This chapter deals with a curious scribal feature prominent in two Nag Hammadi codices: the appearance of diple and coronis signs in the margins of the texts, either alone or in a row. On the few occasions these signs have been noted and discussed by scholars engaged with the Nag Hammadi texts, they have been described, or perhaps rather explained away, as paragraph markers. As this chapter makes clear, however, there is not much supporting the interpretation that the small arrow-like signs in both the left and right margins appearing in some of the texts are paragraph markers. Rather, it is argued here that these signs in Codex I and Codex VIII were markers made by a reader or the scribe himself to highlight passages of particular importance. Furthermore, it is argued that the context in which the marked passages make the most sense is that of a Pachomian monastery in the late fourth or early fifth century.

Ancient Christian Scribal Practice and the Use of Diplai

Christians used a number of scribal signs meant to aid the legibility and study of a text: paragraph markers in the form of enlarged letters; initial lines protruding into the margin (called ekthesis); diaeresis markers, dots above vowels to indicate where one word ends and the next begins; as well as aspirations and breathing markers. Another scribal sign, or perhaps reading sign, with a more elusive function was the paragraphi cum corone, or simply coronis, written somewhat like the letter tau with a tilting base, a parallel line with a diagonal vertical stroke drawn from its middle down to the left side. Corone were chiefly used as paragraph markers but could also highlight passages of particular importance. The diple sign, written like a pointed bracket or an arrow (>), has an even vaguer background. Greek scribes are said to have used the diplai markers for a number of reasons: in order to highlight passages in a text which contained quotations from another text, for example, or for marking out important passages with paratextual relevance.Footnote 1 This practice was adopted by Christian scribes to varying degrees, as scholars have noted previously.Footnote 2 In the earliest Christian manuscripts containing the New Testament writings, the diplai signs were used to mark out passages quoting the Hebrew Bible.Footnote 3 Charles E. Hill writes that he has not found any Christian texts from antiquity where this sign is used in any other way than to quote Scripture.Footnote 4 However, as we shall see, none of the passages highlighted in the Nag Hammadi texts by one or more diple signs being placed in the right or left margins are quotes – or not, at least, of any texts known to us today, Christian or otherwise. However, as noted, diplai were also applied for other purposes, although New Testament scholars have not expanded upon their Christian use. Eric Turner notes in his work on the codicology of Greek manuscripts that a diple was used to mark passages, words or phrases of particular importance, to indicate a parallel or reference or to mark out a passage which is further elaborated on in a commentary in the scribe’s possession or one that is in the process of being made.Footnote 5

Let us turn to the Nag Hammadi texts showcasing the diplai and corone signs.

Scribal Signs in the Nag Hammadi Codices

It has been estimated that twelve different scribes were involved in producing the Nag Hammadi codices, chiefly by identifying the particulars of the scribal hands.Footnote 6 Many, although far from all the texts contain scribal signs, including punctuation, diaeresis, ekthesis, spacing and enlarged letters, among others, that one would expect of ancient manuscripts from this age and context. Such signs were most likely meant to aid legibility, to ease the tracking of the text when reading it (most probably aloud). However, given the existence of some very cluttered pages as well as texts without any scribal markings at all (like The Treatise on the Resurrection in Codex I, discussed in the previous chapter), legibility was far from the first priority for all scribes. Facilitating the reading or performing of the texts in communal settings by a lector was, thus, most likely not their chief purpose. Rather, examination of the scribal signs found in the texts indicates a better fit with a scenario in which the texts were copied for private use: for study, contemplation, educational purposes and discussion.

The corone signs appear in Codices III, V and VIII. As René Falkenberg has pointed out in his study of the sequence of the texts in Codex III (from a codicological perspective), a coronis by itself does not give much information about its function.Footnote 7 Usually they are used as paragraph markers but to ascertain this one is dependent on the context, coupled with other paratextual features. Their use in the Nag Hammadi codices remains to be systematically studied. The diplai (>) and the diple obelismene (>—) have also received unreasonably little attention. Studying these signs carries great potential for aiding us in determining who actually read these texts and why.

Found in most of the Nag Hammadi codices, the majority of the diple signs are situated at the far-right edge of a line to make the margin straight or at the bottom of a page or a text, to complete the last line of a text/page. Thus, the diple sign was first and foremost used as a line filler and for marking off passages and ending pages. In these cases, the diplai are simply used for aesthetic purposes and for lucidity.Footnote 8 The coronis, or paragraphi cum corone, as its name indicates, is most often thought to be a paragraph marker. But closer study of the Nag Hammadi codices shows that the coronis is not used only as a paragraph marker, nor can the diplai be reduced to simple line fillers.

