Muted Slaves: On Transplanting Cultures

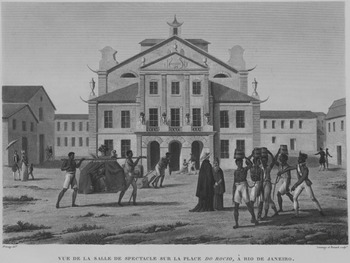

The cover of this book shows a square in Rio de Janeiro during the second decade of the nineteenth century, based on a drawing by the French writer, artist and traveller Jacques Arago (1790–1855; see Figure 1.1). Founded in 1565, since 1763 Rio had been the capital of the Viceroyalty of Brazil, belonging to the Portuguese Empire. In 1808, in response to the Napoleonic Wars, the Portuguese royal court made Rio its official residence. Central in the background of Arago’s work one sees the majestic façade of the Theatro São João (renamed Theatro São Pedro de Alcântara after the fire on 25 March 1824), which opened in 1813 and had been built after the model of the São Carlos Theatre in Lisbon. It was certainly the most ambitious civic building in Rio de Janeiro at that time, erected to replace the old opera house and suitable for the city’s new role as capital of the Portuguese Empire.Footnote 1 Arago’s Vue de la salle de spectacle sur la place do Rocio, à Rio de Janeiro was subsequently engraved by Lerouge and Robert Bénard, and published in 1824 in the Atlas historique to Louis de Freycinet’s Voyage autour du monde.Footnote 2

Figure 1.1 J. Arago, Vue de la salle de spectacle sur la place do Rocio, à Rio de Janeiro (engraved by Lerouge and Bénard). Banco Itaú – Edouard Fraipont/Itaú Cultural, São Paulo

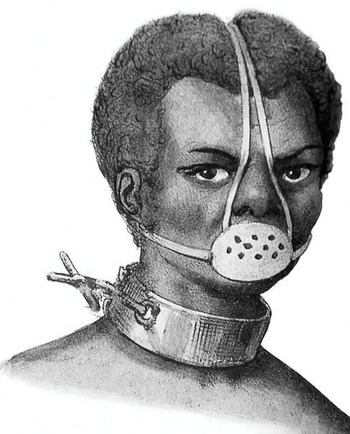

The building appeared in multiple nineteenth-century drawings and engravings of Rio, including those by Thomas Ender, Jean-Baptiste Debret, Karl Wilhelm von Theremin and Friedrich Pustkow. Frequently, artists enlivened the scenery with the depiction of slaves somewhere in the square, almost so as to contrast with and underline the theatre’s splendour. If in Debret’s and von Theremin’s depictions the slaves appear as just one of several aspects of social life in Rio, in Arago’s portrayal of the square the slaves take centre stage, clearly standing out against the orthogonal frame created by the theatre and emphasising the contrast between the great building, as a sign of the Portuguese court’s civilising project, and the misery and violence of slavery, seemingly as a by-product of the continent’s Europeanisation. Commenting on Arago’s engraving, Freycinet only indicates that ‘one could receive an idea of the exterior architecture of the Theatre San-Joaõ [sic], and of the taste that determined its construction. The inside is equally agreeable, even if it is a little too big for the city and fills itself only on the occasion of great festivities.’Footnote 3 The slaves, so prominently represented in the illustration, go without mention, as if they were to be understood as a natural aspect of life in the New World. Unlike many travellers and commentators, however, Arago lived in Brazil for long periods and died in Rio; and his ideas about the role of slavery in the New World were also different from those of many of his contemporaries. In his Souvenirs d’un aveugle, the author explicitly refers to the striking contrast between the beauty of the local landscape and the cruelty of slavery, a cruelty that is represented in many of the works he painted in Brazil, in which he frequently depicts the punishment of slaves.Footnote 4 As shown in his Castigo de Escravo (1839), the punishment of slaves also included the covering of their mouths. Although slaves were usually allowed to sing, and in some cases were even made to perform in choirs and orchestras, the depiction in his famous drawing from Rio almost seems intended to highlight this irony in its juxtaposition of a European style opera house with local slaves (see Figure 1.2). Further complicating the situation, as the next chapter shows, some black Brazilians, usually freed slaves, appeared as patrons in some of the theatre’s most highly prized seats.Footnote 5

Figure 1.2 Jacques Arago (sketch), Châtiment des esclaves (Brésil). Bibliothèque nationale de France

Written after he had lost his eyesight, Arago’s memoirs placed an emphasis on contrasting visual impressions that became part of the book’s dramatic strategy in representing Brazil. For instance, playing on an important topos in Italian travel writing, he notes that the impressions of natural beauty one received when entering Guanabara Bay were superior to those encountered on approaching Genoa, Naples or Venice. At the same time, however, he could not find in Rio de Janeiro many buildings that caught his attention, with the exception of the aqueduct and the opera house. The architecture of the royal palace, even that of the royal chapel with all its gold and luxury, did not seem particularly interesting to him, although he noted a strong presence of music in the city, and he was astonished to hear castrati singing in the church. Like other travellers, Arago therefore was stunned to see such an imposing theatre in this city, and mentioned that the names of Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides were written on the theatre curtain. Slanderously, he concluded: ‘This is all that exists of Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides’: a token reference to European civilisation, but no more. In other words, Arago seems to have been acutely aware of the contrast between the promise associated with the theatre building and the scenes of cruelty he depicted in the square in front of it.

Many contemporary writers commented on the contrast between the presence of European culture in Brazil, including the role of Italian opera, on the one hand, and the impression left on them of the country’s nature and of what they referred to as savages, on the other. Arago, in his work, goes beyond this common feature, outlining in detail his experience of violence and the objectification of slaves, thus stressing the contradictions involved in transplanting cultural models from one world to another.

Opera and National Identity

Italian Opera in Global and Transnational Perspective looks beyond the role of Italian opera in the New World and in Brazil. Our book investigates the impact of transnational musical exchanges on notions of national identity associated with the production and reception of Italian opera in the world. Covering parts of Europe, the Americas and Asia, the case studies assembled in this volume exemplify the effects of the European and global expansion of Italian opera during the long nineteenth century, and discuss the impact of this process on notions of italianità in different parts of the world and at home in Italy. As a consequence of transnational exchanges involving composers, impresarios, musicians and audiences, ideas of operatic italianità constantly changed and had to be reconfigured, reflecting the radically transformative experience of time and space that, throughout the nineteenth century, turned opera into a global aesthetic commodity.

Since the seventeenth century, music and especially opera have frequently been used as signifiers of national identity. There is a long tradition that especially associates vocal music with Italian models. The composers Michael Praetorius, Christoph Bernhard, Antoine Maugars and John Playford, among others, were all concerned with defining what they considered the Italian style or manner of singing, often referencing Giulio Caccini’s Le Nuove Musiche, a collection of monodies and songs for solo voice and basso continuo first published in Florence in 1602. The German singer and composer Bernhard, who was a pupil of Heinrich Schütz and had travelled to Italy around the year 1650, was among the few to recognise three different Italian styles of singing (Roman, Neapolitan and Lombard), thus indicating that the Italian peninsula could not be envisioned as a monolithic culture.Footnote 6 In France, Charles de Saint-Evremond, in his book Sur les Opera [sic] (1684), took the view that ‘Hispanus flet, dolet Italus, Germanus boat, Flander ululat, et solus Gallus cantat [the Spaniard weeps, the Italian suffers, the German roars, the Flemish shouts, and only the Frenchman sings]’.Footnote 7 Among many others, his work was quoted in 1708 by the German writer Barthold Feind, providing evidence of Europe’s wide circulation of books on opera. Even earlier, in 1681, the French Jesuit Claude-François Menestrier had tried to identify the musical character of different nations, later used to define national styles.Footnote 8 Like many of the authors and composers quoted here, Menestrier had himself travelled to Germany and Italy, and was an expert not just on music and opera, but on ballet too.

