second line as emphasising the name of the deceased (the first line is simply d.m.).

The distribution by vowels and diphthongs is remarkably even, including, unexpectedly, on <i>:

| aː | ɛ | eː | i | iː | ɔ | ɔː | u | uː | ae̯ | ɛu |

| 6 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 2 |

There is a weak tendency for the apex to be placed on long vowels: except for <u>, there are more apices found on the long version of each vowel than on the short; out of the 4 instances of non-abbreviated mānibus which bear the apex, all have an apex on the <a>, and only one (also) has an apex on the <u>; and some inscriptions (IS 70, 128, 309, 169, plus 314 and 253, in which only one apex is found) only use apices on long vowels. Also, all apices which are not on the dīs mānibus formula, on names, or on adjectives agreeing with names, are on a long vowel, although this may be a coincidence. But only 23/38 = 61% apices are on long vowels, with 8 being on diphthongs and 7 on short vowels. As we will see, this is a much lower rate than even the Vindolanda tablets or the tablets of the Sulpicii, both of which show a lower rate than the 75–77% in the Lyon and Vienne inscriptions examined by Reference Flobert and CalboliFlobert (1990). The position in the word is also evenly spread, with only 14/38 (37% plus 1 monosyllable) apices being on the final syllable (again, this is much lower than at Vindolanda or the tablets of the Sulpicii, which favour final syllables).

It seems pretty clear that in general the use of apices in the Isola Sacra inscriptions is for decoration/text structure rather than for the purpose of marking vowel length, although this may have been a secondary consideration, since some inscriptions only used apices on long vowels. IS 169 and perhaps IS 314 took a somewhat different approach, in which only long vowels were marked, even on words which are not part of a name or an attributive noun or adjective phrase – although even in IS 169, 2 out of 4 words with an apex are names.

We must remember that inscriptions from the Isola Sacra which contain apices are very much the minority. Nonetheless, the fact that there is a pattern in the use of apices in the inscriptions which contain them suggests some sort of educational tradition among the writers of these inscriptions, however broadly defined. We might think of a relatively formal tradition among those who were employed to compose funeral inscriptions or advise customers on their composition, a much looser tendency among some writers to reproduce what they find in looking at other funerary inscriptions, or even a habit passed along by the stonemasons of tombstones themselves, adding apices on their own initiative at the time of engraving the texts.