On some occasions, like in Codex VIII, we find coronis marks that cannot be paragraph markers, since they are found within a narrative. We also find diple signs in the margin of texts that do not seem to have the function of being a line filler, since the marks protrude into the margin (and thus serve the opposite purpose of a line filler).Footnote 9 These are found in Codex I. They, too, appear in the middle of a narrative and cannot have been used as paragraph markers. Kasser suggested that the diplai in Codex I could have been used to indicate quotes, as in other early Christian texts, for example quotes from Scripture, but the passages so marked are not from any known Scriptural text. The same is the case with the coronis, excluding its use as a quotation marker. Kasser also suggests that the markings in Codex I could indicate passages of particular importance. Let us study these cases in detail, first the diplai in Codex I and then compare them to the corone sign appearing in Codex VIII and see what the use of these signs can tell us about their readers and how they were read.

The Diplai in Codex I

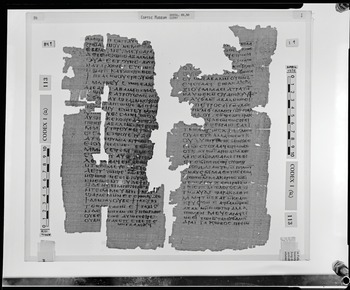

The diple sign is used throughout Codex I and, as stated above, most are line fillers and markers to end a page/text. But in the following places, the sign is not a line filler, nor does it highlight when a text or page ends: 68:19, 75:32–34, 82:2–3, 82:10 83:21, 84:11–13, 119:23–27.Footnote 10 Three of these instances are pages where just a single diple has been placed next to the margin (68:19, 82:10 and 83:21). The single lines highlighted in this way do not form complete sentences, nor are they indicators of the beginning of something new in the narrative. The lines before 68:19 tell us how the Aeons are expected to honour the Father with a certain sentence; then follows the diple line, ‘It is the Father who is the All’ (ⲡⲓⲱⲧ· ⲡⲉ ⲡⲉⲉⲓ· ⲉⲧⲉ ⲛ̄ⲧⲁϥ ⲡⲉ· ⲛⲓⲡⲧⲏⲣϥ̄) (68:18–19). This is too short to ascertain if it is a quote from another text or just a mark made by a reader to note the sentence, perhaps agreeing with what has just been read. We find the same thing in 83:21, which reads, ‘glorious pre-existent one’ ([ⲧ]ⲁⲉⲓⲁⲉⲓⲧ· ⲉⲧⲣ̄ ϣⲁⲣⲡ̣̄ ⲛ̄ϣⲟⲟⲡ·). Both of these diplai occur in the middle of a narrative and highlight passages that underline the greatness of the highest Father, a noteworthy topic for a Christian reader. At 82:10, a diple is placed at the end of a passage but not as one would expect, to mark the place where something new starts, but rather to mark off a sentence that ends the previous passage. The diple is placed next to a line that is drawn inward from the left margin, marking out a sentence beginning and ending with ϫⲉ, between which we read, ‘All his prayer and remembering were numerous powers according to that limit. For there is nothing barren in his thought.’Footnote 11 It is hard to decipher a more detailed purpose behind marking out these single diple sentences. There are, however, four instances in The Tripartite Tractate where multiple diplai have been placed in a vertical row next to the margin, marking out longer passages (75:32–34, 82:2–3, 84:11–13 and 119:23–27) (see Fig. 4.1).

As mentioned in the previous chapter, two of these vertical rows of diplai (p. 119 and, even more clearly, on p. 84) must have been inserted by the scribe himself,Footnote 12 since they do not protrude into the left margin, as one would expect if they were added post-inscription (see Fig. 4.1). On pages 75 and 82 the case is less certain. On page 75 the markings are on the right side of the margin, which is rare for this scribe, so it is possible that they were added by a later reader. In the case of page 82, lines 2 and 3, the diplai are placed next to the left of the text, as ekthesis.Footnote 13 The two lines do not extend as far to the left as the surrounding lines, suggesting that the diplai were added by the scribe when copying the text.

What is the meaning of these markings?Footnote 14 In the following section I examine these four instances where it is obvious that we are not dealing with paragraph markers (because there is more than one diple in the margin), quotes (they are from no known text) or line fillers (all except one are found in the left marginFootnote 15).

Multiple Diplai in The Tripartite Tractate (NHC I,5)

At 75:32–34 we find three diplai in the right-hand margin marking the following passage:

This sentence describes the nature of the Logos, and page 75 as a whole marks the entrance of the Logos, the main character of the narrative in The Tripartite Tractate.

Lines 82:2–3 have two diplai in the left margin, marking a passage on the return of the Logos after his fall from the harmony of the Pleroma. The marked-out sentence reads, ‘It was a help, causing him to turn toward himself’,Footnote 17 referring to the ‘prayer of the blending’ (ⲡⲓⲥⲁⲡⲥ̄ ⲛ̄ⲧⲉ ⲡⲓⲧⲱⲧ̣), mentioned on the line before. ‘Blending’ (ⲡⲓⲧⲱⲧ) is a technical term used throughout The Tripartite Tractate to refer to rejoining the harmony of the Pleroma, Christ and the unity of the spiritual Church.Footnote 18 And, as we have seen, praying has previously been highlighted in the text as of particular importance (82:10). There is a third diple a few lines further down, between lines 9 and 10, marking off a whole paragraph that starts with the Logos turning towards himself. The passage as a whole reads:

Again, prayer is discussed. Here we are told that the Logos turns towards himself, prays and then remembers his previous life with the Totality (the harmony with other Aeons), and the Totality in turn remembers him. These events contribute to the Logos’ return to harmony.

