We invest in the US for its rule of law, yet the biggest challenge for us is also its rule of law.

In the late 1970s, China emerged from the shadows of the Cultural Revolution as an autarky steeped in extreme poverty, leaving few Chinese businesses with the means or desire to invest abroad. Fast forward to today and that once impoverished nation has since evolved into the world’s second largest economy.Footnote 1 Chinese companies have channeled billions of dollars into overseas investments,Footnote 2 igniting intense debates across the globe. While some have welcomed this new influx of capital, there is a growing concern among others that these Chinese investors might export unethical business practices, show disregard for local cultures, breach host-state laws, and clandestinely manipulate host-state politics to align with the interests of the Chinese government.Footnote 3 Consequently, an extensive body of literature has emerged that analyzes the impacts of China’s global economic expansion. However, no one has so far explored how Chinese companies maneuver within the sophisticated legal institutions of developed host nations, such as the United States.

Chinese investors obviously face mounting challenges in navigating the US legal system. As will be detailed shortly, corporate management and business transactions in China often relegate the legal system to a more peripheral role. Having thrived in such a home-state environment, Chinese companies encounter formidable institutional obstacles when operating in developed countries with robust, strict, and complex legal systems. Obviously, nowhere else are the hurdles as high as in the United States. How then do Chinese investors negotiate the omnipresent legal risks? Will they persist in treating law as an inconsequential or purely cosmetic aspect of their operations (inertia), adapt to mirror the behavior of US companies (isomorphism), or display mixed responses shaped by both home- and host-state institutions (dualism)? This book sets out to answer these questions by exploring a range of interconnected topics.

This chapter begins with an overview of China’s outbound direct investment, particularly emphasizing Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) in the United States. It then introduces a variety of research questions, ranging from the role of in-house legal counsel in Chinese companies to their legal responses when confronted with unfair treatment by the US government. Next, this chapter selectively summarizes and critically reviews the existing literature pertinent to the interactions between multinational companies (MNCs) and the complex US legal system. Subsequently, it formulates a comprehensive theoretical framework predicated on dual institutional influence, which will be applied consistently throughout the book. The chapter concludes with a description of the research methodology.

1.1 Chinese Direct Investment in the United States

Despite the scrutiny it has received, outbound investment from China is a rather recent phenomenon. In the post-Cultural Revolution decade, the Chinese government strictly limited outward capital flow due to a dire shortage of foreign exchange reserves.Footnote 4 Even after the initial restrictions were loosened,Footnote 5 Chinese outbound FDI remained at a low level of around $1.2 billion.Footnote 6 A series of embezzlement scandals and investment failures subsequently led the State Council to conclude that China was “unprepared for large-scale foreign investment,”Footnote 7 resulting in tighter controls and a 20 percent annual decrease in outward investment proposals from 1992 to 1996.

However, China’s continuous economic growth, fueled in part by increasing inbound investment and a thriving international trade, boosted its foreign exchange reserves. Some government officials started advocating for less restrictive policies and encouraged “competitive” state-owned enterprises (SOEs) to invest abroad.Footnote 8 In 2000, a Politburo meeting developed a “Going Out” strategy to promote China’s outbound FDI, which the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) National Congress promptly endorsed as a strategic national policy for fostering economic development.Footnote 9 Against this backdrop, the central government set up institutions to facilitate investment and ratified dozens of investor-friendly bilateral investment treaties.Footnote 10 The government also streamlined and decentralized reviews for outbound investment proposals and supplied Chinese investors with low-cost capital. For example, state-owned banks created overseas loan programs,Footnote 11 and the State Administration of Foreign Exchange simplified procedures and reduced thresholds for Chinese firms to obtain foreign currencies for overseas investments.Footnote 12 In the early 2010s, as foreign exchange reserves continued to multiply, the Chinese government replaced the investment approval regime with a reporting system.Footnote 13

As the government policies evolved, so too did the characteristics of China’s outbound investment. Due to earlier restrictions and the initial composition of the Chinese economy, state-owned conglomerates had been the dominant players, responsible for 75 percent of the total amount of Chinese outbound investment until 2010.Footnote 14 The majority of these investments were concentrated in a few strategic sectors such as energy and transportation.Footnote 15 In the following decade, however, private Chinese investors from various industries significantly increased their acquisitions of foreign assets and surpassed the SOEs as the primary driving force behind China’s investment outflow.Footnote 16

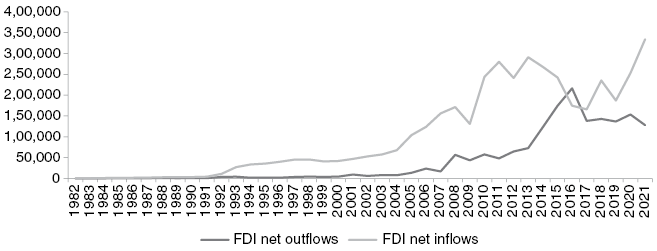

However, the growth of China’s outward FDI reached its peak around 2016 (see Figure 1.1), as the central government, alarmed by a precipitous drop in its foreign exchange reserves and concerned about capital flight, reinstalled certain approval requirements for major outbound investment deals.Footnote 17 Meanwhile, an abrupt deterioration of US–China relations following the election of Donald Trump dimmed the prospects for the Chinese economy and alerted Chinese investors to geopolitical risks and uncertainties associated with overseas investments, causing a sharp drop in China’s outbound FDI.

