As we have seen, the use of apices is characteristic of the writing of scribes in both the Vindolanda and TPSulp. tablets, but a fine-grained analysis highlights similarities and differences between the two corpora, and between them and the inscriptions studied by other scholars.

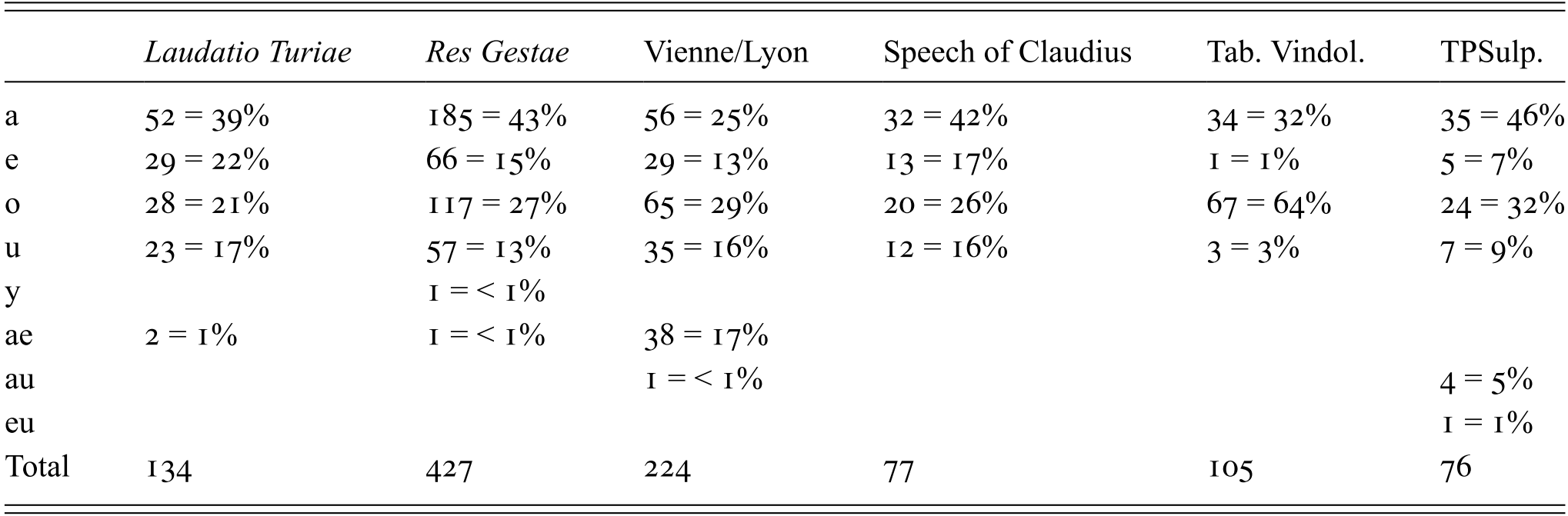

As shown by Table 40, in terms of the distribution of apices across all vowels, both the tablets of the Sulpicii and the Vindolanda tablets favour <a> and <o> compared to the inscriptional evidence collected by Reference Flobert and CalboliFlobert (1990) and Reference RolfeRolfe (1922),Footnote 1 which show a wide range from 54% (Vienne/Lyon) through 60% (Laudatio), 68% (speech of Claudius) to 70% (Res Gestae). TPSulp.’s ratio of 78% is not massively higher than that of Res Gestae, while Vindolanda’s is far greater at 96%. Vindolanda also has a preponderance of <ó> compared to <á>, whereas the Laudatio, Res Gestae, speech of Claudius, and TPSulp. have more <á> than <ó>, and the two are roughly equal in the Vienne/Lyon corpus.Footnote 2 Unsurprisingly, given the emphasis on <á> and <ó> at Vindolanda, no other corpus has such a restricted range of vowel types which bear an apex as Vindolanda.

Table 40 Apices in different corpora

| Laudatio Turiae | Res Gestae | Vienne/Lyon | Speech of Claudius | Tab. Vindol. | TPSulp. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | 52 = 39% | 185 = 43% | 56 = 25% | 32 = 42% | 34 = 32% | 35 = 46% |

| e | 29 = 22% | 66 = 15% | 29 = 13% | 13 = 17% | 1 = 1% | 5 = 7% |

| o | 28 = 21% | 117 = 27% | 65 = 29% | 20 = 26% | 67 = 64% | 24 = 32% |

| u | 23 = 17% | 57 = 13% | 35 = 16% | 12 = 16% | 3 = 3% | 7 = 9% |

| y | 1 = < 1% | |||||

| ae | 2 = 1% | 1 = < 1% | 38 = 17% | |||

| au | 1 = < 1% | 4 = 5% | ||||

| eu | 1 = 1% | |||||

| Total | 134 | 427 | 224 | 77 | 105 | 76 |

Presumably, these particular features of the Vindolanda tablets also partly reflect the text type and social context in which the letters were written: as we have already observed (see pp. 235–6), apices are particularly common in the address and greetings formulas of letters (33 out of 105 apices appear in these places, almost all on names). In these, ablatives and datives of the second declension feature very strongly, since most of the letters are sent by men to men; there are only two first declension names with an apex in a letter’s greeting or address: Seuerá (Tab. Vindol. 291), and -inná (324).