Lines 84:11–13 have a diple beside the first letter in the left margin, and all three are in line with the text in the body, which indicates that they were written by the original scribe and were meant to be included in the text from the beginning. The sentences on these lines comment on the emergence of the different beings created in the aftermath of the fall of the Logos. We read:

Here we encounter an explanation of how the angelic orders above humanity emerged, later called those on the left and the right; they were drawn down after the fall of the Logos into certain natures and substances that resulted in a perpetual conflict within the angelic world.

The last section marked off is at 119:23–27, and here the diplai are found in the left margin. This passage discusses another important subject in The Tripartite Tractate: the psychic race. The pneumatics are described as those who react immediately to the appearance of the Saviour; these people are the natural leaders of the Church and described as the teachers (116:17–20). The role and identity of the psychics is uncertain. However, the lines marked off with diplai make things a bit clearer:

This is a crucial passage in the text. Here we learn that the psychic humans will receive a ‘complete escape’ but that they are drawn to both good and evil on account of the ephemeral nature of their situation. Later in The Tripartite Tractate we read that the psychics have to prove themselves by doing good works and acting as instructed by the pneumatics (131:22–34).

In conclusion, the passages marked off with more than one diple sign can be summed up in the following way:

Elucidating the Monastic Connection of the Diplai Passages in Codex I

All these topics, particularly those highlighting the need for prayer and the passage on page 84 commenting on angelic warfare,Footnote 22 would have spoken to ascetics involved in early Egyptian monasticism.Footnote 23 The passages also deal with details pertaining to Valentinian theology (e.g. those on the youngest Aeon and the psychic race), technicalities that are not spontaneously associated with monks. However, we know that several Church Fathers read Valentinian works and some wrote long treatises about and against them, including two of the most famous early Christian theologians, Origen and Clement, who were in turn read by monks.Footnote 24 It is not unthinkable for monks to have shown interest in forms of Christian theology that Origen and Clement discussed at length and sometimes even upheld, texts that also coincided with what was classified as Origenist theology.Footnote 25 As many scholars have pointed out, The Tripartite Tractate corresponds with Origen’s thought on several points: on the doctrine of apokatastasis; seeing the Will of the Father as the origin of creation; the pre-existence of souls before the body; a resurrection without the physical body.Footnote 26 But what could have spoken to a monastic reader in the parts highlighted with diplai (except the clear monastic topics of prayer and angelic warfare)?

The youngest Aeon is called Logos in The Tripartite Tractate, but in Valentinian theology the youngest Aeon is more often called Sophia, as in The Interpretation of Knowledge and A Valentinian Exposition, which were copied by the same scribe who copied The Treatise on the Resurrection in Codex I.Footnote 27 The passage marked off at 75:32–34 could have been read with special interest because here the Logos is an offspring of Wisdom (Sophia). The doctrine that the Logos, identified with the Wisdom of God, carries out creation according to the providence of God (as it is described in The Tripartite Tractate) would not have sounded strange to a reader familiar with John’s prologue, and even less strange to one who had knowledge of the writings of Philo and Origen.Footnote 28 There are, of course, also points of departure. For example, Origen would likely have opposed The Tripartite Tractate at the same point where he opposed Heracleon, who made the distinction that the Logos created ‘all things’ (Joh 1:3) outside the Pleroma.Footnote 29 But there are clear similarities and points of comparison which in all likelihood would have intrigued Christian readers favouring Origen and the theological intricacies of these cosmological questions.Footnote 30 Furthermore, reading texts with which one does not fully agree is not necessarily less alluring, interesting or edifying than reading something which affirms one’s opinions.

The passage marked off at 82:2–3 also deals with the Logos and describes how the youngest Aeon is returned to the fold from which he fell away by turning towards himself, praying and with the aid of remembrance. This is a part of the text where Valentinian theology coincides with what we know was of interest to early Christian monks in Egypt, perhaps in particular those reading Origen. At 82:2–3 we read of how introspection and prayer led to salvation, which is described as a ‘blending’. The term apokatastasis is used in The Tripartite Tractate (123:19–27, 133:6–7) in the same way as it was presented by those whom we know supported the doctrine, such as Origen and Evagrius (as a return and integration into a whole).Footnote 31 Furthermore, the notion of the Logos’ ‘turning towards himself’ (82:2–3) would have sounded very familiar to monks engaged in introspection in order to be afforded visions, and who employed mnemonic techniques for reciting Scripture when praying or warding off demons or unwanted emotions and cravings.Footnote 32 There was also a widespread idea among early Christians, especially in the early monastic world of Egypt, that earthly rituals corresponded with angelic rituals in heaven, that angels could aid humans and that humans could gain powerful support through introspection and the visualisation of heavenly domains.Footnote 33 Thus, monks reading about the Logos turning towards himself and experiencing communion with the heavenly beings above through prayer, remembrance and introspection would have found it familiar indeed.