During the eighteenth century, a large number of related contributions dominated musical debates, starting with historian François Raguenet’s comparison of Italian and French music of 1702,Footnote 9 continued a few years on by the early music critic Jean-Laurent Le Cerf de la Viéville. Many of these arguments were picked up later in the century by Jean-Jacques Rousseau during the famous Querelle des Bouffons, and revived again during the fights between Gluckistes and Piccinistes.Footnote 10 An idea of Italian music being mostly about performance continued to mark these debates, as demonstrated by the philosopher and co-editor (with Denis Diderot) of the Encyclopédie, Jean le Rond d’Alembert. Summarising the debates of the past few decades, he concluded: ‘In this century, there is some sort of fatality attached to what comes to us from Italy. All gifts, good or bad, that it wants to give us are problematic.’ Or even:

In music, we [the French] write and the Italians perform [exécutent]. In this sense, the two nations are the image of those two architects that presented themselves to the Athenians for a monument the Republic wanted to build. One of them spoke extensively and very eloquently about his art; the other, after listening to him, said only these words: what he said, I will do.Footnote 11

What these different authors had in common was their attempt to define what was particular to Italian singing and opera; these traits were understood as a direct reflection of Italian national character, usually without reference to local conventions, or exchanges between Italian and non-Italian traditions. While many authors idealised what they considered the Italian character in the arts, others expressed fatigue, as Eugène Delacroix suggested, many years on, when commenting on the ‘eternal and often blind devotion to everything that comes from Italy’.Footnote 12 Italians rarely intervened in these debates, creating what the historian Fernand Braudel, writing about Italian art in the sixteenth century, has described as an asymmetrical balance between ‘the inside and the outside’.Footnote 13 A rare exception was the eighteenth-century Florentine composer and music theorist Vincenzo Manfredini; he positioned himself against the ‘Germans’, who supposedly interfered in Italy’s operatic scene, despite the fact that he himself wrote operas for the Russian court, and also died in Russia in 1799.Footnote 14

As we have seen above, Rousseau’s writings, and the responses they received, were particularly influential in associating musical styles with national identities, an idea reflecting linguistic conditions as well as the development of specific musical and operatic genres.Footnote 15 During the nineteenth century, the drawing of connections between music and national character assumed new dimensions in political and aesthetic debates, partly due to the idea of reading opera as a contribution to processes of national and political emancipation. The extent to which opera was intended or understood to take a position within the political battles of national movements remains a matter of debate among opera scholars and historians.Footnote 16 These controversies notwithstanding, the frequency of references to national character in nineteenth-century debates on opera and music is striking and certainly contributed to reading opera in a national key – despite the increasingly transnational movement of troupes, audiences and the repertoire; and despite the fact that most composers were influenced by a broad range of cultural and musical experiences that could hardly be reduced to one national tradition. Due to Italy’s role in the invention and historical development of opera, notions of italianità – used with reference to different operatic genres, styles of singing or particular productions – are particularly common in the musical press, in literature and in the scholarly and pedagogical works of the time. As a consequence, these sources form an important basis for the analysis of how italianità was constructed and of what commentators had in mind when they related notions of national character to music. While historians have investigated how ideas of Italian national character have been used in different political contexts,Footnote 17 this has not been a major topic of research in opera studies. Therefore, the construction of a relationship between music and italianità within the increasingly interconnected world of the nineteenth century demands critical attention from a new, transnational perspective. Our book takes a global perspective on operatic discourse, examining how notions of italianità were constructed in exchanges between political and cultural actors of different national origins, and how these notions related to specific local, national and in some cases imperial contexts where the Italian repertoire or Italian productions played a role. Rather than taking operatic italianità as a given, our book looks at how such notions were constructed and debated under the increasingly transnational and global conditions of operatic production. While recognising the extent to which italianità became a transnational and global commodity during the long nineteenth century, from a methodological point of view our approach questions the validity of national categories of analysis when writing the history of opera.Footnote 18

Our book approaches this topic through a number of specific (mostly local) case studies on nineteenth-century opera production in the Americas, Europe and Asia. Latin America is particularly important in the book’s geographical scope due to the early and wide diffusion of Italian opera in both Lusophone and Spanish America, and to the role played by Italian troupes in establishing opera as an art form across the Atlantic. Our focus on Latin America also allows for a critical assessment of the postcolonial condition of opera production in the former Spanish and Portuguese Empires. Studies on opera in the Americas, or on art in general, have always referred to European models, even nationalist approaches that were intended to give expression to notions of cultural independence. As former colonies, and even after the long process of seeking independence, these countries continued to maintain close relations with Europe, and especially with Portugal and Spain. Regarding the production of Italian opera, for a long time the repertoire, singers, composers and entire troupes came to Latin America through the Iberian Peninsula, adding their own character to ideas of operatic italianità.Footnote 19

As regards the European context, the role of Italian opera within the German-speaking lands of Central Europe represents a special case, not only due to the sheer number of theatres in the region where Italian opera was produced, but also because of the ways in which German music criticism used changing notions of italianità to articulate more general ideas about the relationship between music and national identity. Here the Habsburg monarchy is of particular interest to the study of operatic italianità, because of the Empire’s own multinational setting and its strong tradition of seeing Italian opera as a supranational art form that speaks a cosmopolitan language. It was on this basis that Italian opera came to play a leading role in supporting Austria’s supranational idea of its state.

During the nineteenth century, European musical culture became one of the issues non-European observers most frequently commented upon in the context of transcultural encounters, especially in those geographical areas where people had had very little exposure to European culture. A famous example documenting curiosity about European music are the collections of woodblock prints produced in Japan after a fleet of American warships under Commodore Matthew Perry arrived at Yokohama in 1853, forcing the Edo shogunate to open their ports to foreigners (see Figure 1.3). Many of these prints present musical instruments, and Europeans playing them in different social and political contexts.Footnote 20 Michael Facius’ chapter later in this volume (Chapter 14) shows that it took a relatively long time for Japanese society to overcome its scepticism towards Europe’s operatic tradition. When, at the beginning of the twentieth century, Rentarō Taki (瀧 廉太郎, 1879–1903) became the first Japanese person to study music in Europe, he did not go to Italy to learn about its operatic tradition, but to Leipzig. For Taki, engaging with Europe’s musical tradition mostly meant studying the piano and the lied. Within our book’s global dimension, extending our perspective from the Americas and Europe to East and South East Asia helps us to relate ideas of italianità to different concepts of Empire, but also to a more general discussion of European modernity versus non-European civilisations.

Transnationalising Opera Studies

Historians and musicologists have conventionally used national frames of analysis to explore connections between music and political-cultural meaning. In particular, music’s role in the self-perception of Italians during the nineteenth century has long informed accounts of different musical genres and of specific moments of political activism, with strong implications for the general narrative of Italy’s nation-making.Footnote 21 Because opera played a crucial role in defining Italy as a Kulturnation, the genre’s connections to nationalist discourse have often provoked controversial debate among scholars.Footnote 22

While a long tradition of scholarship accepts that music, and opera in particular, played a fundamental role in articulating Italian identity, the possible implications of the transnational movement of people, goods and ideas for notions of italianità have been largely overlooked, ignoring a significant dimension of the nineteenth-century music industry as well as of related cultural debates. For instance, few scholars have considered how the early diffusion of Italian opera in the Western hemisphere affected notions of operatic italianità, in the New World as well as back home. As early as the eighteenth century, the Spanish-born writer Stefano Arteaga, an associate of the composer and influential teacher Padre Giambattista Martini in Bologna, mentioned Pietro Metastasio as ‘the favourite author of the century, a name glorified from Cádiz to Ukraine and from Copenhagen to Brazil’, indicating the transnational appeal of the period’s most famous author of Italian libretti. When, in 1808, the Portuguese court arrived in Brazil with singers, musicians and composers, they carried with them a repertoire that even then was marked by cultural exchanges between Portugal, Italy and several other centres of European operatic life, making it difficult to assess what operatic italianità might have meant to constantly changing audiences and within different musical cultures.

