The British geographer, botanist and ethnographer Clements Robert Markham's memoir detailing the transportation of cinchona seeds and plants from South America to South India, one might recall, was published in 1862. A few years after the Sepoy Mutiny, which marked the transition from East India Company rule to the British Raj, Markham argued that trees planted by rulers were the most enduring legacies of imperial regimes, comparing the recently imported cinchona plants in British India with the melon trees planted by Emperor Babur, the founder of the Mughal dynasty. He envisioned that these cinchona plants, much like Babur's melons, would outlast not only spectacular political events and engineering marvels, but also withstand the rise and fall of empires themselves. These plants, he thought, should be considered an everlasting gift to Her Majesty's Indian subjects from their imperial rulers.Footnote 1

Cinchona plants and their most valuable extract, quinine, continued to remain significant in commerce, public health and global politics in the interwar periodFootnote 2. Across South Asia, as the last chapter has shown, the interrelationships amongst cinchona plants, the drug quinine, the tropical disease malaria and anopheles mosquitoes were already widely recognised by the start of World War I. However, the first two decades of the twentieth century also witnessed the beginnings of widespread disillusionment with imperial cinchona plantations and government quinine factories in British India. Insofar as cinchona plantations were concerned, the superiority of Dutch Java was almost entirely established by then.Footnote 3 Private planters in northeastern India and Ceylon, as I have indicated, began replacing cinchonas from their plantations with other commercial crops. Books published from other parts of the Empire in the 1910s ironically claimed that cinchonas were not only frequently vulnerable to different diseases, but they were also sources of occupational skin diseases amongst those who handled these plants while ‘making pharmaceutical preparations’.Footnote 4 The effectiveness of quinine itself was questioned amidst allegations of extensive adulteration in the medical markets, poisonous side effects, the emergence of cheaper pharmaceutical alternatives and the suggestion that eradicating mosquitoes was a more efficient way of resisting malaria than quinine prophylaxis.Footnote 5 Many of these limitations of quinine were highlighted in debates between colonial medical officials regarding the most effective ways of controlling malaria in the 1900s and 1910s. These debates were conducted in a range of imperial political contexts including colonial public health campaigns, everyday municipal governance, or in spectacular military frontiers during the World War I.Footnote 6 The recognition of quinine as an anti-malarial survived these debates, and yet the effectiveness of the drug was subjected to unprecedented scrutiny during these years.

In concluding this book, I want to offer three distinctive analytical perspectives. The first draws together the threads of the argument in the preceding chapters, demonstrating that British imperial agency not only shaped the histories of quinine and malaria, but also occasioned the interactions between these categories. The second section of the epilogue reasserts the significance of non-European vernacular public culture in the history of British imperial medicine. I explore Bengali writings on malaria, quinine and mosquitoes in some detail to suggest ways to go beyond the twin tropes of imposition and resistance in the history of British imperial medicine. The final section will focus on nonhuman objects and organisms to critique anthropocentrism in standard historiography of British Empire. Taken together these two sections extend existing conceptions of British imperial agency by focusing on interactive relationships between the British Empire and different components within imperial history. I will argue that the focus on imperial agency in this book does not imply the methodological marginalisation of either vernacular public cultures or nonhumans. Instead, I conclude by suggesting that various vernacular public cultures and nonhumans were not only co-constituted with British imperial history, but also were integral to it.

A Cure and Its Disease

Although I began this book with an analysis of the discovery of the alkaloid quinine in 1820, I have focused especially on the period between Markham's programmatic statements in the early 1860s (marking the establishment of cinchona plantations in British India) and the beginning of systematic doubts about the effectiveness of quinine in the late 1900s and early 1910s. In these intervening decades, British India was one of most significant parts of the colonial world where quinine was established as the quintessential cure for diseases associated with malaria. Rather than proposing a self-contained history of malaria or quinine, I have explored the ways in which the historical trajectories of a disease, a cure, a group of plants and (subsequently) insects intersected. While examining the interconnected histories of quinine and malaria during this period, I have questioned the conventional chronologies of medical knowledge production. Such established chronologies have often assumed a definite pattern according to which: problems inevitably precede a solution, an answer takes shape only after a coherent question has been posed, and preexisting understandings about a disease necessitate knowledge about a cure. Instead, this book has argued that knowledge about a cure and a disease-causing entity, to a considerable extent, shaped one another. In fact, it is not entirely implausible to think about situations in which knowledge about cinchona and quinine preceded, and effected crucial shifts in the history of malaria. Chapters 1 and 2 indicate that the establishment of colonial cinchona plantations in Dutch Java, French Algeria and British India in the mid-nineteenth century converged with the redefinition of malaria from a predominantly European to an almost exclusively colonial concern. While the word malaria certainly had a presence in English language sources in the previous centuries, the discovery of quinine in 1820 was followed by unprecedented circulation of malaria as a diagnostic category and as a matter of governmental preoccupation. Chapter 3 has shown, while commenting on the making of Burdwan fever, that quinine could be invoked to establish the malarial identity of a malady. In many instances during the epidemic, confirmed diagnoses did not lead to the prescription of cure. On the contrary, quinine was employed as a pharmacological agent in quick-fix diagnostic tests. Thus the malarial identity of a malady was ascertained by the response of the ailing body to quinine.

At the same time, the incorruptibility and inflexibility of the pharmaceutical category quinine itself was not necessarily taken for granted by contemporary officials. Therefore, British colonial bureaucrats, who assumed that the Burdwan fever assured the supply of bodies affected with malaria, used the ‘opportunity of the epidemic’, in turn, to verify the ‘purity’ of certain drugs circulating extensively as quinine in the medical market. Focusing on attempts to manufacture pure quinine in government factories in British India, Chapter 4 has further explored the irony that despite being employed to establish whether an ailing body was suffering from malaria, quinine itself remained an unstable, malleable as well as elusive entity over many decades. Quinine continued being described as a quintessential remedy in the early 1900s, as has been shown in the previous chapter, even when the corresponding diagnostic category malaria itself was redefined substantially: from an elusive cause of many diseases to the name of a mosquito-borne fever disease. In this decade, prevailing insights about how quinine cured an ailing body were altered to adapt to the newer meanings associated with the category malaria.

