In descriptions of the love triangle murders, Xuemei’s husband never puts in an appearance. When I asked about him, the answers I got from residents of Ox Horn were always vague and ran along the lines of: “He was a fisherman”; “The fishing in Matsu wasn’t good, so he moved to Keelung (Taiwan).” Is the absence and silence of this fisherman husband connected in any way to the difficulties of the military period in Matsu?

Restricted Fishing and Imagination

Beginning with the establishment of the WZA, the proportion of the population involved in the fishing economy steadily declined (J. Wang Reference Wang2000: 165–6), with many fishing villages emptied out by emigration to Taiwan. Most of the Matsu people who moved to Taiwan came from fishing villages such as Beigan’s Qinbi and Qiaozi, Nangan’s Ox Horn and Jinsha, and Juguang’s Fuzheng and Tian’ao (S. Cao Reference Cao1978). Indeed, the implementation of military rule had a tremendous effect on the fishing economy, such that fishermen could no longer make a living. After Matsu was militarized, the unrestricted movement of fishermen on the seas was deemed a threat to national security; fishermen were seen as “internal enemies” and potential leakers of military secrets. The state started to implement a series of stringent rules and inspections to reduce any potential threat.1 The procedure was as follows: anyone wanting to work in the fishing economy was required to apply to the village administrative office. Each applicant needed to supply three guarantors and was required to pass a clearance check before he could receive a fishing license.2 A licensed fisherman had to register with the village administrative office the day before he wanted to go fishing and receive a day permit. Before he set out, the fisherman had to show his fishing license and permit to the port authorities and pass an inspection before the guards would return his oars (for sampans) or motor starter (for motorboats). Every fishing trip had to have at least three people, and the boat was required to return with the same personnel onboard (Z. Chen Reference Chen2013: 80). These layers of onerous restrictions served to control fishing on and off the water.

Military officials worried that once at sea, Matsu fishermen could come into contact with fishermen from enemy territory and leak military secrets, so they established fishing boundaries that could not be crossed. In addition to being assigned a serial number, fishing vessels were required to fly an official flag so as to be more easily monitored. If fishermen crossed over a boundary or were suspected of fishing outside the allowed zone, upon return they would be restricted from going out again for at least a week, face interrogation and sometimes torture, be subject to jail time, and could even be banned from the water for extended periods. When any boat returned to harbor, the port authorities would inspect it for contraband and again impound the oars or motor.

Given the enormous maritime area, however, there were necessarily sporadic gaps in military control and surveillance. Matsu fishermen had a keen sense of where they could go at sea to avoid the eyes of soldiers, and where they could have contact with fishermen from the other side of the Strait: “Sometimes, when the weather was good, we’d run into them and hide someplace we couldn’t be seen to chat. But when we came back, we wouldn’t dare talk about it…otherwise we’d be locked up!”3

Matsu and mainland fishermen behaved like old friends when together, conversing congenially, joking and laughing with each other. They shared a mutual understanding, and did not participate in the enmity between the KMT and the CCP:

The policy of shelling only on odd-numbered days [Chapter 2] was more about propaganda than it was about harming people…And we’d shelled them before too. We fishermen didn’t have any issues with each other. We’d bump into them and chat like friends, but we wouldn’t say anything about it when we went home. We’d talk about ordinary stuff, never about the shelling or anything like that. They’d also tell us how their families were, how their lives were going, how well they were eating…They told us, “Your army is really strict with you out on the sea.” The Chinese fishermen could go out to sea for several days without fear and return whenever they liked, but we had to come back at the end of each day. They’d also say, “If you can get away, we’ll take you out for a few days of fun.” The war was being waged by the governments, while we’d just treat each other like friends.4

Sometimes, however, the friendliness of the mainland fishermen would cause problems for the Matsu fishermen.

