Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- List of Images

- An Introduction

- 1 Wound: On Caravaggio’s Martyrdom of Saint Ursula

- 2 Touch: On Giovanni Lanfranco’s Saint Peter Healing Saint Agatha

- 3 Skin: On Jusepe de Ribera’s Martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew

- 4 Flesh: On Georges de La Tour’s Penitent Saint Jerome

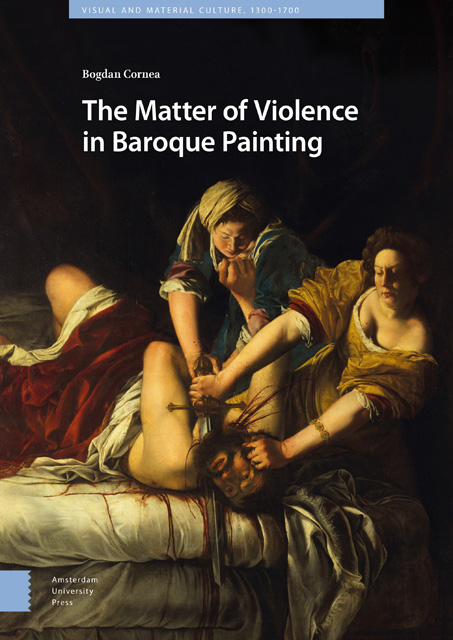

- 5 Blood: On Artemisia Gentileschi’s Judith Slaying Holofernes

- 6 Death: On Francisco de Zurbarán’s The Martyrdom of Saint Serapion

- Conclusion

- General Bibliography

- Index

- Frontmatter

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- List of Images

- An Introduction

- 1 Wound: On Caravaggio’s Martyrdom of Saint Ursula

- 2 Touch: On Giovanni Lanfranco’s Saint Peter Healing Saint Agatha

- 3 Skin: On Jusepe de Ribera’s Martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew

- 4 Flesh: On Georges de La Tour’s Penitent Saint Jerome

- 5 Blood: On Artemisia Gentileschi’s Judith Slaying Holofernes

- 6 Death: On Francisco de Zurbarán’s The Martyrdom of Saint Serapion

- Conclusion

- General Bibliography

- Index

Summary

Baroque depictions of violence display an excess of material richness and visual complexity that engage viewers in new forms of corporeal and visceral relations. This book has traced a path that avoids the prevailing interpretation of paintings as mere reflections of the supposedly violent nature of seventeenth-century society; instead, it explores them as active presences or intensities capable of producing unforeseen and untameable set of engagements. The power of these paintings is shown to emerge from a violence that erupts from within the materiality of the painting that works at times in alignment but most often in disjunction with the subject of representation. As such, the violence mostly observed is not one that can be reduced to a simple depiction of a beheading of flaying, but exceeds any system of closure demanded by representation; thus the excessive work of materiality is shown to be transgressive, disruptive, and transformative – enacting a violent event of becoming.

The first two chapters explored the paradox of staging a painting around the violent opening of a wound. The first chapter showed how Caravaggio’s Martyrdom of Saint Ursula (1610) is built around the focal point of the wound – the saint, the soldiers, and the king – all figures absorbed by its presence. The wound, however, is hidden from sight. The obstruction of sight as a means of refocusing and bringing into play other forms of corporeal engagement was further investigated in the second chapter on Giovanni Lanfranco’s Saint Peter Healing Saint Agatha (1613–1614). We have seen how in both paintings, the place of the wound can become, in distinct ways, a pictorial moment of miraculous transformation where the sacred intervenes violently within matter. Both chapters have explored the various disruptions and dislocations – temporal, figurative, and narrative – that are set into motion in order to transform the saintly figures of Ursula and Agatha into distinct sacred images within an image. This process of dislocation challenges sight and touch as primary modes of artistic engagement. For if Caravaggio concealed the wound from visibility – and hence made invisible the blinding power of the sacred made material – Lanfranco opened the question of touching as a contact at the limit of the sacred image.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Matter of Violence in Baroque Painting , pp. 161 - 164Publisher: Amsterdam University PressPrint publication year: 2023