By investigating the shifting meanings of operatic italianità, our collection of essays aims to take account of research that has raised critical questions over the use of ‘national opera’ as an analytical category.Footnote 23 Debates on national operatic styles often originated in the Old World. For instance, during the 1820s, critics on both sides of the Alps discussed the extent to which Rossini was influenced by German composers, contrary to a musicological tradition that has tended to use Rossini’s music to emphasise the antagonism between Italian and German musical conventions.Footnote 24 In Habsburg Europe the composer’s blending of different national styles could count in his favour, but on other occasions it was held against him.Footnote 25 During the middle decades of the nineteenth century, attempts to create German, Polish and Czech ‘national operas’ relied on compositional techniques associated with the Italian tradition, with French grand opéra or with Wagnerism, often contradicting the original aim of writing ‘national’ opera.Footnote 26 Moreover, the production of such works often relied on the involvement of musicians and impresarios versed in multiple musical styles and languages, which reflected their international careers. Despite the multi- and transnational connections of these musicians, much of the research on opera in Central Europe still focuses narrowly on tensions between German and Czech or Polish music, ignoring the huge role played by the Italian repertoire as well as the more general difficulties of distinguishing between different national idioms in music.Footnote 27 Related to this battle over operatic nationalism is the fact that many works on opera in Habsburg Europe still take a constant antagonism between opera and imperial politics for granted, without acknowledging the multinational foundations of the Empire’s idea of the state and the implications of these for its policies of cultural representation.Footnote 28 This background explains why, in addition to our focus on Latin America, several chapters in our collection of essays examine ideas of italianità as they were debated in Central Europe.

A field of research the authors of this volume took inspiration from when transnationalising their subject is Benjamin Walton’s work on the early global diffusion of Rossini’s operas, which presents a model for challenging narrowly defined national approaches in opera studies.Footnote 29 Recent work on grand opéra takes a similar approach by looking at the transnational movement of a genre that originated in a particular French operatic tradition, but then acquired new meanings due to its global appeal.Footnote 30 Both fields share a focus on transnational interactions in forming notions of music and national identity at a time when major technological developments led to an acceleration of global processes in cultural communication.Footnote 31

From a methodological point of view, many of the works that helped us to define our approach have moved away from a reading of music narrowly based on philological methods, expanding instead into the analysis of music’s wider social, economic, political and cultural contexts and its connections with public life.Footnote 32 The contributions to our collection of essays were inspired by works that foreground the cultural analysis of opera’s production, performance and reception by looking at the ways in which opera participated in the making of a modern (and increasingly globalised) public.Footnote 33 Having emerged from a close dialogue with neighbouring disciplines, in particular cultural studies, literary criticism, art history and film- and performance studies, this approach has cultural agency at its centre. Here the source base of musical research has been significantly extended: from theatre archives and materials directly related to composers, to a vast range of sources that mostly relate to the production and reception of opera, as well as to different levels of political decision-making.Footnote 34 From historical narratives focussed on particular composers and their works, many opera scholars have now turned to examining audience experiences,Footnote 35 or new spatial dimensions such as the urban, national and transnational contexts of opera production.Footnote 36 Some of these new studies pay particular attention to singers, their careers and global movements, to gender, or to the role of impresarios and their companies in challenging national readings opera.Footnote 37 Another important factor here is the building of new, often quite spectacular theatres in many different parts of the world. Through the global circulation of the repertoire and its performers these buildings retained close connections to Europe’s operatic tradition. This development meant that in addition to musicians and the repertoire, also architects, engineers and set designers travelled around the world and through their transnational movements helped to reshape national notions of opera. Finally, whenever the repertoire travelled it was also printed in new editions; and it was adapted for use in homes across the globe, via new piano reductions, as well as in public spaces, where it was performed by brass bands, street musicians or barrel organ players, all of them translating music into new contexts.Footnote 38 In all of these cases the conditions of opera production were profoundly shaped by transnational exchanges affecting musicians, composers, impresarios and audiences, as well as the repertoire they produced.

Approaching Operatic Italianità

As Susan Rutherford has argued, for much of the nineteenth century ‘music was regarded as an entirely idealised domain’.Footnote 39 Although it reflected the values and ambitions of composers and performers, and interacted with audiences, music existed in relative independence of the real world. The Gazzetta musicale di Milano argued in 1860 – notably the moment when the Italian Risorgimento had seemingly fulfilled its promise – that ‘the principal aspect of music is wholly ideal; its sphere of action that of a world let us not to say unknown, but which has nothing in common with that in which we live’.Footnote 40 The underlying aesthetic assumptions of such ideas about music, combined with the conceptual vagueness of national and ethnic identities, make it extremely difficult to connect music to notions of national character. Despite these strains, as Suzanne Aspden has argued, ‘opera’s conjoining of music and words’ challenged ‘the universalizing tendency always present in the function and power of music’.Footnote 41 Aspden gives the example of ‘Italian infiltrations’ in the music of Jean-Baptiste Lully that in the seventeenth century had prompted a discussion of the musical principles distinguishing the French and Italian peoples; debates very similar to those mentioned earlier in this introduction in relation to the distinction of operatic styles in d’Alembert and Rousseau. These tensions reflected a more general philosophical debate on the relationship between universal principles and national character that marked, for instance, Johann Gottfried Herder’s thoughts on the formation of humankind, which start from a universal notion of shared humanity in order to then explain how the specificity of conditions led to cultural differentiation.Footnote 42

What was the semantic content behind musical notions of nationality as they emerged during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries? Despite differentiating between French, German and Italian music, commentators during the eighteenth century often equated the ‘Italian’ with a cosmopolitan style, which served as contrast to a number of more narrowly defined national styles.Footnote 43 Other early theorists suggested that Italian and French styles be combined and this hybrid used to create a German one, which in turn could become ‘universal’.Footnote 44 One element here was the weight of the Italian musical diaspora leading to the idea of a more universal musical language, although the same argument could possibly be applied to the role of Bohemian musicians within a wider European context. In these debates, however, Italianness was also often associated with ‘the cheap and nasty’, an idea further complicated by the fact that many representatives of the Italian/cosmopolitan style were not Italian, but ‘imitators’ of Italian music of any national background, including, among many lesser known figures, composers such as Haydn and Mozart.Footnote 45 The prominence of some advocates of Italian cosmopolitanism notwithstanding, Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf recounts hearing Johann Christian Bach’s Catone in Utica in Parma and describing it as ‘written very sketchily, after the Italian style’; and in his Sinfonia nazionale nel gusto di cinque nazioni Dittersdorf himself satirised the fashion for the Italian manner.Footnote 46 The idea of writing music in different national idioms was in no way new. As early as 1659, Lully had integrated in his Ballet royal de la raillerie a section in which ‘la musica italiana’ and ‘la musique Françoise [sic]’ are directly juxtaposed, and in dialogue with each other: according to Aspden, this was a response to the ‘growing popular anti-Italianism’ in French culture.Footnote 47 In Rousseau’s contribution to the Querelle des Bouffons, mentioned above, the ‘citoyen de Genève’ turned these evaluations upside down, posing Italy’s supposedly natural style against French artifice. Closer to Dittersdorf’s form of musical satire, in the final act of his Viaggio à Reims (1825) Rossini parodies the same idea of national styles based on material taken from different national anthems. Carl Maria von Weber, although often associated with provoking tensions between the German and Italian schools in Dresden, considered the ability to write in different idioms an important quality. In this debate, Weber used the international success of Meyerbeer’s Italian operas as an example.Footnote 48

In similar ways, many of the nineteenth-century sources discussed in this book point to the fluidity of notions of italianità, and to the more general problem of assigning fixed meanings to opera, and to Italian opera in particular. The same has been noted by scholars outside the field of opera studies too. When Cristina Demaria and Roberta Sassatelli discuss Roland Barthes’ notion of italianicity, rather than referring to it as anything real, they see it as ‘an icon of what Italy and “things Italian” might be’.Footnote 49 Taking account of this semantic fluidity has clear implications for the validity of associating particular works with fixed political significance reflective of national character. This problem occurs, for instance, when attempting to produce ‘authentic’ stagings of particular works.Footnote 50 These semantic uncertainties notwithstanding, fluid and malleable notions of italianità continue to inform people’s reading of Italian opera independently of the time and space in which productions take place. Then as well as today, notions of italianità were informed and reinforced by musical practice and the experience of Italian opera on stage, but also by wider debates on Italian art and history; reflections on diplomatic relations and military conflict; material culture and consumption; the knowledge of classical literature; and the country’s discovery through travel writing. Although in some cases direct experience of italianità through travel or migration, and (especially during the Napoleonic period) through warfare, also contributed to creating images of Italy, most of these encounters were (and still are) filtered through complex transnational exchanges and often had no more than a loose connection with social and cultural life in the Italian peninsula.