The soldiers were afraid we’d have contact with fishermen from China, but they couldn’t watch us all the time! Once when I went out, they brought a bag of peanuts and we ate them together on the boat. There was so little time to eat! When we came back, we dumped them all overboard! It’d be illegal to bring them back with us. They brought a big bag to give to us, but we said we’d just take a handful. They didn’t know we couldn’t bring it back with us, and they told us to just leave it on the boat and have some whenever we wanted it. But if it were found, we’d be in serious trouble. Fishing is nothing but suffering!5

In this unique space on the water, the fishermen could temporarily escape military control and imagine they were still connected with the other side. On the ocean they found freedom and friendship, and shared small pleasures, but this space and imagination was always hidden, momentary, and evanescent. “Fishing is nothing but suffering!” (F. thoai ia siuai) was a cry heard from fishermen throughout the wartime period.

Indeed, if a vessel was even suspected of coming into contact with an enemy boat, military officials could easily impound the boat for days, but not going out to sea had a huge effect on the fishermen’s livelihood. In an interview with me, a fisherman from Tieban sorrowfully recounted:

My brother was suspected of having contact with the other side and was punished by not being allowed to go out for a week. In order to make a living, after a few days he secretly set off from the other end of the harbor. He never came back.

Matsu Daily even recorded an order from the WZA chair demanding that fishermen gather at the Temple of Goddess Mazu to take an oath:

Yesterday at the Tianhou Temple, the fishermen of Nangan took an oath not to circumvent regulations. The vows were overseen by the WZA chair and were taken by 310 people. …At the meeting, Wu Muken, the executive manager of the Fishing Association, took a public oath on behalf of his members, and led everyone in pronouncing this oath: I swear to Goddess Mazu that I will respect the rules and regulations of the fishing zone, not leak secrets, and have no contact with enemy boats or anyone else at sea. If I violate this vow, I will submit to the punishments of both military law and Goddess Mazu: may I never bring home another catch, may my boat overturn, and may I die at sea.6

For 300 people whose entire livelihoods depended on fishing to condemn themselves before Goddess Mazu to never bringing home any fish or to dying in a disaster shows that there was considerable coercion behind the taking of this oath. There can be no doubt that it was made under duress.

Clock-in Clock-out Fishermen

Among the multiple layers of rules controlling the time that fishermen could spend at sea, it was the restriction of permitted hours of fishing which dealt the greatest blow to their livelihoods. Military authorities did not allow fishing at night: in the summer, boats could set out at 6 am and had to return by 7 pm; in the winter, the hours were from 4:30 am to 6:30 pm. However, many factors, including the variety of fish, the tides, weather, and routes were difficult to control and affected the timing of the boats. Delay in returning was the most frequent problem for fishermen. One of them said:

The rules dictated what time you had to be back in port. The truth is that they were worried about us going to the mainland. If you came back one hour late, they’d keep you from going out for a week. They didn’t even care about tides. Sometimes I’d come back at six, but could only enter [the harbor] at eight, because of the tide. They didn’t know anything about tides, they’d just interrogate you, “Where’d you get off to…”7

Fishermen from Ox Horn alluded to similar problems. The former village head told me: “It was often impossible to come back on time. If we got delayed, we’d give our biggest catch of the day to the harbor guard and beg him to let us back in.”

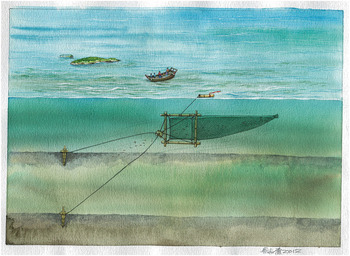

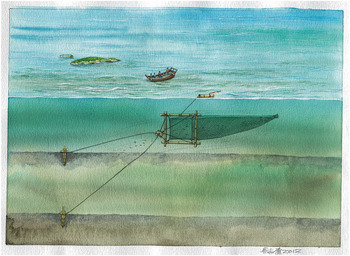

Controlling the hours of access to the harbors had the serious effect of limiting the number of times fishermen—in particular, the local shrimpers—could put their nets in the water. Cao Yaping’s (Reference Cao2017) research meticulously describes the close relationship between the fluctuations of the tides and the shrimp industry. The tidal range between the high water of high tide and the ebbing of low tide was particularly extreme in the ocean surrounding Matsu, and fishermen frequently used fixed nets to capture their most important catch, namely shrimp. Each day brought two cycles of high and low tides, and fishermen would calculate the timing before going out to gather shrimp. As one fisherman explained:

[We’d] go out at the peak of high tide and the lowest point of low tide. …We’d stop for an hour at each. Stopping for an hour when the tidal waters weren’t moving made things much easier. The fixed nets needed to take advantage of that quiet moment on the sea, and we’d have to put the nets out and bring them back in within an hour.8

The fishermen said that when the tides weren’t moving, the nets would naturally float to the ocean surface, and that was when it was easiest to collect shrimp. If they didn’t pull the nets in promptly, the shrimp would suffocate and rot in the sun. But with the military restrictions in place, fishermen could only go out during the daytime. Where they used to bring in the nets four times a day, they now could only bring them in twice, seriously limiting their working time at sea. When I interviewed the highly experienced Tieban fisherman Chen Qizao, he told me that the rules restricted their time considerably. Fishermen often didn’t have time to bring their nets in properly, and when the water was high, the nets would easily tear, causing significant losses.

The army disallowing fishing at night not only reduced the daytime catch, it also presented an even bigger obstacle for fishermen who specialized in the kinds of fish, such as ribbonfish, that were caught at night. Some of these fishermen had no choice but to switch their speciality and invest in new fishing equipment. Fisherman Cao Qijie said: “Ribbonfish can only be caught at night…but later because of communist bandits…we couldn’t go out at night, and the fishermen all started to switch to shrimp fishing, which meant they had to buy new equipment. Most of us had to go into further debt when we hadn’t even paid off our old debts.”9

The purchase of fishing equipment and tackle presented another important dilemma for fishermen. In the past, the materials that fishermen needed to make their equipment, such as bamboo fiber and rice straw for rope, bamboo stalks, and wood, were all purchased on the mainland. A few months before the fishing season, they would begin to make their equipment: fishing rope, stakes, buoys, fishing nets, and so on. Approximately two months before the start of the season, fishermen would drive stakes into the seabed, which they used to anchor their nets when the fish arrived. (Z. Chen Reference Chen2013: 50–3, 85–6) (Fig. 3.1).

In the past, maintenance of the boats and equipment relied on the mainland, but after relations between China and Taiwan were severed, fishermen could only turn to Taiwan. Taiwan is much farther from Matsu than the mainland, and conditions in the Taiwan Strait are dangerous and highly unpredictable; thus fishing supplies rarely arrived on time. After the WZA came into effect in 1956, fishermen faced serious difficulties for two successive years while there was no regularly scheduled movement of cargo ships between Taiwan and Matsu (J. Lin Reference Lin2013a). By that time, fishermen had already taken out large loans that they had no way of repaying. Matsu Daily recorded similar struggles that recurred year after year:

This year the needed shrimping equipment has not reached the islands, preventing fishermen from putting out their nets.10

Due to a delay in delivery of fishing supplies, fishermen have suffered more than 3 million [Taiwan dollars] in losses.11

[Fishing] materials are scarce, transport is difficult, and because of related delays, fishermen frequently suffer significant losses.12

The shrimp season has begun two months early…but fishermen do not yet have their equipment.13

This year, bamboo has been slow to arrive, affecting the timing of the net staking.14

In addition to the lack of supplies, the export and sale of fish also became an issue. In the past, Matsu fishermen could efficiently ship their goods to Fuzhou. With the imposition of military rule, transportation and labor expenses rose precipitously; there was also insufficient cold storage. As a result, fishermen could only sell their catch to soldiers on the island or to dried fish vendors. Even in times of a bumper harvest, the market was extremely limited. Fishermen were forced to borrow from the government or depend on unreliable government aid year after year. Flipping through Matsu Daily, it becomes clear that poverty among fishermen in the 1960s and 1970s was widespread.