Figure 1.1 FDI inflows and outflows, China 1982–2021 (millions of US dollars)

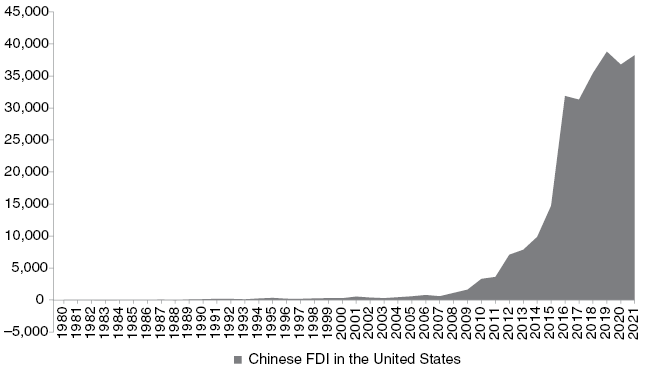

Chinese FDI in the United States follows a similar trajectory (see Figure 1.2). Before the trade war began, the United States had been the largest national recipient of China’s outward investment.Footnote 18 In contrast to those in resource-rich developing countries, Chinese investments in the United States span various sectors, including real estate, automotive, biotech, and entertainment.Footnote 19 Initially, the vast majority of the Chinese investors had embraced long-term business plans and intended to reinvest most or all of their US profits.Footnote 20 However, Trump’s anti-China policies and the ensuing bipartisan consensus on China as the “most consequential strategic threat” aggravated the already challenging legal and regulatory environment for Chinese investors.Footnote 21 New FDI from China dropped significantly, and some investors opted to downsize or even shut down their US operations. Nonetheless, most Chinese investors with substantial US businesses have been reluctant to exit this large, strategically important market.Footnote 22

Figure 1.2 Chinese FDI in the United States 1980–2021 (direct investment position on a historical-cost basis; millions of US dollars)

TikTok’s experience in the United States serves as a fitting example. ByteDance, the Chinese owner of TikTok, was founded in 2012 by a twenty-nine-year-old Chinese entrepreneur with an engineering background. After establishing a successful business model in China, ByteDance entered the US market by acquiring Musical.ly in November 2017 and rebranding it as TikTok, a platform for sharing user-generated shortform videos through multifunctional mobile apps.Footnote 23 Its proprietary algorithm proved highly effective at retaining users, and in March 2023, TikTok reported as many as 150 million monthly active users in the United States.Footnote 24

With US investment comes litigation. Between the acquisition of Musical.ly and December 2020, TikTok was involved in forty-three lawsuits. Initially, the company had minimal interactions with the US legal system, with only one suit filed against TikTok in 2017 and no litigation in 2018. In 2019, just four lawsuits involved TikTok, a negligible number considering its rapidly growing US operations. However, in 2020, the company participated in thirty-eight US lawsuits. TikTok dealt with a wide variety of cases, not uncommon for a company of its size. Of the total forty-three cases, thirty-nine were filed against TikTok, and among the four lawsuits initiated by TikTok, three named the US government as the defendant.Footnote 25 These three high-profile lawsuits warrant detailed analysis, which readers will find in Chapter 6.

The US legal experiences of TikTok are not unique. From Huawei to Bank of China, Chinese companies with operations in the United States increasingly appear in court, often as defendants. But from time to time, Chinese companies take the initiative and “raise the legal weapon” to protect their US interests. However, given the vast institutional differences between China and the United States, the ways in which Chinese companies navigate the US legal system remain an important yet unexplored question.

1.2 Literature on MNCs’ Interactions with the US Legal System

While Chinese companies may not have received as much attention from socio-legal scholars, the broader debate about how MNCs negotiate US legal risks and opportunities has generated several streams of insightful literature. One stream focuses on the idea of American legal exceptionalism. This theme stems from a comparison of the US approach to legal ordering, termed “adversarial legalism,” and the systems found in other economically advanced democracies. The distinct “American way of law,” characterized by “formal legal contestation” and “litigation activism,”Footnote 26 builds on a network of interconnected institutions:

An adversarial, lawyer-driven system of litigation shaped by the right to trial by jury; politically-selected, policy-minded judiciaries; a large, entrepreneurial and creative legal profession, armed with powerful tools of pretrial discovery; and a legal culture still pervaded by the idea that law and courts are or should be instruments for effectively protecting individual rights, improving governance, and controlling the exercise of political and economic power.Footnote 27

To substantiate the notion of American legal exceptionalism, researchers have examined the legal and regulatory experiences of MNCs in the United States.Footnote 28 The empirical findings suggest that MNCs operating in the US market face additional burdens in the form of onerous legal service expenses and considerable opportunity and compliance costs, which, “while difficult to quantify,” are “both salient and troublesome.”Footnote 29 Without denying some benefits of lawyer-dominated contestation in dispute resolution and government regulation,Footnote 30 Kagan and colleagues argue that the US system has “demonstrable, counterproductive consequences,” as it pushes foreign investors “toward a more defensive, legalistic relationship with American regulatory officials, consumers, and employees than with their counterparts in other countries.”Footnote 31 The insightful research, however, focuses only on MNCs headquartered in Japan, Canada, Germany, and other post-industrial nations considered to be US allies,Footnote 32 and includes only a few case studies from each country, raising questions about the generalizability of the findings.Footnote 33

Another branch of literature, primarily developed by international business scholars, examines the “liability of foreignness” that non-US based MNCs bear when navigating the US legal system. A notable empirical study in this area discovered that foreign-headquartered MNCs are sued more often in the United States than their US counterparts.Footnote 34 Once again, the study only considered MNCs from developed countries, likely due to the historical absence of MNCs from developing countries in crossborder investment. Moreover, the existing research has overlooked important topics pertinent to US litigation, such as foreign MNCs’ interactions with US lawyers and their development of internal US legal capacity.

Two additional research streams have indirectly explored foreign-based MNCs within the US legal context. First, scholars have debated potential biases against foreign parties in US courts, with one side contending that foreigners and domestic parties receive equal judicial treatment,Footnote 35 and the other presenting empirical evidence of systematic bias.Footnote 36 Despite these opposing viewpoints, a recent study has found indirect evidence of fair treatment – most Chinese companies with US investments have expressed a positive view of the host-country judiciary.Footnote 37 Second, some legal scholars have studied “forum shopping” by foreign parties seeking access to the US judiciary.Footnote 38 Although much of this research concentrates on individual rightholders attempting to sue foreign firms in US courts,Footnote 39 and the evolution of relevant US jurisprudence and its policy implications,Footnote 40 the literature underscores the agency of transnational litigants (particularly their US lawyers) and the complexity of the US legal institutions, both of which are common themes in the chapters that follow.