Likewise, through most of the period here under investigation, most experiences of Italian opera did not take place in Italy, but in theatres at home, or during travel in third countries. Here, Italian works were often produced in translation, by singers of various national origins, with impresarios and casts playing on a wide range of images associated with Italy and Italian music.Footnote 51 These images reflected specific national and historical experiences, which in many cases tell us more about the viewer than about the viewed.Footnote 52 Frequently, the works performed were adapted to local conditions of musical production, which could differ considerably from those of the theatres in Italy, but counted as experiences of operatic italianità all the same. Therefore, what operatic culture stood for, north and south of the Alps, or on either side of the Atlantic, was often not the same, even at times when the Italian repertoire dominated the stages in many parts of the world. While Julian Budden associates the period from the 1850s onwards with the ‘collapse of a tradition’,Footnote 53 the ongoing success of Italian opera abroad suggests that the genre still responded to the expectations of its audiences. The famous Viennese critic Eduard Hanslick went so far as to suggest that the public felt a real need for Italian opera,Footnote 54 an impression certainly confirmed by many of the case studies this volume brings together. Therefore, the perception of operatic crisis at home, partly caused by the internationalisation of the Italian repertoire and the reckoning of ‘foreign’ influences on Italian composers,Footnote 55 often coincided with an international perception that Italian opera was still striving. By the time Hanslick was commenting on Verdi’s ongoing popularity in Vienna, the idea of a collapse of Italy’s operatic tradition had long been a popular trope in music criticism, one that almost always coincided with great acclaim of Italian opera abroad. This tale started with the fights between Gluckisti and Piccinisti in the eighteenth century, mentioned above, continued with Stendhal’s ‘narrative of decline’ to describe Rossini’s stylistic development after 1815,Footnote 56 and led to the supposed ‘end of the great tradition’ associated with Puccini’s Turandot,Footnote 57 another aspect of the same operatic crisis in which ‘un-Italian’ influences allegedly played their part.

Because of their transnational nature, junctures in the perception of operatic italianità come in many guises, which in turn left their imprint on Italian opera at home. In his contribution to this volume, Andrew Holden refers to Adriana Guarnieri Corazzol’s notion of ‘un fantastico mediterraneo alternativo’ when describing how Italians understood Giacomo Meyerbeer’s mixing of Germanic influences with Italian tradition, which in turn then left a mark on works such as Arrigo Boito’s Mefistofele. Likewise, for Thomas Mann the final scene of Verdi’s Aida was ‘ein italienischer Liebestod’, the work of a Wagnerised Italian.Footnote 58 From a musical-philological point of view, Mann might have been wrong with his analysis, but the fact that Franz Werfel, with his Verdi: Roman der Oper, turned the same tension into one of his greatest novels demonstrates the power of such images.Footnote 59 In international perceptions of Puccini’s operas the debate on foreign influences seems to work the other way round, with audiences all over the world continuing to consider the composer’s works as quintessentially Italian, despite the openness to international developments for which he was criticised by infuriated commentators at home.Footnote 60 As Emanuele Senici notes, not a single one of Puccini’s operas ‘is based on an Italian play, short story, novel, or poem’, and only Tosca and Gianni Schicchi are set in Italy; but this did not seem to affect international ideas of italianità associated with the composer’s work.Footnote 61 Many examples discussed in this volume show that italianità was not exclusively ‘made in Italy’, and that what was understood as italianità was not immune to non-Italian influences. While the argument of foreign influences shaping Italian opera is not new – as shown, in particular, by recent scholarship on Rossini and VerdiFootnote 62 – our volume goes beyond it, examining how transnational and global influences on the repertoire and its production relate to constructions of italianità in wider societal debates.

Experiencing Italian Opera: At Home and Abroad

Due to the multidimensional and often transnational nature of the world’s encounter with operatic italianità, what foreign visitors saw and heard when they went to the theatre in Italy did not necessarily compare favourably to traditions of Italian operatic culture at home. In a very similar vein, two otherwise very different French authors commented on their experience of Italian opera during their travels in the peninsula: The French composer Auguste-Louis Blondeau, a winner of the Prix de Rome, recorded detailed comments on theatres, orchestras and singers, as well as specific performances, during the four years he spent in Italy. The more famous case is the historian Hippolyte Taine, whose Voyage in Italie recalls in detail a performance of Il trovatore at the San Carlo in Naples.Footnote 63Although writing several decades apart, their disappointment over what they witnessed closely mirrors the views of the Count d’Erfeuil in Germaine de Staël’s hugely influential novel Corinne ou l’Italie, according to which ‘every French province had a better theatre than Rome’.Footnote 64 The count’s observations on Italian theatres did not necessarily reflect de Staël’s personal opinion, but stood for a view that was widespread among France’s upper classes and which de Staël was keen to dismantle. At the same time, these different literary traces show how difficult it is to make sense of these references: De Staël’s main purpose was not to talk about the quality of Italian theatres, but to depict and critique widespread French views of other nations during the Napoleonic occupation. Within the context of de Staël’s book on Italy, the count’s example reflects the fact that national ideas about musical culture often served a purpose that went beyond purely aesthetic arguments. Furthermore, since the late eighteenth century, for most foreign travellers the principal motivation behind their tours of Italy had no longer been to acquire knowledge of a foreign culture, but to search their own selves, with the result that their observations often tell us relatively little about the objects of their gaze.Footnote 65

Charles Dickens’ first mention of a musical experience in his Pictures from Italy (1844) relates to a church service in Genoa, but expresses a similarly low opinion of Italy’s musical life at the time: ‘A tenor, without any voice, sang. The band played one way, the organ played another, the singer went a third, and the unfortunate conductor banged and banged, and flourished his scroll on some principle of his own: apparently well satisfied with the whole performance. I never did hear such a discordant din.’ Playing on a well-established tradition of linking climatic conditions to national character, Dickens added – only seemingly out of context – that ‘the heat was intense all the time’.Footnote 66 The church service was not to be Dicken’s only musical disappointment in Genoa. The first theatre he went to was the ‘very splendid, commodious, and beautiful’ Carlo Felice, but he soon learned that the production was ‘second rate’.Footnote 67

Dickens is not known for his musical expertise; but when the Austrian playwright Franz Grillparzer embarked on his Italian journey, in 1819, and a little closer to the setting of de Staël’s novel, he was thoroughly familiar with the Italian as well as the German operatic repertoire, and had witnessed the first productions of Rossini’s works in Vienna. At the time, Grillparzer had just enjoyed his first European successes as a dramatist, and his writings on theatre and culture reveal great erudition as well as a complex level of aesthetic judgement. The operatic productions he saw in Venice, Florence and Rome, however, compared poorly to what he was accustomed to north of the Alps. A performance of Giovanni Pacini’s Isabella e Florange at Rome’s Teatro Tordinona, better known as the Teatro Apollo, Grillparzer described as ‘truly miserable: ordinary Italian music, poorly presented by an oversized orchestra, and mediocre or bad singers, mostly too loud’.Footnote 68 The bass reminded him of a ‘quaking frog’. He described the primadonna as ‘an arid and ugly creature’, the buffo was ‘disgusting’ and the tenor had a ‘stupid and ugly’ face.Footnote 69 The Apollo’s sets were humble, the costumes without taste, the chorus bad, the mimes miserable. The production taken as a whole struck him as poor ‘to a degree not imaginable even in the lowest provincial town in Germany’, an observation closely mirroring le Comte d’Erfeuil’s comparisons in de Staël’s Corinne.Footnote 70 A production of Rossini’s Cenerentola at Florence’s Teatro della Pergola seemed to him as insignificant as the work itself: ‘The ballet very bad, the theatre itself neither great nor pretty’, although he acknowledged the theatre’s good acoustics. Ester Mombelli’s performance was acceptable but mannered, reflecting ideas on Italian singers that were not uncommon in Viennese music criticism. His recollections openly expressed his disappointment over an art form he loved, and which he judged on the basis of his rich Viennese experience.Footnote 71

