Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- List of Images

- An Introduction

- 1 Wound: On Caravaggio’s Martyrdom of Saint Ursula

- 2 Touch: On Giovanni Lanfranco’s Saint Peter Healing Saint Agatha

- 3 Skin: On Jusepe de Ribera’s Martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew

- 4 Flesh: On Georges de La Tour’s Penitent Saint Jerome

- 5 Blood: On Artemisia Gentileschi’s Judith Slaying Holofernes

- 6 Death: On Francisco de Zurbarán’s The Martyrdom of Saint Serapion

- Conclusion

- General Bibliography

- Index

5 - Blood: On Artemisia Gentileschi’s Judith Slaying Holofernes

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 18 April 2023

- Frontmatter

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- List of Images

- An Introduction

- 1 Wound: On Caravaggio’s Martyrdom of Saint Ursula

- 2 Touch: On Giovanni Lanfranco’s Saint Peter Healing Saint Agatha

- 3 Skin: On Jusepe de Ribera’s Martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew

- 4 Flesh: On Georges de La Tour’s Penitent Saint Jerome

- 5 Blood: On Artemisia Gentileschi’s Judith Slaying Holofernes

- 6 Death: On Francisco de Zurbarán’s The Martyrdom of Saint Serapion

- Conclusion

- General Bibliography

- Index

Summary

Abstract

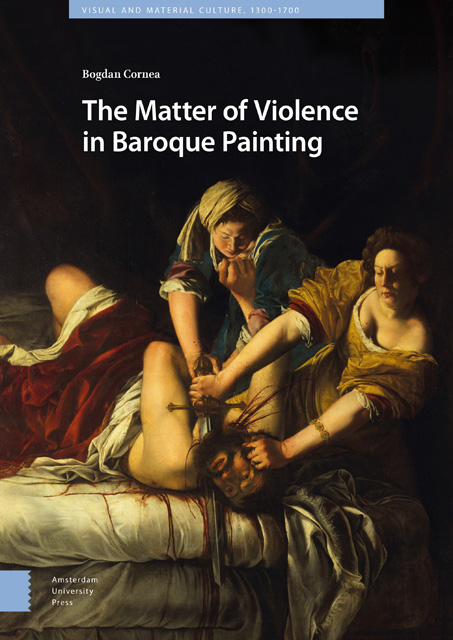

Chapter Five addresses the excess of blood and the creation of violence in Artemisia Gentileschi’s Judith Slaying Holofernes. By drawing a distinction in the depiction of blood – the blood that flows from the neck and the drops on the surface – this chapter argues that Gentileschi staged the painting into a surface of violence. By engaging extensively with primary sources, the chapter analyses the paradoxical coupling of horror and delight, relating it with the notion of abjection and its potential to transform the painting into a liminal surface of violence. The chapter argues that Judith’s handling of the sword slices away not only the head of Holofernes, but also performs an act of transformation, where the pictorial surface, through the materiality of the blood, becomes a liminal space of abjection and violence.

Keywords: Artemisia Gentileschi, blood, surfaces, horror, delight, cut

I see thee still;

And on thy blade and dudgeon gouts of blood,

Which was not so before. There’s no such thing:

It is the bloody business, which informs

Thus to mine eyes.

– William ShakespeareBlood stands out – a life-giving substance overflowing and overwhelming. Blood compels; it holds our gaze in repulsive fascination. We are astonished by its abundance; it spouts violently from the neck in mid-air, poring over the white sheets; lingering in crisp creases and fabrics. We are repulsed yet we cannot look away. Blood wields its power to produce an abject coupling of horror and delight. In Artemisia Gentileschi’s Judith Slaying Holofernes (1614–1629) (Image 16), blood stages the painting as a liminal space of abjection. Its presence demands distinction – there is the blood that streams from the general’s neck in jets of unbounded energy and the drops that drip and hover over the surface of the canvas, as if the artist delivered a violent splash, a sudden stroke of the fully loaded brush, and spread its content on the surface of the canvas.

These small drops are different in substance and form from the violent gushes that stream from the severed head. They proclaim their presence as something that belongs to the surface of the painting, yet is set apart and made distinct from the rest of the unfolding drama. Each drop enacts difference within similitude.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Matter of Violence in Baroque Painting , pp. 119 - 140Publisher: Amsterdam University PressPrint publication year: 2023