In summary, while multiple lines of research have delved into the experiences of MNCs within the US legal system, there remains a conspicuous absence of systematic investigation into how MNCs from developing countries, particularly China, negotiate US legal risks. This book endeavors to address this gap by examining a series of interrelated topics, from the internal legal capacity of Chinese companies in the United States to their preferences and behavior regarding litigation. Besides the literature surveyed in this section, subsequent chapters will leverage insights from research in relevant subject areas. For example, although few scholars have studied the in-house legal capacities of Chinese MNCs – a central theme in Chapter 2 – a sizable body of theoretical and empirical research exists on a closely related topic – the global “in-house counsel movement.”Footnote 41 Chapter 2 will engage with this scholarship. Likewise, while scant research exists on Chinese companies’ litigation in US courts, prior research on trial selection,Footnote 42 dispute resolution,Footnote 43 and other relevant topics provide invaluable analytical building blocks for Chapters 4–6. As will be demonstrated throughout this book, examining Chinese companies’ experiences within the US legal system both contributes to, and benefits from, these diverse bodies of literature. Despite the seemingly eclectic theoretical mix, this book consistently applies a unifying theoretical framework of institutional duality, effectively linking all subsequent topical analyses in the remaining chapters.

1.3 Theoretical Framework of Institutional Duality

This book employs a unified framework of institutional duality to dissect the multifaceted interactions between Chinese companies and the complex, rigorous US legal system. An abundance of research on MNCs has explored the influence of institutional environments on crossborder investments, management, and transactions. Despite its subject matter diversity, this body of research draws its intellectual lineage from two theoretical branches, rational choice institutionalism and sociological institutionalism. As these two strains of neoinstitutionalism have already been extensively reviewed and critiqued, and their overlaps and differences well documented elsewhere,Footnote 44 a succinct overview of each will suffice for the purposes of this book.

Research grounded in rational choice institutionalism implicitly or explicitly portrays human actors as solving optimization problems,Footnote 45 with their choices and preferences constrained by exogenous, behavior-regulating institutions defined variably to suit specific research objectives.Footnote 46 In an analytical review of the literature, Williamson aptly categorizes institutions into four levels, with higher-level institutions “imposing restraints on the level immediately below.”Footnote 47 At the top of this hierarchy are “institutions of embeddedness,” which refers to “norms, customs, mores, and traditions.”Footnote 48 Although leading rational choice scholars acknowledge the significance of high-level informal institutions in shaping individual preferences and behavior,Footnote 49 much of the research in this area is focused on the two levels below – formal institutions safeguarding property rights and governance institutions regulating broadly defined contractual relations – and how these institutions address agency and transaction cost problems.Footnote 50

The collective overlooking of the higher level “institutions of embeddedness” may be attributable to their relative stability.Footnote 51 In much of the research adopting this theoretical perspective, informal institutions like social norms tend to remain static, which justifies their analytical exclusion. However, to explore the topics of this book, informal institutions must be taken into account, as they significantly vary between the world’s two largest economies, and the ensuing institutional tensions and conflicts characterize the transnational organizational environment for Chinese companies operating in the United States.Footnote 52

In contrast, sociological institutionalism places greater emphasis on “institutions of embeddedness” and accentuates the role of institutions as both conferring meaning to human actions and defining their boundaries. Institutions are not merely restrictive; they also engender agency.Footnote 53 Sociological institutionalists, rather than treating “tastes” or “preferences” as exogenous or static,Footnote 54 investigate how institutions enable human actors to “construct” their interests and define the set of choices available for “rational” selection. Moreover, they highlight actions that are spurred by concerns for legitimacy or social appropriateness,Footnote 55 or actions that are simply taken for granted,Footnote 56 rather than deliberative, utility-maximizing calculations. Empirically, sociological institutionalists underscore corporate isomorphism in their organizational fields, as opposed to the behavioral and preferential heterogeneity often predicted by rational choice institutionalists.Footnote 57 Additionally, sociological institutionalism often “over-socialize[s]” human actions, downplaying the role of agency as an exogeneous variable.Footnote 58 Under this framework, MNCs tend to be seen as “institutional dopes blindly following the institutionalized scripts and cues around them.”Footnote 59 However, given the multitude and complexity of “institutional pressures from the metaglobal field, the MNC internally, and the idiosyncratic institutional environment of each particular MNC unit,”Footnote 60 as well as the ample space for agency resulting from myriad institutional voids, ambiguities, tensions, and contradictions,Footnote 61 the analytical approach of sociological institutionalists falls short in explaining MNCs’ preferences and behavior in their transnational field.

Incorporating insights from both theoretical approaches,Footnote 62 I devise a dual institutional framework to examine how Chinese companies operating in the United States engage with key components of the host-state legal system. As transnational entities “exposed to two or more cultures, social structures, or sets of routines, one in the home country, and one or more in the host countries in which they operate,”Footnote 63 MNCs constantly face disparate and sometimes conflicting institutional pressuresFootnote 64 that influence their strategies and preferences.Footnote 65 Likewise, any national subsidiary of an MNC encounters “dual institutional pressures originating from its home and host countries.”Footnote 66 When these institutions diverge significantly, as is the case between China and the United States, “competing institutional forces provide different cognitive knowledge, social norms, and regulative policies, which prescribe diverse role models and scripts” for MNC subsidiaries.Footnote 67 Hence, inquiries into how Chinese companies navigate the US legal system must account for the institutional differences and possibly diverging “isomorphic pulls”Footnote 68 from both the home and the host states.Footnote 69 This dual institutional framework extends the rational choice institutionalist approach by emphasizing the effects of heterogeneous informal institutions and, by underscoring the agency of MNCs and the institutional tensions they face, sets itself apart from sociological institutionalism. Further details of the framework are provided in the sections that follow.Footnote 70