The proportion of apices which are actually on long vowels is smaller in the tablets of the Sulpicii at 72% than all the other corpora, although not far below that of the Vienne/Lyon corpus’s 75–77% and Vindolanda’s 82%;Footnote 3 in the official inscriptions practically all apices are on long vowels: speech of Claudius 100%; Laudatio Turiae 96%; Res Gestae 98%. Despite Vindolanda’s higher ratio of long vowels, I would suggest that this is an artefact of the scribes’ preference for word-final <a> and <o> as a site for the apex; this derives in part from generic and textual factors, rather than reflecting a preference for marking long vowels (see pp. 235–6).

At Vindolanda 79/100 = 79% of apices on polysyllables fall on the final syllable, while in the tablets of the Sulpicii the figure is much lower at 35/71 (49%). Again, the tablets of the Sulpicii are more similar to the pattern found in inscriptional evidence: in the Res Gestae 40% of apices are on long vowels or diphthongs at the end of a word, in the Laudatio of Turia 49%; in the corpus from Vienne and Lyon 52/203 = 26% of apices in polysyllabic words are on final syllables.Footnote 4 There are also notable differences in the type of final syllable which receives the apex in the tablets of the Sulpicii compared to those from Vindolanda. At Vindolanda, all but four apices in the final syllable are on a word-final vowel (75/79 = 95%; the exceptions are uoluerás, faciás, praecipiás, censús), most of which are /ɔː/. The favouring of word-final /ɔː/ as the site of the apex at Vindolanda may not be completely isolated in this regard. According to Reference RolfeRolfe (1922: 92), the dative and ablative ending in /ɔː/ is almost never given an apex in the Res Gestae but is frequent in other inscriptions.Footnote 5 In the tablets of the Sulpicii 27/35 = 77% of apices in polysyllables are on a word-final vowel. Assuming that final <am> counts as containing a long vowel, the 3 instances on nominative singulars in -us (Eunús twice in the same document, and Cinṇ[a]/mús), and nominé are the only exception to the rule that the apex in a final syllable of a polysyllabic word appears on a long vowel (31/35 = 89%) in TPSulp.

On the basis of these comparisons, in terms of which vowels receive an apex, and position in the word, both the Vindolanda tablets and those of the Sulpicii are fairly divergent from the other inscriptional corpora for which figures are available, although this is more pronounced with the Vindolanda tablets than with those of the Sulpicii (there is also an interesting tendency for the Vienne/Lyon inscriptions to differ from the long official inscriptions). The use of the apex by the scribes of the Sulpicii arguably comes closer to the advice of Quintilian than that of Vindolanda, in that first declension ablatives in long /aː/, which may receive the apex, are carefully distinguished from nominative singulars and neuter plurals ending in /a/, which may not. However, in both corpora (originally) long vowels are frequently given an apex even when this would not lead to confusion with any other word which differs only in the vowel length of one of its vowels. In this regard both corpora match with a more general disregard of the grammarians’ advice in epigraphic contexts (Reference RolfeRolfe 1922: 88, 92).

Both corpora are also characterised by a higher rate of apices being placed on short vowels (although long vowels are still greatly preferred). In the case of the Vindolanda tablets this seems to be the result of a determined placement of the apex on word-final <a> and <o> without regard to length. Where apices occur in non-final syllables, it is possible but not certain that this is the result of placement on the stressed syllable. In my view this is more likely in the TPSulp. tablets than at Vindolanda, where it is at least as likely that scribes tended simply to mark the vowel in an initial syllable.

Apart from these questions of which vowels, where in the word, receive the apex, we can also compare the corpora in terms of questions regarding positioning within larger units of texts. Within the letters they frequently seem to be used to mark out greeting and address sections from the rest of the letter, in common with letters as a genre from other places. This may interact with a more general feeling that names deserved to be marked out by the presence of an apex (as we have also seen in the Isola Sacra inscriptions, and has been suggested for other inscriptions; see p. 211 and Chapter 19). It is notable that a large proportion of the words with apices on them in both the Vindolanda and TPSulp. tablets are personal or place names. In the tablets of the Sulpicii, 30/76 (39%) of apices are on personal names, including all 5 instances of the apex on a diphthong (one the imperial name Augustus), and 9 out of 16 of the apices on a short vowel.