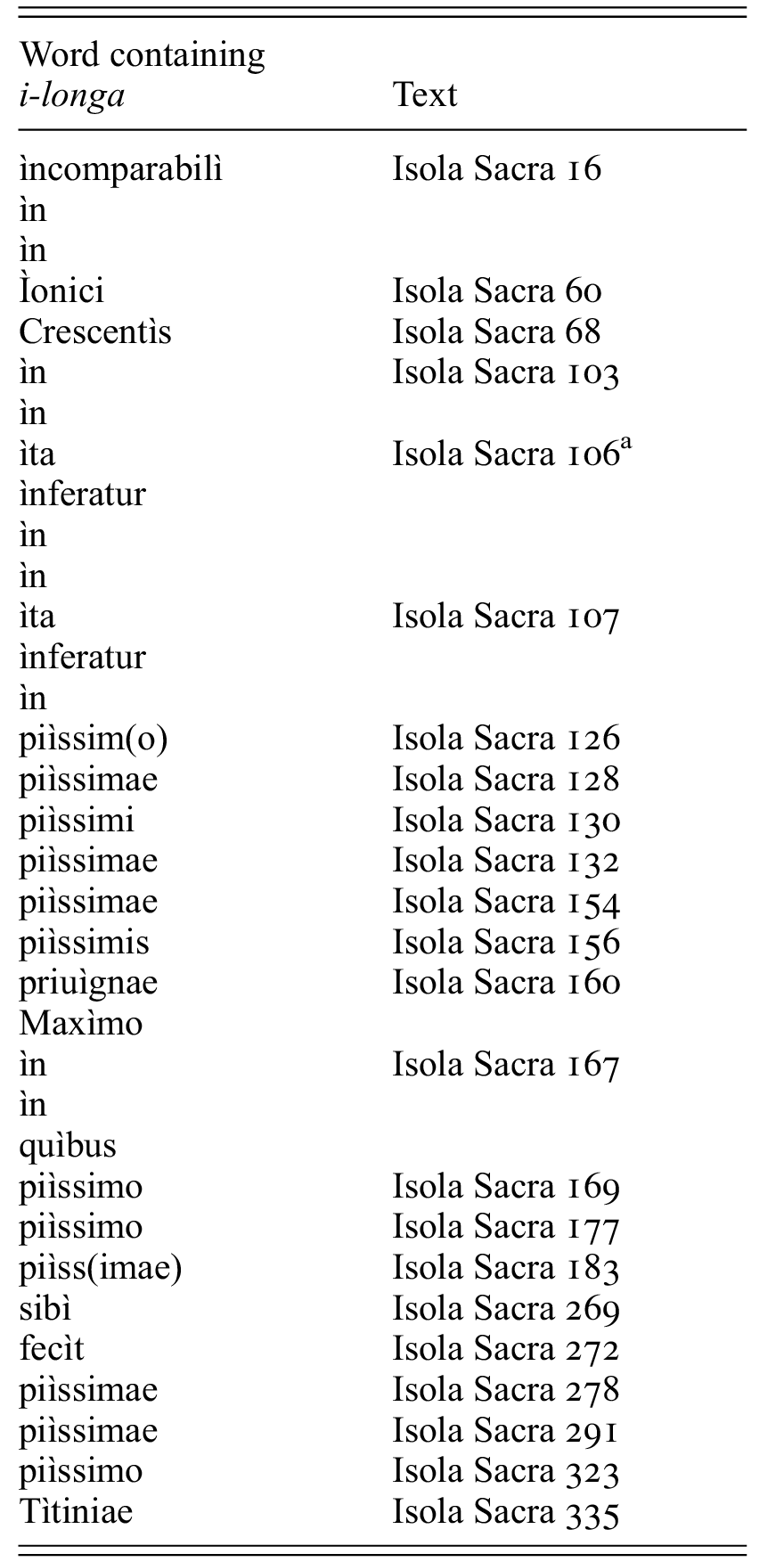

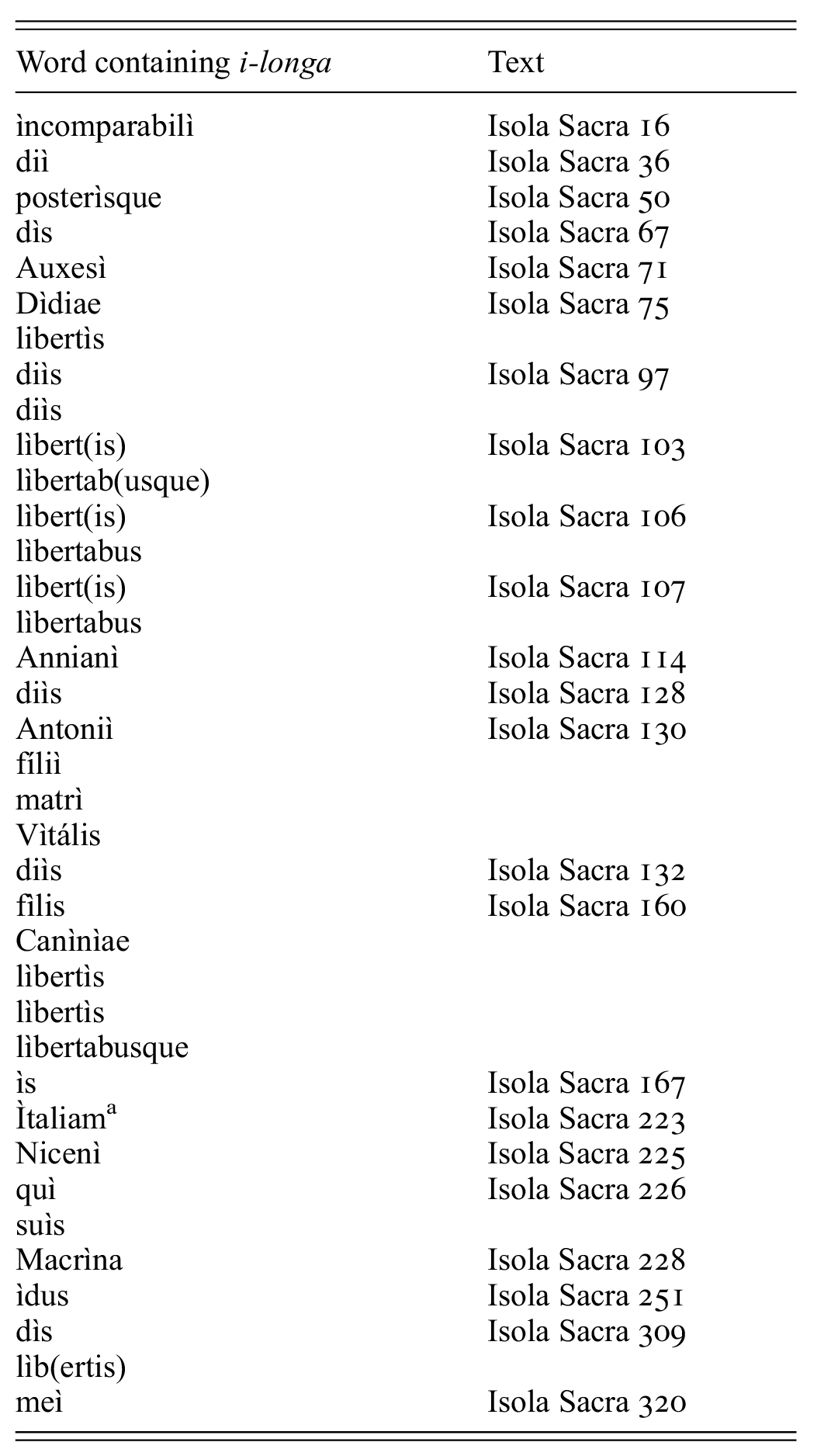

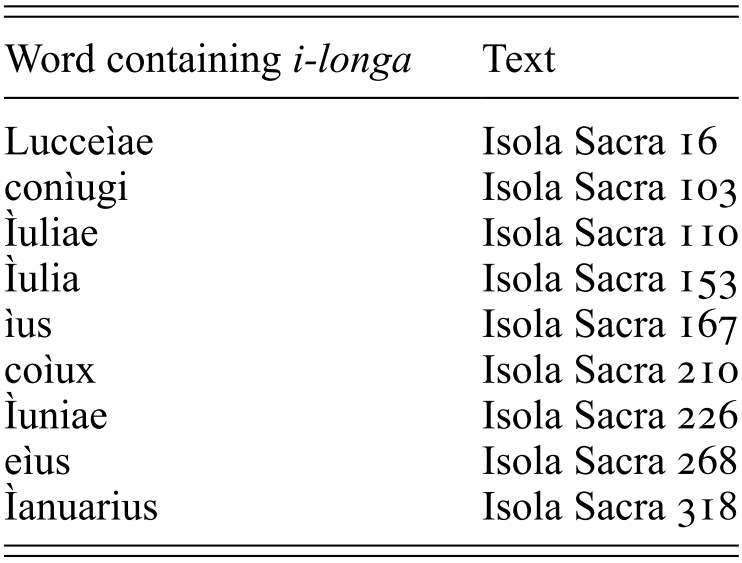

There are 84 instances of i-longa compared to 36 instances of apices in the Isola Sacra inscriptions, introducing the theme we will see in the tablets of the Sulpicii, and those from Herculaneum, of greater use of i-longa than of the apex. As in the other corpora, i-longa is found to represent long /iː/ (37; Table 33), short /i/ (34; Table 32), as well as /j/ (9; Table 34), plus 4 more uncertain whether short /i/ or /j/.Footnote 2 Unlike in the TH2 corpus, where <ì> is massively favoured as a way to write /iː/, a (small) plurality but not a majority of <ì> in the Isola Sacra inscriptions represent /iː/. This matches with the use of apices in this corpus, where marking of long vowels was not a priority.

Table 32 i-longa on short /i/ in the Isola Sacra inscriptions

| Word containing i-longa | Text |

|---|---|

| Isola Sacra 16 |

| Ìonici | Isola Sacra 60 |

| Crescentìs | Isola Sacra 68 |

| Isola Sacra 103 |

| Isola Sacra 106Footnote a |

| Isola Sacra 107 |

| piìssim(o) | Isola Sacra 126 |

| piìssimae | Isola Sacra 128 |

| piìssimi | Isola Sacra 130 |

| piìssimae | Isola Sacra 132 |

| piìssimae | Isola Sacra 154 |

| piìssimis | Isola Sacra 156 |

| Isola Sacra 160 |

| Isola Sacra 167 |

| piìssimo | Isola Sacra 169 |

| piìssimo | Isola Sacra 177 |

| piìss(imae) | Isola Sacra 183 |

| sibì | Isola Sacra 269 |

| fecìt | Isola Sacra 272 |

| piìssimae | Isola Sacra 278 |

| piìssimae | Isola Sacra 291 |

| piìssimo | Isola Sacra 323 |

| Tìtiniae | Isola Sacra 335 |

a The second in in the final line is not marked with an i-longa by the editors, but is clearly visible in the accompanying photo.

Table 33 i-longa on long /iː/ in the Isola Sacra inscriptions

| Word containing i-longa | Text |

|---|---|

| ìncomparabilì | Isola Sacra 16 |

| diì | Isola Sacra 36 |

| posterìsque | Isola Sacra 50 |

| dìs | Isola Sacra 67 |

| Auxesì | Isola Sacra 71 |

| Isola Sacra 75 |

| Isola Sacra 97 |

| Isola Sacra 103 |

| Isola Sacra 106 |

| Isola Sacra 107 |

| Annianì | Isola Sacra 114 |

| diìs | Isola Sacra 128 |

| Isola Sacra 130 |

| diìs | Isola Sacra 132 |

| Isola Sacra 160 |

| ìs | Isola Sacra 167 |

| ÌtaliamFootnote a | Isola Sacra 223 |

| Nicenì | Isola Sacra 225 |

| Isola Sacra 226 |

| Macrìna | Isola Sacra 228 |

| ìdus | Isola Sacra 251 |

| Isola Sacra 309 |

| meì | Isola Sacra 320 |

a In context, as the first syllable of a hexametric line, <i> the is presumably considered long.

Table 34 i-longa on /j/ in the Isola Sacra inscriptions

| Word containing i-longa | Text |

|---|---|

| Lucceìae | Isola Sacra 16 |

| conìugi | Isola Sacra 103 |

| Ìuliae | Isola Sacra 110 |

| Ìulia | Isola Sacra 153 |

| ìus | Isola Sacra 167 |

| coìux | Isola Sacra 210 |

| Ìuniae | Isola Sacra 226 |

| eìus | Isola Sacra 268 |

| Ìanuarius | Isola Sacra 318 |

The reason for this fairly equal distribution is that, even more than with the apices, use of i-longa is often driven by non-strictly linguistic factors, in particular a tendency for i-longa to be used to create visual clarity when preceded or followed by a letter formed with an upright stroke. The clearest example of this is the use of <ì> for the second vowel in a sequence /i.i/ found in the word piissimus, which makes up 12/34 of the instances of i-longa for a short /i/. There was evidently a convention that in such a sequence the second <i> was lengthened for visual clarity.Footnote 3 Many of the examples occur in inscriptions in which i-longa was not otherwise used, despite the presence of other instances of <i> (IS 126, 154, 156, 169,Footnote 4 177, 183, 278, 291, 323), which demonstrates that it is just this sequence which was targeted.

Unsurprisingly, where the second <i> in the sequence represented long /iː/, i-longa is also sometimes found. Again, in IS 36 (diì), 97 (diìs, twice), and 132 (diìs, piìssimae), it is only used in this context. The same is true of 128 (diìs, piìssimae, although long vowels are also given apices in mánibus, Iúliae, Apollóniae). In IS 130, three sequences of <iì> are found (Antoniì, fíliì, piìssimi), but the i-longa is also used to mark long /iː/ in matrì and Vìtális. In these last two inscriptions, an interaction between use of i-longa and the decorational/emphatic purpose of the apex seems possible (diìs agreeing with mánibus, piìssimae with Iúliae and Apollóniae; fíliì and piìssimi agreeing with Vìtális, Capitó, and Ianúárius). In Ìdus (251), the first letter of the word comes directly after the number IIII, so the i-longa here serves a useful function in marking off the number from the start of the word (although there is also an interpunct there is little space between the two).

Practically all the instances of i-longa for short /i/ can be explained by a similar habit, where I is next to N (ìn, ìn-), M (maxìmo) or T (Crescentìs, ìta, Tìtiniae, fecìt), as can many instances for long /iː/ and /j/: L (lìbertis, lìbertabus, fìlis), T (libertìs, Ìtaliam, Vìtális), N (Annianí, Nicenì, Macrìna, Antonì, conìugi). In these cases, the adjacent letters all involve one or two uprights which, when adjacent to the single upright of I, could cause some confusion in reading.Footnote 5 Of course, this may be coincidental, and there are examples of <ì> next to other letters. But support comes firstly from the very clear case of Canìnìae and Can\inìae, where the photo shows how much more difficult to segment the sequence NINI in the former and INI in the latter would be without the use of i-longa; and secondly from the fact that <ì> is not in fact the only letter that takes place in this process. Thus we find, for example, <t> lengthened in Sitti, merenti (IS 68), fecit, Rutiliae (IS 49), fecit (IS 99), optimáe (IS 130), libertis (IS 241, left side), Primitibus (IS 315), fecit, aditum, manumiserit (IS 320), Tattia (IS 332, third <t>) and <l> lengthened in libertis, libertabusque (IS 14), libertis (IS 71), libertab(usque) (IS 120).Footnote 6

Most examples of i-longa can be explained by reference to this practice, as well as the tendency we have already seen in the discussion of apices to use it as one of several methods to emphasise personal names.Footnote 7 In IS 60, for instance, in addition to Ìonici, the <y> found in Alypo and Chrysopolis is considerably higher above the line of the other letters (although there are no examples of <y> in non-names in this inscription to compare it to); the initial <a> of Alypo appears in the photo also to extend higher above the line than elsewhere, although this is not commented on by the editors. The <f> of f(ilio) in the name formula is also described by the editors as ‘grande’ (as well as the <x> of uixit). In IS 71, Auxesì has an elongated <x> as well as the i-longa, as does the <f> of Felici (although, as noted in fn. 6, <f> tends to be elongated before <e> anyway). In IS 75, beside the i-longa of Dìdiae, the second <e> of the cognomen Helpidis bears what the editors call ‘a stroke at the top, lengthened towards the left’ (un trattino superiore … allungato verso sinistra), which seems to be another way of marking out the name. In 130, every word in the sequence Antoniáe Tyche matrì optimáe has either an apex or an elongated letter (in the case of Tyche it is the <y>).Footnote 8

Unlike with the apices, whose use might be a feature of the spelling of the writers of the inscriptions or a practice of the stonemasons themselves, the heavy usage of i-longa as a means of avoiding consecutive upright strokes seems more likely to be due to the stonemasons rather than telling us anything about sub-elite education more widely.