1.3.1 Host-State Institutions of Chinese Companies in the United States

At the risk of stating the obvious, the US institutional contexts in which Chinese companies operate directly modify their managerial behavior and preferences.Footnote 71 First, these Chinese companies, now domiciled in the United States, are obligated to comply with US laws and regulations and subject to the general jurisdiction of US courts. In this environment, Chinese companies may adapt individually to an extent that rational choice scholars deem optimal (where the marginal investment in mitigating US legal risks equals the marginal return) or collectively display what sociological institutionalists term “coercive isomorphism.”Footnote 72 Second, Chinese companies operating in the United States engage continually with local nonstate actors such as customers and suppliers. Steeped in this network of US cultural and normative carriers, these companies are subject to pervasive influence of US “institutions of embeddedness.” US norms and values may alter their behavior either by adjusting the payoffs of their strategies, as rational choice institutionalists suggest, or by reformulating their views on the appropriateness or legitimacy of available strategies, as sociological institutionalists propose. Despite the diverging views regarding the causal mechanism, both theoretical approaches predict conforming behavior – Chinese companies behaving similarly to their local counterparts. In summary, to understand how Chinese companies navigate the US legal system, it is essential to consider their host-state institutional environment and its impact on their preferences and behavior. Although this part of the dual institutional framework might seem trivial, its importance should not be understated.

1.3.2 Home-State Institutions of Chinese Companies in the United States

While it is well documented that MNCs often carry features of their home-state institutions “with them when expanding abroad,”Footnote 73 few studies have explored their impacts on MNCs’ adaptation, or lack thereof, to host-state legal environments. Filling that gap, the dual institutional framework developed here pays special attention to the influence of home-state formal institutions, such as laws and regulations, and informal institutions, such as social and cultural norms governing compliance and litigation.Footnote 74 To simplify, I classify the home-state institutional influence into direct and indirect effects.

Both formal and informal home-state institutions can directly influence Chinese companies operating in the United States.Footnote 75 Certain Chinese laws and regulations apply extraterritorially to Chinese businesses overseas. The long arm of Chinese laws has been extending as a result of China’s growing economy and sprawling worldwide interests,Footnote 76 and, in certain instances, as countermeasures to the extraterritorial application of US laws.Footnote 77 Moreover, most senior executives at Chinese companies in the United States, especially those of state ownership, remain Chinese citizens.Footnote 78 These expatriates, most of whom reasonably anticipate returning to China, are theoretically subject to the jurisdiction of Chinese laws based on their citizenship.

Meanwhile, informal Chinese institutions (i.e., “institutions of embeddedness” such as social norms and cultural values) can also directly affect Chinese companies in the United States.Footnote 79 These institutions,Footnote 80 often regarded as preserving stability amid fluctuations in domestic settings,Footnote 81 exert two distinct influences on transnational actors’ behavior and preferences: cognitive effects and normative effects.Footnote 82 Cognitive components of an informal institution, often taken for granted and “virtually invisible to the actors themselves,”Footnote 83 provide descriptions, theories, schemata, and scripts that “specify cause-and-effect relationships”Footnote 84 and “influence the way a particular phenomenon is categorized and interpreted.”Footnote 85 On the other hand, normative components relate to values and attitudes toward objectives, choices, and actions.Footnote 86 These cognitive and normative influences shape the perspectives, values, and interpretations of top managers at Chinese companies operating in the United States, who are often expatriates and “carriers of institutions,”Footnote 87 as they navigate the US legal landscape.Footnote 88 Confronted with normative and cognitive discrepancies in a heterogenous environment, middle-aged Chinese executives naturally resist significant changes that “threaten individuals’ sense of security, increase the cost of information processing, and disrupt routines.”Footnote 89 Additionally, rapid technological progress since the 2010s has made cross-country socialization more accessible and virtually cost-free, reinforcing the norms and scripts internalized by expatriates before their overseas assignments and influencing their law-related preferences and behaviors in the United States.Footnote 90 In summary, both formal laws and informal norms may directly affect the US operations of Chinese MNCs.

Home-state institutions can also indirectly influence Chinese companies operating in the United States through their headquarters.Footnote 91 As legal entities based in China, the parent companies must, at least in theory, ensure that their overseas operations comply with relevant Chinese laws. For instance, as will be detailed shortly, Chinese regulations governing SOEs mandate timely reporting of material foreign legal risks, which may alter the way state-owned Chinese companies approach US litigation. Moreover, informal home-state institutions may also indirectly affect foreign operations through their headquarters, as the norms and values shape how executives at the helm of a global business empire interact with staff at foreign subsidiaries by interpreting or evaluating the behavior of local managers.

Additionally, MNCs’ internal organizational structures often facilitate the transmission of home-state institutional pressure to foreign affiliates.Footnote 92 To reduce agency problems and transaction costs,Footnote 93 headquarters typically design and disseminate corporate rules and practices to subsidiaries.Footnote 94 Even without deliberate top-down diffusion of corporate routines, rules, and structures, local managers may engage in internal mimetic isomorphism, copying the actions and organizational structures of the headquarters when dealing with unfamiliar complex situations in the host country.Footnote 95 Moreover, the internal organizational dynamics both mediate and reflect the institutional effects, rendering them less deterministic.Footnote 96 Thus, the relationship between a Chinese MNC’s headquarters and its US operations, previously studied under the framework of agency theory or transaction cost theory,Footnote 97 remains an important variable to consider, especially in research about intra-organizational personnel arrangement such as the appointment of in-house legal managers in the United States.Footnote 98

1.3.3 Dual Institutional Influences

The two preceding subsections have succinctly highlighted the dual institutional influence that Chinese companies endure while traversing the US legal environment. The ensuing chapters will empirically explore the manifestation of the influence. Topics include the development of internal legal capacities, the selection of US lawyers and consumption of legal services, and their litigation experiences within US courts. Yet, this book does more than merely presenting a special case of transnational legal pluralism.Footnote 99 It takes a major step further by theorizing and investigating how the dual institutional influence varies across firms and its effects on these companies’ interactions with and impacts on the US legal system.

