Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Note on conventions

- Introduction

- 1 Pre-history: how Western music came to Japan

- 2 Music and ‘pre-music’: Takemitsu's early years

- 3 Experimental workshop: the years of Jikken Kōbō

- 4 The Requiem and its reception

- 5 Projections on to a Western mirror

- 6 ‘Cage shock’ and after

- 7 Projections on to an Eastern mirror

- 8 Modernist apogee: the early 1970s

- 9 Descent into the pentagonal garden

- 10 Towards the sea of tonality: the works of the 1980s

- 11 Beyond the far calls: the final years

- 12 Swimming in the ocean that has no West or East

- Notes

- List of Takemitsu's Works

- Select bibliography

- Index

5 - Projections on to a Western mirror

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 18 August 2009

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Note on conventions

- Introduction

- 1 Pre-history: how Western music came to Japan

- 2 Music and ‘pre-music’: Takemitsu's early years

- 3 Experimental workshop: the years of Jikken Kōbō

- 4 The Requiem and its reception

- 5 Projections on to a Western mirror

- 6 ‘Cage shock’ and after

- 7 Projections on to an Eastern mirror

- 8 Modernist apogee: the early 1970s

- 9 Descent into the pentagonal garden

- 10 Towards the sea of tonality: the works of the 1980s

- 11 Beyond the far calls: the final years

- 12 Swimming in the ocean that has no West or East

- Notes

- List of Takemitsu's Works

- Select bibliography

- Index

Summary

Takemitsu's theoretical writings about music abound in striking metaphors that have proved a fertile resource for commentators in search of an evocative title or handy descriptive phrase. The present writer is no exception to this general rule: the title of this chapter, for instance, is a reference to Takemitsu's famous essay of 1974, ‘Mirror of Tree, Mirror of Grass’, in which he compares Western music, with its emphasis on the individual, to the tree, and contrasts this with non-Western musics which have ‘grown like grass’. The two mirrors thus symbolise the twin musical cultures into which Takemitsu was to ‘project himself’ as his musical language developed, and – as he makes explicit – for the first part of his life it was into the ‘Western’ mirror only that his gaze was directed: ‘Once, I believed that to make music was to project myself on to an enormous mirror that was called the West.’

Our examination of Takemitsu's career to date has corroborated the truth of this assertion. With one or two significant exceptions, most of his musical preoccupations have derived from the Western tradition, and one can generally agree with Poirier that the young Takemitsu devoted himself completely to this ‘music from elsewhere’ while ‘abandoning completely the heritage of traditional music’. Very soon things were to change dramatically, but this does not mean that Takemitsu abandoned his continued exploration of the ‘Western’ mirror.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

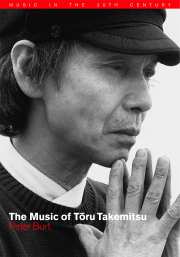

- The Music of Toru Takemitsu , pp. 73 - 91Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2001