All in all, there are only a handful of cases of i-longa which do not fit into this picture. For example, in 167 the third line features a run of i-longa in ìs quìbus ìus, for which I do not have an explanation, but observe that <ì> is used here on a long /iː/, a short /i/ and a /j/ respectively, so is probably not marking a linguistic feature (there are several other instances of unmarked <i>, as well as two of ìn). There may be one or two instances where the writers are intentionally marking long /iː/ (e.g. quì and suìs in IS 226), but on the whole I would attribute the remaining unexplained cases as due to the practical or aesthetic considerations of the stonemasons. The emphasis on practicality, decoration and text structure over phonology in the use of apices and i-longa in the Isola Sacra inscriptions is something to keep in mind as a parallel when considering usage in the other texts which we are about to look at: although of course in some ways the praxis of writing with ink or a stylus on wood or wax is very different from carving on stone, nonetheless there are – as we shall see – some similarities. They also give us an idea of the range of uses that these features can be put to, which are quite different from those implied by the writers on language and by elite inscriptions.

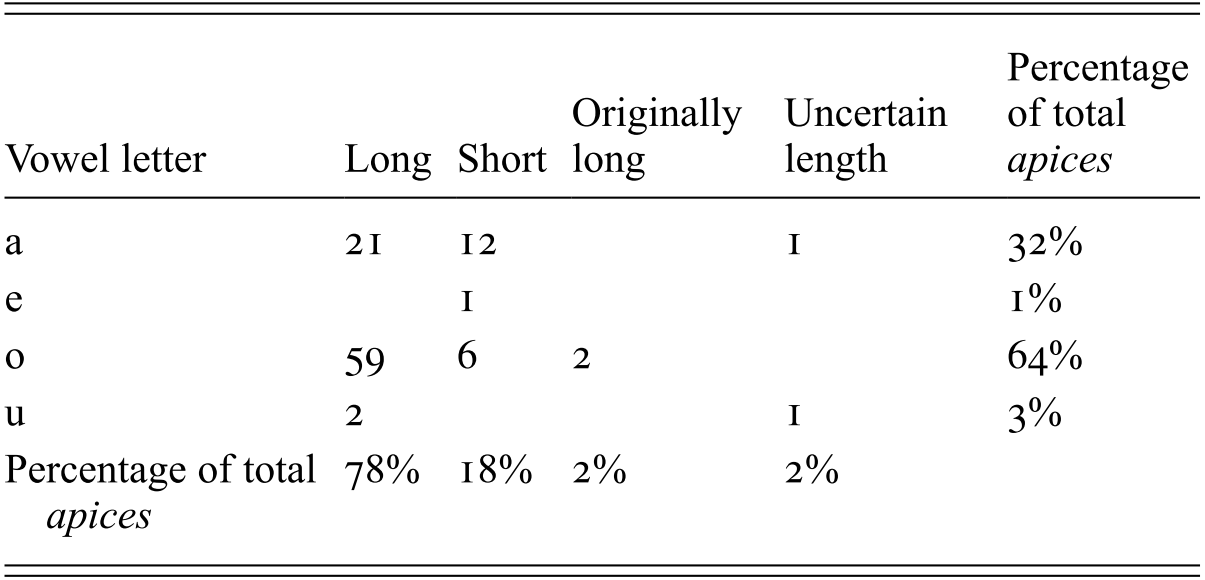

Reference AdamsAdams (1995: 97–8, Reference Adams2003: 531–2) collected most examples of apices in the Vindolanda tablets in Tab. Vindol. II and III. Including some doubtful cases, he counts 92 instances. We can add a further 7 found in the more recently published tablets, and 6 which he omitted.Footnote 1 With the new cases we have a total of 105 instances of apices (Table 35), of which 82 = 78% are on long vowels, and 19 = 18% are on short vowels, with a further 2 = 2% on vowels which were short but used to be long, and 2 = 2% on vowels of uncertain length (Table 36).Footnote 2

Table 35 Apices in the Vindolanda tablets

| Long vowels | Text (Tab. Vindol.) | Short vowels originally long | Text (Tab. Vindol.) | Short vowels | Text (Tab. Vindol.) | Vowels of uncertain length | Text (Tab. Vindol.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 194 |

| 645 |

| 175 | censúsFootnote a | 304 |

| 196 | -neariá | 192 | FrámFootnote b | 734 | ||

| 212 |

| 198 | ||||

| 215 | sagá | 207 | ||||

| Fláuio | 221 | óptamus | 248 | ||||

| Octóbres | 234 |

| 265 | ||||

| 239 |

| 291 | ||||

| numerátioni | 242 | necessariá | 292 | ||||

| 243 | t.[c. 6.]áFootnote c | 588 | ||||

| -róFootnote d | 245 | mágis (possibly) | 611 | ||||

| tú | 248 | dómine | 628 | ||||

| Flauió | 255 |

| 645 | ||||

| suó | 261 | diligénter | 693 | ||||

| tuó | 263 | dómine (possibly) | 796 | ||||

| 265 | ||||||

| 291 | ||||||

| 292 | ||||||

| 305 | ||||||

| exoró | 307 | ||||||

| suó | 310 | ||||||

| 311 | ||||||

| 319 | ||||||

| -innáFootnote f | 324 | ||||||

| ]..s.nióFootnote g | 325 | ||||||

| meó | 330 | ||||||

| Licinió | 580 | ||||||

| stabuló | 581 | ||||||

| á | 588 | ||||||

| [r]ạtió | 608 | ||||||

| 611 | ||||||

| Flauió | 613 | ||||||

| Lepidiná (possibly) | 622 | ||||||

| 628 | ||||||

| suó | 631 | ||||||

| Flauió | 632 | ||||||

| 640 | ||||||

| Ṃarinó | 641 | ||||||

| Flórus | 644 | ||||||

| 645 | ||||||

| Flauió | 648 | ||||||

| fació | 652 | ||||||

| Priscinó | 663 | ||||||

| benefició | 666 | ||||||

| illórum | 693 | ||||||

| immó | 706 | ||||||

| tuá | 880 | ||||||

| 893 | ||||||

| Decmó | 893 add |

a The editors suggest a gen. sg. censūs, but the context is damaged, and nom. sg. census cannot be ruled out.

b On the back of a tablet, probably a name in the address of a letter.

c Perhaps tr[ansla]tá.

d Probably part of a name.

e But the text is not certain here.

f Probably a name in the ablative.

g This is in the address on the back of the letter: it will be a name in the dative.

Table 36 Distribution of apices in the Vindolanda tablets

| Vowel letter | Long | Short | Originally long | Uncertain length | Percentage of total apices |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | 21 | 12 | 1 | 32% | |

| e | 1 | 1% | |||

| o | 59 | 6 | 2 | 64% | |

| u | 2 | 1 | 3% | ||

| Percentage of total apices | 78% | 18% | 2% | 2% |

It seems likely that use of apices was a practice restricted to, or at least most common among, scribes at (and around) Vindolanda. While it is not always easy to tell whether a given tablet at Vindolanda was written by a scribe or by another writer, letters often feature a second hand which provides the final salutation formula, and in these cases it is reasonable to suppose that the first hand is that of a scribe. Sometimes these hands also appear in other texts. The following texts have apices in scribal parts: Tab. Vindol. 234,Footnote 3 239, 242, 243, 245, 248, 263, 291, 292, 305, 310, 311, 611,Footnote 4 613, 622, perhaps 628,Footnote 5 641, 706. Conversely, there are very few or no examples of apices in texts which we know or suspect not to be written by scribes, such as the letters written by Cerialis (225–232), the renuntium reports written by the optiones (127–153), the relatively long closing messages of Lepidina at 291 and 292 (both letters where the scribe uses apices), the letters of Octavius (343) and Florus (643),Footnote 6 and the writer of the letter 344 and accounts 180 and 181.Footnote 7 Of course, it may be that there was a feeling that letters were more formal documents than other types of text, so that use of apices in them may have been more appropriate, as Adams suggests (see fn. 14). However, this does not explain why we don’t find apices in the parts of letters written by non-scribes.

Furthermore, the scribes appear to have been trained in, or to have developed among themselves, a usage of apices that is characteristic of the Vindolanda tablets. Firstly, use of the apex is highly restricted in terms of vowel quality, with /aː/ and /ɔː/ making up practically all the vowels with an apex (101/105 = 96%); secondly, it is highly restricted in terms of position in the word. Not including monosyllables, of which there are 5, 80 (= 80%) instances of the apex are on the final syllable, 76 (= 95%) of these are on an absolute word-final vowel,Footnote 8 and 75 (94%) are on <o> or <a>.Footnote 9 This means that out of all 105 instances of apices, 71% are on absolute word-final <o> or <a>. Now, these are doubtless the most frequent word-final vowels in Latin, probably both in terms of type within the language and token within most texts, but the disproportion in terms of both apex position in the word and letter on which the apex is placed marks the Vindolanda tablets out from other texts containing apices (as we will see in Chapter 21).

Reference AdamsAdams (2003: 531) makes two possible suggestions for the preponderance of final <ó> and <á>:

either that a stylized form of writing is at issue, such that writers, if they remembered, signed off words ending in one or the other of the two long vowels with a sort of flourish, or, if a linguistic explanation is to be sought, that long vowels in final position were subject to shortening in speech, and that scribes were encouraged to use the apex as a mnemonic for preserving the ‘correct’ quantity.