The starting point of the theoretical construction is an inquiry about institutional difference. As alluded to earlier, when an MNC’s home and host-state institutional contexts align, the force of inertia is likely to dominate,Footnote 100 leading the MNC to organize and manage its foreign affiliate akin to a domestic subsidiary.Footnote 101 The inertia will meet little resistance. Canadian companies, for instance, can probably transpose their management preferences and practices onto their US subsidiaries, which likely dovetail with local expectations. However, when the institutional environments diverge significantly, host-state institutional pressure can disrupt and modify the inertial structures, preferences, and behaviors.Footnote 102 The wider the institutional chasm, the more substantial the hurdles and costs the MNC confronts in adapting to the host-state environment.

Notably, the institutional gaps vary at the firm level, reflecting differences in both formal and informal institutional contexts for Chinese companies operating in the United States. Regarding the formal dual institutional context, Chinese companies differ systematically based on their ownership type. As will be elaborated shortly, state-owned Chinese companies must navigate a unique set of formal rules and regulatory mechanism designed to incentivize their staff toward achieving multiple, fluid, and often ambiguous goals.Footnote 103 This unique, ownership-specific institutional environment can exacerbate agency problems and increase transaction costs significantly as these companies engage with market players and regulatory bodies in the United States.Footnote 104 And the distinct institutional effect may surface in various legal dimensions. For instance, to address enhanced agency and transaction costs, state-owned Chinese investors may lean toward expatriating home-state managers, who are trusted, well acquainted with the home-state institutions, and privy to firm-specific information, to oversee US legal matters. The same institutional influence may also modify the way in which state-owned Chinese companies select US lawyers or litigate US disputes.

In addition to formal institutional disparities, Chinese companies must grapple with variable informal institutional gaps between their home and host states. The variations are determined by numerous factors such as a firm’s embeddedness in the home-state environment, corporate decision-makers’ education, age, and exposure to diverse cultures, and intra-enterprise decision-making dynamics.Footnote 105 Broad disparities in norms and values can result in miscommunication, mistrust, and conflicting beliefs and expectations, which generally give rise to high transaction costs and disputes. The gaps may also impact how Chinese companies navigate the US legal landscape. Those facing significant cultural hurdles in the United States, for instance, may prefer local lawyers with Chinese backgrounds, who can more effectively bridge these gaps. Moreover, companies facing large normative discrepancies may struggle to defuse disputes, consequently becoming more susceptible to US lawsuits.

The manner in which Chinese companies respond to differences in the dual institutional environment, formal as well as informal, also hinges on the equilibrium of the divergent and competing institutional pulls. Specifically, the preferences and behaviors of a Chinese company operating in the United States may vary according to the balance of the institutional pressures – “which side of these institutional pressures (often channeled through organizational linkages with the environments) is more potent and exerts a stronger impact.”Footnote 106 At the same time, the companies, while pulled away from their habitual systems of cognition, internalized norms, routines and actions, may resist or strategically implement nonconforming responses.Footnote 107 These interactions determine not only the manner, velocity and extent of the companies’ host-state adaptation, but also their impacts on the host-state institutional environment. Scholars have long recognized that “multinational practices influence local environment,”Footnote 108 and the extent of the influence depends largely on their relationships with the constituents of the organizational field, such as suppliers, customers, and US regulatory agencies.Footnote 109 If the companies have more leverage over these local actors, part of the host-state institutional pressure may be diminished or offset.Footnote 110 Otherwise, we shall observe adaptation and assimilation,Footnote 111 with the host-state institutional influence eclipsing that of the company’s home state.Footnote 112

To illustrate the point, consider the impacts of Western MNCs on Chinese institutions. Up until quite recently, foreign-invested firms in China wielded considerable leverage over their local suppliers, customers, and even regulators.Footnote 113 Consequently, investors from the United States and other developed countries, while adjusting to the Chinese environment in myriad ways, managed to maintain many of their home-state practices, and by doing so significantly transformed their organizational fields in China. For instance, recent empirical research suggests that Chinese regions with concentrated direct investments from the United States and Europe developed better courts.Footnote 114 In stark contrast, the remainder of this book will show that Chinese MNCs, typically lacking leverage over key US market and state actors, have made no more than marginal impacts on the host-state legal institutions.

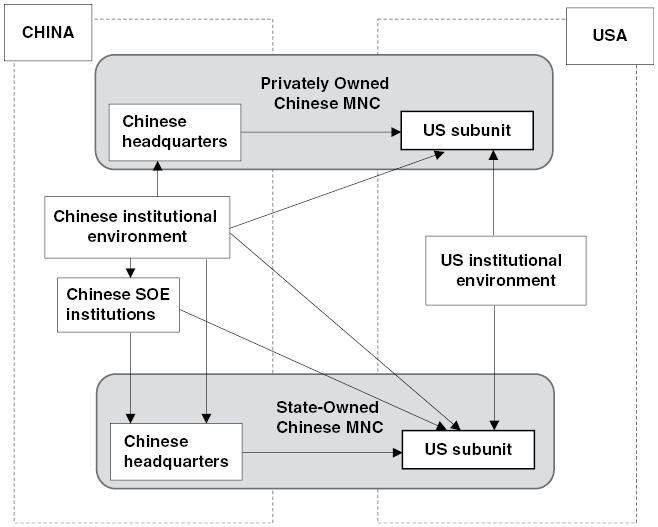

Figure 1.3 illustrates the different sets of home and host-state institutions that will guide the analysis of the interconnected topics in Chapters 2–6: the internal legal capacity of Chinese companies in the United States; their selection of US lawyers and consumption of US legal services; and their dispute resolution and litigation in US courts. Note that the dual institutional environment varies across these different subject areas.Footnote 115 For instance, the dual institutions governing the production and purchase of legal services are related to, yet distinct from, those regulating dispute resolution. Therefore, within the dual institutional framework, the analysis of each subject will commence with a detailed issue-specific institutional comparison.

