2 When broad networks increase cooperation

Firms are the basic unit of capitalism, yet political science has only begun to study the role of firm governance on the construction of institutions in emergent capitalist economies, such as corporate governance law, contract and transaction law, property rights, financial institutions and access to credit, tax codes, and trading structures. Individual firms each have their own means and goals, but rarely do they have sufficient influence to choose policies alone.

My argument is that the extent to which firms can coordinate their actions to achieve political goals has a strong effect on the trajectory of institutional development. Part III situates business collective action within varying levels of political uncertainty. First, however, Part II seeks to understand what shapes the incentives of firms to act together instead of trying to pursue political preferences alone. This requires the mapping of both incentives for and obstacles to joint political action. Following on the previous chapter, my view is that firm collective action depends on the ability of firms and their directors to overcome problems, establish trust and frame common goals. Focusing on the networks of ownership ties between firms, I show here that the likelihood of collective action rises when networks are broad because shared ownership among firms is a basis for credible commitments among firms on issues, such as political action, on which contracting agreements is impossible (Williamson Reference Williamson1985: 166).

The interactions of economic and political elites likely have one broad goal: all actors seek influence in order to shape regulatory and bureaucratic decisions, and choices regarding the development of institutions, in their own favor. A long-standing body of work argues, in line with Olson’s seminal point, that entrenched, wealthy insiders pursue rent-seeking activities to preserve the status quo (Olson Reference Olson1963; Krueger Reference Krueger1974; Olson Reference Olson1982; Veblen Reference Veblen1994 [1899]; Morck, Strangeland, and Yeung Reference Morck, Strangeland, Yeung and Morck2000; Olson Reference Olson2000; Rajan and Zingales Reference Rajan and Zingales2003). My argument, to the contrary, is that firms do not have a single set of interests. Instead, firm preferences and demands depend heavily on the network structure of a particular economy. I show that, when the ownership structure is broad, more collective action ensues than when a narrow ownership structure is present.

Ownership structure is a key variable in this argument because different forms of ownership are matched by different opportunities for owners to exert influence and control (Kogut Reference Kogut and Kogut2012: 12–15, 20–23) (Windolf Reference Windolf1998). Hence, whether ownership is broad or narrow will have a determining effect on the emergence of joint action. The types of actors that inhabit important positions in a given network determine the dominant structure of ownership that emerges. To take just two examples, as is explained below, banks and institutional investors are more likely to create broader, more horizontal structures, while industrial and family firms favor the opposite.

Other networks – personnel ties between firms, overlapping career paths, and joint membership in organizations – also have an important impact on the ability of individuals and their respective organizations to engage in collective action. While ownership networks provide a structural view of polity–economy ties, career networks provide the individual-level perspective and are analyzed in later chapters. At the structural level, ownership networks are the key ties that link firms and structure the payoffs of collaboration between firms. Ownership networks are often seen as the basis under which credible commitments among firms are possible in conditions in which formal contracting of agreements is unavailable.1 Williamson (Reference Williamson1985: 167) defines credible commitments as “reciprocal acts designed to safeguard a relationship” involving “irreversible, specialized investments.” Moreover, ownership networks create the basis for other forms of connection, such as the sharing of directors on boards.

It is also important to note that firms that exercise influence on political actors are neither exceptional nor limited to state-owned firms that are unable to adapt to the new rigors of the market economy. According to the EBRD’s “Business environment and enterprise performance survey” (BEEPS) (EBRD 2005b) of firms across the Baltics, central and southern Europe, and the Commonwealth of Independent States, firm involvement with the state is much more common than what may be expected in what are frequently believed to be competitive markets that have passed through two decades of reform and are populated by mostly privatized firms. The transformation of socialist economies is often believed to have separated the economy from politics. Instead, survey data show that the economy continues to be deeply enmeshed in politics, but the nature of this connection varies across countries.

In the extreme version, firms seek to engage in direct one-to-one influence of state actors, known as state capture. The dynamics of state capture run counter to the usual expectation that weak uncompetitive firms seek influence to compensate for their inability to compete in the marketplace. To the contrary, survey evidence finds that larger firms often attempt to influence policy and also engage in state capture – when vested interests exert an excessive influence on the state – more than do small firms (EBRD 2005a: 90). This is also true of foreign-owned and exporting firms, which are often believed to be less interested in domestic politics and regulatory decisions and less involved in seeking influence. Moreover, firms operating in competitive markets have been more active in attempting to intervene than monopolists, suggesting that it is precisely the pressure of competition that leads firms to seek political influence. Finally, firms with higher investment rates tend to be more likely to engage in state capture (EBRD 2005a: 90), countering the belief that only the uncompetitive behemoths of state socialism still rely on protection and influence. The EBRD Transition Report 2005 indicates that attempts at state capture tend to originate from better-performing firms, rather than firms struggling to survive. And these better-performing firms have a significant impact on the constraints facing other firms, with the strongest effect in the area of tax administration (EBRD 2005a: 90–1).

How, then, do the structures of ownership create opportunities for firms to cooperate in designing the trajectory of institutional development and mitigate the temptation for firms to exercise direct influence? This chapter answers the question by drawing on a broad literature on corporate governance that discusses the opportunities and agency problems that arise for firms with various forms of ownership. My argument is that broad networks of ownership raise the likelihood of collective action because they promote firm cooperation. The network structure of ownership reflects the distribution of control over firms in the economy.

The classic problem of corporate governance has been formulated by Berle and Means (Reference Berle and Means1991) as the separation of ownership and control. When ownership and control are separated, owners suddenly face a problem of agency. The “agency problem” refers to the difficulty that financiers have in monitoring and influencing how their funds are used. Not only do they face classic principal–agent monitoring problems, but they also face voting constraints if they are minority stakeholders. In other words, as large shareholders who are able to alienate minority shareholders become more prominent in a given economy, agency problems become more pronounced. Scholarship interested in the separation of ownership and control has typically focused on the challenges of governance generated within a firm. If firms are also considered political actors, however, then these agency problems can be scaled up to the level of market governance. Agency problems aggregated to the national level make it possible for a small group to be influential because of its control rights of capital, despite the ownership rights held by others who are in a minority in each firm. Building on this intuition, the agency problem defined by Berle and Means provides a foundation on which to construct an understanding of firms’ political action.

This approach departs from existing studies of firm political preferences, which have focused on variables that capture the macro-distribution of actors in an economy: asset specificity, the size of the export sector, employer coordination, the tradition of guilds, and employer–worker relations (Frieden Reference Frieden1988; Rogowski Reference Rogowski1989; Crouch and Brown Reference Crouch and Brown1993; Milner Reference Milner1997; Mares Reference Mares2003; Thelen Reference Thelen2004). Instead, I consider ownership structure as the lever by which coordination for political purposes can take place among firms, and in so doing I draw on insights from the literature on corporate governance to complement existing studies of business sectoral negotiation over policy choice that tend to focus mostly on sectoral (import versus export) or class (employers versus unions) conflicts rather than on the level of the individual firm.

Not surprisingly, forms of capitalism vary widely in how ownership and control are configured. They also differ sharply on what types of firms are most prominent. For example, in industrial capitalism, commodity-producing firms are the key owners of other firms. In institutional or financial capitalism, in which financial firms predominantly own other firms and the commodity-producing firm is in itself a commodity, large institutions are the key power holders (Windolf Reference Windolf1998). Pension funds and investment banks hold key positions in the framework of economic power and have different interests and goals from industrial firms. In yet another variant, managerial capitalism, the power of managers rests on the underlying wide distribution of ownership. In each variant, shares of control over firms are distributed differently. The next sections discuss the interests of different types of firms. Following these sections, a framework is developed to link firm types to the various problems of coordination that emerge when networks include homogeneous versus heterogeneous firms.

Actors and interests

Olson and others have made the argument that greater control of economic resources translates into greater political power, which can be used to shape institutions in the future toward the goals of those in power. This link thus presents, they argue, an economic incumbency effect (Olson Reference Olson2000; Morck and Yeung Reference Morck and Yeung2004; Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson Reference Acemoglu, Johnson, Robinson, Aghion and Durlauf2005). The authority structure of a firm decides who can lay claim to the cash flow. Hence, corporate governance affects wealth creation and distribution, the fate of suppliers and distributors, the fortunes of pension funds and retirees, and the endowments of charitable institutions (Gourevitch and Shinn Reference Gourevitch and Shinn2005). And the distribution of political resources via lobbying affects who wins elections and what policy options are chosen. Further, “the players in the firm, as they turn to politics to get the regulations they prefer, have to appeal to a broad set of external stakeholders” through the system of political institutions (Gourevitch and Shinn Reference Gourevitch and Shinn2005: 10). The size of this external stakeholder group will differ as the ratio of small shareholders to large shareholders changes.