It seems to me less likely that Adams’ linguistic explanation is correct. It is important to note that nearly every word-final /ɔ/ in Latin was long (and all examples of short /ɔ/ came from original /ɔː/, by iambic shortening). This was not the case with /a/ and /aː/. Therefore, if shortening of absolute final vowels had occurred, and the scribes were trying to mark vowels that ought to be long, they would succeed simply by putting an apex on practically every word-final <o>. When it came to <a>, however, such an approach would not work. Indeed, this is what we find: there are only 8 examples of long final /aː/ with an apex, but 9 of short final /a/.

On the face of it, therefore, this is evidence in favour of shortening of word-final vowels: in cases where the scribes actively had to recognise whether an /a/ was long or short, they could not. However, it seems somewhat surprising that the scribes, who were so successful in producing non-intuitive standard spelling in other ways, had not managed successfully to learn this particular feature. Moreover, if the apex was taught as a means of maintaining the correct quantity, it is surprising that we find it so often on final /ɔ/. After all, since there are practically no words which differ in meaning depending on whether final /ɔ/ is long or short, the value in marking it is very little compared to that of final /a/ and /aː/.Footnote 10 Nor is there any point, from this perspective, in the three examples of word-final /aːs/ in which the vowel bears an apex, since there are no verb forms ending in /as/ with which they could have been confused (nor was there a shortening taking place of non–word-final vowels). In addition, when apices are used on non-final syllables, they appear with equal frequency on short vowels as on long vowels (10/20 instances; see Table 37), even though vowel length was still maintained in non-final syllables at this time.Footnote 11 All of this suggests that marking vowel length may not have been the primary purpose of the apex.

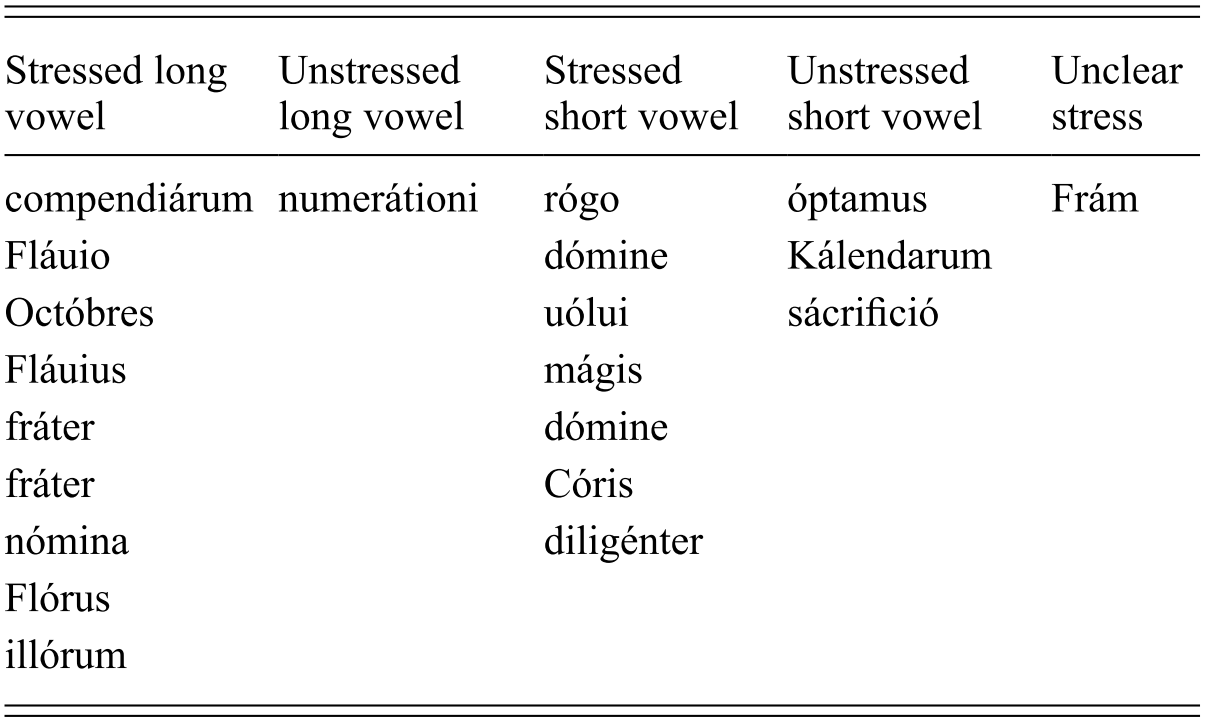

Table 37 Apices on vowels in non-final syllables at Vindolanda

| Stressed long vowel | Unstressed long vowel | Stressed short vowel | Unstressed short vowel | Unclear stress |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| compendiárum | numerátioni | rógo | óptamus | Frám |

| Fláuio | dómine | Kálendarum | ||

| Octóbres | uólui | sácrifició | ||

| Fláuius | mágis | |||

| fráter | dómine | |||

| fráter | Córis | |||

| nómina | diligénter | |||

| Flórus | ||||

| illórum |

Given the divergence of the placement of the apex at Vindolanda from what Quintilian and ‘Scaurus’ say about the apex, and indeed its divergence from other inscriptions and corpora discussed below, it seems reasonable to assume that the scribes were using apices according to their own rules or sense of where an apex was appropriate, which can only be derived from the evidence of the Vindolanda tablets themselves. Although these rules or feelings were not necessarily shared by all scribes, or used consistently by any given scribe, overall we can identify some tendencies. Starting from this position, without preconceived ideas, the most important principle seems to be that the apex should appear on /ɔ(ː)/ or, less often, on /a(ː)/; the next most important that it should appear on a vowel in the final syllable of a word (ideally on a vowel which is word-final).Footnote 12 Given these principles, it is inevitable that most apices will end up on long vowels (or at least vowels which were originally long, if shortening of word-final long vowels has taken place), but this will be epiphenomenal, rather than being a principle in itself.Footnote 13

If the reason for these ranked principles is not linguistic, what is it? It could be connected with the fact that apices seem to be used more in letters than in other types of text.Footnote 14 Using the list showing all tablets from Tab. Vindol. II and III, at Vindolanda Tablets Online II,Footnote 15 I count 129 non-letters, and 206 letters. There are 67 documents containing apices, of which 54 are letters, 12 are not, and 1 is uncertain. The proportion of documents containing apices that are letters is thus much higher than the proportion of letters as a whole at Vindolanda.Footnote 16 There is other evidence that it was a feature of letter writing for apices to have been used on word-final <o> of datives in the greeting formula in the prescript of a letter or the address of a letter on the back, a usage which continues into the third century AD in papyrus letters (Reference KramerKramer 1991: 142; Reference Bowman and ThomasBowman and Thomas 1994: 60–1).Footnote 17 About a third of apices at Vindolanda occur in this context, almost all of them on final <o>. Indeed, there are a certain number of letters where an apex does not appear anywhere except in this context.Footnote 18 A plausible instance of these factors being important is Tab. Vindol. 893, a letter whose author was Caecilius Secundus, the prefect of a unit, probably in the late 80s AD. There are five datives of the second declension with final /oː/, and all five are marked with an apex. Two of these are found in the greetings formula (Vẹrecuṇḍó suó), and two in the address on the back (Iulió Vẹṛecundó), and the remaining instance is a proper name coming directly after the greeting (Decuminó). No other vowels are marked in the text, which includes one other instance of word-final /ɔː/ in scito and several of long final /aː/ (de qua re, in praesentia, as well as the preposition a).

With regard to the position of apices in non-final syllables, Reference Bowman and ThomasBowman and Thomas (1994: 60) have suggested that the presence of the accent may be relevant. As Reference AdamsAdams (1995: 97–8, Reference Adams2003: 531–2) points out, this is not an appealing argument on the basis of Occam’s razor, since this factor cannot explain the far greater number of apices on the final syllable. It is true that there is a certain amount of correlation between apices on non-final syllables and the position of the accent, with 16/20 (= 80%) of instances of apices appearing on vowels in stressed syllables. However, almost the same success rate is found by positing a rule that apices must appear on the initial syllable of a word (16/21 cases = 76%).Footnote 19 Ultimately, the problem is the slightness of the evidence.

I conclude that the very specific tendencies around apex use at Vindolanda probably are not based around their use of diacritics for linguistic purposes, but more as markers of the different part of the text. This would be rather similar to their usage in the Isola Sacra inscriptions. In addition to the tendency for apices to be used in greetings formulas which I have already mentioned, we also find the opposite pattern, where the main text contains apices, which are lacking in the greeting. For example, the brief letter Tab. Vindol. 265 contains a high number of apices, all of which come after the greeting formula C̣ẹṛịạlị suọ salutem. Almost every subsequent instance of /a(ː)/ receives one (fráter, sácrifició, kálendarum, uọluerás), along with word-final /ɔː/ in sácrifició (and not ego). This also has the effect of marking the different parts of the letter. The same pattern is found in 248.

This is not to say that this type of text-marking was the only function of the apex. Sometimes, it seems to have been used out of pure exuberance, and without consistency. An interesting case is the collection of letters Tab. Vindol. 243, 244, 248 and 291, all written by the same scribe. In 291, in the sections written by the scribe, almost every word-final vowel, whether long or short, receives an apex (only tuo is without): salutá, rogó, interuentú, and short /a/ in Seuerá (in the greeting formula) and facturá; in addition, f̣aciás has one on a non–word-final vowel (although in a final syllable; no apex is found on uenias, nos). In 243, a five word fragment, apices appear on suó (in the greeting formula) and fráter, but not on the long vowels of C̣eṛiạli or saluṭem. 244 uses no apices, although only the line Seuera mea uos salutat and the address Flauio Cerialị survive. The largely undamaged 248 uses an apex only on óptamus and tú, but not on the only examples of word-final /ɔ(ː)/ (suo, in the greeting, and pro; there are no examples of word-final /a(ː)/), nor on the other instance of op<t>amus, nor the two other instances of frater, which received an apex in 243.