I have contributed to attempts within the wider historiography of science to demystify expressions such as experiments, discovery and invention. While narrating the history of quinine manufacture in British India, for example, I have urged that these expressions should not only be read as indicators of the teleological development of pharmaceutical technology, but also as politically contingent, historically produced labels. Similarly, I have indicated that the chemical separation of two newer alkaloids from extracts of cinchona barks was not termed as an exceptional discovery in the world of phytochemistry in 1820 itself. The accomplishment of Pelletier and Caventou was retrospectively glorified as a momentous event in the history of pharmaceutical chemistry because of the recognition quinine eventually received from the market in subsequent decades. Likewise, the mosquito brigades organised in the 1900s were not applications to the ‘field’ of an already established discovery achieved within the walls of enclosed laboratories. Instead, such elaborate ‘expeditions’ emerged as occasions for reconfirming tentative laboratory findings, and reasserting them before a global audience. This book, therefore, reinforces persisting efforts to recast the histories of scientific milestones, while at the same time questioning the established chronologies in the relationships between a disease and its cure. In the process, it contradicts the suggestion that modern medicine necessarily represents an objective, teleological and progressive uncovering of scientific reason.

The mutual co-constitution of the drug quinine and the disease malaria was shaped, to a great extent, by the histories of British Empire in the long nineteenth century. In concluding in the late 1900s and early 1910s, I have situated the crystallisation of interrelationships amongst malaria, quinine and mosquitoes within wider trends of the links between natural knowledge and modern imperial rule. As in the case of malaria, other scholars have shown, various developments in the early twentieth century in the fields of natural knowledge and practice, particularly in bacteriology, anthropology and ecology were culminations of processes that had their roots in the imperial history of the nineteenth century.Footnote 7 Indeed, the consolidation of natural knowledge about cinchonas, malaria, quinine, and mosquitoes, and the establishment of interrelationships between them were not inevitable or accidental, but rather the exigencies and apparatuses of imperial rule shaped them. The British Empire occasioned not only the imbrications of the worlds of medical knowledge, pharmaceutical commerce, colonial governance and (as I will elaborate further in the next section) vernacular public cultures, but also bound South Asian history with events unfolding in distant parts of the world, particularly in South America, the West Indies, German, French and British Africa, and Dutch Java. While analysing the persistence of malaria as a diagnostic category, I have focused on the nineteenth century in its own right. I have refused to treat it as a period characterised by flawed archaic understandings about the disease which would be rectified eventually in course of the next century.

Malaria, of course, continued to remain a significant concern in world history and politics in the interwar period. Many recent books on the history of malaria have focused predominantly on the twentieth century.Footnote 8 This book has provided a historical backdrop to the period covered by these existing scholarly works by identifying the ways in which malaria was reconfigured as a major concern for global governance in the imperial context of the long nineteenth century. This context also shaped the interactions between the scholarly disciplines of tropical medicine, parasitology and entomology, and these interactions in turn, resulted in the preponderance of narratives about blood, parasites and mosquitoes in the literature concerning malaria in the early twentieth century.

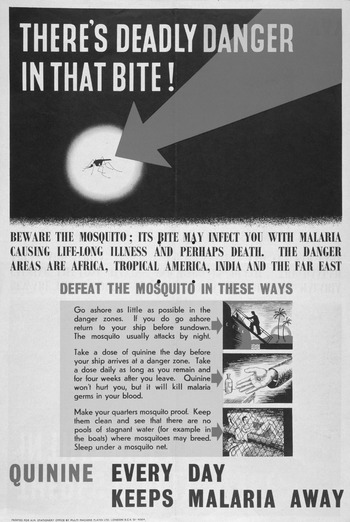

By focusing on this period, this book reveals how certain nineteenth-century trends in the history of malaria persisted into the next century. Events in the early decades of the twentieth century, particularly the redefinition of malaria as a mosquito-borne, parasite-caused fever disease and the discrediting of quinine did not immediately constitute an incommensurable epistemological break in the history of malaria and its cures. Indeed, as I have indicated in Chapter 5, in various quarters, practices such as the therapeutic prescription of quinine, the use of drugs such as quinine for clinical diagnosis of malaria, and the projection of malaria as a commodious cause of many maladies did not entirely cease.Footnote 9 One of the lasting legacies of the nineteenth-century literature about malaria was the continued association of the category predominantly with colonial and postcolonial landscapes. Undoubtedly, malaria reemerged as a prominent concern that afflicted various parts of Europe, extending beyond ‘the semicolonial appendage’ of southern Italy in the late nineteenth and the early twentieth centuries.Footnote 10 However, before long, malariologists celebrated the ‘disappearance’ of malaria from various parts of the United States and Europe, particularly, England.Footnote 11 It was argued that the ‘disappearance’ of malaria could be attributed to ‘civilising social influences’ and ‘scientific agriculture’ that were in vogue in these parts of the world.Footnote 12 Published in 1946, A Malariologist in Many Lands, a scientific memoir written by Marshall A, Barber, a public health professional associated with the Rockefeller Foundation amongst other organisations, did not devote any of the chapters to Western Europe or even Italy.Footnote 13 A reviewer of this account took note of Barber's claim that ‘decrease (of malaria) in the United States is almost universal’ and that ‘an analogous decrease in malaria has occurred in northern and central Europe’.Footnote 14 Instead, the memoir focused predominantly on various corners of the colonial and postcolonial world such as parts of Central America, the West Indies, the Philippine Islands, Malaya and the Fiji islands, Equatorial Africa, Egypt, India and Brazil. A twentieth-century poster (Figure 6.1) which was released in London by Her Majesty's Stationary Office as an instruction for travellers identified the vast expanses of the colonial and postcolonial world including ‘Africa, Tropical America, India and the Far East’ as the ‘danger areas’ for acquiring malaria, and recommended everyday use of quinine and mosquito nets in these ‘areas’.Footnote 15

Figure 6.1 Colour lithograph attributed to R. Mount, ‘The malaria mosquito under a spotlight, with scenes showing how to avoid catching malaria.’ (London: HM Stationary Office, c. 1943–c.1953.)