Whether small or large shareholders dominate will affect the choice of political institutions. For example, the concentration of ownership and control are related to the basic features of a country’s legal system, and in particular to the choice of minority shareholder protections (LaPorta, Lopez-de-Silanes, and Shleifer Reference Laporta, Lopez-de-Silanes and Shleifer1999). In other words, other scholars have identified how ownership distribution and corporate governance are critical components shaping the political economy and the link between firms and political outcomes.

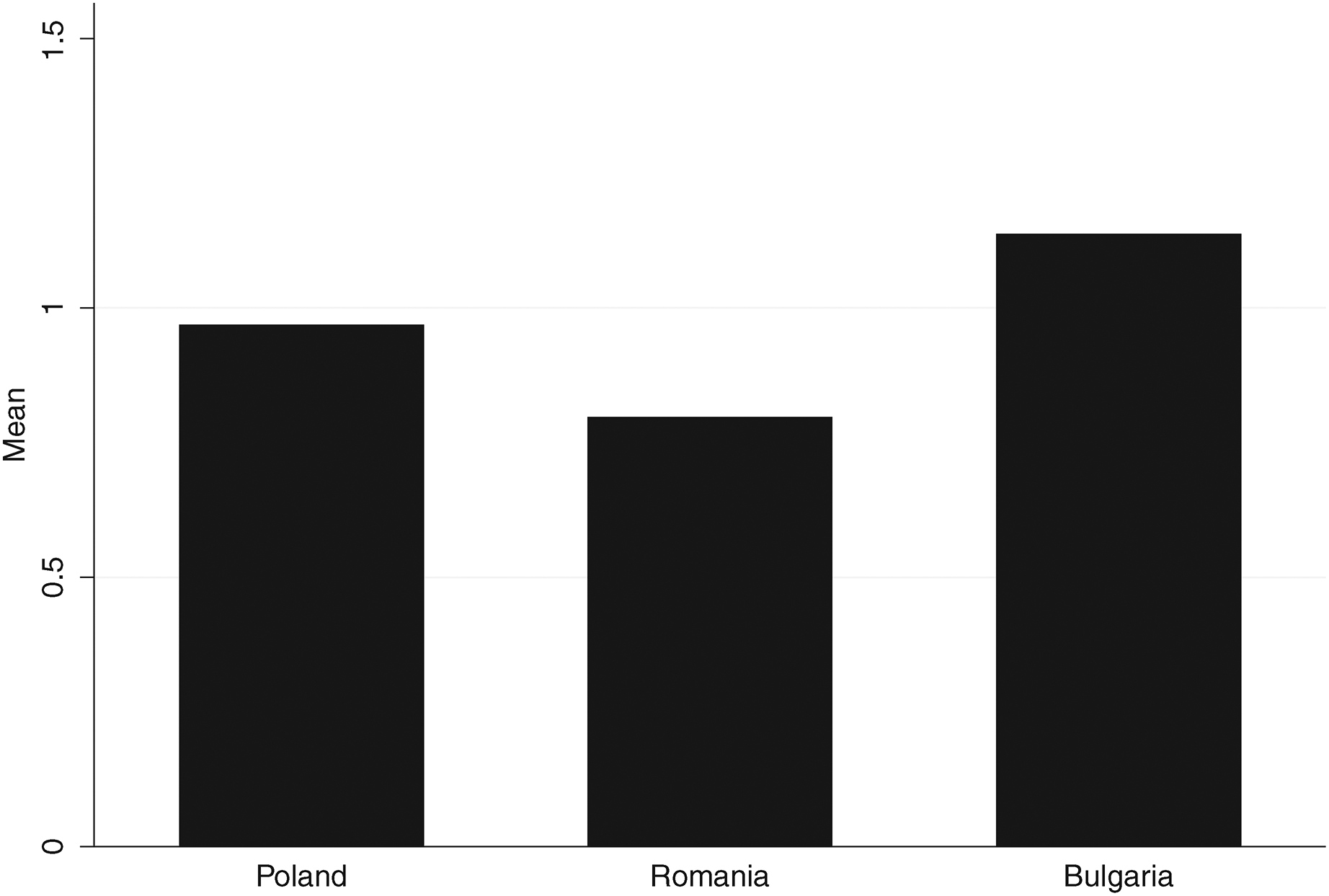

Table 2.1 shows variation in ownership concentration by comparing the average number of largest shareholders in a firm in each country under examination. Firms were asked to report the number of shareholders holding the largest packet of shares. Poland has the highest number, indicating that ownership is spread across a relatively high number of stakeholders. Bulgaria is significantly lower, and Romania has the lowest value. In the latter, larger shareholders dominate. The variation here is sufficient to lead us to expect very different types of coalition forming among firms.

The prominence of small and large shareholders is not the only factor that affects the macro-structure of ownership. Owners in a firm vary also by how likely they are to hold shares in only a single other firm, in a set of firms in a particular sector of the economy, or in a broad assortment of firms. For example, banks and financial firms are more likely to have an interest in many different types of firms as part of a portfolio of diverse investments. Industrial or family firms tend to hold stakes in fewer firms and will often vertically integrate other firms in supply chains. Thus, when banks are prominent, networks will be broader, and this raises the likelihood of collective action. Because banks and financial firms have an ownership interest in a much more diverse group of firms, I hypothesize that banks are more likely to lobby for broadly conceived rather than narrowly distributive institutions.

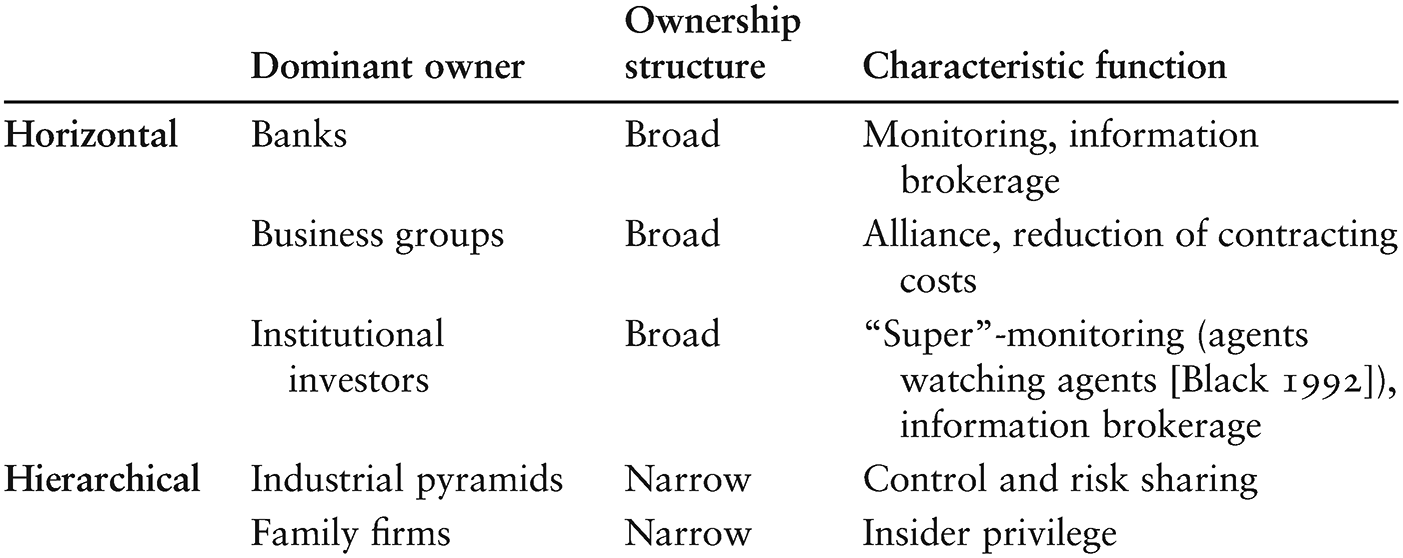

The cases analyzed later in this chapter therefore examine the form of owner (or combination of owners) that dominates: bank, institutional investor, state, industrial, or family. Broad and narrow networks each impart a different flavor to the broader behavior of firms in a particular political economy, as each owner type can perform a different characteristic function. These are shown in Table 2.2 and explained in more detail below. Broad ownership indicates that there are many smaller shareholders and firms widely connected to each other. Narrow ownership means that large block holders dominate.

Table 2.2 Owners, ownership structures, and resulting functions

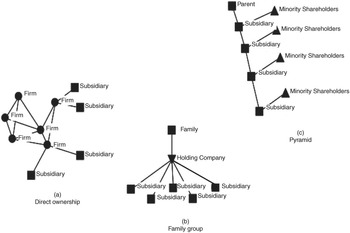

As shown in Table 2.2, owner types can be divided into two categories: those that promote a horizontal structure by virtue of their direct ownership of many firms (see Figure 2.1a) and those that promote a hierarchical structure, such as family groups and business pyramids (see Figures 2.1b and 2.1c). Banks and institutional investors, for example, will tend to acquire stakes across sectors to spread risk across a portfolio. These firms will sometimes seek input in firm governance but are less likely to own controlling shares. By contrast, owners that promote a hierarchical structure will tend to value control.