By comparison, Tab. Vindol. 645 is a long letter, which fits much better than those written by the scribe of 243 etc. into the normal tendency at Vindolanda to use an apex on word-final /a(ː)/ and /ɔ(ː)/:Footnote 20 meó, gesseró, fussá, egó (twice), morá, s[[s]]ummá, Cocceịió, Maritimó (the last two in the address), and ịṭá (on a short /a/, if it is read correctly). According to the editors, the remaining instances of meo and of egọ may have had apices which were lost; otherwise in the main body of the letter only pro and opto remain without an apex on word-final /aː/ or /ɔː/, along with eo, quo in the postscript written between the columns, in which haste or space may have been a factor. There is also an apex on an initial vowel in uólui.Footnote 21

Although consistency within a single document or across all of a scribe’s output may not have been of great importance, the shared tendencies suggest that as a group the scribes of Vindolanda had developed their own habits of usage for apices.

In the tablets of the Sulpicii there are 76 instances of apices (Table 38).Footnote 1 27 of them are on personal names. In the TPSulp. tablets, as at Vindolanda, apices feature particularly in parts of the tablets written by the scribes (Reference CamodecaCamodeca 1999: 39): out of 76 instances of apices, 74 are found in scribal parts, with the remaining two coming from the chirographum of A. Castricius (deductá 81, repraesentátum 81). This divide between scribes, who use apices, and individual writers, who mostly do not, suggests a difference in education for the purpose of writing, as at Vindolanda.

Table 38 Apices in the tablets of the Sulpicii

| Apex | Text (TPSulp.) | Writer |

|---|---|---|

| Hósidio | 1 | Scribe |

| 1bis | Scribe |

| Faustó | 2 | Scribe |

| 3 | Scribe |

| 16 | Scribe |

| 18 | Scribe |

| noná | 19 | Scribe |

| 27 | Scribe |

| 32 | Scribe |

| Áug(–) | 33 | Scribe |

| 34 | Scribe |

| chalcidicó | 35 | Scribe |

| 40 | Scribe |

| 45 | Scribe |

| 47 | Scribe |

| 50 | Scribe |

| 51 | Scribe |

| Galló | 55 | Scribe |

| mé | 57 | Scribe |

| Alexándrì | 58 | Scribe |

| Áfro | 68 | Scribe |

| [Q]uártìónis | 77 | Scribe |

| 81 | A. Castricius |

| 82 | Scribe |

| Márius | 84 | Scribe |

| Tróphi | 110 | Scribe |

In the tablets of the Sulpicii, as at Vindolanda, a and o also make up a large percentage of all letters with apices (78%), as observed by Reference CamodecaCamodeca (1999: 39). But e and u make up a greater percentage of cases than at Vindolanda, and au and eu are also found with apices, unlike at Vindolanda (see Table 39).

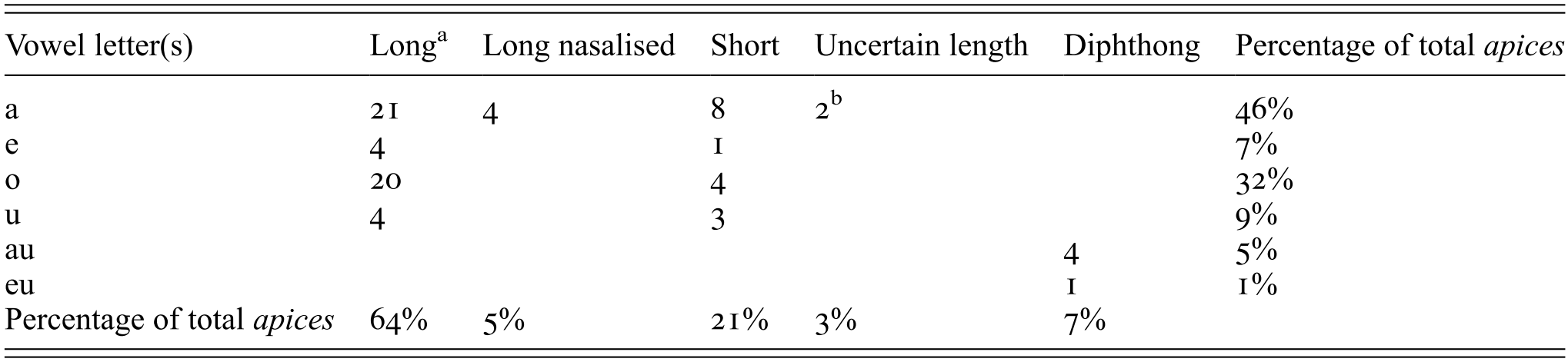

Table 39 Distribution of apices by vowels and diphthongs in the tablets of the Sulpicii

| Vowel letter(s) | LongFootnote a | Long nasalised | Short | Uncertain length | Diphthong | Percentage of total apices |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | 21 | 4 | 8 | 2Footnote b | 46% | |

| e | 4 | 1 | 7% | |||

| o | 20 | 4 | 32% | |||

| u | 4 | 3 | 9% | |||

| au | 4 | 5% | ||||

| eu | 1 | 1% | ||||

| Percentage of total apices | 64% | 5% | 21% | 3% | 7% |

a Including [aː] by lengthening before coda /r/ in [Q]uártìónis.

b There are two cases where I do not know the vowel length: the first vowels of Páctu[m]eìám, Pátulci.

The proportion of apices on long vowels is surprisingly small. I assume that originally long final vowels have not been shortened and that lengthening has taken place before coda /r/. Not including the two vowels of uncertain length this means that only 49/74 = 66% apices are on long vowels, with a further 5 on diphthongs. However, there are 4 instances of an apex on an originally short vowel in the accusative singular ending (acceptám 27, arám 16, [Ho]rdionianám 40, Páctu[m]eìám 40). This is likely to have become [ãː] before the first century AD (Reference AdamsAdams 2013: 128–32), and the scribes may have therefore considered it a long vowel. This takes us to 72% (53 apices on long vowels out of 74).

The final syllable is a favoured site for the apex, with 35/71 (49%) of relevant apices on a final syllable (there are also two monosyllables, and three abbreviations).Footnote 2 Reference CamodecaCamodeca (1999: 39) links this concentration on final syllables to Adams’ explanation of the preference for final position at Vindolanda as reflecting shortening of word-final long vowels. However, of these 35, 26 are on original word-final long vowels, 4 are on final /ãː/ represented by <am>, 4 are on long or short vowels followed by /s/, and only 1 is on a short vowel, the ablative nominé (3.2.7). There are 10 instances of an apex on long word-final /aː/ (not including [ãː]), and none on word-final /a/. This suggests that the scribes were able to tell these sounds apart; there is practically no evidence for shortening of final long vowels, so it seems unlikely that the placement of apices on final syllables is to be explained in this way.

Outside final syllables, the picture is much more mixed. Omitting monosyllables, and abbreviated names, and the 2 instances where I do not know the vowel length, there are 36 cases of an apex on a non-final syllable, of which 11 are on a short vowel, 2 on a diphthong and 21 on a long vowel (including the vowel in the first syllable of [Q]uártìónis). It is possible that there is a correlation here between stress and position of the apex, and the numbers of examples are slightly greater than at Vindolanda, which provides a little more confidence.Footnote 3 The key evidence for such a correlation is in short vowels, which do not in themselves draw the accent, as long vowels and diphthongs do. For the short vowels, 9/11 = 82% instances of the apex fall on the stressed syllable (exceptions are chirográphum, Hósidio);Footnote 4 this is suggestive of a correlation between stress and apex placement, although not completely conclusive, especially since regardless of the length of the vowel, the (initial) apex cannot be on a stressed vowel in Páctu[m]eìám and Pátulci. Including diphthongs and long vowels gives us a total of 27/36 = 75% of apices on non-final syllables that fall on stressed syllables.

However, this correlation does not provide evidence for lengthening of vowels in open syllables at this period, a change which took place on the way into Romance, and which may have already occurred by the third century AD in at least some varieties of Latin, with perhaps some occasional evidence for its occurrence earlier (Reference LoporcaroLoporcaro 2015: 18–60; Reference AdamsAdams 2013: 43–51, note in particular footnote 11). This is because, of the short vowels with an apex under the accent, only 6/9 are in an open syllable (ágitur, chirógraphum, háberet, Márius, Tróphi, D]ióg[e]nis vs Alexándrì, ánte, tánt[am]). So it looks as though, if the correlation with the accent is correct, it is the position of the accent that is being marked, rather than stressed long vowels. Within the word, only about a third of the examples of an apex occur on a long vowel. This may be due to a tendency to mark with an apex vowels or diphthongs which were stressed, regardless of whether they were long or not.

In conclusion, the scribes in the tablets of the Sulpicii tended to use apices in two different ways which are unique to them: in final syllables they were usually placed on long vowels (including long nasalised vowels); in non-final syllables they tended to be placed on stressed syllables.

As we have seen, the use of apices is characteristic of the writing of scribes in both the Vindolanda and TPSulp. tablets, but a fine-grained analysis highlights similarities and differences between the two corpora, and between them and the inscriptions studied by other scholars.