More recent scholarly assessments have described malaria as a ‘leading cause of…underdevelopment in the world today…a major contributor to the inequalities between (the Global) North and (the Global) South, and of the dependency of the Third World’.Footnote 16 Many historians who have written about early and mid-twentieth-century South Asia, Africa, Egypt, Palestine, Philippines, Indochina or postwar Mexico, have examined the significance of concerns about malaria in shaping the late imperial and postcolonial world. These scholars have shown that malaria in the twentieth century was not only a recurrent issue in imperial governance and geopolitics; but the disease was also entangled within local aspirations of development and ethnic nationalism.Footnote 17

In reemphasising the significance of European empires in the making of modern medical knowledge, I have drawn upon the extant historiography linking science, medicine and empires. I have also been inspired by an emerging scholarship on postcolonial science which has asserted that empire can be a crucial analytical frame in understanding more recent developments in the sciences.Footnote 18 At the same time, I have been attentive to the ways in which historians in recent years have questioned the exclusive attention accorded to imperial agency in analysing the making of the modern world.Footnote 19 Inspired by these diverse positions, Malarial Subjects has contributed to recent conceptual literature about empires themselves. The history of British Empire in the long nineteenth century cannot be reduced to the activities of the colonial state alone. Instead, each chapter describes the Empire as an occasion for the interaction between the worlds of governance, knowledge and commerce. The Empire was simultaneously an overarching causal agent, as well as an immanent process that was itself sustained by these interactions. It was not necessarily an inflexible, top-down and preordained institutional framework. But rather, the long and violent life of British Empire can be explained by its ability to shape and in turn be reconstituted by various human and nonhuman histories.

‘Morbus Bengalensis’

Non-European colonised groups have featured in different ways in the recent historiography of British imperial science and medicine. One of the most enduring strands of this historiography has acknowledged that science and medicine were crucial means through which imperial rule and violence were inflicted on colonised groups.Footnote 20 Other scholars have argued that the colonial state-endorsed science and medicine were not shaped by the activities of Europeans alone, but rather such forms of knowledge were also built upon the physical and intellectual labour of indigenous groups in the colonised locales.Footnote 21 While extending these insights, postcolonial scholars have further revealed that colonised vernacular groups were not passive recipients of the dictates of imperial science and medicine. These scholars have shown how the contents of the colonial state-informed science and medicine were eventually translated, displaced, reinterpreted and appropriated by the colonised people to suit their own agendas.Footnote 22 Inspired by these different scholarly positions, this section comments on Bengali publications on malaria, quinine and mosquitoes in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. I have focused on a specific South Asian language for the sake of in-depth analysis, apart from my own interests in the region. Besides, Bengal had one of the most enduring exposures to imperial rule in the modern world. It was home to a thriving vernacular print market, as well as one of the earliest cinchona plantations and quinine factories to be set up in the colonial world. Yet it retained the notoriety of being considered as one of the most malarial provinces of the British Empire until decolonisation. This section argues that resisting, translating and reappropriating insights about quinine, malaria and mosquitoes in the Bengali public sphere should not necessarily be regarded as extraneous to the history of imperial medicine. Rather, along with details unfolding in bureaucratic files, commercial private papers, or colonial medical journals, these processes need to be acknowledged as episodes within the history of empire and imperial medicine. I suggest that the history of imperial medicine was shaped through interactions between the more peripatetic concerns of colonial bureaucrats, medical officials, and Europeans pharmaceutical businessmen, on the one hand, and vernacular public cultures, on the other.Footnote 23 This section ends by hinting that in the final decades of British imperial rule, Bengali (often anti-imperial) writings on mosquitoes reflected the various concerns of British colonial officials, multinational charitable organisations, the US military and other dominant players in global governance in the interwar period.

British Indian subjects were not necessarily docile bodies who were inescapably colonised into consuming quinine. Colonised subjects often rejected or criticised medicines prescribed to them by the colonial state, and this constituted an integral aspect of the history of imperial medicine. Indeed, the elaborate disciplinary as well as punitive measures adopted by the British Indian government to enforce the consumption of quinine amongst the colonial subjects indicate the hesitation with which the drug must have been initially received. Indigenous rejection of quinine took various forms. Female tea plantation labourers in North Bengal often refused their daily dosage of quinine by spitting the drug out.Footnote 24 More patrician critics of quinine claimed that the drug was a symbol of moral decadence and excessive reliance upon Western ways of living. An article published in the 1870s in the homoeopathic Calcutta Journal of Medicine, as discussed in Chapter 3, sarcastically renamed Burdwan fever as a ‘cinchona disease’. The article argued that Burdwan fever was a side effect of excessive consumption of quinine in colonial Bengal. Similarly, Bengali medical journals like Chikitsa Sammilani published editorials titled ‘Quinine is malaria’, and in the process refused to distinguish between the cause and cure of disease. These kinds of statements did not merely express doubts about the efficacy of quinine as a therapeutic substance. By equating the quintessential cure with malaria, these critics were simultaneously calling into question the validity of the diagnostic category malaria itself.Footnote 25 Echoing these thoughts, an early twentieth-century Bengali article entitled ‘Malaria Rahasya’ or the ‘Malaria Mystery’ rejected quinine by labelling it as a poison. It also described malaria as an ‘airy-fairy word’, and an ‘imaginary unfounded idea’.Footnote 26

Most Bengali commentators, however, underscored the significance of malaria as an experiential reality, even when they continued to suspect the efficaciousness of quinine.Footnote 27 In a paper read out to the Calcutta Medical Society in the early 1880s on the theme ‘Use and Abuse of Quinine in Fever’, Rakhal Chandra Ghose, a Bengali trained in one of the medical colleges set up by the colonial government, argued that the ‘old sufferers living in the endemic districts of Bengal and constantly imbibing the malarial poison’ were victims of a peculiar form of malarial fever. He called this malarial malady which was unique to Bengal, ‘Morbus Bengalensis’. He asserted that quinine was ‘literally useless’ in curing ‘Morbus Bengalensis’.Footnote 28 These doubts were expressed in the context of the proliferation of various indigenous substitutes of quinine in the Bengali vernacular medical marketplace. Many locally produced pills and tonics were advertised as superior alternatives to quinine in contemporary Bengali almanacs, manuals and pamphlets. These drugs included Atyashcharya Batika (The most wonderful pill), Dasyadi Pachan, Sarkar's tonic, Chaitanya batika (Chaitanya pills), Bijoy batika (Victory pills) amongst others.Footnote 29 All commodities associated with curing malaria, however, were not to be orally consumed. Certain advertisements recommended ritually sanctioned lockets which were supposedly endowed with divine powers that could stave off malaria and its effects.Footnote 30 A range of advertisements claimed that these local commodities were more suited than quinine to combat malaria in Bengal.