Figure 2.1 Ownership structures

Table 2.2 also illustrates how each type performs a different characteristic function. Banks and institutional investors serve as information conduits and facilitate monitoring (Useem Reference Useem1984; Mintz and Schwartz Reference Mintz and Schwartz1985; Davis and Mizruchi Reference Davis and Mizruchi1999). Business groups reduce contracting costs and facilitate alliances (Gilson and Roe Reference Gilson and Roe1993). In contrast, the two hierarchical types that create narrow networks protect and retain control for insiders while facilitating risk sharing with minority shareholders (Rajan and Zingales Reference Rajan and Zingales2003).

Each form affects how control votes of firms are aggregated in the economy and spreads risk differently at the macro level of the economy. Family pyramids, for example, tend and often seek to alienate small shareholders while benefiting from the use of their capital. Institutional investors, by contrast, promote the interests of diffuse shareholders as intermediaries by virtue of the fact that, when these investors are prominent, they mediate between a large economy of shareholders and the firms that are the target of their investment.

What are the advantages of each form? Each structure provides a different solution to the problem of ownership and control in contexts in which risk is high and financial resources are scarce. The pure hierarchical structure (Figure 2.1b) joins both ownership and control: those possessing funds have full control of the firm(s). The pyramidal structure (Figure 2.1c) separates minority owners from control of the firm. A range of intermediate outcomes are possible, for example when multiple, cross-cutting ties link firms (Figure 2.1a), with the possibility of reciprocal holdings of shares among a group of firms such that mutual ownership blurs the lines of ownership and control but can reinforce alliances between firms (Gerlach Reference Gerlach1992). This last type can be either loosely or tightly connected.

The question of ownership and control in its classic form has focused on management issues that arise when managers are separated from owners. Different structures of ownership also offer owners different access to the resources of firms in a group, however (Perotti and Gelfer Reference Perotti and Gelfer2001). Whether a business group will add a firm in a pyramidal or direct (horizontal) fashion depends on the business environment. Loose horizontal ties are viable when coalition governance is possible and trust is high. In periods of financial distress, instead, collective action can become more difficult. As coalition-enforced threats become less credible, hierarchical control is preferred (Berglof and Perotti Reference Berglof and Perotti1994).

Different structures also allow owners to benefit to varying extents from the cash flow of the firm. Ownership in a structure in which the family takes on direct ownership of the new firm (as in Figure 2.1b) is preferred when the controlling shareholder does not wish to share any of the cash flow rights of any firm in the group with other shareholders, as it would in the pyramidal structure. The drawback is that, in creating new firms, the controlling shareholder has access only to its retained cash flow in the original firm but receives all the benefits and costs from the new firm (Almeida and Wolfenzon Reference Almeida and Wolfenzon2006). By contrast, pyramids allow the already established firms in the group to finance the acquisition or creation of new firms with capital belonging to minority shareholders higher up in the pyramid.

Hence, network structure is a direct reflection of the level of cooperation that is possible among holders of capital. More hierarchical structures make collective action among firms less likely, while more dispersed structures raise the likelihood that firms can collectively agree on the structure of institutions.

One feature that determines the structure of ownership in the economy is the identity of owners. Some owners will tend to promote certain kinds of structures. For example, if financial institutions dominate, then the structure of the economy will tend to be more horizontal, as funds and banks invest in firms and in each other. When families dominate, a more hierarchical structure will tend to emerge. The next sections explain how the identities of owners impact the macroeconomy by tracing the incentives generated by different types of horizontal and vertical owners. Based on an analysis of these types, I argue that horizontal structures raise the likelihood of collective action among firms.

Horizontal

Three types of horizontal owners – banks, business groups, and institutional investors – raise the likelihood of collective action.

Banks

How does the presence of prominent banks in the ownership structure influence governance? Banks facilitate finance, information sharing, contracting, bargaining, and political cohesion among firms.

Bank prominence in networks of ownership channels capital and anchors the social organization of business (Mintz and Schwartz Reference Mintz and Schwartz1981; Mintz and Schwartz Reference Mintz and Schwartz1983; Davis and Mizruchi Reference Davis and Mizruchi1999). Although in the US case banks own a large share of US firms, they rarely seem to have used their power to control management directly. Banks are able to influence firms broadly, however, because of their control of funds and access to short-term loans (Mintz and Schwartz Reference Mintz and Schwartz1983), particularly in hard times when capital is in short supply (Davis and Mizruchi Reference Davis and Mizruchi1999). Banks can particularly constrain the behavior of firms during contraction periods and thus affect the direction an economy takes toward the next upswing (Davis and Mizruchi Reference Davis and Mizruchi1999). Firms that have a director of a financial institution on their board are much more likely to borrow than those without such ties (Stearns and Mizruchi Reference Stearns and Mizruchi1993; Mizruchi and Stearns Reference Mizruchi and Stearns2001). Moreover, firms with a banker on their board are more likely to engage in short-term borrowing, while firms with an investment banker on the board are more likely to issue bonds (Stearns and Mizruchi Reference Stearns and Mizruchi1993). Firms with bank ties also gain access to what Useem has called “business scan”: they have an unparalleled view of the economy, because banks have privileged access to information about firms, are invited to sit on boards, and are better at recruiting directors from heavily interlocked firms to sit on their own boards (Useem Reference Useem1984; Mintz and Schwartz Reference Mintz and Schwartz1985; Davis and Mizruchi Reference Davis and Mizruchi1999).

Bank prominence thus favors governance and political cohesion among a corporate elite (Davis and Mizruchi Reference Davis and Mizruchi1999). In the United States, for example, firms in economically interdependent industries, and particularly those connected through the same banks, contribute to similar political candidates (Mizruchi Reference Mizruchi1992). Thus, banks not only provide access to information and monitoring but also, in their role as gatekeepers to short-term finance, structure political action in a way that other types of ties do not. Bank prominence also supports other functions: in the case of Japanese keiretsu, the system of banks with extensive investment in industry (and industry with extensive cross-ownership of shares) existed not only to organize relationships among firms, their shareholders, and senior managers but also “to facilitate productive efficiency.” Thus, banks existed not only to resolve the Berle and Means problem of monitoring – and hence address the central problem of corporate governance – but also to implement what they call “contractual governance”: monitoring suppliers or customers for cooperation when it would be impossible or impractical to write contracts (Gilson and Roe Reference Gilson and Roe1993). Finally, in the context of business groups, when banks are in control they act much as an internal financial market, transferring assets toward better investment opportunities when compared with industrial groups (Perotti and Gelfer Reference Perotti and Gelfer2001).

Broad business groups

Contractual governance is a core characteristic of cross-ownership and generates large advantages in creating coalitions by facilitating monitoring and bargaining. Such cross-ownership among nonfinancial firms helps to reduce opportunism in long-term relationships and maintains internal discipline and monitoring among managers due to the ability of coalitions to threaten managers with removal from control (Berglof and Perotti Reference Berglof and Perotti1994). Cross-ownership networks thus can lead to the development of reputational mechanisms over time as firms exert their voice, monitor each other, and join together to exert influence. The diversification that results from cross-ownership means that institutional actors have many points of contact (the firms in which they have stakes), raising the value of reputation. In turn, this creates economies of scale in monitoring (Black Reference Black1992). Such business groups are also a substitute for missing or inefficient markets (for example, financial markets) and thus serve to facilitate the sourcing of finance (Leff Reference Leff1978, cited by Almeida and Wolfenzon Reference Almeida and Wolfenzon2006; Khanna and Palepu Reference Khanna and Palepu1997; Khanna and Palepu Reference Khanna and Palepu1999; Khanna Reference Khanna2000; Ghatak and Kali Reference Ghatak and Kali2001; Kim Reference Kim2004).

Gilson and Roe (Reference Gilson and Roe1993: 874) understand such groups as solutions to long-term production problems that would otherwise require a complex series of contracts among a number of parties. This same logic extends to the complex political problems that accompany production. In other words, I consider institutional bargains among interests as much a part of the production problem as the long-term relationships among suppliers, creditors, and customers who require just-in-time delivery, quality standards, joint investment in procedures and new products, and the costly tailoring and specialization needed to create complex products. Firms are trying to solve a series of institutional problems in order to make and/or raise profits: they require institutions tailored to their interests, labor laws that make their work possible, product standards of a certain form and stringency, public contracting laws, subsidies, tariffs, and a host of other institutional goods. Thus, contractual governance is the business equivalent of collective action – with cross-ownership being the commitment mechanism that reduces the risk of opportunistic behavior among allies. The parallel can be extended, and is reinforced by the fact that pacts of political action among firms cannot be formalized in the way that contracts can be written to mitigate risk among suppliers and customers.2

Moreover, just as long-term relationships between two hierarchically integrated firms are fraught with risk for both purchaser and supplier, so is the decision to undertake coordinated political action. In both cases, firms must make commitments that are difficult to reverse and that leave them vulnerable to exploitation. Just as large investments tailored to a particular customer limit firms’ flexibility, so firms burn their bridges when allying with a particular political party in order to achieve their goals. Similar to the Japanese keiretsu, in politically allied firms, cross-ownership provides a credible commitment mechanism in high-risk situations. Diversified ownership also leads firms to focus on structure and process rather than firm-specific concerns (Black Reference Black1992). Thus, when cross-ownership and diversified ownership are present, firms will tend to focus on broad procedural and structural issues rather than the concerns of any one specific firm or sector.