Figure 1.3 Dual institutional influence on Chinese companies operating in the United States

In summary, this book constructs an analytical model of dual institutional influence and employs it to explore how Chinese companies navigate the complex US legal system. It investigates formal and informal institutions of both the home and the host states while accounting for inter-company variations.Footnote 116 Among the multiple factors that differentiate the Chinese institutional environment from that of the United States, this book pays particular attention to a unique institutional feature: the state ownership of certain Chinese investors. Before proceeding, Section 1.4 below sketches the main characteristics of the broad institutional environment of China, particularly the SOE institutions, to provide readers with the necessary background knowledge and avoid repetition in subsequent topical analyses.

1.4 Home-State Institutional Environment and Institutions for SOEs

The post-Cultural Revolution era witnessed the metamorphosis of China from an impoverished hermit state to the world’s second-largest economy with a relatively open and dynamic market. In this transformative process, business organizations evolved in sync with their legal and regulatory environments. Prior to the economic liberalization, the Chinese government owned and micro-managed most business enterprises,Footnote 117 which suffered inefficiency and incurred continuous losses.Footnote 118 The government experimented with various performance enhancement schemes, yet almost all of them failed.Footnote 119 At the same time, businesses with alternative ownership structures sprouted and, without the organizational weaknesses of the SOEs, proved highly competitive.Footnote 120 Their success enabled the reformers to make the case for a radical reform.Footnote 121

In the mid-1990s, the reformers began the massive privatization of the SOEs,Footnote 122 with the goal of establishing a “socialist market economy.”Footnote 123 A policy of “grabbing the big and letting go [of] the small” was implemented, resulting in the privatization of most small and medium-sized SOEs. The government, however, retained ownership over large SOEs in key strategic sectors.Footnote 124 When the dust settled, a sui generis economic system took shape. A defining feature of the system is a cohort of “modernized” SOEs,Footnote 125 which underwent corporatization and adopted organizational structures resembling contemporary Western firms.Footnote 126 Over time, many of the SOEs have listed their stocks on major securities exchanges in China and abroad.Footnote 127

The Chinese government also adjusted its mode of control over these “modernized” SOEs. First, it consolidated the supervision of the largest national SOEs and delegated it to a newly established agency under the State Council – the State-Owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC). The SASAC functions as both the nominal controlling shareholder and the primary regulator of the national SOEs. Instead of engaging in micro-management,Footnote 128 the SASAC periodically reviews important corporate matters, evaluates senior corporate officers, and makes long-term strategic business plans for the SOEs under its supervision.Footnote 129 The agency is also responsible for implementing rules and regulations concerning the preservation of state assets.Footnote 130 Modeled after the national agency, the provincial and municipal SASACs supervise Chinese SOEs of their corresponding levels in all business sectors.Footnote 131

A sophisticated nomenklatura system enables the state to realize its effective control over the SOEs,Footnote 132 with the central government making personnel decisions over officials of the vice-ministerial or vice-provincial level and above.Footnote 133 Promotion of SOE staff to positions at this level is overseen by the Central Organization Department of the CCP, with the Political Bureau having the final say.Footnote 134 In this process, the SASAC, as the regulating government agency, plays an extensive role.Footnote 135 Apart from the SASAC, other party and state agencies may also assert control over Chinese SOEs either directly pursuant to special rules,Footnote 136 or indirectly through their supervision over SOE employees who are CCP members.Footnote 137

Though transformational in myriad ways,Footnote 138 the SOE reform and the contraction of the state sector are by no means a linear process. The global financial crisis and its aftermath greatly empowered Chinese SOEs,Footnote 139 and the central government has been sending contradictory signals ever since about the intended role of SOEs in the economy. While some top officials insisted on further deepening the market reform,Footnote 140 others charged the SOEs to grow “larger and stronger.”Footnote 141 Meanwhile, the CCP has reasserted its absolute reign over SOEs,Footnote 142 marking a sharp reversal of the previous policy to “separate management from politics”Footnote 143 and further blurring the boundary of the state.Footnote 144

As the Chinese market expanded, non-state-owned business enterprises also grew in number and scale. Though they initially lacked state support and institutional legitimacy, the market reform improved their macro-environment, and some have since managed to achieve global competitiveness, especially in sectors traditionally unoccupied by powerful central level SOEs. Also, an increasing number of privately owned Chinese firms have gone public, enabling state investors to purchase significant equity interest in such firms.Footnote 145

In brief, the market reform of the last few decades gave rise to a distinct economic system, often labeled as state capitalism with Chinese characteristics.Footnote 146 It features government dominance over strategic and important industries with direct ownership control over corporatized SOEs or through policy and regulatory intervention, and an expanding, dynamic market highly integrated in the global economy.Footnote 147

To facilitate the “socialist market economy,” the central government enacted a comprehensive set of new laws and regulations that borrowed extensively from the existing laws and legal principles of the United States and other developed countries.Footnote 148 Despite the convergence in formal laws and legal principles, the laws in action are vastly different between China and the United States. Since the end of the Cultural Revolution, Chinese courts have been undergoing rapid changes. Historically designated as a state instrument for class oppression, the Chinese judiciary had been staffed by loyal veterans without any formal legal education until 1998, when the Law on Judges took effect, requiring candidates for the judiciary to obtain a college degree and pass the national judicial examination.Footnote 149 Concurrent with the professionalization of the judiciary, the number of first instance cases rose dramatically from 906,051 in 1981 to 30,805,000 in 2020.Footnote 150 Meanwhile, the Chinese bar expanded from near non-existence toward the end of the Cultural Revolution to an association of 574,800 practicing lawyers in 2021.Footnote 151 Legal education also bloomed, with tens of thousands of students graduating each year from more than six hundred law programs.Footnote 152 The remarkable progress notwithstanding, the Chinese judiciary remains subordinated to the CCP, and personal connections or the power distribution of litigants, rather than relevant statutes, often determine how lawsuits of political, social, and economic significance transpire.Footnote 153