Nonetheless, the colonial state and its vernacular subjects did not always adopt completely opposite positions on quinine. The image of a unanimous medical bureaucracy imposing quinine on a reluctant Bengali people did not necessarily hold. A section of English bureaucrats themselves criticised the widespread distribution of quinine amongst ‘Indian patients’. Drawing on various physiological surveys conducted in India in the early 1900s, this group of officials emphasised the differences in the ‘composition of the blood of non–flesh-eating natives of India from that of the blood of the flesh-eating Europeans’. They argued that the red blood corpuscles of local inhabitants in India were characterised by a relative deficiency of haemoglobin, and this rendered the consumption of significant doses of quinine ‘deleterious’.Footnote 31 On the other hand, apart from selling indigenous substitutes of quinine, Bengali shopkeepers and medics in the vernacular marketplaces also innovated their own versions of quinine. While many of them were sceptical about the effectiveness of an imported drug, others were increasingly aware of the credibility the label quinine carried with it, because of its enduring association with the colonial government. As the case of Shashi Bhusan Dutta detailed in the previous chapter suggests, various operators in the vernacular marketplace appropriated the label of quinine to describe their disparate medical products. By the 1890s, the colonial state had installed a network of mechanisms to detect and punish these acts. Contemporary Bengali novelists, as well, shared the governmental perception that the original purity of quinine was being tampered with by Indian rural shopkeepers.Footnote 32

The interactions between state medicine and vernacular medical markets in Bengal were enabled by the increasing participation of Bengalis such as Jodunath Mukhopadhyay as subordinate members in the colonial medical apparatus. Mukhopadhyay pursued multiple careers, and inhabited different cultural worlds. He was educated in the colonial medical institutions, authored various medical manuals in Bengali, and traded in indigenous alternatives to quinine.Footnote 33 Many Bengali medical manuals written by Mukhopadhyay emphasised the virtues of quinine as a remedy for diseases associated with malaria.Footnote 34 At the same time, an advertisement published in March 1888 claimed that he had himself started manufacturing a more effective remedy for malarial fever which he called Sarvajvarankusha, which meant ‘The cure of all fevers’.Footnote 35 This suggests that Bengalis who advertised the virtues of quinine and those who traded in its indigenous alternatives did not necessarily constitute mutually exclusive worlds. In fact, many spokesmen in favour of anti-malarial patent medicine or indigenous alternatives of quinine in Bengal were employed in the colonial medical department.Footnote 36 Therefore, it is not unlikely that directly or indirectly they were also associated with the colonial state's project of popularising quinine amongst the Indians. Bengali advocates of quinine and its indigenous substitutes were often drawn from the same cultural world, and used similar expressions in praise of these competing drugs. For example, appealing to the sensibilities of a Hindu readership, Bengali articles and advertisements referred to both quinine and anti-malarial patent medicines in Bengal as ‘Brahmastra’, an invincible weapon described in Hindu mythology. Bengali medical publications did not pursue the single-minded agenda of contesting the curative properties ascribed on quinine. These were also sites in which the relevance of quinine was reasserted before a Bengali-reading audience.Footnote 37

Those who wrote about malaria, quinine and its indigenous substitutes in Bengali medical journals, books, newspapers, magazines and almanacs (and who were cited in the advertisements of various anti-malarial medicines in the late nineteenth century) mostly belonged to a class of bilingual Bengali men, who were trained in the emerging medical colleges in and around Calcutta. A majority of these Bengali authors, such as Mukhopadhyay, held ‘a license for medicine and surgery’ (LMS). Others possessed more respectable degrees such as Doctor of Medicine (MD) or a baccalaureate degree in medicine (MB).Footnote 38 These qualifications, which were recognised by the colonial government, enabled these authors to seek employment in a hierarchy of positions within the colonial medical establishment ranging from assistant surgeons to resident medical officers in government hospitals.Footnote 39 Bengali writings on malaria and its cures were authored not only from Calcutta, but also from other parts of Bengal including Chandannagore, Chinsurah, Murshidabad and Bolpur.Footnote 40 As already noted, apart from doubting the efficacy of quinine, some of these authors questioned the existence of malaria itself.Footnote 41 Others attributed malarial epidemics in Bengal to flaws in government policies.Footnote 42 However, most of these texts echoed the dominant concerns of the colonial government, and circulated significant contemporary medical theories about malaria and its cures.Footnote 43

While claiming to translate and disseminate knowledge about malaria and quinine in the Bengali language, these texts were highly creative and original works in themselves.Footnote 44 They displayed their authors’ ability to blend wisdom acquired from superiors in the colonial medical service, college lecturers and English textbooks, on the one hand, with experiential references to more intimate landscapes, places, vegetation, cultural icons and events encountered in Bengal, on the other.Footnote 45 These were cosmopolitan texts in which references to ancient Ayurvedic verses and nineteenth-century British medical commentators (such as John MacCulloch) were intimately interspersed; some of these Bengali texts contained quotations in Latin, Sanskrit and English.Footnote 46 In his book-length treatise on malaria published in 1878, assistant surgeon Doyal Krishen Ghosh indicated that malaria was not only an enigmatic medical problem, but also a moral problem that was caused by laziness, inadequate sleep, excessive sexual activity and undisciplined diet.Footnote 47 Ghosh, therefore, combined insights from English medical journals with lessons prescribed in Bengali medico-moral manuals, which were widely in circulation in the print market.Footnote 48