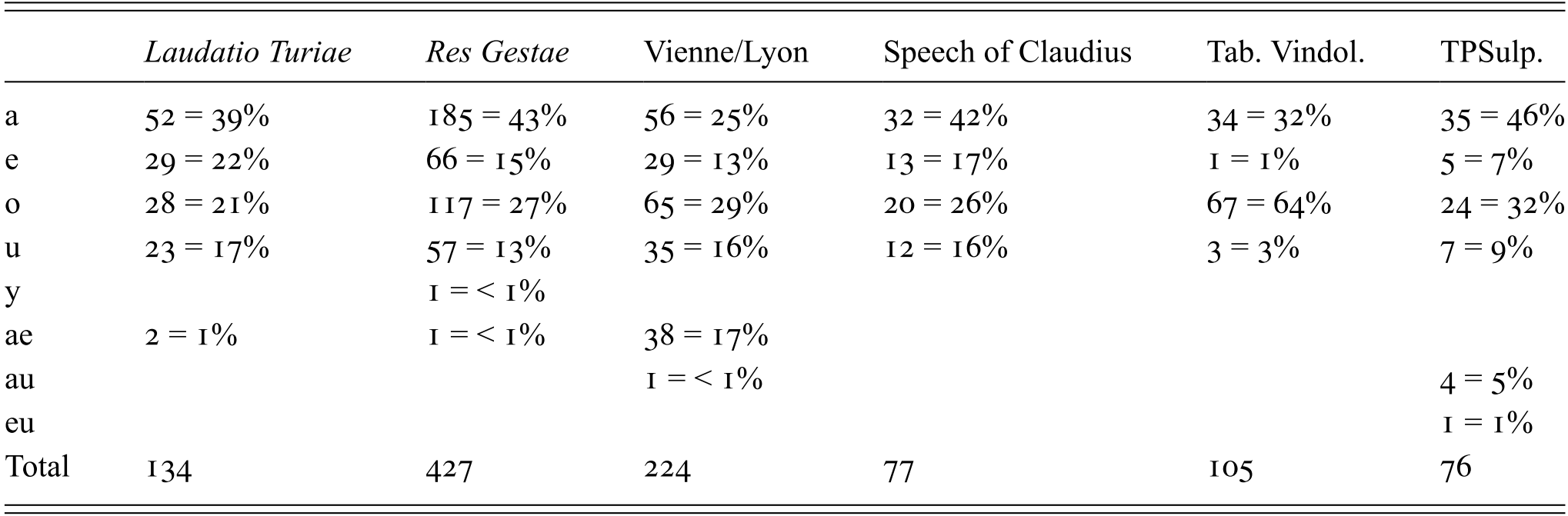

As shown by Table 40, in terms of the distribution of apices across all vowels, both the tablets of the Sulpicii and the Vindolanda tablets favour <a> and <o> compared to the inscriptional evidence collected by Reference Flobert and CalboliFlobert (1990) and Reference RolfeRolfe (1922),Footnote 1 which show a wide range from 54% (Vienne/Lyon) through 60% (Laudatio), 68% (speech of Claudius) to 70% (Res Gestae). TPSulp.’s ratio of 78% is not massively higher than that of Res Gestae, while Vindolanda’s is far greater at 96%. Vindolanda also has a preponderance of <ó> compared to <á>, whereas the Laudatio, Res Gestae, speech of Claudius, and TPSulp. have more <á> than <ó>, and the two are roughly equal in the Vienne/Lyon corpus.Footnote 2 Unsurprisingly, given the emphasis on <á> and <ó> at Vindolanda, no other corpus has such a restricted range of vowel types which bear an apex as Vindolanda.

Table 40 Apices in different corpora

| Laudatio Turiae | Res Gestae | Vienne/Lyon | Speech of Claudius | Tab. Vindol. | TPSulp. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | 52 = 39% | 185 = 43% | 56 = 25% | 32 = 42% | 34 = 32% | 35 = 46% |

| e | 29 = 22% | 66 = 15% | 29 = 13% | 13 = 17% | 1 = 1% | 5 = 7% |

| o | 28 = 21% | 117 = 27% | 65 = 29% | 20 = 26% | 67 = 64% | 24 = 32% |

| u | 23 = 17% | 57 = 13% | 35 = 16% | 12 = 16% | 3 = 3% | 7 = 9% |

| y | 1 = < 1% | |||||

| ae | 2 = 1% | 1 = < 1% | 38 = 17% | |||

| au | 1 = < 1% | 4 = 5% | ||||

| eu | 1 = 1% | |||||

| Total | 134 | 427 | 224 | 77 | 105 | 76 |

Presumably, these particular features of the Vindolanda tablets also partly reflect the text type and social context in which the letters were written: as we have already observed (see pp. 235–6), apices are particularly common in the address and greetings formulas of letters (33 out of 105 apices appear in these places, almost all on names). In these, ablatives and datives of the second declension feature very strongly, since most of the letters are sent by men to men; there are only two first declension names with an apex in a letter’s greeting or address: Seuerá (Tab. Vindol. 291), and -inná (324).

The proportion of apices which are actually on long vowels is smaller in the tablets of the Sulpicii at 72% than all the other corpora, although not far below that of the Vienne/Lyon corpus’s 75–77% and Vindolanda’s 82%;Footnote 3 in the official inscriptions practically all apices are on long vowels: speech of Claudius 100%; Laudatio Turiae 96%; Res Gestae 98%. Despite Vindolanda’s higher ratio of long vowels, I would suggest that this is an artefact of the scribes’ preference for word-final <a> and <o> as a site for the apex; this derives in part from generic and textual factors, rather than reflecting a preference for marking long vowels (see pp. 235–6).

At Vindolanda 79/100 = 79% of apices on polysyllables fall on the final syllable, while in the tablets of the Sulpicii the figure is much lower at 35/71 (49%). Again, the tablets of the Sulpicii are more similar to the pattern found in inscriptional evidence: in the Res Gestae 40% of apices are on long vowels or diphthongs at the end of a word, in the Laudatio of Turia 49%; in the corpus from Vienne and Lyon 52/203 = 26% of apices in polysyllabic words are on final syllables.Footnote 4 There are also notable differences in the type of final syllable which receives the apex in the tablets of the Sulpicii compared to those from Vindolanda. At Vindolanda, all but four apices in the final syllable are on a word-final vowel (75/79 = 95%; the exceptions are uoluerás, faciás, praecipiás, censús), most of which are /ɔː/. The favouring of word-final /ɔː/ as the site of the apex at Vindolanda may not be completely isolated in this regard. According to Reference RolfeRolfe (1922: 92), the dative and ablative ending in /ɔː/ is almost never given an apex in the Res Gestae but is frequent in other inscriptions.Footnote 5 In the tablets of the Sulpicii 27/35 = 77% of apices in polysyllables are on a word-final vowel. Assuming that final <am> counts as containing a long vowel, the 3 instances on nominative singulars in -us (Eunús twice in the same document, and Cinṇ[a]/mús), and nominé are the only exception to the rule that the apex in a final syllable of a polysyllabic word appears on a long vowel (31/35 = 89%) in TPSulp.

On the basis of these comparisons, in terms of which vowels receive an apex, and position in the word, both the Vindolanda tablets and those of the Sulpicii are fairly divergent from the other inscriptional corpora for which figures are available, although this is more pronounced with the Vindolanda tablets than with those of the Sulpicii (there is also an interesting tendency for the Vienne/Lyon inscriptions to differ from the long official inscriptions). The use of the apex by the scribes of the Sulpicii arguably comes closer to the advice of Quintilian than that of Vindolanda, in that first declension ablatives in long /aː/, which may receive the apex, are carefully distinguished from nominative singulars and neuter plurals ending in /a/, which may not. However, in both corpora (originally) long vowels are frequently given an apex even when this would not lead to confusion with any other word which differs only in the vowel length of one of its vowels. In this regard both corpora match with a more general disregard of the grammarians’ advice in epigraphic contexts (Reference RolfeRolfe 1922: 88, 92).

Both corpora are also characterised by a higher rate of apices being placed on short vowels (although long vowels are still greatly preferred). In the case of the Vindolanda tablets this seems to be the result of a determined placement of the apex on word-final <a> and <o> without regard to length. Where apices occur in non-final syllables, it is possible but not certain that this is the result of placement on the stressed syllable. In my view this is more likely in the TPSulp. tablets than at Vindolanda, where it is at least as likely that scribes tended simply to mark the vowel in an initial syllable.

Apart from these questions of which vowels, where in the word, receive the apex, we can also compare the corpora in terms of questions regarding positioning within larger units of texts. Within the letters they frequently seem to be used to mark out greeting and address sections from the rest of the letter, in common with letters as a genre from other places. This may interact with a more general feeling that names deserved to be marked out by the presence of an apex (as we have also seen in the Isola Sacra inscriptions, and has been suggested for other inscriptions; see p. 211 and Chapter 19). It is notable that a large proportion of the words with apices on them in both the Vindolanda and TPSulp. tablets are personal or place names. In the tablets of the Sulpicii, 30/76 (39%) of apices are on personal names, including all 5 instances of the apex on a diphthong (one the imperial name Augustus), and 9 out of 16 of the apices on a short vowel.