In the views of these international travellers, many of whom were familiar with the splendours of Italian opera in Vienna, London or Paris, Italy had lost much of its reputation as a musical nation, if indeed musical content had ever been central to ideas of operatic italianità. Grillparzer’s assessment of Italy’s operatic culture was further complicated by the fact that even in opera’s birthplace the best voices often originated from elsewhere: in a mediocre production of Rossini’s Barbiere di Siviglia at the Teatro S. Simone in Venice, Grillparzer was pleased to hear Joséphine Fodor-Mainvielle, at the time one of the greatest Rossinian voices, but she was a French citizen of Hungarian-Dutch descent with close connections to Russia.Footnote 72 This background notwithstanding, when a few years later the Italian impresario Domenico Barbaja engaged Fodor for the Italian opera season in Vienna, the famous chronicler Ferdinand von Seyfried praised her for being the typical example of an Italian singer.Footnote 73 Like Grillparzer, he admired her singing, but insisted that she was extremely stingy – playing on an idea the author generally associated with the representatives of Vienna’s Italian opera industry.Footnote 74 Despite the multifaceted nature of the international debate on Italian style and vocal training, discussed in Carolin Krahn’s chapter below, from a musical point of view, the Italian singers at Europe’s leading theatres were often held in the highest regard, as shown by the cults in London around the castrato Giovanni Battista Velluti; Giovanni David in 1820s Vienna, greatly admired by Metternich; or Luigi Lablache, considered ‘indispensable to the performance of Italian opera in London and Paris’ during the 1830s and 1840s.Footnote 75 As a consequence of these international movements, when Goethe’s son August visited Milan in 1830 he noted that the best singers were performing in London or Paris.Footnote 76 Meanwhile, the high quality of Italian singers abroad was instrumental to the disappointment of travellers like Grillparzer once they experienced Italian opera in Italy.

The contracted focus of operatic debate on singers’ performance also influenced evaluations of the Italian repertoire, often creating tensions between enthusiastic audiences and professional critics. As a consequence, some commentators criticised the public’s narrow interest in vocal performance for taking precedent over critically assessing the works that appeared on stage. Making use of the Kantian terminology that had recently entered musical discourseFootnote 77, the editor of Vienna’s influential Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung Friedrich August Kanne argued: ‘If until now all countries needed singers to perform operas, Italy now needs operas for the production of its singers. The means became the end, and the end the means. In turn, the drama itself was dissolved, nipping in the bud the sublime interest that moves humans to engage with the work of art!’Footnote 78 The consequences of this development for Europe’s operatic culture, in Kanne’s view, were fatal: ‘Singers started to see themselves as the main thing, turning their vocal ability in such arbitrary ways to virtuosity that no real work of art was left that would allow them to play their acrobatics to their heart’s content.’Footnote 79 Increasingly, this new cult of performance impacted productions beyond the Italian repertoire, not least because many of Italy’s international stars also performed the works of non-Italian composers, who followed the same trend. For instance, Velluti made his 1825 debut at the London King’s Theatre with Giacomo Meyerbeer’s Il crociato in Egitto – an Italian opera by a Prussian composer who was to make his later career in French grand opéra. All of these developments helped to further complicate ideas of operatic italianità – at home as well as abroad.

While the perceived mismatch between Italian vocal stardom at home and the quality of performances in Italy was one of the issues explored by foreign commentators, many travellers were also dismayed by the behaviour of Italian audiences. As Kanne’s above-mentioned argument on aesthetic ambition seems to support, in the lands where opera had been invented, going to the theatre seemed to have an altogether different meaning to that which it had at home.Footnote 80 Grillparzer criticised the Italian audience’s inattentive attitude and raucous behaviour, impressions that correspond to Lord Byron’s descriptions of the theatre in Milan.Footnote 81 Dickens wrote about the Carlo Felice: ‘Nothing impressed me so much in my visits here (which were pretty numerous) as the uncommonly hard and cruel character of the audience, who resent the slightest defect, take nothing good-humouredly, seem to be always lying in wait for an opportunity to hiss, and spare the actresses as little as the actors.’Footnote 82 Also interesting in this context is Dickens’ depiction of the Piedmontese officers at the theatre. Their behaviour seemed to mirror closely what many scholars today describe as a unique feature of theatres in ‘Austrian-occupied’ Milan or Venice, where ‘foreign’ armed forces allegedly undermined Italians’ cultural pastimes.Footnote 83 About Piedmontese-occupied Genoa, Dickens wrote: ‘There are a great number of Piedmontese Officers too, who are allowed the privilege of kicking their heels in the pit, for next to nothing: gratuitous, or cheap accommodation for these gentlemen being insisted on, by the Governor, in all public or semi-public entertainments.’Footnote 84 At least in this case it was not ‘foreign rule’ that destroyed the imaginary authenticity of Italian operatic life. Dickens also dismissed the physical appearance of many of the theatres he saw. While he found Parma a rather ‘cheerful’ town, its theatre was ‘one of the dreariest spectacles of decay that ever was seen – a grand, old, gloomy theatre, mouldering away’.Footnote 85

Orientalising or Transnationalising Italianità?

Dickens wrote within a tradition of producing travelogues that orientalised the Mediterranean in order to underline the advanced civilisation of Britain, finding great pleasure in describing the dirty, ‘God-forgotten towns’ of Italy and the picturesque habits of their inhabitants.Footnote 86 In Grillparzer’s case, on the contrary, it seems more problematic to qualify his reading of Italian culture simply as an attempt of orientalising otherness. It was principally because of his own high esteem for Italian culture that local operatic productions disappointed him. The recollections of his journeys largely lack the pejorative attitude towards Italy and its inhabitants common to other travel accounts at the time. Looking more broadly at foreign descriptions of theatrical experiences in Italy, one comes across many more positive accounts; and it seems partly a consequence of modern Italianists looking for orientalising descriptions, and giving preference to English-language accounts, that prejudiced descriptions have dominated debates in the field of (mostly anglophone) Italian studies. For instance, when August von Goethe saw Rossini’s Aureliano in Palmira at Milan’s Teatro della Canobiana, in 1830, he praised the production, including singers and sets, as well as the ballet given between the acts. He was even more enthused by his visit to the Teatro San Carlo in Naples; and in Venice he praised the productions of minor theatres, where he saw works by Cimarosa and, again, Rossini.Footnote 87 August von Goethe’s visit to Italy was very much a restaging of his father’s famous journey to the ‘lands where lemons bloom’. Also, in Grillparzer’s account, Italy does not appear as a backward South; and it shares little or nothing with a literary East. Instead, for Grillparzer Italy was ‘Hesperia’, the West, where the Austrian arrived from Europe’s Eastern periphery, after a tiresome journey through some of his beloved fatherland’s most remote provinces, including the deprived heartlands of Styria and the Slovenian mountains.Footnote 88 The huts where he spent the nights had been ‘bad and dirty, the people looked poor, with begging children running along the cart for half a mile’; almost recalling impressions other writers had left of Italy. But what Grillparzer describes here is not Italy, but Austria. Around him he notices nothing but rain and mud. The last leg of his journey before arriving in Trieste, seemed ‘a desert’, a land almost without buildings; nothing but dry chestnuts and crippled mulberry trees.Footnote 89 If in Said’s analysis ‘the Orient has helped to define Europe (or the West)’, for Grillparzer it was his own Orient that taught him to appreciate the culturally more advanced West that so many other travellers were depicting as backward.Footnote 90

