Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- List of Images

- An Introduction

- 1 Wound: On Caravaggio’s Martyrdom of Saint Ursula

- 2 Touch: On Giovanni Lanfranco’s Saint Peter Healing Saint Agatha

- 3 Skin: On Jusepe de Ribera’s Martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew

- 4 Flesh: On Georges de La Tour’s Penitent Saint Jerome

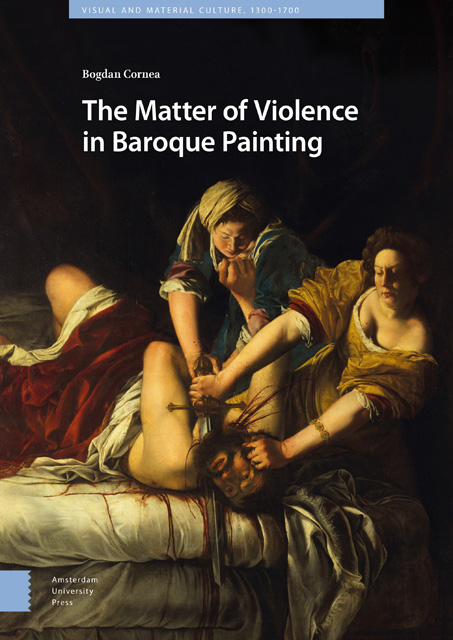

- 5 Blood: On Artemisia Gentileschi’s Judith Slaying Holofernes

- 6 Death: On Francisco de Zurbarán’s The Martyrdom of Saint Serapion

- Conclusion

- General Bibliography

- Index

- Frontmatter

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- List of Images

- An Introduction

- 1 Wound: On Caravaggio’s Martyrdom of Saint Ursula

- 2 Touch: On Giovanni Lanfranco’s Saint Peter Healing Saint Agatha

- 3 Skin: On Jusepe de Ribera’s Martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew

- 4 Flesh: On Georges de La Tour’s Penitent Saint Jerome

- 5 Blood: On Artemisia Gentileschi’s Judith Slaying Holofernes

- 6 Death: On Francisco de Zurbarán’s The Martyrdom of Saint Serapion

- Conclusion

- General Bibliography

- Index

Summary

Abstract

This introductory chapter maps the relation between violence, baroque painting, and materiality and sets forth the outlines and aims of the book. Materiality is taken as a central feature in the understanding of the art object – in particular, as a key factor in the production of violence by dislocating time, fragmenting surfaces, and transgressing representation. This approach emphasizes art’s ability to become, to be generative and transformative. The transformational and generative potential of art is best exemplified in its propensity for excess – understood here as baroque’s operative function. The relationship between violence and transformation is brought into focus in my interpretation of paintings as corporeal surfaces, meant to confront beholders with new and radical forms of violence.

Keywords: baroque, violence, materiality, excess, corporeality, phenomenology

For nothing was simply one thing.

– Virginia WoolfA Work of Dissemblance, Most Difficult to Tell. It begins with a detail. The artist: Jusepe de Ribera; the painting: Apollo Flaying Marsyas (Image 1). At the centre of the canvas – a great billowing cloak, twisting and turning around the body of the young god. Apollo stands proudly and detached, his hand plunged deep within the body of the satyr, his fingers separating skin from living flesh. The satyr is shown tied to a tree trunk; his bearded face hangs low into the foreground, his mouth opened in a deafening scream of silence. The entire canvas succumbs to a tension of stretch flesh, smiling and failing, worn out at the edge – open mouth to open skin – there, before us.

The cloak swirls around the pristine body of the ancient god like a protective metallic armour. Its subtle variations of reds and pinks are occasionally intermingled with thin threads of white paint, all applied in swift touches of the brush; from this, a complex material relationship emerges that gives the surface its haptic quality: frothy and moist, fluid and tender like the open tissue of living flesh. The lower edge of Apollo’s cloak falls into close proximity with Marsyas’s wound. One can see it as a critical moment of confrontation, for the cloak and the wound draw towards each other, only to highlight the difference between the two. If the wound renders a correct anatomical interior – polished and detached – the materiality of the cloak achieves the potentiality of a trembling tissue of openly flayed skin.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Matter of Violence in Baroque Painting , pp. 13 - 28Publisher: Amsterdam University PressPrint publication year: 2023