The Origenist controversy at the turn of the fifth century coincided with the ban on not just Origen’s writings but on other material which the victors of the ecclesiastical struggles considered potentially harmful, like apocryphal books.Footnote 34 However, these materials seem to have persisted in monasteries long after the ban had been imposed.Footnote 35 Why were monks not allowed to read apocryphal material and Origen? Some actually believed that apocryphal books were edifying if approached correctly,Footnote 36 but several authorities in the early monastic period expressed concern that not everybody could handle material that was considered speculative.Footnote 37 It was thought that those who did not possess the necessary knowledge and firmness of faith would be led astray by what they read.

The Tripartite Tractate’s anthropology is structured around a hierarchy of different levels of knowledge.Footnote 38 The passage marked by diplai at 119:23–27 mentions the psychics. The version of Valentinian anthropology that envisioned three separate human ‘races’ (pneumatics, psychics and material) was well known to several Church Fathers and the distinction would not have sounded alien to someone familiar with Scripture and ancient physiology and theory of emotions.Footnote 39 What we encounter in The Tripartite Tractate is most likely an adaptation of Paul’s comment on different kinds of Christians (1 Cor 2:6–16), which in turn drew on contemporary philosophy and anthropology. People were thought to comprise a material part, a psychic part animating the material and a pneumatic (sometimes referred to as noetic) part which gave life to the psyche (soul).Footnote 40 In 1 Corinthians (2:6–16) Paul makes a distinction between pneumatic Christians who had the ability to grasp spiritual wisdom and psychic Christians who did not understand this higher form of knowledge. This idea that some people have spiritual gifts and some do not is also found in The Interpretation of Knowledge (15:10–19.37), but in The Tripartite Tractate the distinction between pneumatics and psychics (and hylics) is framed as one between fixed human categories.Footnote 41 In The Tripartite Tractate we read that the pneumatics ‘are the apostles and evangelists, the disciples of the Saviour, and they are teachers of those who need teaching’.Footnote 42 The psychics are those who were ‘instructed by voice’ (ϩⲓⲧⲛ̄ ⲟⲩⲥⲙⲏ ⲉⲩϯⲥⲃⲱ)(119:3), while, according to the apostle Paul, spiritual teaching was to be distinguished from human wisdom (1 Cor 2:13–14). We are told in The Tripartite Tractate that the pneumatics are ‘instructed in an invisible manner’ (ⲟⲩⲙⲛ̄ⲧⲁⲧⲛⲉⲩ ⲁⲣⲁⲥ ⲁϥⲧⲥⲉⲃⲁⲩ) by the Saviour directly (115:1–2).Footnote 43

Many monks would undoubtedly have thought in similar ways. The idea that there are people with spiritual gifts and that there are degrees of knowledge was a common theme among monastic writers. Evagrius writes prolifically about the different stages of learning and degrees of knowledge, between outside knowledge which is reasoned with words and a higher form of knowledge which is revealed directly to the mind.Footnote 44 He cautions, therefore, that reading literature of a certain kind can be dangerous for the novice: ‘It is not necessary for the knowledgeable to tell the young anything, nor to let them touch books of this sort, for they are not able to resist the falls that this contemplation entails.’Footnote 45 Evagrius, like many other monks before and since him, emphasises that teaching and learning is directly related to spiritual warfare.Footnote 46 In The Tripartite Tractate the distinction between pneumatics and psychics also seems to be related to the topic of spiritual warfare.Footnote 47 We read that pneumatic people have come to this world ‘that they might experience the evil things and might train themselves through them’.Footnote 48 The operative word here is ⲣ̄ⲅⲩⲙⲛⲁⲍⲉ (γυμνάζω) which is a word used in patristic sources for the exercise of Christian life,Footnote 49 especially higher spiritual life and moral perfection.Footnote 50 However, in a monastic context ⲣ̄ⲅⲩⲙⲛⲁⲍⲉ is also used to refer to preparing to withstand attacks by evil demons, as in The Life of Antony.Footnote 51 In The Tripartite Tractate 119:23–27, we read that even psychic people, those who are not made to fight evil, will receive full salvation, a concept that surely would have been a comfort to monks who did not have the stamina of a spiritual warrior like Antony, who spent time alone in the desert grappling with evil demons. This corresponds closely with what has been argued by Elaine Pagels and Lance Jenott, that there is a close correlation between Codex I and the Letters of Antony (where Antony is also engaged in battle with demons).Footnote 52

These readings of the passages the scribe has highlighted in The Tripartite Tractate should suffice to demonstrate that they would have spoken to many monastic readers. The diplai-highlighted passages, discussing angelic warfare, the Logos and the psychics – which should be read as biblical interpretation and allegory (of Genesis 6, the Gospel of John and Paul’s letters, for example) – would undoubtedly have interested monks. But what can all this say about the particular monks who used the Nag Hammadi texts? As it happens, the diplai and other scribal markings we find in Codex VIII lend themselves to this discussion.

