Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Music, Indigeneity, Digital Media: An Introduction

- 1 Taiwan's Aboriginal Music on the Internet

- 2 Recording Technology, Traditioning, and Urban American Indian Powwow Performance

- 3 YouTubing the “Other”: Lima's Upper Classes and Andean Imaginaries

- 4 An Interview with Russell Wallace

- 5 Mixing It Up: A Comparative Approach to Sámi Audio Production

- 6 Creative Pragmatism: Competency and Aesthetics in Bolivian Indigenous Music Video (VCD) Production

- 7 Keepsakes and Surrogates: Hijacking Music Technology at Wadeye (Northwest Australia)

- 8 The Politics of Virtuality: Sámi Cultural Simulation through Digital Musical Media

- Selected Bibliography

- List of Contributors

- Index

8 - The Politics of Virtuality: Sámi Cultural Simulation through Digital Musical Media

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 26 April 2018

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Music, Indigeneity, Digital Media: An Introduction

- 1 Taiwan's Aboriginal Music on the Internet

- 2 Recording Technology, Traditioning, and Urban American Indian Powwow Performance

- 3 YouTubing the “Other”: Lima's Upper Classes and Andean Imaginaries

- 4 An Interview with Russell Wallace

- 5 Mixing It Up: A Comparative Approach to Sámi Audio Production

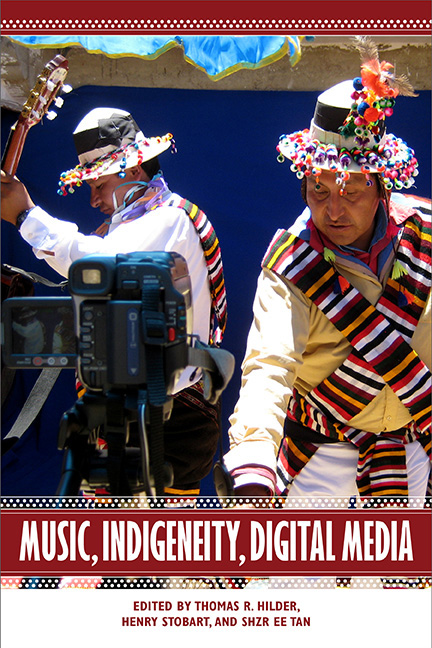

- 6 Creative Pragmatism: Competency and Aesthetics in Bolivian Indigenous Music Video (VCD) Production

- 7 Keepsakes and Surrogates: Hijacking Music Technology at Wadeye (Northwest Australia)

- 8 The Politics of Virtuality: Sámi Cultural Simulation through Digital Musical Media

- Selected Bibliography

- List of Contributors

- Index

Summary

The virtual is something that is almost, but not quite, “real,” as Rob Shields writes in his study of virtuality. Etymologically related to the term virtue, he elucidates, it has in various cultural and historical contexts been linked to dreams, rituals, and the visual arts. In the digital era, virtuality has come to be associated almost exclusively with online communities and simulating technologies. Today, virtuality is often considered negatively, as a form of escapism that deceives and deludes, amplified by a larger trope of the apparent alienating, antihuman, dystopian facets of technology. This sentiment has most famously been articulated by Jean Baudrillard, who writes in Simulacra and Simulation that we have entered the age of “simulacra,” a “hyperreal order” in which the perceived world is simply a vast assemblage of simulations that obscure deeper political and social realities. However, contemporary anxieties about simulation are part of a longer history of a disdain for the “virtual,” fueled by the legacy of Enlightenment thought, colonial practice, and nineteenth-century empiricism, fixated on the observable, tangible, and measurable world.

Baudrillard's theory itself rests upon a problematic notion of Indigenous people as passive victims of a world obsessed with the authentic and “real” and denies the possibility of Indigenous people adopting media technologies for their own cultural and political purposes. Moreover, it overlooks how notions of realms beyond the visible human world are common within many cultures, including numerous Indigenous cosmologies. Following the literature of virtuality, this chapter takes issue with Baudrillard's Simulacra and Simulation by exploring how digitally assisted cultural simulation can enable powerful means of Indigenous cultural revival, musical transmission, and political articulation. I focus on the Sami, the Indigenous people of Northern Europe, and investigate how digital technology—in museums, educational software, and CD production— has become part of the complex and dynamic fabric of Indigenous cultures, in turn transforming notions of Indigenous subjectivity, cultural belonging, and political activism. In particular, I inspect how digital cultural simulation can help to revive a Sami Indigenous cosmology, within which the human world exists alongside the realms of the spirits and the dead. How do Indigenous artists and activists resist notions of a world subsumed by the “hyperreal order”?

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Music, Indigeneity, Digital Media , pp. 176 - 204Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2017