After his tiresome journey through the Austrian mountains, how different then were his first impressions of Italy: ‘Finally the customs station of Optschina, a hill ahead, and yes, there it was in front of us, large and blue and shiny, this was the sea!’Footnote 91 In Grillparzer’s idea, Trieste and the Küstenland formed an inherent part of Austria’s supranational state, but it also presented the door to Italian civilisation, a concept he associated with the beauty of Venetian art, the majesty of Padua’s cathedral, and the glory of the peninsula’s ancient universities, but also with diligently cultivated plantations and the angelic beauty of the children he saw everywhere.Footnote 92 ‘No language of this world is sufficient to describe the beauty of these landscapes. … Here I wish to live and die!’, he exclaims, a phrase reminiscent of Goethe’s Wilhelm Meister, but an expression of feelings we rarely find in French or British travel accounts of the time.Footnote 93 Despite a few more mixed experiences during his journey, most of the negative stereotypes of Italians he recounted in his travel log were not of his own making but reported what Italians had told him about other Italians.Footnote 94 Even Grillparzer’s misgivings over his operatic experiences do not reflect general prejudice against Italy’s musical culture: his description of the church music at the Sistine Chapel reveals great aesthetic appreciation and deepest admiration.Footnote 95 The example of Grillparzer – one of Austria’s most influential poets at the time – demonstrates that not all criticism of Italy’s operatic culture can be reduced to another aspect of orientalising Italian culture.

Disappointment over operatic experiences in Italy suggests that opera continued to be seen, in principle, as a marker of aesthetic sophistication and of civilisation. How notions of italianità, and especially of operatic italianità were understood and employed in this sense is demonstrated by the many chapters of this volume that take a postcolonial perspective on non-European societies. The idea of opera as civilisation was especially important in Latin America. Although it often is unclear how operas were performed at the time, even for the eighteenth century its presence in the region is undisputed, supporting the idea that opera was seen as instrumental to the continent’s appropriation. Within little more than a decade of the Portuguese court’s arrival in Brazil, numerous European troupes had travelled to different parts of South America. In the 1820s two regular routes for travelling opera troupes were established in the Western hemisphere, both creating new conditions for cultural exchanges: one passing through Brazil and on to Uruguay, Argentina, Chile, Bolivia and Peru; another established between 1825 and 1827, and going back to the arrival of Manuel García’s troupe in Mexico, travelling via New York.

As a consequence of these complex itineraries, the system of operatic production also changed, with travelling troupes encountering local traditions, and some of these establishing themselves permanently or for a number of years where money was to be made, a process often accompanied by the rise of music criticism and the increased construction of opera houses. Some members of these travelling troupes later returned home, bringing with them new experiences and challenging local understandings of operatic tradition. Such troupes continued to shape ideas of operatic culture, in Italy as well as in Europe’s Eastern periphery. For local audiences it often did not matter that the works they produced had to be adapted to the specific conditions of their theatres or improvised stages, at times to the point of turning them into a distant relation of the original.Footnote 96 The nature of these adaptations notwithstanding, they show that theatre always had the potential to cross social boundaries as well as to bridge geographical distance. For instance, in his partly autobiographical novel Der Pojaz (The Bajazzo, 1893/1905), the Galician-Bukovinian writer Karl Emil Franzos tells us of a waitress who entertained the inhabitants of her native shtetl with stories of a theatre company from Czernowitz that once stayed at her inn. While the rabbi expressed a great deal of concern over possible infiltrations of worldly life in his community, the fact that, for the locals, Shakespeare became ‘Scheckspier’, and that they were unsure whether or not Schiller was still alive, did not undermine their conviction that even in the deepest provinces of the Habsburg monarchy one could take part in the Empire’s cultural life. In some cases of operatic performances, or the production of Singspiele, female roles had all of a sudden to be taken on by male singers, or vice versa, or parts of different works were combined to make for a totally new opera. What people saw was still the same repertoire that was staged in Vienna, Budapest or Milan, or so they believed.

While similar processes resulted in the rapid diffusion of opera in South America, it turned out to be more difficult in the North, as demonstrated by Lorenzo da Ponte’s attempts at establishing opera in New York, where ‘Italian language and literature were … about as well-known as Turkish or Chinese’.Footnote 97 For da Ponte this was less a comment on the difficulties he experienced when arriving from Vienna than a statement confirming that many in America seemed totally deprived of the intellectual and aesthetic benefits of Europe’s cultural heritage.Footnote 98 While da Ponte played an important role in laying the foundations of opera in the United States, financially most of his projects turned out to be disastrous. In addition to the language barrier, and moral criticism of theatre in a predominantly protestant new country, opera was often perceived as an aristocratic art form that had no place in Republican America.Footnote 99 Moreover, as Charlotte Bentley demonstrates in her chapter below, when Italian opera arrived in New Orleans and entered into competition with the local tradition of producing French grand opéra, it was associated with notions of Southern-ness rather than civilisation, showing how the semantic content of these concepts always depended on local contexts. Here as well, opera served to construct a notion of Italy abroad that, in Italy, hardly played a role.

When opera started spreading in the New World, this encounter with Italian civilisation was also reflected in works written in and for the Old World. In Joseph Haydn’s Il mondo della luna (1777), based on a popular play by the Venetian poet Carlo Goldoni, men on the moon became a metaphor for life in the New World. Another example of this genre reflecting the encounter between the Old and the New World was Alessandro Guglielmi’s La quakera spiritosa, which da Ponte had staged for Joseph II’s court theatre in Vienna and which played on gendered and religious stereotypes associated with life in the New World.Footnote 100 These works demonstrate how idealised images of American life – still rooted in Enlightenment discourse – were increasingly replaced by accounts of real-life experiences in a country that in the perspective of many of these works lacked the culture that distinguished European life, a world in which opera continued to be seen as a marker of civilisation.

As mentioned earlier, around the same time as the arrival of Italian opera in the Americas, it spread over large swathes of continental Europe, including its southern and eastern peripheries. In several parts of Central Europe the production of Italian opera dated back even earlier, to the seventeenth century, reflecting the Habsburgs’ dynastic relations with families such as the Gonzaga or the Medici.Footnote 101 At the time, this new cultural form was understood as a direct reference to the European Renaissance and Italy’s humanist tradition, which conceived of opera as the reinvention of Greek classical drama.Footnote 102 The first production of an Italian opera in Salzburg is recorded in 1614, followed by Vienna (1626), Prague (1627) and Torgau in Saxony (1627), proving those cities' affinity with Italian culture.Footnote 103 Opera’s diffusion from the early eighteenth century onwards included further regions north of the Alps, but also the Balkans, which geographically were not far removed from Italian shores and were connected to Italy via the urban centres of the Venetian Republic.Footnote 104 In the 1730s, Pietro and Angelo Mignotti produced works of opera in Prague and Brünn/Brno, as well as in Laibach/Ljubljana, later expanding into many other parts of the continent.Footnote 105 Over the centuries, Italian opera in Central Europe came to reflect the political ideas that informed the Habsburgs’ supranational and cosmopolitan concept of state, which meant that its production counted for much more than the national tradition of one of the monarchy’s many nationalities. Aspects of this association with cosmopolitanism marked operatic italianità over centuries and across continents, with Italian being perceived as the natural language of music and opera. As Dina Gusejnova has argued, cosmopolitanism – whether operatic or philosophical – offers a sense of certainty during periods of change and conflict, which is why Italian opera becomes an important key to our understanding of the Napoleonic and post-Napoleonic age, an argument brilliantly exposed in Emanuele Senici’s Music in the Present Tense.Footnote 106 At the same time, acknowledging cosmopolitanism’s conceptual vagueness and its inability to establish eternal peace is not to dismiss it altogether, but to question its promise of heuristic certainty. Orlando Figes sees operatic culture as foundational to the emergence of a new European identity during an age of nationalism and railways, reaching from the Atlantic shores to Russia and beyond.Footnote 107

Returning once more to Grillparzer’s experience of operatic italianità, his account shows that even during the early decades of the nineteenth century the concept was a construct that existed more or less independently of the culture a music-loving traveller might encounter in Italy. The operatic productions he saw in Italy reminded the author of the ritualistic gestures he witnessed during the church services at St Peter in Rome or the performance of miracles by the priests of San Gennaro in Naples.Footnote 108 To Grillparzer, the productions he saw seemed deprived of the aesthetic truth he associated with the excellent dramatic art he knew from home or elsewhere in Europe, which was at the origin of his admiration for Tasso and Italian classicism, for Shakespeare and Cervantes. Grillparzer had similarly disappointing experiences when comparing Canova’s cold sculptures with the allegedly more authentic classicism of the Dane Bertel Thorvaldsen, whose workshop he visited in Rome. For the same reason, Byron chose Thorvaldsen to sit for a portrait head.Footnote 109 Had transnationalism led to a development where foreigners had become the better Italians?