The WZA Chair has indicated that loans will be granted to the fishing industry and distributed among needy fishermen in the area.15

The WZA Chair has indicated that loans will be granted to needy fishermen before the lunar new year, in amounts between 500 and 1000 yuan per net.16

Before the lunar new year, the WZA Chair distributed a total of 130,000 jin of rice to fishermen, in loans of 100 jin per shrimping net, which can be returned interest-free after the fishing season.17

In the lean times before the shrimp season, loans of 36,000 jin of rice were given out.18

The shrimp season has ended with a total haul of 700,000 jin…with an average of nearly 500 jin per net. After expenses for equipment are deducted, fishermen face difficult times.19

With losses in the fishing industry over the two past years, fishing villages are on the brink of collapse.20

Uncertain supply lines, the harsh new rules imposed on the fishing economy, and the limited opportunities to sell their catch sent Matsu fishing villages spiraling into poverty, forcing them to rely on government aid. And what about the fishermen themselves and their families? A construction contractor in Ox Horn provided the most poignant image of their suffering:

My dad died when I was ten. But I still remember seeing him smoking in bed late at night, looking dejected. At that time there were a lot of restrictions on fishing: what time you had to leave, what time you had to come back—and none of it corresponded with the tides. And every time he saw the guards with their loaded guns, he’d feel even worse.

When I returned from Matsu to Taipei in 2008, I went to see Guan Quanfu, who was born in 1920 (and passed away in 2016). People in Matsu told me that he had a lot of experience in the fishing economy. As chairman of the Fishing Association around 1960, he would be a useful source of information. Guan Quanfu had long since moved to Taipei, and when he heard that I wanted to ask him questions about the fishing economy, he immediately exclaimed: “The government…didn’t understand anything!” I asked him why, and he answered:

Without the government, we could fish freely. When the army arrived, it nearly killed us. Before they came, people in Matsu did fishing and many ships came from Lianjiang on the mainland to buy the better fish. The leftover fish would be bought by other villagers to be sold to the northern part of Fujian. At that time, small fish were preserved with salt and alum, and tasted really salty and bitter, but it kept them from turning soft and going bad. We weren’t used to eating it, but the “northern natives” liked to eat that kind of fish. They lived in a place with so much fog, their faces “looked blue.” If they didn’t have that salty bitter fish to eat, they wouldn’t be able to take it. They would come to Fu’an and trade bundles of wood [for the fish]. People on Matsu made cooking fires with cogon grass and leaves, which burned quickly. Wood would burn longer.

Curious, I asked him where the salt and alum came from. He replied:

It came from the north. We used our own boats to go purchase it or trade for it. If we didn’t have any rice, we could trade sweet potatoes for it. When the army arrived, they made us leave and come back at certain times, so how could we fish? The fish are most plentiful at night!

Mr. Guan described a more lucrative system of exchange between fishermen on the southern islands and those living in the mountains of Fujian (indigenous peoples). This system was completely disrupted when the army arrived, and in order to survive, many islanders had no choice but to leave the islands.

“Carrying all their Possessions on a Pole to Taiwan”

Toward the end of the 1960s, Matsu people began to emigrate to Taiwan in large numbers. According to statistics, the population of Matsu was highest in 1970, at around 17,000 people. From that point on, people began to leave, and the population reached a low of 5,500 people around 1990 when military rule was abolished (Qiu and He Reference Qiu, He and Liu2014:16–18). Over twenty years, emigration reduced the population of Matsu by two-thirds. Why did so many people leave? Liu Hongwen’s (Reference Liu2017) The History of the Emigration of Matsu Villagers to Taoyuan informs us that whether it was an individual or a family that moved, the reason was the same: “There’s no way to live on Matsu; there’s no hope there” (F. mo leinguah, mo hiuong). This was why so many “carried all their possessions on a pole to Taiwan” (F. suoh ba piengtang tang suoh kaui kho teiuang).

