Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Music, Indigeneity, Digital Media: An Introduction

- 1 Taiwan's Aboriginal Music on the Internet

- 2 Recording Technology, Traditioning, and Urban American Indian Powwow Performance

- 3 YouTubing the “Other”: Lima's Upper Classes and Andean Imaginaries

- 4 An Interview with Russell Wallace

- 5 Mixing It Up: A Comparative Approach to Sámi Audio Production

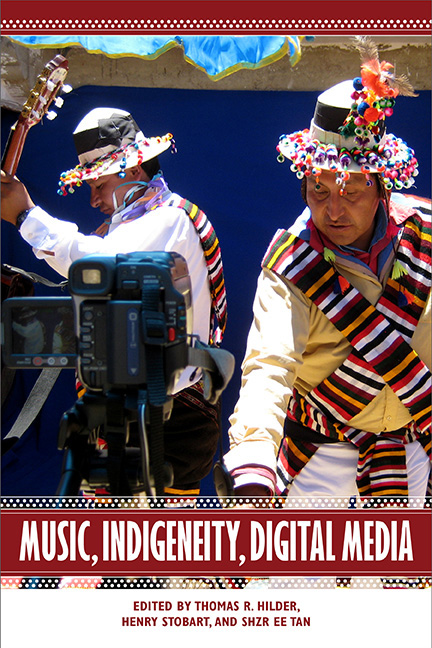

- 6 Creative Pragmatism: Competency and Aesthetics in Bolivian Indigenous Music Video (VCD) Production

- 7 Keepsakes and Surrogates: Hijacking Music Technology at Wadeye (Northwest Australia)

- 8 The Politics of Virtuality: Sámi Cultural Simulation through Digital Musical Media

- Selected Bibliography

- List of Contributors

- Index

1 - Taiwan's Aboriginal Music on the Internet

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 26 April 2018

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Music, Indigeneity, Digital Media: An Introduction

- 1 Taiwan's Aboriginal Music on the Internet

- 2 Recording Technology, Traditioning, and Urban American Indian Powwow Performance

- 3 YouTubing the “Other”: Lima's Upper Classes and Andean Imaginaries

- 4 An Interview with Russell Wallace

- 5 Mixing It Up: A Comparative Approach to Sámi Audio Production

- 6 Creative Pragmatism: Competency and Aesthetics in Bolivian Indigenous Music Video (VCD) Production

- 7 Keepsakes and Surrogates: Hijacking Music Technology at Wadeye (Northwest Australia)

- 8 The Politics of Virtuality: Sámi Cultural Simulation through Digital Musical Media

- Selected Bibliography

- List of Contributors

- Index

Summary

More than a decade since the settling of a controversial lawsuit involving pop group Enigma's use of Amis song in the 1993 hit “Return To Innocence,” aboriginal musicians in Taiwan are grappling with new ideas about mediation, self-representation, cultural ownership, and musical stewardship. Emerging issues in today's diversified networks of music production and consumption extend beyond old debates about copyright; a newer line of inquiry traces the interacting pathways old and new media platforms have carved out in recent years. This article examines how regionally oriented rural routes established through cassette cultures of the 1980s, still prevalent, are being tapped into by more modern (and superficially “urban”) channels of CD distribution. Internet and mobile technology have also remapped old configurations of cultural flow. This is observable not only in the development of parallel online and offline musical communities but also in the widening, global reach of music-interfaced aboriginal transnationalism. At the same time, these routes have also paved the way for emerging cultural disjunctures. In particular, I investigate how the digital divide can be articulated not as a “Han-vs.-aboriginal” or even a “rural-vs.-urban” pattern, but as a generation gap. I study how this gap is itself bridged through mediated musical practices that integrate live and physical dimensions. I look at how feedback between new and existing communities impacts aboriginal musical ecosystems, and study how cultural identities are deliberately or incidentally represented.

The sections to follow first challenge the idea of “newness” in new media, reexamining old tropes of recontextualization understood through differentiated aboriginal experiences of twenty-first century digitality. Here, unequal access to digital resources, information, and power privilege as well as disadvantage intersecting categories of cultural insiders and outsiders and the technologically savvy. Often, the digital quest for a musical connection requires the querent to know exactly what he or she is looking for, even before multiple hidden pathways to the holy grail can show themselves: thus, even slight alterations of Internet music video search parameters lead to dramatically different results. Next, I study how specific parties—from national institutions to commercial players, from local communities to cyberactivists—hold different digital stakes in the game of information representation and music exchange.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Music, Indigeneity, Digital Media , pp. 28 - 52Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2017