Institutional investors

The hallmarks of the so-called fiduciary capitalism brought about by the dominance of institutional investors are dispersed ownership and long time horizons (Hawley and Williams Reference Hawley and Williams1997). The term “fiduciary” alludes to the duty of institutions to act in the interest of their beneficiary. When legal provisions and norms may not be so well developed and market integrity is low (Pistor, Raiser, and Gelfer Reference Pistor, Raiser and Gelfer2000), as in the post-socialist world, the presence of institutional investors implies wide stakeholdings and longer time horizons. In the United States, fiduciary duty has unexpectedly reinforced the link between ownership and control by engaging funds in the management of firms (Hawley and Williams Reference Hawley and Williams1997). As a result, institutional investors provide a horizontal link between corporations and function as powerful collective actors usually representing a diverse array of firms. Hence, they perform many of the same functions as banks.

Hierarchical

Family firms and individually owned industrial groups or pyramids are two hierarchical forms of ownership that lower the likelihood of collective action.

Family firms and industrial pyramids

Family or individually controlled firms, which have become common and visible players in the post-socialist environment, are characterized by the dominance of control over ownership. Such firms thus have different configurations of agency, with the key features of family dominance over other shareholders and the capture of professional management by the family (Morck and Yeung Reference Morck and Yeung2003). It has been argued that family firms experience better governance because they have concentrated ownership and thus more focused decision making (Jensen and Meckling Reference Jensen and Meckling1976 and Shleifer and Vishny Reference Shleifer and Vishny1997, both cited by Morck and Yeung Reference Morck and Yeung2003). As Morck and Yeung point out, however, it is important to distinguish between different types of family firms. Those in which family control is highly concentrated or absolute naturally have very low agency problems, because ownership and control rest with the same individuals (barring intrafamily conflicts, which are beyond the current focus). In firms in which a pyramidal structure is used, the family owns a group of firms, and outside investors are brought in to provide capital but are never allowed to acquire a majority of votes in these firms. In terms of corporate governance, the resulting agency problem emerges because managers serve the interest of the family while neglecting other shareholders (Morck and Yeung Reference Morck and Yeung2003). Moreover, because of the pyramid structure, the family firm bears a decreasing share of the costs and risks in firms lower in the pyramid.3 As a result, the family can retain a controlling stake in a large number of firms, benefiting from the capital of public shareholders while bearing increasingly small shares of the risk as the pyramid grows.

What are the interests of such groups? One argument, akin to an incumbency argument, is that family firms have an incentive to prevent innovative upstarts from eroding the value of “old money.” In other words, it is in the direct interest of established firms to prevent the emergence of new competition (Morck and Yeung Reference Morck and Yeung2004). Supporting this view, Rajan and Zingales (Reference Rajan and Zingales2003) have shown how the wealthy elite, having used existing financial institutions to become wealthy, redesign those same institutions to lock in their position and protect their profits. Therefore, as pyramids become more extensive, their interest in subverting and their ability to subvert economic institutions to their own purposes grows, and they gather clout in what are effectively a series of predetermined majoritarian contests to control capital, and thus influence. As a result of this influence, old families do extremely well in political lobbying because of lobbying’s dependence on networks and money (Morck, Strangeland, and Yeung Reference Morck, Strangeland, Yeung and Morck2000; Rajan and Zingales Reference Rajan and Zingales2003; Morck and Yeung Reference Morck and Yeung2004). On the basis of this ability, old families erect barriers to discourage competition and subvert institutions. Thus, family firms correlate with more interventionist governments, less developed financial markets, more onerous bureaucratic obstacles, price controls, and a lack of shareholder rights protection (Fogel Reference Fogel2006). In other words, economies with a significant presence of family firms are likely to have institutions that discourage new entrants and protect family business interests. Family firms thus protect their own profits while functioning in market environments that are not efficient. Their success and emphasis on self-preservation seriously decrease the likelihood of coalitions, and, even when brief coalitions among family firms may emerge, these are likely to seek to halt institutional development.

Arguments applying to family pyramids can also be extended to industrial pyramids – groupings of firms owned by a parent industrial firm with a few shareholders. The difference in political behavior will depend on the extent to which industrial pyramids are the result of vertical integration into a supply chain, and unite firms in closely related sectors.

Firm collective action

As the previous sections show, firms that tend to promote a more horizontal structure raise the likelihood of collective action by facilitating information flow, monitoring, and credible commitments. Firms that promote hierarchical structures are better placed to defend the status quo and narrow elite interests, and thus they lower the likelihood of broad collective action.

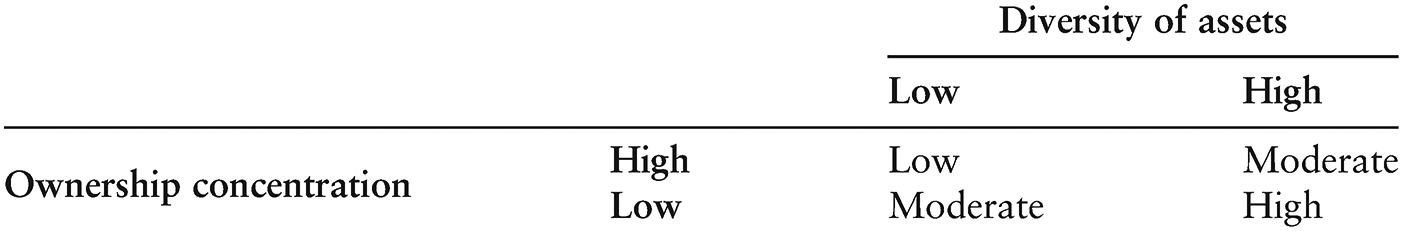

Having introduced these different incentives for different types of firms, it is possible to construct a framework for business political action in terms of the factors that shape the extent of firm cooperation. Two key features governing the emergence of coordinated political action are (1) agency problems (if owners and managers are the same person, their interests overlap; if owners and managers are different people, agency conflicts are likely) and (2) the diversity of assets, which reflects the breadth of ownership networks.

What are the expected outcomes as these two features vary? High asset diversity, meaning that firms across different sectors of the economy have links through common owners, raises the likelihood of coordination, because common ownership interests trump asset-specific interests. This is the case because common ownership of firms in different sectors will tilt collective action toward non-sector-specific preferences, rather than industry-specific demands. As a result, firms will be likely to find joint ground on which to broadly coordinate their political demands. High levels of the agency problem (found under concentrated ownership) instead lower the likelihood of firms coordinating their political demands, because high levels of this problem allow controlling owners to separate minority shareholders from control of their investments, making credible commitments to broad coalitions difficult. This relationship is summarized in Table 2.3.

Table 2.3 Agency problems, asset diversity, and the likelihood of collective action

Why does concentrated ownership lower and dispersed ownership raise the likelihood of collective action? Concentrated ownership is a sign of low levels of underlying social trust and increases the influence of a small and established elite that seeks to sustain the status quo. This elite also faces incentives to exercise political pressure in order to sustain the status quo. According to Morck and Yeung (Reference Morck and Yeung2004: 392), close ties “between members of a small elite magnif[y] the returns to political rent seeking by this elite.” Investors hold concentrated shares only in order to exercise control and gain a strategic input into the management of the firm (this block need not be a majority stake, because small shareholders often do not vote). If investors are not concerned with control, according to portfolio theory, passive portfolios should be diversified across industries and countries to reduce risk.

Owners are often concerned with control when they are faced with conditions in which passivity equates with risk. In other words, the ownership structure is in some ways a reflection of the extent to which there is social trust and elites expect to be able to cooperate. Dispersed ownership is possible in contexts in which the expectation is high, while concentrated ownership exists when common ventures among strangers cannot easily be sustained.