De Staël and Ideas of Italianità in the Age of Napoleon

Grillparzer’s descriptions of Italian landscape shared much with scenes from Germaine de Staël’s Corinne, or Italy, mentioned above. Few commentators of the early nineteenth century enjoyed greater influence in debates on national character than Germaine de Staël, and her impact on Stendhal, and on his discussion of Rossini, has often been pointed out.Footnote 110 If in recent years, Italianists have tended to look to de Staël for evidence of orientalising Italians’ allegedly effeminate and indolent character, they underestimate both the contextual dimension of her work and the intellectual weight of her political thought.Footnote 111 Further to her aim of writing a novel, de Staël also went to Italy with the aim of studying the legacies of political institutions that contrasted with France’s centralised tradition of state; the latter had been introduced in Italy by Napoleon, as part of what she perceived as the Emperor’s antiliberal dictatorship.Footnote 112 Read as speech acts in the drama of international relations during the Napoleonic Wars, the intention behind De l’Allemagne and Corinne was only partially to speak about Germany and Italy, with de Staël’s main challenge being directed at French and British politics, as well as at respective societal conventions in both countries, and how they affected Europe as a whole.Footnote 113 Her open rejection of Italy’s fossilised classicism was in fact intended as a reference to the neoclassical aesthetics of Imperial France, and of what Napoleon made of Rome’s artistic heritage, which she contrasts with Italians’ true but suppressed aesthetic potential. This complex constellation explains why no one objected more violently to Corinne than the French Emperor, who even during his exile was still irritated that she had not used her novel to praise the supposedly revitalising impact of his campaign on Italians: ‘Not a word about me’, he howled.Footnote 114

De Staël’s keen interest in the connection between collective passions and aesthetics generates a transnational perspective on notions of italianità that is directly relevant to the methodological framework behind our book. Ideas for Corinne, or Italy in fact predated her Italian journey, going back to her stay in Weimar, in 1804, where most of her hosts were closely familiar with Italian arts.Footnote 115 It serves as another example of the complex transnational dimensions influencing constructions of italianità. The idealised concept of German romanticism de Staël explored during those months in Weimar, subsequently recorded in De l’Allemagne, is set against the aesthetic conventions of Imperial France, but it also responds directly to Europe’s romance of Italy that had developed out of the cultural practice of the Grand Tour. While some contemporaries denied that de Staël had taste in the visual arts,Footnote 116 she regularly entertained her acquaintances at the piano and impressed them with the declamation of classical drama.Footnote 117 Although opera did not play a major role during her conversations in Weimar, it allegedly was an opera she saw there – the Singspiel Die Saalnixe by Ferdinand Kauer – that made her decide to explore the political, social and aesthetic interdependencies informing Italians’ national character.Footnote 118 Kauer’s opera tells the story of a nymph abandoned by her knightly lover for a mortal, a plot best known in its later version of Antonín Dvořák’s Rusalka. In her novel, de Staël’s character Corinne takes the role of the nymph, but also carries clear features of the author’s own personality: a strong and independent character of true sentiments, suppressed by foreign domination.Footnote 119 In de Staël’s account, foreign intrusion is not so much a matter of physical power but of spiritual hegemony exercised through the application of cultural and social norms that de Staël associates with France’s domination of Europe, but also with Britain’s attempts at building an informal empire in the Mediterranean. Her analysis, therefore, needs to be read as part of her work as a political thinker, and as one of the most eloquent critics of Napoleon’s imperial system. It therefore cannot be reduced to the orientalising prejudice against the allegedly effeminate Italian character that most recent commentators have extracted from her novel.

For de Staël, aesthetic sensitivity directly reflects social and cultural attitudes. In Corinne she juxtaposes Italy’s creative abilities with the restrictive conventions commanding social relations in Northern Europe, now imposed on the peninsula by France, but also by Britain. While her hatred for Napoleon is well known, and reflected in the novel’s depiction of a society under siege through its focus on Corinne’s lover Oswald, Italy is also set against England, a country de Staël otherwise admired for its political institutions. England is depicted as puritanical, lifeless and repressive of individuality, and as hostile to women in particular. In this way, England serves de Staël as a canvas to develop her idea of female freedom, which she invented as a character trait of Italy, contrasting it with the paternalistic structures of English aristocratic society, as well as with the patriarchal submission she associated with Napoleonic France.Footnote 120

De Staël’s transnational approach to the analysis of collective behaviour has largely been overlooked by critics of her Italian gazes. While she considered individuals to be emotionally too different for their behaviour to be predicted, she believed in recurrent patterns of collective behaviour.Footnote 121 As she explained in De l’Allemagne (1810), ‘national character has its influence on the literature; the literature and the philosophy on the religion; and the whole taken together can only make each distinct part properly intelligible’.Footnote 122 At the same time, de Staël was known for her sensitive approach when pursuing her experiments on collective emotions, carefully amalgamating foreign cultures into her own realm of transnational experiences and cosmopolitan ideals. In this, her attitude could not be more different from that of Byron, who spent most of his time in Italy quarrelling with the Shelleys and other expats, confirming to himself stereotypes of Italians that had been circulating among the British upper classes for generations.Footnote 123 As the Weimar-based antiquarian and literary critique Karl August Böttiger reports, de Staël ‘does not just ask, she also listens carefully; she not only hears her own voice but is serious about internalising other opinions and judgments. … In doing so she becomes a midwife of foreign ideas, which she then knows to sense and to develop in all their complexity.’Footnote 124 Reflecting de Staël’s earlier work on the influence of passions on individual and collective happiness, the basis of her art was, in Böttiger’s words, the ‘abandon de soi même’, which allowed her to amalgamate a multitude of different ideas and cultures into new forms.Footnote 125 Spiritual renewal was what she expected from these transnational exchanges.Footnote 126

The Italy she invents in Corinne is characterised by exactly such patterns. She describes Italy, and especially its port cities, as a melting pot of different peoples and cultures, where ‘spirit and imagination find pleasure in the differences that characterise the nations’; at the same time, ‘the art of civilisation will always tend to assimilate humankind’.Footnote 127 Nationality, in de Staël’s account, therefore does not describe fixed categories, but malleable entities where culture and the arts – understood as civilisation – play a central role in shaping social and political institutions. The outcome of her exploration of national character, therefore, is not an exercise in national stereotyping but a transnational examination of collective identities that uses one national character to speak about another. As a matter of fact, the purpose of Corinne, or Italy is as much to talk about the British (Oswald) and the French (Count d’Erfeuil) as to talk about Italians (Corinne, who partly stands for herself). When de Staël describes the social and cultural conventions of Corinne’s Italy, she points her finger at the countries that hold Italy at bay to impose their own values: in France ‘society is everything’ and in London ‘political interests absorb almost all others’, she concludes in Book 1 of Corinne.Footnote 128 In contrast to the French and the English, Italians retain their true character through ‘the arts’. In this, unfortunately, they ‘are far more remarkable for what they have been and for what they could be, than for what they are now’.Footnote 129 These circumstances notwithstanding, the Italians national character is, for de Staël, more profound than the version of it that is portrayed in the present.