The wax tablets from Herculaneum, presenting a corpus very similar in use and purpose to that of the TPSulp. tablets, contain a very small number of apices, consisting of 16 instances on 14 words across 5 tablets (out of a total of 40 documents, including one copy). For the sake of completeness, I give all examples below this paragraph. 12 examples out of 16 are on long /aː/ and /ɔː/, 1 is on /ɔ/ arising by iambic shortening, 1 is on /ɔ/, 1 is on /ae̯/, and 1 is on /uː/. It is a remarkable coincidence that one of the words is pálós, one of the examples used by Quintilian of where an apex is appropriate. No overarching rationale for the use of apices arises, particularly given the extremely fragmentary material. Some instances are on personal or place names. In TH2 77 + 78 + 80 + 53 + 92, the sequence egó meós palo[s CCCXXX] caesós á te begins a record of direct speech which could be being marked off; but the same is not true of the other instances of apices in the text. We do find prepositional phrases receiving an apex on one or other of their members in á se, á te, and perhaps in contro]uersiá, but this still leaves pálós.

TH2 5 + 99, AD 60: suá

TH2 77 + 78 + 80 + 53 + 92, AD 69: á, pálós, contro]uersiá, egó, meós, caesós, á

TH2 61: Erastó, Pompeianó

TH2 A8, before AD 62–63: Calátório

TH2 A12, early 60s AD: factáe, Iúni Tḥeóphilì

The use of i-longa is very different from that of apices in the tablets of the Sulpicii and the tablets from Herculaneum. For one thing, i-longas are far more common than apices. In the TPSulp. tablets I count 799 instances of i-longa (compared to 76 apices), which appear in all but 16 of the 127 documents.Footnote 1 In the TH2 tablets they appear in 26 documents out of 40, and I count 243 instances in total. They also differ in the range of phonemes which they represent. Reference AdamsAdams (2013: 104–8) discusses the use of <ì> in the tablets of the Sulpicii at some length, although without a rigorous collection of examples. He observes that it is found for long /iː/ (as might be expected on the basis of the grammatical tradition), for short /i/, and for /j/, both word-initially and word-medially between vowels.Footnote 2 The large numbers of i-longa in the tablets of the Sulpicii make a full investigation difficult, but 163 cases are used to write a synchronic short vowel (with 19 of these being vowels which were originally long), which equates to 20% of the total.Footnote 3

The Herculaneum tablets contain 243 instances of i-longa, of which there are 209 instances of <ì> representing a long vowel,Footnote 4 5 cases where it represents a long vowel subsequently shortened,Footnote 5 14 where it represents an original short vowel,Footnote 6 8 representing /j/,Footnote 7 and 7 representing original /i/ in hiatus, for which it is uncertain whether this represents /i/ or /j/ (on which see fn. 2 and p. 292 fn. 2).Footnote 8 Combining original /i/ and /i/ as the result of shortening (but not /i/ in hiatus) gives us a proportion of 19/243 (8%). Clearly <ì> is used to represent /i/ much less frequently at Herculaneum than in the tablets of the Suplicii.Footnote 9

In the tablets of the Sulpicii, Adams suggests that <ì> seems to be used particularly often on long /iː/ (or /i/ which was originally long) when it comes at the end of the word, and also particularly on the initial /i(ː)/ of a word, even where the i is short, in both cases as a decorative device. The problem with these claims is that in order to know if i-longa is used more often in a particular position we need to be able to compare the cases both where i-longa is used and where it isn’t used. So, to assess whether i-longa is used particularly when word-final we would need to count all instances of (long) final /i(ː)/ which was written with and without i-longa (which would be a very large task) and compare this with all instances of long /iː/ which are not word-final (which would be an immense task). I do not intend to attempt this process, but I would observe that the number of instances of final /iː/ is likely to be very high in the tablets, both because it appears in a large number of Latin endings and because genitives of the second declension feature particularly heavily in the lists of witnesses. Thus, the fact that a large number of instances of i-longa appear word-finally may reflect the very high number of instances of word-final long /iː/ rather than a higher ratio of i-longa usage in this environment.

Along similar lines, it struck me at first sight that in the more manageable Herculaneum corpus the use of i-longa seemed to be greater in the lists of witnesses on the tablets than in other contexts. However, this is probably a reflection of the frequency of the second declension genitive singular in -ī in that context, rather than being due to a difference in the usage of i-longa. I count 138 instances of i-longa used to write gen. sg. in -ī in witness lists, versus 136 instances of it being written without i-longa (i.e. practically 50% of instances). In other parts of the tablets, I have found 25 instances of the gen. sg. with i-longa, and 21 without it, a distribution which suggests that there is no difference between use of i-longa in witness lists and elsewhere.Footnote 10

To give an idea of the usage of <ì> in the tablets of the Sulpicii, I have collected all examples of <ì> and <i> at the beginning of a word. This is achievable thanks to the excellent analytical indexes in Reference CamodecaCamodeca (1999). This allows me to compare the distribution of word-initial <ì> when used to represent long /iː/, short /i/, and /j/. There are 39 instances of initial long /iː/ written with <ì>, and a further 8 written with <i> (83%). There are 174 examples of initial /i/, of which 65 are written with <ì> (37%). There are 153 examples of initial /j/, of which 96 are written with <ì> (63%). From this we can conclude that the use of i-longa word-initially is not solely ornamental, since if so, we would expect an equal distribution of use among the categories. These figures suggest that <ì> is being systematically used to represent /iː/, but not /i/. Use of <ì> for /j/ is much more common than for /i/, but also notably less common than for /iː/. If someone were to count all examples of /i/ followed by a consonant vs /i/ in hiatus in the TPSulp. corpus, the distribution could be compared with these figures to ascertain whether <ì> was being used intentionally to represent /j/ arising from /i/ in hiatus.

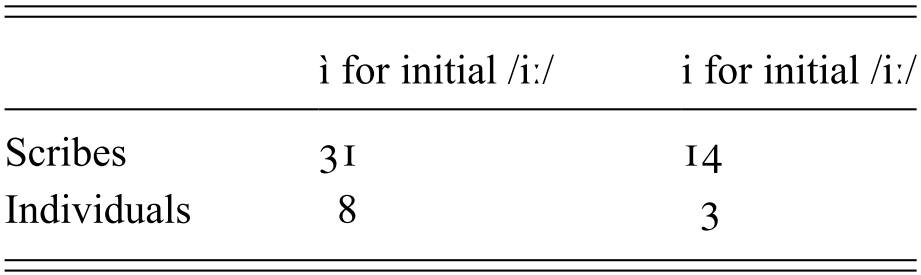

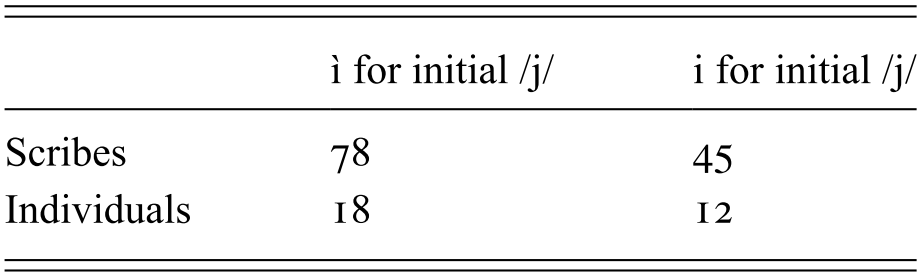

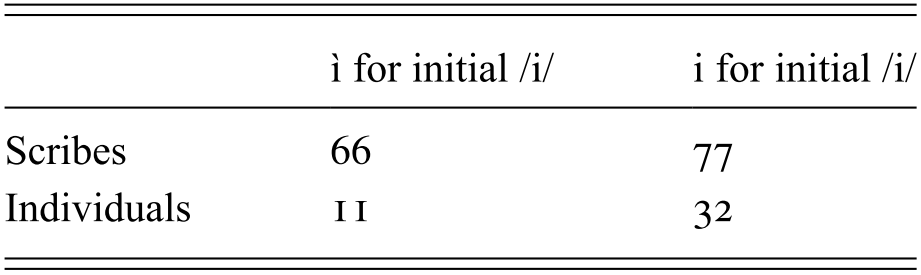

Since so many of the TPSulp. documents are chirographa, they allow us to test whether there is any significant difference in usage of i-longa between scribes and other individuals. The answer is yes: while there is no significant difference between scribes and other writers in use of <ì> to write /iː/ (Table 41) or /j/ (Table 42),Footnote 11 the scribes use <ì> to represent /i/ much more frequently than other writers (Table 43).Footnote 12

Table 41 Use of <ì> for /iː/ in the tablets of the Sulpicii

| ì for initial /iː/ | i for initial /iː/ | |

|---|---|---|

| Scribes | 31 | 14 |

| Individuals | 8 | 3 |

Table 42 Use of <ì> for /j/ in the tablets of the Sulpicii

| ì for initial /j/ | i for initial /j/ | |

|---|---|---|

| Scribes | 78 | 45 |

| Individuals | 18 | 12 |

Table 43 Use of <ì> for /i/ in the tablets of the Sulpicii

| ì for initial /i/ | i for initial /i/ | |

|---|---|---|

| Scribes | 66 | 77 |

| Individuals | 11 | 32 |

This suggests a difference in the practice (and hence, presumably, the training) of scribes and individuals: scribes appear to be trained to use i-longa for short word-initial /i/, about half the time, whereas individuals only do so a third of the time. The words with initial short /i/ marked with an i-longa consist of id, ideo, in (and its misspelling im) and words beginning with in-, ipso, is, Isochrysi, ita, italum and item. There is no clear correlation between use of the i-longa on a short vowel and stress in TPSulp.; these correlate in 80 instances out of 163.