One example of concentrated ownership – family firms – illustrates how it undermines collective action. Concentrated ownership in family firms lowers the likelihood of collective action because, in order to maintain their competitive edge and prevent the erosion of their wealth, they operate in ways that are less socially responsible than nonfamily firms (Chrisman, Steier, and Chua Reference Chrisman, Steier and Chua2006). The owners of old wealth and corporate assets are the most likely funders of innovation, but they prefer to withhold investments in anything that threatens the status quo. In fact, economies with more family-owned assets spend less on research and development (R&D) and file fewer patents. Family firms also spend less on R&D than comparable nonfamily-owned firms (Morck and Yeung Reference Morck and Yeung2004). Concentrated ownership supports cooperation between a narrow elite of managers, capital and/or oligarchic families, and political elites who are likely to support the status quo or their own narrow interests at the expense of the broader political economy (Morck and Yeung Reference Morck and Yeung2004). In fact, higher levels of family control are associated with inferior quality in terms of bureaucracy, higher barriers to entry (making the entry of innovators more difficult), and more extensive regulatory burdens (Fogel Reference Fogel2006). Although it is possible that family firms are just more adept at dealing with such obstacles and do not push for institutional reforms, it seems more likely, based on agency theory and incumbency, that these firms are using their power to affect government policy and block competition (Fogel Reference Fogel2006). For example, financial markets in economies dominated by family firms are likely to be intentionally less advanced because corporate elites favor a weakened financial system to maintain the position of already powerful firms (Rajan and Zingales Reference Rajan and Zingales2003). Further, when ownership is concentrated, politicians tend to emerge from families that control the largest firms in an attempt to reinforce economic power with political power (Faccio Reference Faccio2006). Concentrated ownership thus bolsters the influence of a small and established elite seeking to reinforce its status through both the economic and political arenas.

In contrast, Morck and Yeung argue that dispersed ownership is related to a broad and dispersed elite. Dispersed elites have incentives to put their capital to the best use possible and seek the highest returns available by investing in innovative practices. Countries with this structure sustain high rates of growth because assets are used in a more efficient manner and are directed toward innovation (Morck and Yeung Reference Morck and Yeung2004). Because dispersed owners obtain economic benefits from innovation instead of by exercising pressure to obtain rents, defending the status quo, and creating barriers for new entrants in the marketplace, they are more likely to support political projects that improve market-supporting institutions.

These observations support the view that, when agency problems are high or asset diversity is low, firms will tend toward industry-specific demands but have a difficult time pursuing them because of the small space within which they are able to define goals. This dynamic may be reversed at the highest levels of ownership concentration, however. It is possible, if the principal shareholders are sufficiently large and sufficiently few in number, that they may be able to coordinate despite the presence of agency problems and regardless of the level of asset diversity. In other words, ownership concentration in such cases may trump asset diversity. Apart from these extremes, however, higher asset diversity and lower levels of the agency problem (i.e. lower ownership concentration) will raise the likelihood of coordination among firms.

The next section applies these arguments to empirical data. Scholarship that attempts to understand how economic structure affects politics has focused on ownership concentration (mean shareholder size) or the role of banks in ownership (because banks tend to hold smaller shares on average). Below, I use these two types of data as proxies for the level of agency problems (through ownership concentration) and the level of asset diversity (by considering the role of financial firms and public ownership, because both are more likely than other types of investors to spread their investments across sectors in order to mitigate risk).

Firms in central and eastern Europe

The remaining sections focus on patterns of business collective action in post-communist Europe. The argument thus far has been that the structure of networks between firms, which depends on the size of the average shareholder (ownership concentration) and the extent to which common owners link different sectors, shapes the window of opportunity for business to act collectively. In the next two sections I present two kinds of evidence. First, I use comparative data for Bulgaria, Romania, and Poland to show that decreasing ownership concentration and rising asset diversity are associated with an increase in business collective action. Second, I conduct case studies of business organizations in these countries to show how collective action organizations developed in Poland around broad and diverse coalitions of businesses. By contrast, Romanian organizations tended to be personal political vehicles. In Bulgaria, organizations were largely irrelevant and unable to organize business as a group.

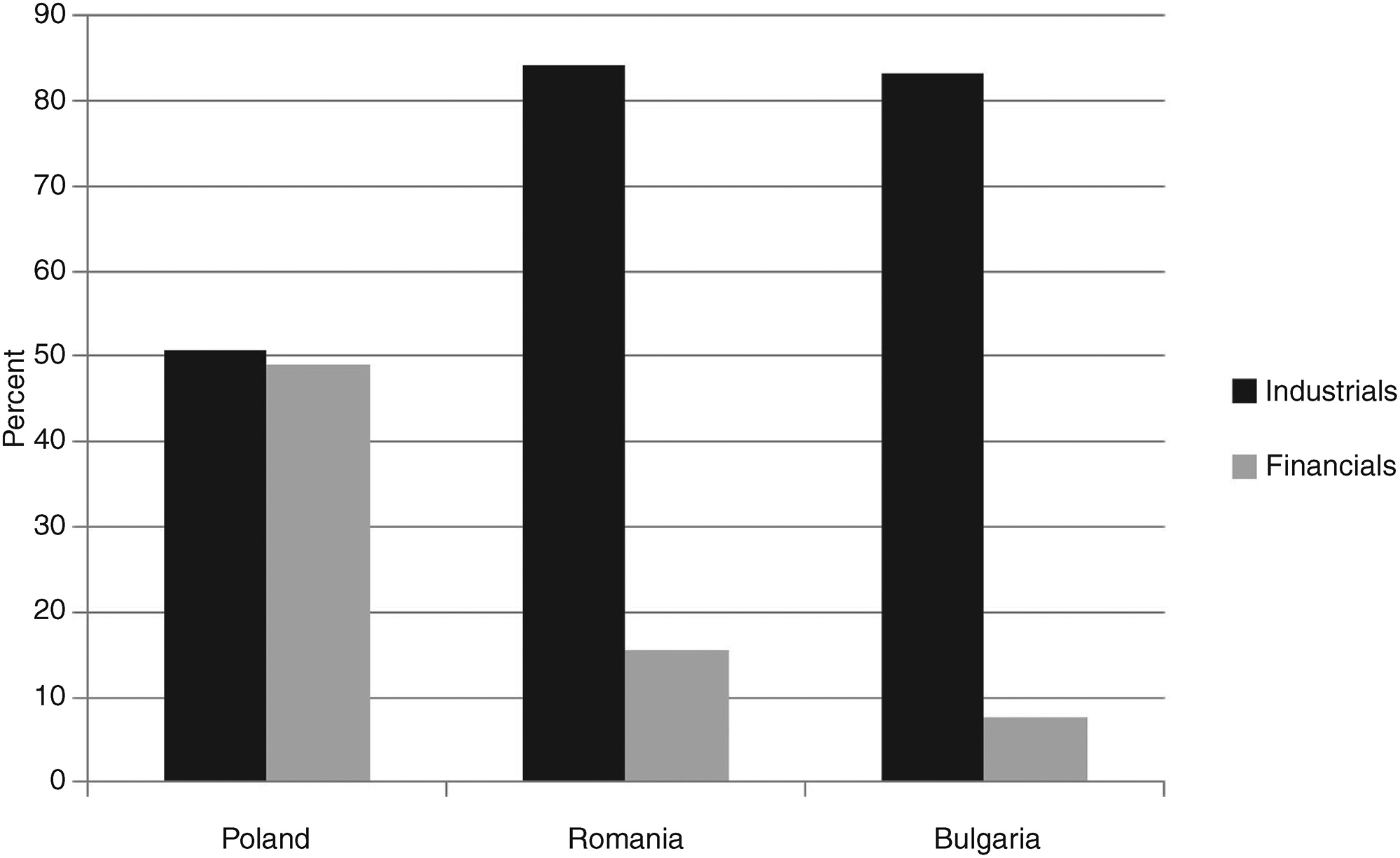

Figure 2.2 compares the role of financial firms in Bulgaria, Romania, and Poland in 2005. The level of ownership by financial firms varies even across the more advanced economies; for example, banks are much less present as owners in Hungary than in Poland. This situation developed because banks and industrial firms were promoted into different roles by the policies of privatization pursued in each country. Thus, the absence of banks in Bulgaria and Romania is not the result of poor economic development or financial failures so much as the product of a conscious policy of promoting industrial firms as owners. In Poland, banks came to be owners of other firms not because they were flush with cash but because the state pursued a strategy of swapping debt for the equity of indebted firms and concentrating the debt in banks while recapitalizing firms. The banks were later partly, and then fully, privatized. This was a very different strategy from that pursued even by Poland’s neighbors. In the Czech Republic, for example, firms were privatized via a voucher system, which only later generated a concentration of ownership as shares came to be publicly traded and gradually landed in the hands of larger owners.

Figure 2.2 Bank and industrial ownership across east central Europe, 2005

Note: All shares over 5 percent.