These texts did not represent a distortion of preordained imperial medical knowledge. But rather, along with English medical journals and colonial bureaucratic correspondence analysed in Chapters 2 and 3, these Bengali texts were also integral sites where imperial insights about malaria were reshaped and consolidated. As liminal go-betweens, their authors played an important role in shaping the vocabulary in which literate Bengalis, who were crucial agents in the imperial world, addressed the disease. Their mediation enabled the enmeshing of European medical categories with Bengali cultural repertoires, which paved the way for various literary liberties. If quinine was referred to as a ‘brahmastra’, malaria was described as a ‘rakshashi’ (female demon); a ‘jujuburi’ (witch); ‘jamopam rakshash’ (‘a demon comparable to Lord Yama, the mythical God of Death’; and a ‘dabanol’ (‘forest fire’).Footnote 49 When he mentioned malarial fever as ‘maloyarir jvar’ in his well-known novel Arakshaniya (The Unmarriageable), the iconic Bengali writer Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay hinted at the way in which the word malaria may have been slightly tweaked in its everyday colloquial usage in certain parts of contemporary Bengal.Footnote 50 In the same novel, Chattopadhyay suggests how young women ostensibly suffering from malaria in poverty-stricken, rural, patriarchal Bengal were perceived as ugly and unmarriageable. Arakshaniya represents malaria not as a distant governmental jargon, but as an everyday reality that shaped, by the 1910s, experiences of intimacy and romance in Bengal.Footnote 51

Bengali writers on malaria shaped attitudes not only of the manual and novel reading public in Bengal, but of the colonial state also. Despite punishing fraud and adulteration, the colonial state itself drew upon various local cultural symbols to popularise government quinine amongst the Indian subjects. These state-initiated innovations also shaped the interactions between local cultural icons and apparently secular medical items. As discussed in the previous chapter, the imperial postal department distributed a signboard in the 1890s that described quinine as a remedy gifted by the Hindu deity Lord Shiva to the ailing peasants of rural Bengal.Footnote 52 The colonial state also initiated the translation of advertisements of government quinine from English into a range of South Asian languages, including Bengali. The publicity for government quinine in Indian regional languages and the use of religious icons like Lord Shiva in quinine posters must have been made easier by the increasing presence of South Asians, including Bengalis, in different levels of colonial medical governance. Bengalis, whether in their capacity as medics trained in the colonial medical colleges in India, or as employees in the colonial bureaucracy drafted unpublished routine correspondence in English, contributed to English medical journals and wrote book-length treatises in English. Their opinions may not necessarily have formed the backbone of imperial malaria policy. However, the fact that their writings made it into journals such as the Indian Medical Gazette indicates that their insights about the locality were given cognizance by the colonial medical establishment.Footnote 53 In Chapter 3, I have suggested that some Bengali members in the British Indian administration, such as Sunjeeb Chunder Chatterjee and Gopaul Chandra Roy, played significant roles in shaping colonial discourse about Burdwan fever. In a letter addressed to the Secretary of the Government of Bengal in 1863, Chatterjee, who was one of the first Bengali members in the colonial bureaucracy and also the elder brother of the pioneering Bengali novelist Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay, recommended intense anti-malarial administrative intervention by the colonial state in the interiors of Bengal. That this letter was cited again seven years later in official correspondence suggests that his recommendations were taken seriously.Footnote 54 Roy, who studied medicine in Glasgow and London, was employed as inspecting medical officer of dispensaries in Burdwan, and in the 1870s wrote a book on Burdwan fever. That the book was published simultaneously by different English firms in London and Calcutta, and went into multiple editions suggests that Roy's work attracted a considerable audience.Footnote 55 Such widespread interest in how the members of the colonised society defined malaria and its solutions was not exceptional. One might recall that the Viceroy Lord Northbrook declared in 1872 a prize of Rs. 1000 for the best essay written by a ‘native’ sub-assistant surgeon on the causes and prevention of Burdwan fever.Footnote 56 It can be argued that regional expertise asserted by Bengalis writing on malaria in English was appropriated by the imperial project of pathologising colonised lands, landscapes and people. By sharing intimate information about plants, places and landscapes in Bengal, these writers added greater depth, texture and local flavour to imperial medical narratives about malaria.

The interchange between South Asian colonised voices and the colonial state manifested in other ways. The Bengali medical journal Bhishak Darpan published an article in 1911 entitled ‘Ayurbedey Malaria’ (‘Malaria in the Ayurveda’) by a physician Saracchandra Lahiri, who asserted that the authors of key texts of Ayurveda in ancient India already knew the aetiology and cures of malaria.Footnote 57 In a speech delivered as the President of the Imperial Malaria Conference held in Shimla in 1909, H.H. Risley almost anticipated Lahiri's opinions when he argued that the authors of Atharvaveda knew about malaria and its cures.Footnote 58 Therefore, Bengali revivalist ideologues in the immediate aftermath of the Swadeshi movement in the 1900s appropriated colonial medical categories such as malaria to assert the relevance of Ayurveda in modern India. In turn, senior colonial officials such as Risley invoked ancient Indian wisdom to assert the enduring historical roots of colonial medical categories such as malaria in the subcontinent.

Therefore, notions about malaria and quinine were not unilaterally imposed on Bengal by the colonial state. Imperial notions of malaria and quinine were reshaped and sustained by Bengali idioms, icons, words and politics. As evident from these examples, these interactions informed the intellectual and material meanings of malaria and quinine in Bengal. These interactions also influenced the routes and networks through which the government organised the circulation of quinine in the province. Well before the government embarked in the 1890s and 1900s on a policy of aggressively enforcing the consumption of quinine in the interiors of South Asia, there thrived in Bengal a vernacular medical market in which various medical products, indigenous as well as imported (such as quinine), circulated.Footnote 59 Advertisements published in Bengali newspapers, almanacs and medical manuals in the 1870s and 1880s indicate that Bengali operators in local medical marketplaces already devised networks through which to circulate their products into the interiors of districts, subdivisions, ‘outposts’, police stations, and ‘small, remote, and cluttered villages’.Footnote 60 They sold their medical products in the various corners of the province through many sites closely associated with the colonial state: merchants’ offices, tea plantations, government medical stores, veterinary dispensaries, district boards, municipalities, port commission offices, railway stores, collieries and dispensaries.Footnote 61 They also recruited various ostensibly credible figures in rural Bengal such as teachers, pundits, postmasters, sub-inspectors, head-constables, the rural gentry, ‘native doctors’ and kavirajas to sell anti-malarial drugs in lieu of a commission.Footnote 62 These advertisements instructed prospective consumers to request for medicines from Calcutta-based firms directly through the post, and to make payments through various postal innovations like money order and bearer's post.Footnote 63 As I have elaborated in the previous chapter, many of these strategies would in subsequent decades form the backbone of aggressive quinine distribution efforts initiated under the watch of the government.