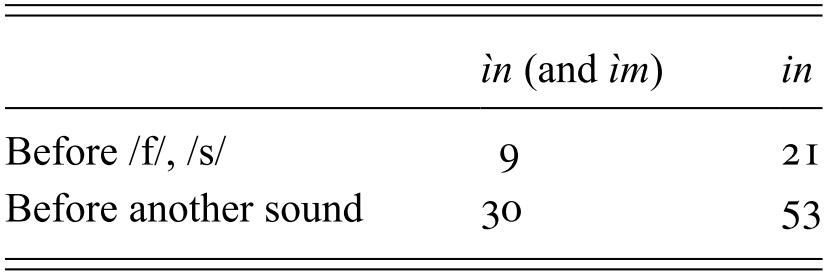

Given the very high amount of tokens of <ì> that consist of ìn and ìm (44 out of 77; all but 1 by scribes), I wondered whether there was some linguistic factor regarding in which could explain this distribution. Reference AllenAllen (1978: 65) notes that i-longa is found inscriptionally in sequences where in is followed by a word beginning with a fricative, where we would expect lengthening before nasal plus fricative clusters. But the tablets of the Sulpicii show no particular correlation between use of i-longa in in and a following fricative (Table 44).Footnote 13

Table 44 Use of ìn and in by following segment in the tablets of the Sulpicii

| ìn (and ìm) | in | |

|---|---|---|

| Before /f/, /s/ | 9 | 21 |

| Before another sound | 30 | 53 |

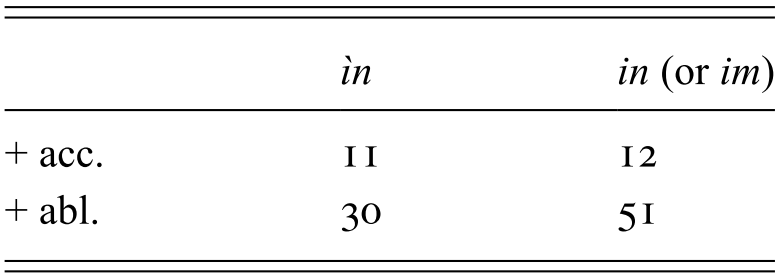

In the interests of completeness, I have also checked in the TPSulp. tablets whether there is any correlation between use and non-use of the i-longa in in and its differing semantics and case of its complement (Table 45).Footnote 14 Although ìn is found much more frequently followed by an accusative than by an ablative, no significant correlation is found.Footnote 15

Table 45 Use of ìn and in according to the case of its complement in the tablets of the Sulpicii

| ìn | in (or im) | |

|---|---|---|

| + acc. | 11 | 12 |

| + abl. | 30 | 51 |

Since I have found no linguistic factor which would explain the preponderance of i-longa used to write short <i>, it seems to me likely that scribes received training, or developed a practice amongst themselves, which encouraged them to use i-longa in this context, and especially in the word in. Adams may be right to see this practice as decorative, but in the light of the similar practices of the stonemasons of the Isola Sacra inscriptions (see Chapter 19) I suggest that the same reason applies: to increase legibility in a sequence of letters which involves several vertical strokes close together.Footnote 16

Other factors for use of <ì> on short /i/ might be similar to those found for apices, including a way of marking out names, and perhaps particularly imperial names. Reference Flobert and CalboliFlobert (1990: 106) observes in his corpus three examples of Tìb., stating ‘it is evidently a way to mark out the imperial praenomen carried by Tiberius and Claudius’ (c’est manifestement une façon de célébrer le prénom impérial porté par Tibère et Claude). In the tablets of the Sulpicii there are 28 examples of the abbreviation Tì for Tiberius, and only 5 of Ti., while in the Herculaneum tablets there are 8 of Tì. and 3 of Ti. A tendency for i-longa to be used in this abbreviation was also noted by Reference ChristiansenChristiansen (1889: 37–8).Footnote 17 However, I am not certain that this is due, as claimed by Flobert, to the celebrity of the emperors: it is the case that most, but not all, of the instances in the tablets of the Sulpicii refer to Tiberius or Claudius, who bore this name, while none of the instances at Herculaneum do. It is perhaps possible that the esteem attached to this name meant that the association of the abbreviation with i-longa spread to uses not referring to an emperor, and if so it must have lasted after Claudius’ death, since the tablets containing Tì. are mostly datable to the 60s AD. But it is also notable that the sequence TI is the kind in which lengthening of the <i> occurs for reasons of legibility in the Isola Sacra inscriptions.

One might even wonder if there could be more localised reasons for use of i-longa in some cases. In TPSulp. 45, the chirographum of one Diognetus, slave of C. Novius Cypaerus, we find (along with a number of other substandard spellings) ube for ubi ‘where’ and legumenum for leguminum ‘of pulses’ as a result of the falling together of /i/ and /eː/. In the scribal portion of the text these words are spelt ubì and legumìnum. Is it possible that the scribe reacted to Diognetus’ misspellings by emphasising the correct vowel with an i-longa?Footnote 18

Old-Fashioned Spelling? Problems and Different Histories

A key result which arises from my investigation is that treating old-fashioned spelling as a single category is not a particularly useful approach. More nuance is required, since the history, development and survival or loss of individual spelling rules and individual lexemes are highly varied and depend on a number of factors.

A good example of the complexities that arise with the concept of old-fashioned spelling is the use of the digraph <xs> for /ks/ (Chapter 14). The methods I have used to decide whether a spelling is old-fashioned (pp. 10–15) give different results: it seems always to have been less commonly used than <x> from its creation in the third or early second century BC until the fourth century AD, so we cannot talk about an absolute change in frequency; and the writers on language deprecate it without suggesting, as they do for other spellings, that they consider it old-fashioned. The major change seems to have been in register and/or social or educational background, with <xs> first appearing in Latin epigraphy in the SC de Bacchanalibus of 186 BC, but largely falling out of use in official texts by the first century BC. However, it appears to be part of the training of the scribes of the Caecilius Jucundus archive, is the majority usage in the tablets from London and continues to be used into the second century in texts (perhaps especially letters?) at Vindolanda, and into the fourth century in the curse tablets.

Similarly problematic is the case of the variation between <u> and <i> between /l/ and a labial plosive, and before a labial consonant in non-initial syllables (Chapter 6), where the move to the <i> spelling, and hence the old-fashionedness, varies according to individual lexemes and morphological categories. For example, the <i> spelling is utterly dominant in the root lub- from the first century AD onwards, while clupeus competes with clipeus into the second century AD. In the first to fourth centuries AD, superlatives in -issimus massively favoured <i>, while proximus and optimus used <u> respectively 10% and 9% of the time, and postumus had <u> 96% of the time. Of the ordinals, septimus has <u> 5% of the time, but decimus 19%.

When a move from an older to a more innovative spelling occurs due to phonological change, sometimes the new spelling quickly becomes standard and apparently almost entirely replaces the older spelling. An example of this is the change from <uo> to <ue> before a coronal obstruent or syllable-final /r/ (Chapter 7): the newer spelling is not found until the final quarter of the second century BC, but is already dominant in the first century BC, and is almost never found after that except in highly archaising verse inscriptions, in the word diuortia, and in the divine name Vortumnus. Some spellings are found infrequently or not at all in the corpora, for example preservation of <oe> (/ɔi/ > /uː/ in the fourth century BC; see p. 40), <ai> (/ai/ > /ae̯/ in the second century BC; Chapter 2), <o> for /u/ (various sound changes in the third and second centuries BC; Chapter 5), <c> for /g/ (invention of <g> in the third century BC; Chapter 10), and the use of double writing of vowels to represent length, which came into use in the mid-second century BC but fell out of use fairly quickly (Chapter 9).

In other cases, the older spelling is maintained much longer, both in elite and sub-elite contexts. An example of this is the use of <uo> for /wu/ (Chapter 8). In part this reflects the later occurrence of the sound change /wɔ/ > /wu/ which led to the innovatory spelling <uu>, since this probably did not take place until the mid-first century BC; in part it also reflects the fact that the <uo> spelling allowed the maintenance of a useful distinction between two different phonological sequences, whereby /wu/, spelt <uo>, could be kept separate from /uu/, spelt <uu>. This spelling rule is found over a large geographical range (Pompeii, Vindolanda, Egypt), and was maintained at least until the early second century in my corpora; at Vindolanda it was shared by the equestrian prefect Cerialis, scribes, and substandard spellers. The <uo> spelling for /wu/ is attested epigraphically as late as the fourth century AD, including fairly robustly into the second century AD in ‘official’ inscriptions.

Unlike sound change, spelling does not change in a way that is either regular or exceptionless. Certain lexemes may favour or resist innovatory spellings. I have already mentioned the lexical variation in the <u> / <i> interchange. Another example is the use of double <ll> in millia ‘thousands’, which was maintained as the standard spelling well into the first century AD, both in the epigraphic record generally and in the sub-elite corpora examined here, despite the fact that the phonological change to single /l/ had taken place by the mid-first century BC, and other words, such as uīlicus, are usually spelt with a single <l>. This can also compare with the similar reduction of /ss/ to /s/ after a long vowel or diphthong, which took place about the same time (Chapter 15). The tablets of the Sulpicii, which massively favour the <ll> spelling in millia, millibus, also heavily prefer <s> to <ss> in most words, although caussa may be preferred to causa. Nonetheless, use of <ss> also shows signs of survival for a long time, with several examples in curse tablets from Britain in the third and fourth centuries AD.

Another spelling whose survival was closely connected to particular lexemes was the use of <qu> to represent /k/ before a back vowel (Chapter 13). Original /kw/ had lost its labiality in the third century BC, but <qu> was preserved in the corpora into the first century or early second century AD in quom for cum ‘when’ and quur for cūr ‘why’, and it is identified in these words by the writers on language into the fourth century AD (who, however, recommend the artificial quum for cum).