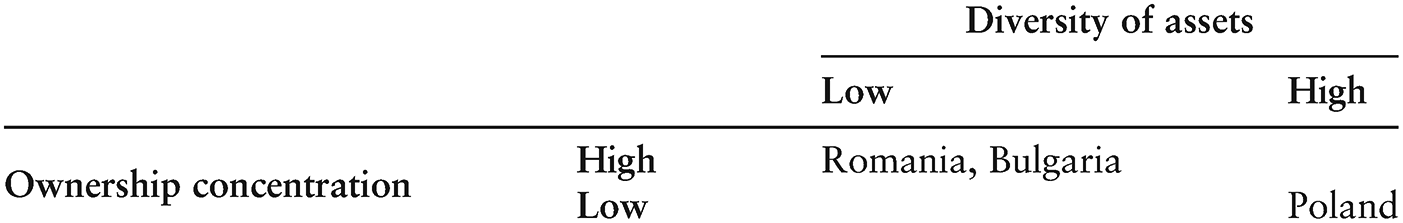

Table 2.4 shows the level of ownership concentration and asset diversity (from Table 2.1 and Figure 2.2, respectively) plotted against each other. To remind the reader, higher levels of ownership concentration are expected to reduce business collective action. Asset diversity is expected to have a positive effect on business collective action because, when the owners are financial firms, they are likely to also own other, dissimilar assets.

Table 2.4 Ownership concentration and asset diversity

In fact, Poland has high levels of asset diversity and low levels of ownership concentration. Romania and Bulgaria, by contrast, have high levels of ownership concentration and low asset diversity. The effect of these two factors leads to sparse networks for Romania and Bulgaria and broad networks for Poland. While Romania and Bulgaria share sparse networks, their institutional development differs as a result of differing levels of uncertainty, as will be examined in Part III of this book.

Business collective action

How do these features affect the emergence of collective action among firms in practice? There are numerous challenges to assessing firm collective action in emerging markets. First, official organizations are often status organizations with little impact. In post-communist countries, many firms continued to be members of such organizations simply because they had always been members. Secondly, much firm collective action takes place informally. For example, numerous informal business councils were created in Bulgaria for the purpose of coordinating lobbying and business alliances. There are, however, ways to try to understand the extent of business collective action using survey data on firms. One available avenue is to examine perceptions of owners and chief executives regarding the extent to which collective firm associations matter and are able to impact politics. Firm CEOs are at the front line of interactions with the state and are consequently one of the best sources of information about practices prevalent among firms.

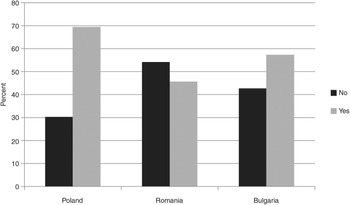

I begin with membership in business associations – a poor indicator on its own, because firms can be members of such organizations for the purpose of status, in order to have access to information, or simply because the marginal cost of membership does not justify withdrawal. Nevertheless, Figure 2.3 shows that at least 40 percent of all medium- and large-sized firms are members of such organizations. On the basis of this evidence alone, we can conclude that a significant number of firms pay membership dues in the belief that membership might help and probably does not carry any negative consequences. As expected, membership is highest in Poland, where more than twice as many firms are members as are not members. In Romania, the majority of firms are not members, while slightly more Bulgarian firms are members than not. This is in line with the outcomes expected as a result of ownership concentration and the diversity of assets.

Figure 2.3 Membership of business organizations

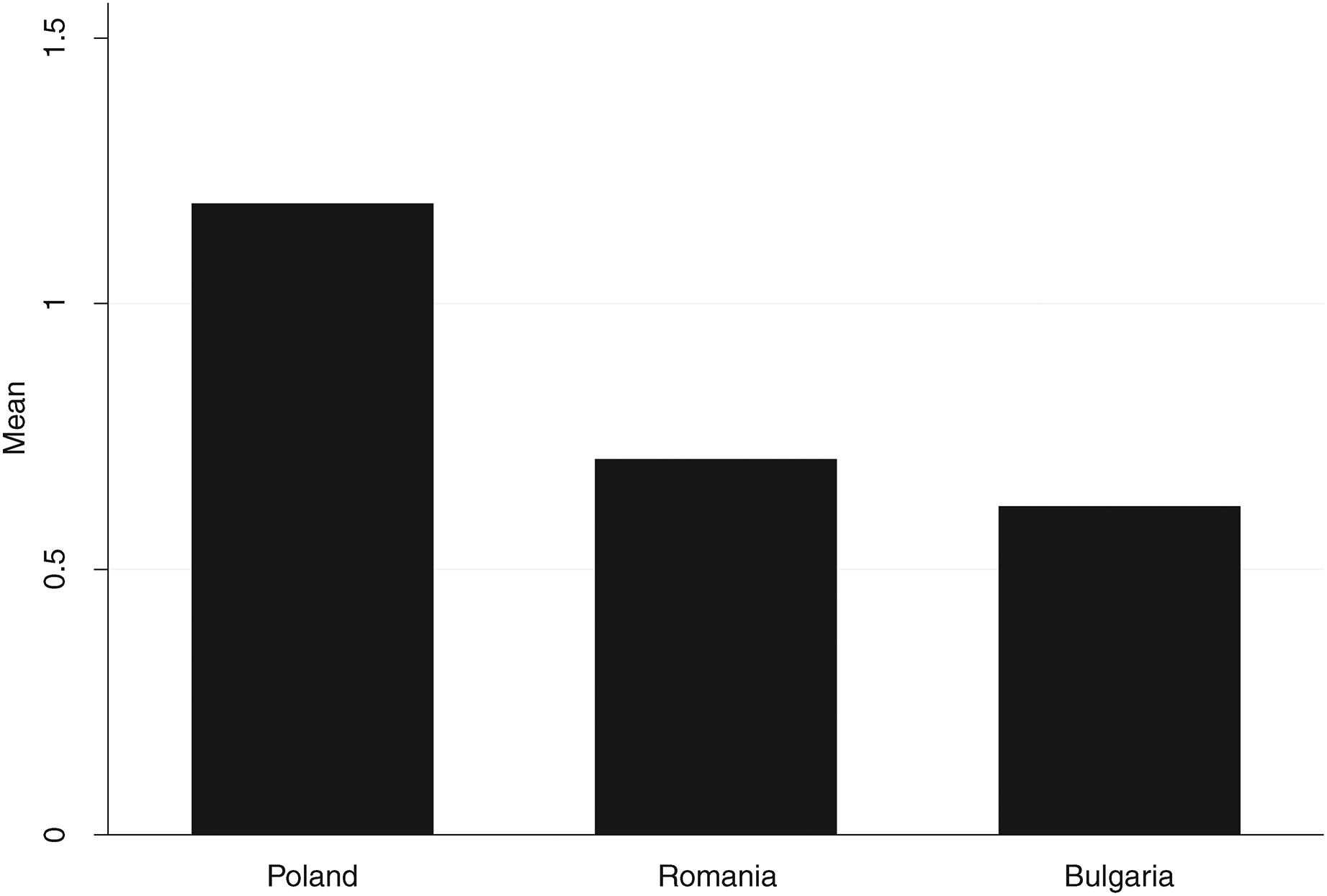

BEEPS (EBRD 2005b) makes it possible to also assess firms’ views of the value of business association or chamber of commerce membership and the impact that firms can have as a group, which is the outcome of interest here. Figure 2.4 shows how medium- and large-sized firms assess the value of business associations in resolving disputes with other firms, workers, and officials.

Figure 2.4 Perceived value of business associations in resolving disputes with other firms, workers, and officials

Note: Means of ordinal scale responses, higher values indicating greater impact.

As expected, associations are seen to have the greatest relevance in the country with low ownership concentration and high asset diversity: Poland. They have the least impact in Bulgaria, the country with the lowest level of asset diversity. The level of influence is also significantly lower in Romania than in Poland. Further, because only a minority of Romanian firms are members of associations, a much narrower grouping answered this question than in either of the other two countries. Thus, Polish associations are much more likely to promote cooperation among firms than associations in either of the other two countries. According to the same question on the EBRD survey (EBRD 2005b), this holds for the role of such associations in performing other functions, such as distributing information about regulations: Polish firms find the most value, while Bulgarian firms detect the least value.

BEEPS (EBRD 2005b) asks a further question about the value of associations in lobbying. Polish firms find such associations less valuable when it comes to direct lobbying than do Bulgarian firms (see Figure 2.5). This result is also consistent with the argument, as it reflects the perception that associations do not serve the direct interests of firms. Further, because so many Polish firms are members of business associations (see Figure 2.3), when associations lobby they do so on behalf of a broad group. The opposite is true for Bulgarian firms. While they generally see little value in such associations along dimensions that foster group collective action, Bulgarian firms find them more valuable for lobbying. This lobbying takes place on behalf of a narrower set of firms, however. As we shall see in the case study of Bulgarian business associations, this is to be expected in a country where narrow groupings of elite firms have created their own powerful associations to pursue specific goals. In Romania, few firms are members, and they receive relatively little in the way of representation.