Similarly, regarding attitudes towards mosquitoes, the views of the colonised people and of the imperial medical entomologists often coalesced. It may be pointed out as a digression that in his address on the occasion of awarding the Nobel Prize in medicine to Ronald Ross, the rector of the Caroline Institute reportedly claimed that Ross's discovery was anticipated by East African tradition. He explained his point by suggesting that ‘negroes in East Africa use the same name for the mosquito and malaria’.Footnote 64 While both the politics and content of the rector's statement deserve greater scrutiny, it is undeniable that in the imperial world of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, many groups of people, besides imperial medical entomologists were concerned about mosquitoes. I have shown in Chapter 5 how prejudices against insects more generally and mosquitoes in particular were shared between the worlds of colonial plantation economy, late Victorian advertisements, sanitary governance, entomological laboratory and Bengali literature.

In British India, the government continued to organise mosquito-killing initiatives into the interwar period.Footnote 65 Cleansing the environment of mosquitoes was seen to be part of a wider sanitising project through which the colonial state asserted itself as the custodian of medical well-being in the colony.Footnote 66 In the early twentieth century, the British Empire in India, however, was not the only global power which prioritised protection from or annihilation of mosquitoes as a governmental agenda. These concerns were shared by fledgling multinational philanthropic organisations such as the Rockefeller Foundation, which started interacting closely with regional caretakers of development and health across the world in Italy, Egypt and Brazil.Footnote 67 Mosquitoes also featured prominently in the military predicaments of the United States. This was manifested not just in manuals that instructed soldiers engaged in overseas military expeditions about the most effective means to protect themselves from malaria and mosquitoes.Footnote 68 I have indicated that mosquitoes even emerged as a symbol of legitimate US military aggression in the early 1950s when a squadron of the US air force during the Korean War was named after mosquitoes. Photographs taken during this period from Malaysia, Mauritius, Trinidad and Ghana, and currently held at the archives of the Royal Commonwealth Society in Cambridge, suggest that the obsession to seek protection from malarial mosquitoes dictated patterns of entomological research, urban planning, architectural design and housewifery curriculum across the colonial world.Footnote 69 These concerns even made their way into children's comic literature. Herge's 1930 work Tintin in Congo warns readers about the perils of venturing into the interiors of Belgian Congo without a mosquito net!Footnote 70

In this wider context, as I have indicated in the last chapter, mosquitoes also attracted considerable attention in Bengali publications across a range of literary genres including fantasies, social treatises, educational pamphlets, crime fiction, comic short stories, poems, medical manuals and popular magazines. Of course, these literary works represented disparate aesthetic, satirical and political projects, and most of them did not directly promote the medicalisation of mosquitoes. However, it is significant that over the same period both imperial medical entomology and these Bengali literary texts contributed to the metamorphosis of mosquitoes into objects of enduring public spectacle. Even when Bengali humorous pamphlets and short stories caricatured these entomological projects, they were reminiscent of the global reality that public health officials were indeed engaged in a ‘war with mosquitoes’.Footnote 71 Some of these texts echoed medical entomology, overtly or symbolically, to suggest that mosquitoes were villainous enemies of humans, and therefore, should be exterminated.Footnote 72

In the 1920s, many Bengali books about public health and medicine identified malaria as one of the severest problems that plagued the ‘desh’ – the country. Although written at the height of anti-imperial nationalist movements in South Asia, these books rarely invoked the vision of an overarching Indian nation. Instead, words like ‘desh’, ‘bangla’, ‘bangadesh’, ‘bangladesh’ were frequently used to conjure up the image of a Bengali homeland.Footnote 73 Mosquitoes, as vectors of malaria, were described as inimical to the ‘desh’ – the Bengali homeland.Footnote 74 The villages – ‘Gram’ or ‘palligram’ – were projected as particularly vulnerable.Footnote 75 These texts appealed to the colonial municipal governments for devising mechanisms to protect rural Bengal from the virulence of malarial mosquitoes.

Yet, the purging of mosquitoes from the homeland, and the reconstruction of rural Bengal, it was argued, could not be the exclusive prerogative of the municipalities. It was recommended that these projects could only be emboldened through collective action involving the participation of Bengali society more generally.Footnote 76 To that end, authors of these books instructed their readers to establish associations such as ‘Pallisamiti’ (‘Village association’), ‘Malaria Nibaroni Samiti’ (Society for the prevention of malaria’) and ‘Swasthya-raksha samiti’ (‘Society for the preservation of health’).Footnote 77 These organisations were supposed to undertake various steps to protect the ‘desh’ of the Bengalis, and particularly the villages of Bengal from mosquitoes. These steps included not just the mobilisation of resources from within the localities for the destruction of the habitats of mosquitoes by sanitising puddles; putting kerosene into pits of stagnant water;Footnote 78 improving rural drainage networks;Footnote 79 replacing old decaying vegetation with newly planted trees;Footnote 80 and informing villagers about the means to protecting themselves from mosquitoes.Footnote 81

These authors also pointed out that the goal of minimising the threat of malarial mosquitoes necessitated that these organisations set up free primary schools and schemes to reduce poverty; encourage agriculture and the weaving industry; revive a culture of athletics and physical training; establish rural courts to adjudicate local disputes; and put together plebeian Hindu gatherings, such as ‘dharmasabha’ and ‘harisabha’.Footnote 82 According to these texts, the control of malaria and its vectors in Bengal was connected to the restoration of social cohesion, harmony, prosperity and religious values within rural communities. At the same time, it was argued that protection of the ‘desh’ from mosquitoes could not be ensured through activities in the public sphere alone. The shared project of resisting mosquitoes required, it was claimed, the submission of individual householders to specific codes of morality and everyday routine. These included the obligation to keep the household clean and tidy; to cover the body with clothes at all times; to fumigate the home in the evening with flames of incense sticks and camphor;Footnote 83 to remain inside a mosquito net and within the secure marital confines of one's home in the evenings and at night.Footnote 84

Some of these instructions to the householders were particularly meticulous in their detail. A book published in 1927, for example, argued that anopheles mosquitoes were especially attracted to certain colours (such as navy blue, dark red, brown and scarlet), and that householders should avoid sleeping in mosquito nets, which bore such colours.Footnote 85 The same book began by suggesting that countries, which had effectively eradicated malaria and its insect vectors, were relatively more ‘cultured and politically free’ than Bengal.Footnote 86 It claimed that widespread malaria in Bengal was a reflection of a deeper cultural crisis; a crisis resulting from the inability of the Bengalis to retain their indigenous culture during colonial rule as well as their failure to embrace ‘western culture’ conclusively.Footnote 87 In this phase of cultural flux, continued the author, the Bengalis had given in to excessive consumption, material pleasures and ‘fashion’.Footnote 88 To resist the onslaught of malarial mosquitoes, he urged the Bengalis to observe restraint and self-discipline in their everyday life.Footnote 89 Therefore, the challenge of protecting the ‘desh’ from mosquitoes opened up the need for greater sanitary governance, as well as social and moral discipline in rural Bengal.