The Scribal Signs in Codex VIII

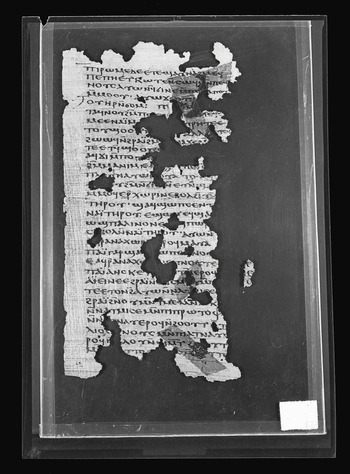

Codex VIII comprises a single quire of a total of 74 leaves, with only two texts between the covers. Most of the content consists of the text entitled Zostrianos, the longest tractate in the Nag Hammadi collection, concluding with a short text, The Letter of Peter to Philip. Codex VIII is in a badly fragmented state. Most of the damage is to the bottom of its binding area, especially in the right margins of the lower left sides of the pages and the lower half of the left margins of the right-side pages. There are markings of two different kinds in the left margins throughout the codex: lateral strokes (–), most often between two lines, and a forked marking not unlike the shape of a diple. While the diple signs from Codex I are written like the tip of an arrow, the forks in Codex VIII are most likely corone signs made to highlight a passage of particular interest or importance to a reader/scribe. While the diplai in Codex I were placed vertically next to the left margin – some completely in line with the margin, indicating that they were made by the scribe himself to mark out a passage – the markings in Codex VIII are placed next to or between two lines, which does not help us identify whether they were penned by the scribe or a later reader. The ending of a marked-out passage is indicated with the use of either a lateral stroke in the margin or dicola inside the text.Footnote 53 Let us now turn to see what these highlighted passages contain and whether a reason can be discerned for why they were highlighted, beginning with the longest text: Zostrianos.

Zostrianos (NHC VIII,1)

From the outset we might consider the fact that the texts that were deemed interesting enough – or perhaps complicated enough – to warrant the reader’s/scribe’s making notes in the margin are the two longest and more complex in the Nag Hammadi collection. The first instance of scribal and/or reading aids/markings in Codex VIII appears on page 26. Between lines 18–19 a coronis sign is found in the left margin, and after the first word on line 19 we find a colon. The passage which precedes the colon highlighted by the coronis and colon is a section dealing with the structure of the highest realm and the role of the different characters responsible for its creation and organisation. The lateral stroke in the margin followed by the colon marks the beginning of a discussion about souls whose first sentence reads, ‘Do not be amazed about the differences among souls’ ([ⲉ]ⲧⲃⲉ ⲧⲇⲓⲁⲫⲟⲣⲁ ⲇⲉ ⲛⲧⲉ ⲛⲓⲯⲩⲭⲏ [ⲙ]ⲡⲣⲣ).Footnote 54 The topic, as John Sieber mentions in the NHMS edition,Footnote 55 is an important theme in the text. What are the differences between souls, which souls are saved and which are not, and why? As we have seen, this topic was also highlighted in Codex I. The discussion of the differences in souls appears again in the next highlighted passage in the text.Footnote 56 In the left margin of page 30, between lines 9 and 10, we find a lateral stroke as on page 26, this time with a colon appearing five lines later.Footnote 57 The marked-out sentence begins, ‘The son of Adam, Seth, comes to each of the souls as knowledge suitable for them.’Footnote 58

Unfortunately, a coronis and two lateral strokes in the left margin (at 32:5–6, 36:16–17 and 40:5–6) are found in a badly fragmented section of the text which makes it hard to discern the content of these lines. However, the lateral line on page 32:5–6 is followed by a section mentioning the words ‘every […] of his soul’ (ⲟⲛ […] ⲛ[ⲓ]ⲙ ⲛⲧⲉ ⲧⲉϥⲯ[ⲩ]ⲭⲏ) (32:17–18). Page 36 mentions the divine beings Barbelo and Kalyptos shortly after a lateral stroke in the left margin between lines 16 and 17. At 40:5–6 a line is found in the left margin, mentioning knowledge and Protophanes.

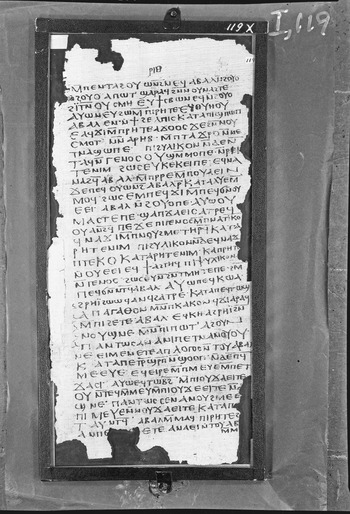

The next legible scribal markings are found on page 44. The first four lines are clearly marked out by a lateral stroke above the first line on the page and a coronis below line four, marking out the beginning of a new passage (see Fig. 4.2). The first word on line five is also included in this passage, as it is followed by a colon and a space. The passage reads as follows:

Figure 4.2 Page 44 in Codex VIII, illustrating a pronounced coronis in the left margin between lines 4 and 5, followed by a colon in line 5. At the top of the page, we find a lateral stroke which is used together with the coronis and colon to mark out a particular sentence.