For much of the reform period, Chinese laws and regulations lagged behind the fast-changing economy and society. To a certain extent, the Chinese experience exemplifies an institutional version of Schumpeterian creative destruction. Risk-taking entrepreneurs pushed porous institutional boundaries with unsolicited and implicit support from the reformers among the ruling elites, who then selectively legitimated and formalized the incremental changes, which motivated further grassroots entrepreneurial experiments. The incessant recursive process gave rise to more market friendly institutions that gradually replaced the rigid Soviet-style planned economy.Footnote 154 However, among the downsides of this institutional creative destruction is an entrenched culture of disrespect for formal rules and procedures and legal uncertainties for social and economic transactions. Embedded in such an institutional environment, Chinese managers often under-appreciate legal and regulatory risks or deal with them in a highly opportunistic manner.Footnote 155

Within this transitional Chinese social setting, actions invoking the application of formal law (e.g., litigation) have acquired ingrained and contextualized extra-judicial meanings. For instance, as just noted, the judiciary’s subordination to political power and the incremental legal reform marginalized the role of Chinese courts in private ordering. Long regarded as an ineffective means of resolving high-stakes disputes, litigation in such an institutional context can be viewed as a sign of incompetence or lack of political resources.Footnote 156 Firms striving to avoid sending such a signal would be reluctant to litigate. Additionally, due to the relatively peripheral role of law, many business transactions in China have relied on relational contracts impervious to formalistic judicial intervention.Footnote 157 In short, depending on the specific context, litigation or the threat thereof contains a variety of socially constructed meanings such as incompetence, hostility, desperation, vindication, or an intent to end a cooperative relationship.

How do firms interact with such a legal system? First, Chinese SOEs may differ from privately owned enterprises (POEs) in this regard. As the Chinese party-state continues to rely on SOEs to implement its policies, raise revenues, and maintain social control,Footnote 158 profit maximization is rarely the primary, or even a prioritized, goal for SOE managers.Footnote 159 The multitasking of Chinese SOEs complicates their management of risks, including legal risks. Moreover, government ownership spawns an acute multiagency problem.Footnote 160 While the separation of ownership and control has long been the hallmark of modern corporations, the misalignment of interests is more severe in Chinese SOEs, as their managers answer to multiple layers of supervising bodies, and none possesses a genuine ownership interest.Footnote 161 The complex agency problem begets suboptimal responses to corporate legal risks. On the one hand, SOE managers heavily discount losses from the companies’ illegal acts and therefore may under-invest in diagnostic and preventive measures such as employing competent in-house counsel. On the other hand, SOE managers may over-invest in mitigating legal risks as cost savings generate no immediate personal benefits, whereas conspicuous breaches of law may reach the public domain and jeopardize their careers. Despite the predictive ambivalence, Chinese SOEs historically under-invested in the management of legal risks,Footnote 162 as their political influence begets favorable adjudicatory bias, providing a layer of protection for the directors and managers.Footnote 163 However, as will be detailed in Chapter 2, the SASAC has taken the management of overseas legal risks more seriously, so how state-owned Chinese MNCs navigates the US legal system remains an open empirical question.

Unlike SOEs, private Chinese companies must maintain a delicate relationship with the state.Footnote 164 Without the political status of SOEs, private companies approach legal risks with an eye on minimizing state intervention and the expenditure of precious social capital. Sizable private firms in China cultivate personal connections with powerful officials, in exchange for protection and favors.Footnote 165 The system builds on the fundamental social principle of reciprocity, so once a favor has been returned, additional investment must be made to replenish the guanxi capital. Thus, savvy business owners would refrain from seeking the intervention of powerful officials in routine legal matters.Footnote 166 Investing in legal risk management enables a business owner to avoid drawing on precious guanxi capital. Hence, demand for legal services has increased, though “know who” ultimately trumps “know how.”Footnote 167 Moreover, managers of privately owned Chinese companies, whose interests are better aligned with corporate profits, take a more pragmatic and efficient approach toward litigation. The efficiency, however, must be understood in the firms’ normative context. Without state ownership, private businesses often need to signal to the market about their adequate resources, status, credibility, and trustworthiness. In a society where informal institutions have assigned complex meanings to litigation, managers of POEs would typically avoid it unless certain socially constructed interpretations are intended, or the costs associated with the interpretations are clearly outweighed by the expected benefits.Footnote 168

To summarize, the institutional environment for Chinese firms has undergone a profound transformation in the past four decades, giving rise to a sui generis model of state capitalism.Footnote 169 In the process, Chinese courts have become relatively more professional, the legal profession has expanded, and the number of lawsuits has surged. Nonetheless, the judiciary remains subordinate to powerful state actors and their affiliates; formal law continues to play a secondary role in business transactions, therefore quality legal services are generally undervalued. All these, coupled with circumscribed authority of the courts, reinforce the culture of legal pragmatism and opportunism, and entrench the social norms attaching complex non-legal meanings to litigation.

Juxtaposing with this is the legal environment in the United States. Relatively speaking, formal laws in the United States assume a more important role in corporate management and business transactions.Footnote 170 US courts, especially those at the federal level, enjoy considerably more independence and authority than Chinese courts. Kagan characterizes the US legal environment as comprising both the “day-to-day practice of adversarial legal contestation,” and “the structures of adversarial legalism,” defined as “a complex of legal institutions, mechanisms, rights, and rules that facilitate or encourage adversarial, party-dominated legal contestation.”Footnote 171 Compared with other economically advanced democracies, not only the “fear of litigation is greater in the United States, but also that litigation really is more common in the United States than in parallel policy areas in the other countries.”Footnote 172 The institutional hallmarks that are part and parcel of the allegedly “unique” lawyer-driven US adversarial system include “ready access to the courts, contingency fees, class actions, large money damages, broad judicial authority to reverse governmental decisions, a politically appointed judiciary, and relatively higher levels of legal malleability and uncertainty.”Footnote 173

The debate has not yet settled on whether adversarial legalism accurately describes the “style” of dispute resolution and regulatory enforcement in the United States, or whether the United States is “exceptional” in that regard.Footnote 174 Recent evidence suggests that the “conservative legal movement” might have alleviated litigation risk for US businesses.Footnote 175 Meanwhile, some evidence indicates that other countries have Americanized in the sense that participatory formal contestations figure more prominently in policy implementation and dispute resolution.Footnote 176 As a matter of fact, one may even consider China as a case in point, where many market-enabling laws contain US legal transplants or neoliberal principles, and Chinese citizens litigate significantly more cases than before.Footnote 177 Nonetheless, as the major institutions undergirding the US judicial system are absent in China, I believe few scholars would seriously contest the claim that legal encounters in the United States are generally more formalistic, adversarial, complex, costly, and lawyer-driven than those in China.Footnote 178 Are Chinese companies able to surmount the vast institutional divide and navigate the complex, unfamiliar host-country legal terrain? The rest of this book will attempt some answers.

