Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- List of Images

- An Introduction

- 1 Wound: On Caravaggio’s Martyrdom of Saint Ursula

- 2 Touch: On Giovanni Lanfranco’s Saint Peter Healing Saint Agatha

- 3 Skin: On Jusepe de Ribera’s Martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew

- 4 Flesh: On Georges de La Tour’s Penitent Saint Jerome

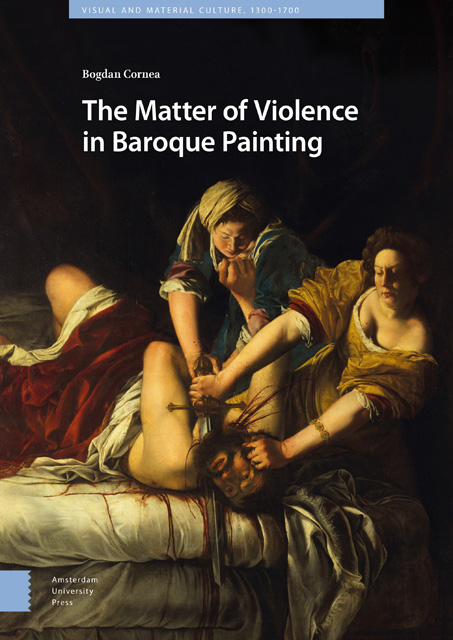

- 5 Blood: On Artemisia Gentileschi’s Judith Slaying Holofernes

- 6 Death: On Francisco de Zurbarán’s The Martyrdom of Saint Serapion

- Conclusion

- General Bibliography

- Index

1 - Wound: On Caravaggio’s Martyrdom of Saint Ursula

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 18 April 2023

- Frontmatter

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- List of Images

- An Introduction

- 1 Wound: On Caravaggio’s Martyrdom of Saint Ursula

- 2 Touch: On Giovanni Lanfranco’s Saint Peter Healing Saint Agatha

- 3 Skin: On Jusepe de Ribera’s Martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew

- 4 Flesh: On Georges de La Tour’s Penitent Saint Jerome

- 5 Blood: On Artemisia Gentileschi’s Judith Slaying Holofernes

- 6 Death: On Francisco de Zurbarán’s The Martyrdom of Saint Serapion

- Conclusion

- General Bibliography

- Index

Summary

Abstract

Chapter One examines Caravaggio’s Martyrdom of Saint Ursula by focusing on the peculiar staging of the wound and its relation to the radical transformation of her body. By interrogating Caravaggio’s manipulation of time and pictorial narrative, the chapter emphasizes the fragmentation at play within the painting to draw an ontological distinction between the figure of the saint and the rest of the depicted figures. The chapter argues that the hidden violence of the wound sets forth a process of corporeal becoming that transforms the figure of the saint into an icon – a distinct sacred image of a living martyr that has already departed the world of the living to become an other-worldly image of divine redemption.

Keywords: Caravaggio, wound, narrative, fragmentation, becoming, holiness

When a thing is hidden away with so much pain, merely to reveal it is to destroy it.

– TertullianThe bow is shot, the hands are lowered, the arrow transfixed into the body of the saint. Her countenance displays little emotion. With a slight furrow of the brow, she gazes down into the entry of her body. Gushes of blood flow in distinct yet dazzling drops that do little to stir any sign of distress or sorrow on her countenance; her face remains rigid, her gaze trapped in an unsettling pose of curiosity. Saint Ursula seems to linger on her wound with unnatural poise. Under the stunned gazes of the other participants, her wound becomes fertile; it overflows with blood and life. This phenomenon achieves a radical effect on her body. She is pale white, as if already drained of life; her body is brittle and evanescent – the concrete materiality of her flesh is shown to undergo a significant change; something akin to a miraculous act of transformation.

Caravaggio’s Martyrdom of Saint Ursula (1610) (Image 2) invites viewers to dwell and linger on the effects of the wound. For everything revolves around it: the saint, the soldiers, and the king, they all seem absorbed by the entry in her body. With her hands held high, the saint frames the spot as a moment of intense obscurity – a pictorial fragment from where we see the bleeding, we see the arrow in her chest; and yet, despite all our the expectations, we cannot see the laceration in her flesh.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Matter of Violence in Baroque Painting , pp. 29 - 52Publisher: Amsterdam University PressPrint publication year: 2023