The coronis between lines 4 and 5 indicates that this is the beginning of a new section in the text. What follows gives details about the topic of the marked-out passage in which we learn that those who are saved have the possibility to pass through the obstacles and become united with God above.

On the next page, page 45, the first six lines are highlighted. As far as one can see, this is the only right-side page in Codex VIII where a coronis is placed in the left margin. There could well have been others, but due to the bad fragmentation that has generally been inflicted on the left margin on most of the right-side pages, we cannot determine how many. Above the first line on page 45, we find a coronis in the left margin and six lines later a colon has been placed between two words. The passage runs as follows:

This passage seems to continue the theme of the differences among souls and details of who will and will not be saved. Following this is a passage wherein the divine character Ephesech explains why there is a multiplicity of forms in the world, saying that it is because substances turn inward towards themselves, become separate and seek things that have no existence, instead of uniting and becoming one. This causes devolution and birth, and even though the substance is immortal it becomes trapped in the material body (45:11–46:15). This is why powers (ⲛⲁϭⲟⲙ) have been placed in the world to save the immortal substance that becomes trapped.

The next legible reading sign does not appear until twenty pages later on page 64, line 13. This marks the ending of a detailed passage describing how Zostrianos corresponds with different characters. It ends with an admonition to the author: ‘Zostrianos, [learn] of the things about which you asked’ (ⲍ̅ⲱ̅ⲥ̅ⲧ̅ⲣ̅ⲓ̅ⲁ̅ⲛ̅ⲉ̅ ⲥ̣[ⲱⲧⲙ] ⲉⲧⲃⲉ ⲛⲏ ⲉⲧⲕⲱⲧ̣[ⲉ ⲛ]ⲥⲱⲟⲩ).Footnote 61 After this follows the new passage discussing the immortal and undivided spirit. The following page is damaged and we cannot see where the marked-out passage ends.

On page 80, line 11, a lateral stroke has been placed in the left margin, followed by a colon seven lines later. If this were a paragraph marker, as some have claimed,Footnote 62 one would have expected the coronis to have been placed next to the line with the colon, making it clear that this began a new section, as in the example from page 64. It is more likely, however, that, again, we have a partial passage marked out for particular interest. The marked-out lines on page 80, which unfortunately are fragmented in the right margin, run as follows:

Again, it is the all-powerful Spirit which existed before anything which is discussed in this marked-out passage, just as in the marked-out passage on page 64. Following this, the text turns to describing how the invisible Spirit has never been ignorant, that it is Barbelo who begets error and becomes ignorant.

Before summarising the topics in the above marked-out passages, let us briefly survey the second text in the codex where we also find the markings: The Letter of Peter to Philip.

The Letter of Peter to Philip (NHC VIII,2)

The last nine pages of Codex VIII contain The Letter of Peter to Philip, a section of the codex that is comparatively well preserved and legible. On the first page (132), a diple is found in the left margin at line 21, the only place where a diple is placed where we would have expected a coronis. It is faint but visible and marks out the following sentence: ‘Preach in the salvation!’ (ϣⲉ ⲟⲉⲓϣ ϩⲣⲁⲓ ϩⲙ ⲡⲓ[ⲟ]ⲓϫⲓ̇) (132:21). The next line reads, ‘which was promised us through our Lord Jesus Christ’.Footnote 64 This is a single line being highlighted and not a shorter passage, and suggestively, this is the reason the diple has been used instead of a coronis, which is placed between two lines and not next to a line.

On page 136 we find a shift in the narrative, which is marked with a coronis between lines 15 and 16. The last word of the previous line ends with a colon, indicating the beginning of a new passage. The previous passage has dealt with the Demiurge who, with the help of his minions, creates the visible world, while that marked by a coronis begins a new theme in the story, providing information about the Saviour who steps down into the body. This is a clear instance of a paragraph marker.

On page 138 we find one clear lateral stroke in the left margin, without any colon in the text.Footnote 65 This could signal that it was added by someone other than the scribe or that the marking is used (by the scribe or a later reader) to highlight a sentence or section of particular interest. The previous passage describes demons attacking the ‘inner man’, and the reader is encouraged to fight evil powers by teaching in the world. This topic reconnects to the marked-out sentence on the first page of the text, where a diple highlights a call for the disciples to teach in the world. The marked-out sentences on page 138 deal with a related matter, namely, the worldly results of Jesus’ recommendation: suffering of a different kind. The sentence reads, ‘If he, our Lord, suffered, how much (must) we (suffer)?’Footnote 66 This quote paraphrases and connects with several key passages in Scripture (perhaps most obviously 1 Peter 2:21) and is one of the very few (if not the only) marked-out sentences that clearly does so. Keeping in mind that the prior passage called for the disciples to teach in the world (which echoes the admonition in the marked-out sentence on the first page of the text), it would seem that what we have here is a reaction to the consequences of imitatio dei.