Figure 2.5 Value of business associations in lobbying government

Note: Means of ordinal scale responses, higher values indicating greater impact.

Institutional factors

Any discussion of collective action needs to also address the institutional context and how it may promote collective action. Do the countries that achieve high levels of business collective action benefit from institutional structures that promote it? Some institutions designed precisely to represent business as a collective actor are present in central eastern Europe and the Balkans. The foremost examples across the post-communist area are collective bargaining arrangements, which bring together employers and employees.

Building on legacies of worker representation in socialist factories, tripartite arrangements linking employers, unions, and the state were developed in most post-communist countries. These were seen as a way to emulate western European arrangements and thus to establish what was understood to be an institutional precondition for acceptance into the community of European welfare states. Although worker–employer negotiations were commonplace, countries varied in the extent to which these negotiations were formalized. For example, in Poland, the law establishing the tripartite commission was passed in Reference Ikstens, Smilov and Walecki2001.

Despite their widespread presence, the general consensus is that such institutions have little impact. With the exception of Slovenia, where collective bargaining covers over 90 percent of all employees, institutional arrangements linking unions, the state, and employers have declined in importance over time and do not cover enough firms to make collective bargaining a meaningful forum within which business interests are brought to bear on government. Crowley (Reference Crowley2004) surveys east European countries and finds that only 44 percent of employees on average are covered by such agreements (this drops to 33 percent if the outlier, Slovenia, is excluded). The form that these arrangements take further reduces the credibility of joint employer–state–union action. Across the region, employer–worker negotiations often do not take place in a centralized fashion, even when they cover a significant number of workers. For example, in Hungary a relatively low coverage of 51 percent is rendered even less meaningful because 80 percent of such agreements are made at the individual firm level instead of the sectoral or central level (Crowley Reference Crowley2004).

Thus, tripartite arrangements are unlikely to serve as a platform on which business collective action can develop. Moreover, with the exception of Slovenia, there is scant evidence that variation in collective action outcomes is determined by the extent of corporatist arrangements in the post-communist context. In that country, high levels of collective action are probably the result of formal tripartite structures. Enthusiasm about the importance of such arrangements in other countries that emerged in the early 1990s has since faded. In the majority of cases, corporatist institutions in post-communist countries have been characterized as weak (Rutland Reference Rutland1993; Ost Reference Ost2000; Crowley Reference Crowley2004), and essentially a “political shell for a neo-liberal economic strategy” (Pollert Reference Pollert1999, quoted by Crowley Reference Crowley2004: 409).

Another approach to exploring firms’ collective action would be to relate it to privatization strategy. Yet the loose relationship between early privatization outcomes and subsequent ownership structures is itself a testament to the fact that post-communist trajectories create legacies, but that these legacies do not prevent countries from changing the path on which they initially embarked. Said another way, the development of ownership subsequent to and often independent of privatization outcomes is a sign that these countries have entered a phase of post-post-communist development. Hence, in order to understand the forms of capitalism that are developing there, we must look well beyond the initial trajectories of privatization. Take, for example, the case of the Czech Republic, where voucher privatization was used to distribute shares of state-owned enterprises to the public. Within a few years these shares had moved their way into concentrated holdings, with the result that the Czech Republic has ened up with the highest average shareholder size in the region. This is not to say that the legacies of early privatization and related policies do not continue to affect ownership structure. The widespread use of debt-for-equity swaps in Poland, for example, made banks into important shareholders. Subsequent exchanges of shares in all countries altered the initial paths, however, in ways that were often discontinuous with the policy choices of the early 1990s.

Three cases: Poland, Romania, and Bulgaria

The remainder of this chapter focuses on a discussion of the role of business associations and gives qualitative confirmation of the patterns seen in the data above. It also establishes a link between the preceding analysis and the following chapters, which focus on detailed within-country data, process tracing, and interview-based research conducted in Poland, Romania, and Bulgaria. The subsequent pages show how the organizational sphere that represents business developed differently in each country on the basis of the characteristics of the prominent actors. This discussion seeks to highlight the characteristics of the organizational landscape in each country, not to explain why the countries followed such different paths, beyond the brief discussion that may be useful to the reader here.

In Poland, the variety of firms that were bound together by common interests led to the development of broad organizations that were consequently able to assemble significant lobbying power. By contrast, in Romania, firm owners joined organizations that were led by business leaders who already had political power. These organizations were largely personal vehicles for their founders and reflected a tendency toward the formation of narrow clique groups. They were able to extract benefits and exert influence, but this ability depended heavily on the personalities of group leaders and their ties to state actors and political parties. Finally, in Bulgaria, the tendency toward self-interest undermined projects of building collective organizations and left a barren associational landscape.

Each of the major Polish business organizations united firms across sectors. Common owners also often joined firms across sectors. Ownership stakes tended to be lower than in other countries, reflecting a tendency among firms to take stakes in other firms. This was reinforced by the prominence of financial firms in the economy, which acquired stakes across sectors because of the common strategy of swapping debt for equity and concentrating this equity in what were initially state-owned banks that were then partly privatized. As a result, the organizations that became powerful in post-socialist Poland were broad rather than sectoral.

The major Polish organizations included the following.

The Polish Business Roundtable (Polska Rada Biznesu: PRB), an elite grouping of the owners and CEOs of the most prosperous private and foreign firms present in Poland, created in 1992. Its presidents have been the owners and CEOs of the largest Polish firms. It was formed to represent business interests and sits on the tripartite commission. Headquartered in a lavish villa in central Warsaw, it also acts as a social club for those holding vast wealth.

The Polish Confederation of Private Employers Leviathan (Polskiej Konfederacji Pracodawców Prywatnych Lewiatan: PKPP), an organization of private employers that was established in 1998 to represent the interest of the private economy. Henryka Bochniarz, a strongly pro-market figure who served as minister of industry in the government of Jan Bielecki, has led the PKPP. In Reference Ikstens, Smilov and Walecki2001 it joined the newly formed tripartite commission. It is also the only Polish member of BUSINESSEUROPE, the main business association at the EU level.

Employers of Poland (Pracodawcy Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej: Pracodawcy RP; before 2010 the Konfederacja Pracodawcow Polskich: KPP), an association, created in 1989, that represents mostly state-owned firms and was seen by members of Leviathan as an organization that emerged from the planned economy and exists to protect the state sector. The Pracodawcy RP is also represented on the tripartite commission. It is led by Andrzej Malinowski, a peasant party activist before 1989 and MP for the Polish Peasant Party (PSL).

The Business Centre Club, which represented the interests of a much larger number of medium-sized firms, as well as some large firms. It was established in 1991. It was created and led by Marek Goliszewksi, a journalist before 1989 and one of the early initiators of the negotiations that led to the roundtable talks.

Although these organizations are broad and diverse, cleavages still exist between groups. They developed around the principle cleavages in the early post-socialist economy: the emergent division between state and private industry, as well as an early division between managers of state-owned enterprises and private entrepreneurs. In other words, organizations tended to unite firms around a broader political struggle. Exceptions to the rule existed, but Polish business organizations tended to have their own political identities related to the post-communist/anti-communist cleavage.

By contrast, the Romanian business organization scene is much less developed. The role of business interest groups and associations in Romania is insignificant. By their own admission, business associations find it very difficult to even collect dues from members, not because member firms lack funds but because they simply do not see the value of group representation. Hence, it is nearly impossible to convince members that it is important for the business community to lobby the state in unison, even for issues on which there is no conflict of interest between firms. According to directors of all influential business organizations, wealthy firms refuse to contribute funds to joint lobbying campaigns or to fund political campaigns by the associations. The leader of one organization lamented the failure of multiple attempts to organize, commenting to me that “there were several attempts to form a consolidated group of firms but they failed.”

A critical question is whether this is in response to a perception that such a business organization cannot be effective because of Romania’s political structure. Or do firms simply prefer direct exchanges? When probed, the directors of the business organizations all attribute the situation to the preference of business to engage in direct exchanges of campaign funds for personal political goods. In an interview, the head of one organization attributed the difficulty of collectively organizing firms to the outlook of firm owners: “Owners don’t have the right formation to address their problems collectively and continue to use methods from before 1989; in other words, they work through political channels to address their problems. These owners have relationships directly with political parties, not through associations.”

The business organizations that do exist in Romania are symbols of failed attempts to build effective representative organizations. They are often “prestige groups,” or personal showcases for single entrepreneurs who are trying to further their political careers. Their other members are firms that would like to benefit from group representation but have not succeeded in causing such an organization to emerge.

The main organizations are as follows.

The Businessman’s Association of Romania (Asociatia Oamenilor de Afaceri din Romania: AOAR), which is largely a personal vehicle for a major businessman who allegedly managed Romanian firms and hard currency funds in Cyprus before 1989. Whereas many members are clearly committed to what they see as the only possible future for Romanian business, the organization is largely a status symbol for Dan Voiculescu’s political and business ambitions.