1.5 Methodology

This book employs both quantitative and qualitative methods. The primary quantitative evidence comprises two large datasets: a unique set of multiyear survey data about Chinese companies operating in the United States and a set of hand-collected federal litigation data involving a large sample of Chinese companies. Since 2014, I have been collecting annual survey data from Chinese MNCs’ US subunits in collaboration with the China General Chamber of Commerce USA (CGCC), by far the largest association of Chinese-invested businesses in the United States.Footnote 179 Its membership moved roughly in proportion with the number of Chinese companies in the United States during the surveyed period, so did the size of the survey sample. In 2017, for example, the questionnaires were sent to about 600 CGCC members, and 213 responded (a response rate of approximately 35.5 percent). From 2014 to 2019, the survey response rate remained relatively stable. Due to COVID-19 and the deterioration of US–China relations, the response rates dropped to about 27 percent for the 2022 survey. The sample size also shrank as some Chinese companies have chosen to exit the US market. Comparisons between the responding and non-responding companies revealed no significant differences in major aspects of the firms such as business size and ownership structure. Meanwhile, a comparison with US-investing Chinese firms registered with the Ministry of Commerce of China suggests that large businesses and SOEs are over-represented in the CGCC sample.Footnote 180 This serves well the purposes of this book, as state ownership is a key variable of interest and some of the topics such as in-house legal capacity are pertinent only to sizable Chinese investors. The job titles of the respondents vary, with the vast majority being CEOs, CFOs, general managers, presidents, and representatives.

Each of the survey questionnaires contained a wide range of questions, a portion of which were repeated every year (e.g., location, year of entry, investment plan) to gauge key aspects of the Chinese companies, others were included in only one or two surveys due to shifting preference and focus of the CGCC and its board members.Footnote 181 Hence, most of the in-depth analyses in the following chapters rely on data from selected years. To be more specific, Chapter 2 analyzes the 2019 and 2022 data to understand the in-house US legal management at the Chinese companies, and statistically tests the 2019 data to investigate the inter-company variations. Chapter 3 examines the 2017 data for lawyer selection preferences, and the 2019 and 2022 data for legal service purchases. Chapter 4 investigates the 2014, 2017, and 2018 survey data for insights about the companies’ litigation preferences and their US litigation experiences. Chapter 5 studies the dataset of federal lawsuits involving all Chinese companies that had responded to the 2019 CGCC survey. More details about the hand-collected litigation data can be found in that chapter. Last, Chapter 6 investigates the firms’ contemplation of litigating against perceived mistreatment by the US government by analyzing relevant data from the 2014, 2015, 2016, and 2017 surveys, and examines their actual coping measures with data from the most recent 2022 survey.

In addition to the quantitative evidence, this book draws upon a wealth of qualitative data to analyze how Chinese companies navigate legal challenges in the United States. The qualitative evidence includes 176 interviews with knowledgeable informants, such as business executives, in-house counsel, lawyers, and consultants employed by Chinese companies. These interviews were collected using a multisource snowball sampling method, which generated a sizable sample of professionals with diverse backgrounds (see Table 1.1 for more details). Personal acquaintances, who are professionals working for Chinese businesses in the United States, comprised one core group of the interview subjects. They shared valuable insights and introduced more interview candidates. Another cohort consists of CGCC members, some of whom also tapped into their personal and business networks to recruit potential interviewees for this project. In addition, interviews were conducted at various panels, workshops, and conferences on law and foreign investment.Footnote 182 Together, the interviews substantiate the varying dual institutional influence as manifested in different subject areas to be explored in this book, assist in the generation of testable hypotheses, and make sense of the statistical findings. To supplement the interviews, I also collected and analyzed a large number of legal archives, media reports, corporate filings, publicly available personal profile information, and other secondary materials. In summary, research based on the combined quantitative and qualitative data enables a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of how Chinese companies address legal challenges and navigate the complex legal landscape when operating in the United States.

Table 1.1 Background of interviewees

| Managers | In-house counsel | Lawyers | Consultants | Others | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 73 | 21 | 65 | 13 | 4 | 176 |

1.6 Conclusion

Numerous Chinese companies have established a significant foothold in the United States, immersing themselves in its complex, rigorous, and adversarial US legal system. The ways in which they negotiate the omnipresent, consequential legal risks, however, remain under-explored. To begin to address this deficiency, this chapter constructed an overarching theoretical framework of dual institutional influence and canvassed the relevant institutional contexts of both China and the United States, underscoring their stark contrasts.

Within the dual institutional framework, the following chapters will sequentially investigate four interrelated topics: (i) the internal legal capacity of Chinese companies in the United States; (ii) their selection of US lawyers and acquisition of US legal services; (iii) their dispute resolution and litigation experiences in US courts; and (iv) their legal reactions to perceived discriminatory practices by US government agencies. Each chapter will begin with an in-depth examination of both the home-state and host-state institutions pertaining to the relevant subject area. Following the institutional comparison, it will analyze the survey and interview data to discern how the dual institutional influence impacts Chinese companies operating in the United States as they navigate the intricate US legal system. Further, each chapter will perform statistical tests to elucidate inter-company variations and to identify potential correlations between key institutional factors (e.g., state ownership and cultural difference) and the preferences and actions of these Chinese companies. As one experienced US lawyer observed about the seemingly irrational legal strategies of his Chinese clients, “these clients are not stupid. They choose what they think is the best solution within the U.S. and the Chinese contexts.”Footnote 183