The last page of the text (140) contains, at a quick glance, several markings in the margin; however, only one of them, between lines 14 and 15, is clearly a scribal or reading sign. This time it is hard to determine if it is a paragraph marker or something else. Line 15 does contain a colon marking out a new passage, yet it is not a coronis in the margin followed by colon, as on page 136, but a straight lateral line. It could have been added at a later time by someone other than the scribe or mean something other than a paragraph marker. It appears just before the final episode of the text and thus could be a sub-paragraph or meant to emphasise the words of Jesus which follow at the marked-out place: ‘Peace to you [all] and everyone who believes in my name. And when you depart, joy be to you and grace and power. And be not afraid; behold, I am with you forever.’Footnote 67

Summarising the Markings in Codex VIII

Are the many markings found in the margins of Codex VIII simply paragraph markers, as Layton, for example, has suggested?Footnote 68 As we have seen, there is much that would indicate that there is something entirely different going on. From a quick overview of the way the markers are employed (see Table 4.1), it becomes obvious that they are not used uniformly and, in fact, deal with a multitude of themes.

Table 4.1 Scribal markings in Codex VIII

Zostrianos makes up most of the codex and this is without doubt one of the more complex narratives in the entire Nag Hammadi collection. It is a long and very detailed text, whose background many scholars have tried to elucidate. In 2013, Dylan Burns wrote the following about previous studies of Zostrianos:

Research into Zostrianos has focused on its metaphysics and relationship to contemporary ‘Pagan’ thought, leading a vast majority of scholars to regard it as a ‘Pagan’ apocalypse, perhaps even designed to appeal to contemporary Greek philosophers. Yet an attentive reading of its frame narrative and routine investigation of its characters’ backgrounds in Greco-Roman literature leads one to consider instead a milieu for Zostrianos that is deeply colored by contemporary Jewish and Christian apocalyptic literature, even rejecting the authority of Hellenic tradition.Footnote 69

Burns’ study draws much-needed attention to the Christian influence in this text, while, as he writes, previous scholarly interest has chiefly focused on the text’s relation to pagan philosophy.Footnote 70 Drawing attention to Zostrianos’ similarities to Christian theologoumena also provides us with much-needed contextualisation for Codex VIII as a whole. Taking these factors into account, a Christian context which speaks readily to many of the marked-out passages discussed above is certainly the monastic one. To demonstrate this, in the following section I situate the passages discussed above in relation to the activities transpiring in Pachomius’ monastery, as told to us by a certain bishop named Ammon.

The Letter of Ammon Read in Light of Codex I and Codex VIII

There are from the outset key aspects in the frame story of Zostrianos which bring to mind a monastic setting, or at least an ascetic one. The text is portrayed as the words of a disillusioned seeker of spiritual growth, Zostrianos, a person who sees himself as one of the elect placed on earth to teach others and to develop his spiritual knowledge. Yet he is so dissatisfied with his worldly context that he draws away into the desert: ‘I became terribly upset and felt depressed about the small-mindedness that surrounded me. I dared to do something, and to deliver myself unto the beasts of the desert for a violent death.’Footnote 71 An intellectually curious Christian monk would undoubtably have found the text of interest, especially the many similarities which the frame narrative has with monasticism. The codex’s second text preaches on what is presented as the duty of Christians to spread the word of God and accept the suffering bestowed by imitatio dei, along with numerous references to the struggle against evil spirits and the need to protect oneself against their onslaught by standing firm and speaking the truth. To take on the suffering of being a devout Christian, especially one who devotes his or her life to spiritual growth and spreading the word of God, is, as we know, a recurring theme in monastic literature.

To illustrate how well the marked-out passages fit into the monastic world, particularly a Pachomian environment, let us familiarise ourselves with the opening passage of The Letter of Ammon. This text, it is stated, is written by a certain bishop named Ammon to a fellow bishop who had requested that Ammon tell him of his three years living as a Pachomian monk at the monastery at Pabau, at the time under the leadership of Pachomius’ predecessor Theodore (314–368).Footnote 72 The letter starts with a reference to the imitation of one’s betters: ‘Since you admire Christ’s holy servants, you have been eager to imitate their piety.’Footnote 73 In the first episode in the letter, as Ammon is introduced to the monastery, the monks are described as gathering around Theodore to ask him to address their ‘faults before them all’. Theodore goes on to refer to Scripture, for instance, Hebrews 11:26 which speaks of Moses, who gladly takes on sufferings for the sake of Christ. Theodore states: ‘But you, why do you bear the reproaches for Christ so grievously?’ Psalms 40:2 is also quoted: ‘He drew me up from the desolate pit, out of the miry bog, and set my feet upon a rock, making my steps secure.’ He addresses the monks’ fear of demons and quotes Ephesians 6:12: ‘for our struggle is not against blood and flesh but against the rulers, against the authorities, against the cosmic powers of this present darkness, against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly places.’ This first passus in The Letter of Ammon, with its strong focus on bearing one’s sufferings with a steady heart, fighting demons and overcoming one’s bodily faults, ends with Theodore’s saying, ‘Guard against your secret [thoughts]’, and paraphrasing Psalms 19:12–13: ‘Pray, saying: “Cleanse me from my hidden [sins], and spare your servant from alien [ideas]”’, to which he adds, ‘For you have a mighty battle on either side.’ The monks are advised to make themselves firm of mind, to be aware of their weaknesses and know their limitations.Footnote 74 So far, The Letter of Ammon and Codex VIII both touch upon many of the same broader themes.