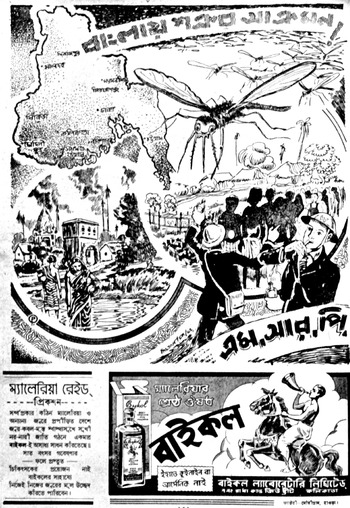

The perception that mosquitoes were a threat to Bengali health, household and homeland was reflected in the world of radio broadcasts, literature and advertisements of the time. Betar Jagat, a widely circulated magazine associated with the radio-broadcasting agency, published articles in consecutive issues in the 1930s, alerting the Bengali householders of the crucial role they could play in restraining mosquitoes.Footnote 90 Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay's novel Palli Samaj (Village Society), published earlier in the 1910s, hints at how collective social projects against malaria and its vectors were appropriated within contemporary programmes of rural reconstruction.Footnote 91 In tune with the wider trends of the period, the need to protect the ‘desh’ from malarial mosquitoes was also articulated in military vocabulary. An advertisement of an anti-malarial drug (Figure 6.2), Baikol, published during World War II in 1942, compared the threat of mosquitoes to the fear of ‘raids’ carried out by Japanese fighter aeroplanes during those years in Bengal. The advertisement carries the caption ‘The enemy attacks Bengal’, and depicts a gigantic mosquito followed by waves of smaller mosquitoes hovering over the map of Bengal.Footnote 92

Figure 6.2 Advertisement of ‘Baikol’, Ananda Bazar Patrika Saradiya, (1942), p. 172.

Similarly, in a lecture delivered to the ‘Anti-malaria Society’ earlier in August 1923, Rabindranath Tagore, already a Nobel laureate in literature, described mosquitoes as one of the ‘greatest enemies of Bangladesh’ which needed to be ‘evicted’ from the homeland. In a speech replete with words such as ‘war’, ‘weapon’ and ‘killing’, Tagore asserted that the shared project of destroying mosquitoes could strengthen solidarity amongst the Bengalis much more effectively than lofty ideas such as ‘desh’ (country or homeland) and ‘swaraj’ (self-determination).Footnote 93

Therefore, significant (often anti-imperial) voices in Bengal shared the anxieties of British imperial officials, multinational philanthropic organisations, and the US military about mosquitoes, even when they pursued different political and cultural projects. These overlapping concerns suggest that protection from mosquitoes emerged as one of the dominant agendas of global governance during the first half of the century. If indeed, as Warwick Anderson suggests, medicine and hygiene were appropriated in the ‘civilising process’ of the interwar period, then it can be argued that various Bengali publications about malarial mosquitoes were also implicated within those processes.Footnote 94A few sources suggest that Bengali biases against insects preceded the global recognition of mosquitoes as the vectors of malaria. These texts which were published prior to the establishment of the imperial discipline of medical entomology in the 1890s had already begun featuring bugs or objects associated with bugs as symbols of moral decadence.Footnote 95

British imperial medicine, therefore, was not merely constituted by the policies, violence, disciplinary mechanisms and classificatory practices shaped by senior British representatives of colonial governments. Imperial medicine was also a product of the ways in which the colonised resisted, internalised, reinterpreted, reinforced, interacted and competed with, and even anticipated governmental impositions. This book contributes to the ongoing efforts to narrate the history of imperial violence, while being simultaneously attentive to the close interactions between imperial regimes and the public cultures of the colonised.

Nonhuman Empire

The history of malaria, as detailed in this book, also reveals various entanglements of the British Empire with nonhumans (including plants, animals and objects), more generally, and not just mosquitoes. Colonial medical officials, bureaucrats and industrialists, while commenting on malaria and its possible cures, invoked nonhuman animals and plants recurrently. The linking up of malaria with nonhuman animals took various forms. It was not confined to the identification of anopheles mosquitoes in the 1900s as the insect vector for malarial parasites. Monsters, for example, were depicted as a symbol of malaria in a late-nineteenth-century advertisement for anti-malarial pills.Footnote 96 Architectural designs of houses within tea plantations in Assam in British India in the 1940s were shaped by the ostensible purpose of protecting the planters simultaneously from malaria and wild animals.Footnote 97 These trends have survived in postcolonial India. Recent journalistic reports have suggested that the combined threats from snakes and malaria shape military confrontations in the forests of Central India between Maoists, on the one hand, and the state-sponsored militia, on the other.Footnote 98 I have noted how the history of malaria in British India reveals a hierarchy of plants in the imperial imagination. Plants appropriated within the cosmopolitan colonial plantation economy such as cinchonas, eucalyptus or sunflower were celebrated for their therapeutic properties. Various other plants, which were described as ‘wild’ ‘undergrowths’, even when they were intimately associated with the life-worlds of various groups of people in colonial India, as Chapters 1 and 3 have shown, ran the risk of being labelled as unwanted excesses and pathological sources of malaria.

