Book contents

- Modern Erasures

- Modern Erasures

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures and Maps

- Acknowledgments

- Note on the Text

- Introduction

- Part I Seeing and Not Seeing

- Part II Revolutionary Memory in Republican China

- Part III Maoist Narratives in the Forties

- Part IV Politics of Oblivion in the People’s Republic

- Conclusion

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

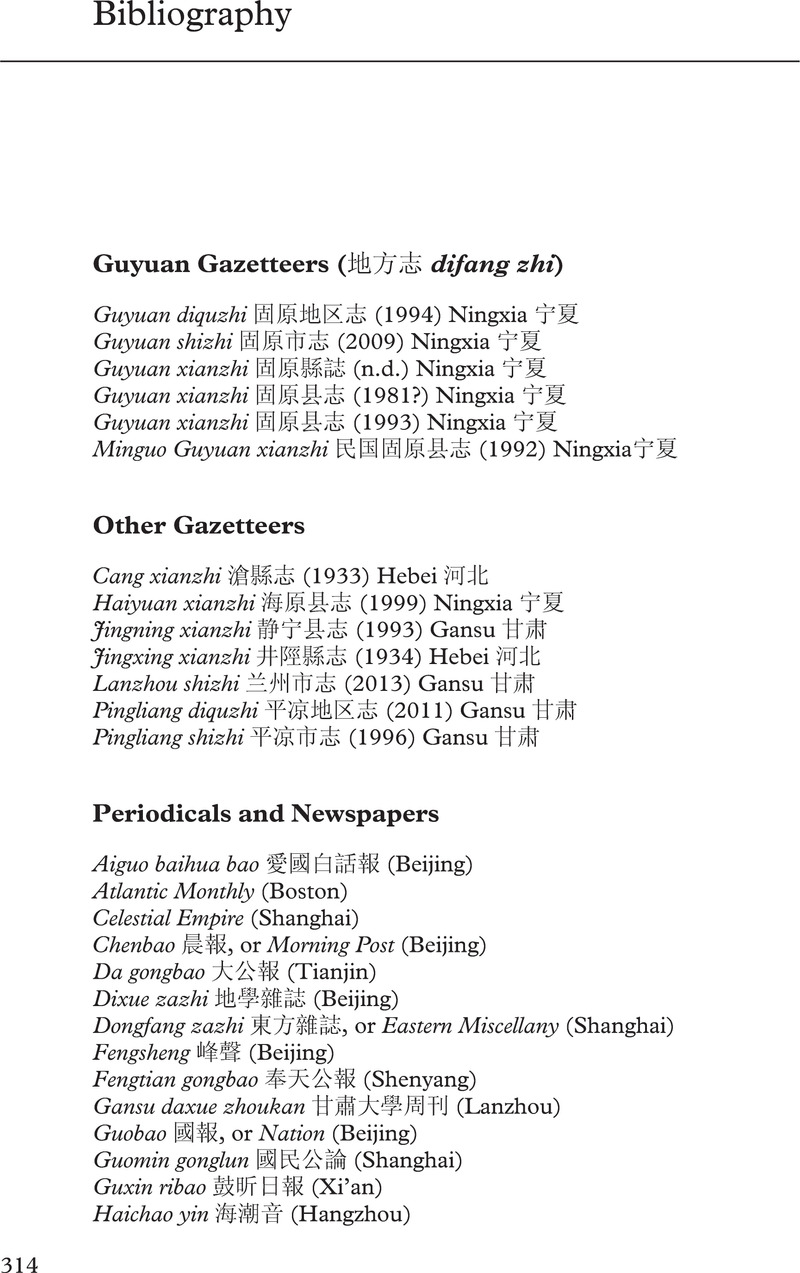

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 31 March 2022

- Modern Erasures

- Modern Erasures

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures and Maps

- Acknowledgments

- Note on the Text

- Introduction

- Part I Seeing and Not Seeing

- Part II Revolutionary Memory in Republican China

- Part III Maoist Narratives in the Forties

- Part IV Politics of Oblivion in the People’s Republic

- Conclusion

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Modern ErasuresRevolution, the Civilizing Mission, and the Shaping of China's Past, pp. 314 - 335Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2022