Next, The Letter of Ammon goes on to discuss the hardships that are to come, and to identify the different people who oppose them. Theodore explains that there is a dual threat: from ‘our own race’ and from pagans. He is asked who threatens them from their own race, to which he answers: the Arians. But he also instructs his listeners not to fear this because ‘the persecution by the pagans will end, and then that which presses upon the church from [our own] race will cease’.Footnote 75 This fits the interest the scribe/reader of Codex VIII has highlighted on pages 26, 30 and 45 as well as the passages in The Tripartite Tractate mentioning the psychic race who will be saved in the end even though they are imperfect Christians. There are other passages in The Letter of Ammon which make it clear that there are differences between people. The Pachomian brothers who are weak in faith and fear the consequences of the coming turbulence are described as those who still live in the flesh, or ‘those of the flesh’ (σαρκικοί). However one chooses to interpret the letter, several kinds of difference are mentioned: those within the monastic hierarchy where the lower kinds are likened to the body, as well as with three peoples from a broader anthropological perspective: pagans, erroneous Christians and right practising Christians.

The topic at the centre of the Arian controversy is the theme of several of the passages marked out in Zostrianos, including that on page 64 of Codex VIII which makes it clear that the highest being is a three-powered one. Arians claimed, as is well known, that God and Jesus were not of the same substance, a stance rejected in the sentences marked out by a reader/copyist of Zostrianos.

It must be noted that The Letter of Ammon is written in a context of ecclesiastical struggle and that theological biases might have been embedded in the description of the monastic milieu of a Pachomian monastery.Footnote 76 However, as Hugo Lundhaug has argued, several texts in the Nag Hammadi collection show signs of having been rewritten in light of the new Post-Nicene theological milieu. For example, in The Concept of Our Great Power in Codex VI, a group of neo-Arians called Anomoneans are refuted explicitly by name (40:5–9).Footnote 77 The diplai in Codex I and corone in Codex VIII highlight passages that reflect general Pachomian practices (spiritual warfare) and theological issues from a Post-Nicene context. While the marginal markings made by the readers/owners of the texts do not reflect direct rewritings – which, as Lundhaug argues, is reflected in other parts of the Nag Hammadi collection (a question revisited in Chapter 7) – the marginal markings could be viewed as another example of the way Pachomian monks actually handled the texts in their Post-Nicene context: marking out passages of theological relevance and collecting insights that supported their theological inclinations and broad interests.Footnote 78 The difference in marked-out passages between Zostrianos and The Letter of Peter to Philip concerns theological versus social topics. The marked-out passages in Zostrianos deal with the nature of the godhead, the salvific nature of self-knowledge and the differences among the peoples on earth. The Letter of Peter to Philip contains marked-out passages and sentences dealing with social matters, such as an admonition to preach and not to fear suffering, which is likened to imitating Christ who stepped into the body and suffered for his teachings. In The Tripartite Tractate the marked-out passages highlight general ascetic practices, like engagement in spiritual warfare, but also reflect theological themes associated with Origenism, proclivities also resonating with the interests of Pachomian monks. The proposition that there is evidence of Origenism within both the Pachomian context and the Nag Hammadi codices (a topic revisited in the following chapters) has previously been argued by Lundhaug and Jenott, and recently reiterated by Christian Bull.Footnote 79

Conclusion

The short sentences marked out with diplai and corone in the two codices that have been surveyed in this chapter do not deal with one and the same topic, nor should we expect that. The texts derive from different original contexts and cover a wide array of different subjects. But they all deal with topics that a Christian subject of burgeoning Egyptian monasticism would have found of interest. This is indicated by what we know from monastic sources about such interests, and there is a case to be made that a Pachomian context is a particularly good fit, as indicated by, for example, The Letter of Ammon. I would argue that we would not be hard pressed to imagine that Pachomian monks put in charge of copying the texts of Codex I and VIII made their marks due to their own and their fellow monks’ interests. The fact that other Nag Hammadi texts, as we shall see later, were most likely rewritten in the light of the new theological situations arising in the middle of the fourth century supports this reading. As the marginal markings reflect the interests of Pachomian monks, they could be viewed as one way in which Pachomian monastic readers actually used the texts: as reference, inspiration and support in traversing the theologically debated topics of the latter part of the fourth century.

In the remaining chapters, as we continue to survey uncharted perspectives of the material aspects of the Nag Hammadi codices, the practical use of the texts within a monastic setting in Upper Egypt during the fourth to fifth centuries are further elaborated. With regard to the use of diplai and corone in monastic textual communities, there remains much to be done and the present discussion should be seen as only a preliminary and modest attempt to pave the way for further studies.Footnote 80