The General Union of Romanian Industrialists (Uniunea Generală a Industriaşilor din România: UGIR), which was largely associated with the Paunescu family and served as a personal status vehicle.

The General Union of Romanian Industrialists 1903 (Uniunea Generală a Industriaşilor din România 1903: UGIR-1903), a rival organization to UGIR that established itself as the legitimate heir to the original organization after a lengthy court battle.

These bodies are very different in character from those present in Poland. Businesspeople such as the Paunescus, who were closely connected to the Romanian Social Democratic Party, did not need formal organizations for any purpose other than the status attached to the organization itself. This status was considerable; a business organization called UGIR had been created in 1903 and operated to represent the interests of pre-war industrialists. This group was of particular interest because the Paunescus and many of their peers had allegedly emerged from Romania’s security apparatus and sought to deflect calls for investigation of their dealings by assuming the outward appearance of conventional businesspeople. For interest representation, however, they opted for a one-to-one strategy by using their links to the PSDR, which held power without interruption until 1996 and regained power in 2000 from an ineffectual opposition coalition. Interviewees thus repeatedly argued that the Paunescus do not need such an organization for lobbying purposes.

The desire for status organizations led to a bizarre conflict, however, over who the rightful heir was to the original UGIR. Multiple groups of businesspeople sought control of the name of a new organization that was to resume the activities of a powerful pre-war organization. The Paunescus and their allies eventually decided on a new name, UGIR-1903, to emphasize their claim as the continuation of the original UGIR. UGIR-1903 became less active after 1996 because the Paunescu family relocated to the United States in order to avoid prosecution once the Romanian democratic opposition came to power.

AOAR had a similar link to Voiculescu, one of the wealthiest new businesspeople of the 1990s. His dealings were the subject of much discussion because of this alleged links to businesses and accounts belonging to the Ceausescu regime abroad. Again, it became a vehicle through which a coalition of businesspeople sought to acquire a legitimate image.

The two organizations that undertook most lobbying on behalf of business, organize executive and entrepreneurial education, and provide a location within which to network were the alternative UGIR and the Romanian Chamber of Commerce (CCIR). These organizations have had very little actual impact on policy, however.

Overall, Romanian organizations formed around and worked to further the interests of particular powerful business groups, and thus they sustained a certain level of cooperation among their members, who probably sought to attach their fortunes to the individuals and firms that anchored each particular organization.

By contrast, the Bulgarian organizational scene was a barren landscape. Three large organizations were divided according to the historical identities of the firms they represent. These were as follows.

The Bulgarian Industrial Association (Българска стопанска камара), which was established in 1980 and retains an organizational structure that recalls socialist industrial organization. It continues to represent industrial “branches” and coordinates the organization of branch associations. Moreover, individuals who rose through the socialist industrial hierarchy staff it and sit on its management board. Since 1990 most of those who retain a management role have served as directors of state-owned enterprises or formed firms that have strong ties to the state sector.

The Bulgarian Industrial Capital Association (Асоциацията на индустриалния капитал в България), which was created in 1996 as a union of privatization funds and brings together high-profile managers from the state sector.

The Bulgarian Investors Business Association (BIBA), which was formed in 1992 to represent the interests of foreign investors in Bulgaria against some of the early attempts to keep foreign direct investment (FDI) at a disadvantage.

These groups have negligible influence, however, and were not able to make progress in formalizing the process of affecting the policy-making process. Describing the general approach to lobbying, even the leader of one association said in an interview, “Foreigners come here and tell us that we should paint in these colors. But we have our own colors. Why should a lobbying law be an important institution for us?” Another business organization leader added, “Business has no interest in investing in the main organizations.” Recounting how the business community was divided, a business owner said, “In Bulgaria, the different organizations that were created could not carry through their vision because each organization was working for its own survival and met with lots of opposition.” Summing up the actual interaction between parties and firms, one politician said simply, “The moral of the story is that they all interact behind the scenes.”

Not surprisingly, several additional, informal groups were formed in Bulgaria, whose members carried somewhat more influence than the above-mentioned organizations. These were the groups that formed around business clusters. The first of these was known as the “Group of Thirteen” (G-13), which emerged as a lobbying vehicle in 1993 and dominated the private sector until 1995 (Synovitz Reference Synovitz1996). This group, including subsidiaries, consisted of the owners of the largest banks, insurance companies, stock exchanges, large trading companies, newspapers, and private security firms. The group was formed with the intention of protecting Bulgaria from the entrance of foreign firms. Member firms aimed to work together in order to obtain preferences, licenses, and other preferential benefits from the state. The group even created its own business organization, the Confederation of Bulgarian Industrialists. Divisions began to appear among the members quite early, however, as individual firms had differing interests. Some of these divisions were driven by the narrow interests of business owners, most of whom focused on various primary activities ranging from telecommunications to banking. Some realized that they could benefit from doing business with foreign firms, while others benefited from protection, which clashed with the stated purpose of the organization. Even the identities of the individual business groups that made up the G-13 was grounds for disagreement beyond single policy areas; this disagreement reflected the inability of firms to elaborate preferences as a group. Thus, as firms tried to diversify their holdings, individuals also came into conflict around privatization deals. The one-to-one manner in which preferences were awarded to firms in such deals meant that the organization could not offset the divisions arising from them. Faced with conflicts, firms fell back on a dyadic logic.

BIBA also accused the group of supporting economically nationalist policies that might have served the interests of domestic private business but were in conflict with those of foreign investors. Those firms interested in joint ventures with foreign firms sought closer ties to BIBA, making the institutional landscape unstable. Finally, the firms of the G-13 began to lose their political protection as economic pressure on Bulgaria mounted.

As the Confederation of Bulgarian Industrialists crumbled and many of its member firms – the early winners of the transformation – failed or faced significant economic difficulties, it was replaced by other groups with new political protectors. These shifts in business coalitions are discussed in more detail in the following chapters. Their significance here is to underline the unstable nature of the organizational landscape in Bulgaria. In contrast to the Romanian organizational landscape, these organizations were undermined by the excessively individualistic nature of negotiation and interest expression. In other words, interests were conceptualized in such an individualistic fashion that they precluded the successful expression of joint aims.

The striking difference between these three countries is that state–business relations were conducted on fundamentally different bases. In Romania, individual leaders were able to form personal organizations that attained a measure of stability, accounting for a higher level of impact among business organizations. In sharp contrast, the Bulgarian business leaders were unable to make any significant progress in creating organizations (with the exception of BIBA, which owes its prominence to support by foreign investors). Instead, individual business owners and CEOs used their influence over political actors to control both the content of policy and individual decisions. Although attempts to form groups were made, they were doomed from the outset, undermined by the strong dyadic alternative available to those seeking influence in politics.

Conclusion

These three cases complement the survey data presented earlier to make the broader point that horizontally networked and heterogeneous groups are more likely to have success in articulating group goals than narrow groups or groups wherein individualistic ties interfere with the elaboration of group objectives. There is a middle range in which narrow groups can be held together by leadership, and the Romanian case is precisely a case of the latter – individuals who exerted enough authority were able to create lasting groups – but these organizations depend on individual personalities for their cohesion, and, although they are stable, their performance is very modest. Poland, by contrast, is a case in which heterogeneity and networks in a period of uncertainty and political conflict raised the incentives for firms to collaborate. Bulgaria represents the other extreme, where the lack of network ties among firms and a strong tendency toward dyadic relations undermined efforts to elaborate group goals.

This chapter has argued that there is a link between ownership structures and the development of firm collective action, drawing on a literature that focuses on the macro-effects of corporate governance. I have shown how broad networks raised the likelihood of collective action. More precisely, two dimensions of networks – (1) the diversity of assets and (2) agency problems in the management of the firm – predict when firms have an incentive and the ability to act collectively. Data on the average size of shareholders and the prominence of firms that tend to hold heterogeneous assets, together with survey data on membership in business organizations and the value that firms obtain from those organizations, illustrated the effect of these two dimensions on business collective action.

1 For example, it is well known that Japanese firms exchange their own shares as a form of credible commitment to joint decisions because of the difficulty of repeatedly writing contracts to govern supplier and customer relations (Gerlach Reference Gerlach1992).

2 It is worth noting that in most cases even business contracts cannot address in a practical manner the universe of possible contingencies in a complex transaction. Instead, mechanisms are devised to allow parties to address actual contingencies as they arise (Williamson Reference Williamson1985).

3 For example, the family owns the family firm outright. In turn, the family firm owns 51 percent of firm A, which owns 51 percent of firm B, which owns 51 percent of firm C. In this example, the family has only an actual 25.5 percent stake in the profits of firm B, and a 12.5 percent stake in the profits (or costs) of firm C. See Morck and Yeung (Reference Morck and Yeung2003) for more detail.