Stendhal’s subsequent depictions of Italy lack the philosophical grounding of de Staël’s studies, but distinguish in similar ways between the Italy that presents itself to the author and the idealised image he explores in defining different aesthetic and social categories. According to Dominique Fernandez, Stendhal’s image of Italian attitudes reveals ‘a profound contradiction between the Italy that thinks and exists, and the Italy Stendhal wanted her to be’.Footnote 130 While Stendhal shares with de Staël the purpose of contrasting Italian with French social attitudes, the principal interest behind his work on opera is to establish the complex relationship between Rossini’s style and his musical debt to Mozart and Haydn,Footnote 131 understood as contrasting forms of musical practice: ‘In the northern countries, of twenty pretty girls who are taught music, nineteen study the piano. Only one is shown how to sing whereas the other nineteen end up appreciating beauty solely in what is difficult. In Italy, the entire world seeks to achieve musical beauty through the voice.’Footnote 132 Here he plays on a theme de Staël had developed in almost exactly the same words: ‘Instrumental music is as generally cultivated throughout Germany as vocal music in Italy. Nature has done more in this respect, as in many others, for Italy, than for Germany; for instrumental music labour is necessary, while a southern sky is enough to create a beautiful voice.’Footnote 133 It is these images that impacted nineteenth-century notions of operatic italianità.

With two English translations in the first year of its publication,Footnote 134 de Staël’s Corinne became a European bestseller. While opera scholarship often relies heavily on the testimony of male agents – documents generated by impresarios, and music criticism in newspapers and musical periodicals – de Staël’s prominent role in the discussions of collective passions and aesthetics also helps to diversify our perspective on the connection between music and national character. Not least because of the close association between music, romance and sexuality in early-nineteenth-century debates on opera, it would be misleading not to take gender, sexuality and interpersonal affection into account when analysing discourse on that musical form. As Susan Rutherford has argued, ‘the relationship between love and music was nowhere more evident than in opera’, and one might want to add ‘in Italian opera’.Footnote 135 Her argument that ‘it was passion that engendered music as much as the music itself expressed passion’ sums up a debate that leads us from Rousseau’s above-mentioned contributions to the Querelle des Bouffons all the way to Stendhal’s engagement with de Staël’s observations on Italian, French, English and German character.

Further complicating the analysis and deconstruction of notions of italianità, Rutherford also points out that especially ‘Verdi appeared less conscious or less persuaded – of the supposed indispensability of amorous passion to opera’.Footnote 136 For instance, neither Nabucco nor Macbeth included romantic elements, and only his domestic dramas of the 1850s, especially La traviata, began to focus more closely on romantic sentiment.Footnote 137 While these later works certainly count as Italian treatments of the theme of love and sexuality, geographically and musically these operas also breathe a good deal of foreign air and therefore further confuse our ideas of operatic italianità.Footnote 138

Globalising Italian Opera

The chapters following this introduction are arranged in roughly chronological order, taking readers on a journey that had started in Italy, but then moved from Europe to the Americas and on to South East and East Asia, with several return journeys in between, not dissimilar to the itineraries of the opera companies that are at the centre of our narrative.

Fernando Berçot’s chapter investigates the life of an Italian opera company in Rio de Janeiro after the arrival, as a consequence of the Napoleonic Wars, of the Portuguese court in Brazil. During the 1820s the local press assumed a central role in negotiating the relationship between these artists and their new audiences, revealing a growing public interest in opera and its protagonists that at the same time was reflective of shifting notions of national and social identities. Carolin Krahn examines ideas of Italian national character in Nina d’Aubigny von Engelbrunner’s influential pedagogical work Briefe an Natalie über den Gesang, which was first published in Leipzig in 1803 and marked transnational debates on Italian vocal style for several decades. Francesco Milella’s chapter looks at the role of Italian opera in negotiating Mexico’s postcolonial identity. As a case study, he examines the stay of the famous Spanish tenor and composer Manuel García in Mexico City during the years 1827–9. Claudio Vellutini argues for the role of Italian opera in asserting the supranational identity of the Habsburg monarchy during the reign of Emperor Ferdinand I, when impresario Bartolomeo Merelli was able to consolidate Gaetano Donizetti’s position in Vienna. Not German Singspiel, but Italian opera was at the core of the Habsburg’s cultural policies during the years leading up to the revolutions of 1848.

Charlotte Bentley’s chapter brings us back across the Atlantic to investigate the changing fortunes of Italian opera in the Americas. Her chapter looks at the competition between French and Italian opera in New Orleans during the years 1837–43, and the role of the city’s operatic connections with Cuba, revealing new and different notions of Southern-ness. José Manuel Izquierdo König analyses the experiences of Italian opera singers in Chile, Peru, Bolivia and Ecuador in the 1840s, a time when opera was central to the local construction of ideas about liberalism, Europeanism, cosmopolitanism, and the all-encompassing notion of ‘civilisation’.

With Arnold Jacobshagen’s chapter our volume moves into the second half of the nineteenth century. He reads obituaries of Gioachino Rossini in the French, English and German language press as transnational narratives of Italian opera, reflecting the tremendous international media response generated by the composer’s death, but also the continuing role of music theatre in articulating notions of transnational and national identity. The decades between Rossini’s death and the outbreak of World War I saw opera in Italy absorb multiple literary and musical influences from beyond the Alps, challenging the essence of what audiences and critics believed Italian opera was all about. Andrew Holden’s chapter examines this process, with special focus on how references to religious life in opera reflected changing notions of italianità during a time when Italian opera was increasingly influenced by international operatic forms, including grand opéra and Wagnerism. Similar experiences of cultural exchanges and the transformation of the operatic repertoire determined Teresa Carreño’s 1887 attempt to launch an Italian opera company in Caracas, which ended in dismal failure. Ditlev Rindom’s chapter uses this example to examine the problematic status of Italian opera’s ‘civilising’ ambitions for local Venezuelan elites.

Rashna Darius Nicholson moves our transnational perspectives on operatic italianità to colonial Bombay and South East Asia, where from the mid-nineteenth-century residents were exposed to Italian opera, intermixed with different forms of European and American music theatre, and with a whole range of local musical traditions, including African elements. Companies involved in these entertainments travelled as far as China, Japan and Australia. The chapter then traces Parsi theatre’s role in the creation of a modern South Asian ‘aural culture’ through the indigenisation of Italian opera. An Indian brand of opera that combined European melodies with Hindustani music became a staple not only of the theatre but also of the cinematic medium that followed. In a study based on the German reception of Alberto Franchetti’s Germania and Ruggero Leoncavallo’s Der Roland von Berlin, Richard Erkens raises questions about the difficult relationships between operatic style, exoticism and national identity. Franchetti and Leoncavallo, although heavily influenced by Wagnerism, employed the language of operatic italianità to represent German national and dynastic myths on stage. Despite the popularity of Italian opera in Germany, both works were met with remarkable levels of hostility, including direct criticism of the German Emperor and his operatic policies. Rosie McMahon investigates ideas of operatic italianità at the Teatro Amazonas during the belle époque and probes the extent to which the opera house became a means of engaging in a ‘global fantasy of civilisation’. The final chapter, by Michael Facius, examines the search for operatic italianità in early-twentieth-century Japan. During the two decades between the first Japanese staging of Gluck’s Orpheus in 1903 and the end of the Asakusa opera in the great fire of 1923, musical theatre in Japan saw a rapid process of adoption and transformation of operatic forms. Despite the well-known role of Italian choreographer Giovanni Vittorio Rosi in producing Western opera at the Imperial Theatre in Tokyo, the association between opera and Italy – so prominent in other parts of the world – never quite took hold in Japan. The chapter thus interrogates the limited appeal of italianità in the history of transnational operatic encounters, rooted in the difficulties of transplanting a composite cultural form to foreign settings.

Finally, Benjamin Walton’s epilogue to this volume provides a critical reflection on the wider outcomes of our project for operatic italianità in a global and transnational context.