Historians have exposed, in different ways, the importance of nonhumans (particularly animals) in imperial medicine.Footnote 99 Building on these existing works, this book has carried out the methodological challenge of narrating the significance of nonhumans in imperial history, while retaining a critique of scientific determinism. In order to simultaneously resist tendencies of anthropocentrism and scientism in the history of the British Empire, it has explored the ways in which British Empire and medical knowledge about nonhumans were co-constituted. Indeed, the Empire was deeply invested in the production of medical knowledge about nonhuman animals, plants and objects. I have argued that the medical properties attributed to cinchona plants, objects described as malarial, the drug quinine and anopheles mosquitoes did not unfold in a historical and political vacuum. Instead, the exigencies and apparatuses of British imperial rule, to a considerable extent, informed them. At the same time, these nonhumans were not passive constructs, but rather they were integral to the structural, ideological, commercial, prejudicial, biopolitical and physical foundations of the British Empire itself.

Constructs such as cinchonas, quinine, malaria and mosquitoes were amongst the many historical adhesives which bound up disparate groups and distant regions as components of a wider imperial world. As this book demonstrates, they deepened ‘connections’, ‘tensions’ and ‘fractures’ between the imperial realms of British India, Dutch Java, French Algeria, German and British Africa, Mauritius, Burma and the West Indies, while holding together disparate groups claiming to represent scientific and medical knowledge, pharmaceutical commerce, colonial governance and vernacular cultures.Footnote 100 The drug quinine and its source cinchona plants reinforced the ideological self-image of the British Empire as a simultaneously benevolent and profit-making enterprise. And yet, the history of the production and maintenance of objects and organisms described here reflects also the prejudices about race, colour, indentured labourers and primitives which were intrinsic to liberal empires of the nineteenth century.Footnote 101

This book has shown that nonhumans were entangled in histories of imperial biopower at least in three different ways. First, nonhumans such as cinchonas, objects described as malarial, quinine and mosquitoes featured as instruments of imperial biopolitics.Footnote 102 Discourses and practices relating to them reinforced control over lands, landscapes and people which explain the revealing overlaps amongst geographies of plantations, disease and empire.Footnote 103 Imperial discourses about malaria and its cures constructed colonial subjects not only as potential labourers, who required remaining healthy and productive, but also shaped them as potential consumers, who needed to be disciplined to consume various curatives. Secondly, our understandings about subjects of imperial biopower need to be extended beyond the human to include insects, plants and inanimate objects.Footnote 104 Much like the colonised Indians, cinchona plants, the drug quinine, objects designated as malarial as well as mosquitoes were subjected to imperial regimes of classification, surveillance and knowledge-production. Thirdly, distinctions between humans and nonhumans, considered by many commentators as fundamental to biopower, were asserted as well as blurred in the history of imperial medicine in British India.Footnote 105 This was particularly because of the simultaneous operation of the twin processes of anthropomorphism and dehumanisation in British imperial history.Footnote 106 The feminisation of cinchona plants imported from South America as ‘fairest of Peruvian maids’ and as ‘delicate, beautiful and tender’, as evident in Chapter 1, happened at the precise moment in which colonised ‘natives’ and ‘aborigines’ supposedly immune from malaria were being projected to inhabit ‘the state of nature’. In different parts of the book I have shown how imperial medical commentators claimed that the lower animals and colonised aboriginal groups (in Chapter 2), indigenous quacks and locusts (in Chapter 3), parasites and primitives, urban labourers and mosquitoes (in Chapter 5) shared analogous properties. Quinine, as I have explored in Chapter 4, appears to have personified various racial hierarchies of colour. In colonial factory discourses, whiteness symbolised one of the most consistent indicators of quinine's purity, while brownness and yellowness featured amongst the most obvious markers of the impurities that had corrupted the drug.

Finally, I have claimed that nonhumans such as cinchonas, objects described as malarial, quinine and mosquitoes, apart from being shaped by the histories of the British Empire, were also amongst its integral physical constituents. Both the Empire and its co-constituents can also be understood as ‘localised’Footnote 107 socio-material networks. I have explored networks constituted, for example, of Wardian cases, steamers, small pots, herbariums, plantations, royal gardens, planters, bureaucrats, economic-botanists, geographers (in Chapter 1); of decaying vegetation, friable granite rocks, water casks, mouldy bed sheets, stale mushrooms, geologists, meteorologists, chemists, colonial administrators (in Chapter 2); of sunflower, paddy, bamboo, jute, ‘undergrowths’, physicians, landed proprietors, local officials, vernacular tradesmen (in Chapter 3); of cinchona barks, alkaloids, colouring matter, labelled bottles, sealing wax, carmine, European pharmaceutical families, office of the Secretary of State for India, chemical examiners, managers of colonial factories (Chapter 4); and of insecticides, parasites, fishes, hyacinths, tinsmiths, coolies, planters, parasitologists, sanitary commissioners and Bengali fiction writers (in Chapter 5). These social-material amalgamations shaped and sustained not only cinchonas, malaria, Burdwan fever, quinine and mosquitoes, respectively, but also constituted various moments and structures of the British Empire as well.

The British Empire was an extensive technopolitical, material-discursive and natural-cultural formation.Footnote 108 Humans alone did not constitute the British Empire. Similarly, cinchonas, malarial objects, quinine and mosquitoes did not represent a self-contained domain of nonhumans. I have argued that the Empire as well as these nonhuman co-constituents can be deconstructed into heterogeneous associations of humans and nonhumans, subjects and objects. Invoking actor-network theory, perspectivist anthropology, sociology of sciences and post-Marxist feminism, I claim that the British imperial apparatusFootnote 109 as well as its co-constituents detailed in this book may be described variously as ‘mangles’,Footnote 110 ‘inter-subjective fields of human and nonhuman relations’,Footnote 111 ‘cyborgs’Footnote 112 and ‘collectives’ which traversed the domains of ‘object-discourse-nature-society’.Footnote 113 Therefore, I have refused to prescribe other-than-humans (particularly nonhuman animals, interspecies assemblages, or cyborgs) as definite agents of transgression and resistance.Footnote 114 This is because such figures themselves were often implicated within imperial structures. Thus this book has reinforced efforts to go beyond dominant anthropocentric conceptions of Empire, while claiming that nonhumans themselves did not necessarily inhabit a preordained or self-contained realm. It has also reasserted the extraordinary significance and violence of empires in the making of modern medicine, while contesting the assumption that imperial agency can be critiqued comprehensively by examining the activities of Europeans alone.