There were many reasons why people from Matsu left for Taiwan. Although Matsu did not experience any actual battles, it was under constant threat. In the twenty-one years between 1958 and 1979, the “one day on, one day off” shelling from China led to many injuries and deaths and kept people in a state of constant terror. For Hu Shuiguan, who now lives in Bade, Taoyuan, the scars run deep. He lost his left leg in a bombing of the Matsu movie theater (located at the army recreation center) in 1969, and watched his youngest son die in front of him. His eldest son Hu Zongwei was sitting in another part of the theater and escaped this catastrophe. Hu Zongwei recounts:

After my father got injured, he fell into despair because of the death of my little brother. Since the shelling happened [at an entertainment facility], it wasn’t covered under the ordinances of the Ministry of Defense regulating pensions given for work injuries. Not only did he not receive any compensation, he also lost his job as the village office assistant because of his disability. He tried to eke out a living by opening a little grocery store and learned photography so he could open a studio. But he always lived under the shadow of the bombing, getting nervous on odd-numbered days, and becoming terrified at the sound of artillery shells overhead. In 1969, my father couldn’t take the unending torment any more and decided to move the family across the sea to Taiwan.21

Born in the same village as Hu Shuiguan, Zhang Yiyu was a construction worker who also worried about his family’s safety. After watching family after family leave, he moved his own to Taiwan as well.

The other reason people left was the shrinking fishing economy. As described, under the WZA fishing had become an increasingly arduous way of earning a living. In order to survive, many fishermen moved to Taiwan. As Chen Hanguang puts it:

In 1968, I saw how difficult it was to make a living by fishing. I agreed to sell off my equipment and nets for NT$3,000, but the buyer ran away after paying me only NT$1,000. I took that money and set off on the long, uncertain road to Taiwan.22

Chen Deyu, who tried to modernize his fishing technique by buying a modern pair-trawler with a government loan, also ended up moving to Taiwan. He recounts:

Around 1983, the government offered loans to fishermen to buy motorized pair-trawlers. Together with twelve other fishermen, we bought two boats…and began to use them to fish. We worked together for more than a year, but our partnership still dissolved. It wasn’t because our catch was insufficient, but because of an imbalance between supply and demand. When we had a good catch, we couldn’t manage to sell it all, even at a low price. We didn’t have cold storage at that time, and the local market was limited. The fresh fish couldn’t make it to Taiwan.23

In the early 1960s as the fishing economy contracted, people began to move to Keelung, the major port in northern Taiwan, to work as fishermen. Others moved to Taipei County (today’s New Taipei City) and largely ended up working as street vendors and laborers. The area that received the most immigrants was Bade in Taoyuan (74). Why was it able to accept such a large number of immigrants?

The Emigrants’ New Home

Looking at the area as a whole, Taoyuan County is a key industrial and manufacturing center in northern Taiwan. Several industrial zones are clustered there, and people from across the island came to find work during the early stages of Taiwan’s industrialization (see also W. Lin Reference Lin2015: 107–10). Later, foreign laborers were also drawn to the area, such that today the neighborhood around the railway station in Taoyuan is replete with Southeast Asian stores, creating a multinational mix of businesses and people (Z. Wang Reference Wang2006: 105).

Today’s Bade City in Taoyuan County was once known as Bakuaicuo (lit. “Eight Houses”) and became Bade only in 1949. It was once a farming area, but with the industrialization of Taiwan in the 1970s, the government began establishing industrial zones in Taoyuan (L. Lin Reference Lin2007: 112), and many factories were set up in Bade since there was a considerable amount of land there. By 1976, industry had already surpassed agriculture as the primary economic activity in Bade. As of 1988, nearly 60 percent of the people there were employed in this sector, of which the three main industries were the manufacturing of machinery, electronic components, and textiles (Z. Liao Reference Liao2008: 110–1). These flourishing industries meant ample employment opportunities, allowing more people to move to the area. The result of this rapid increase in population was that Bade was upgraded directly from a township (xiang) to a city (shi) in 1995, skipping the intermediate stage of town (zhen) entirely (W. Lin Reference Lin2015: 109) (Map 3.1).

Map 3.1 Bade in Taoyuan County

The opportunities provided by Bade’s busy industrial area encouraged many Matsu people to settle there. Some came because of family members, some based on the recommendation of neighbors or friends. They found work making textiles or clothing, or took all sorts of positions in steel mills, plastics plants, and tableware factories. The boss of the Lianfu Clothing Factory was a man from Fuzhou, and many of the immigrants from Matsu ended up taking jobs there after they heard his familiar Fuzhou dialect.

However, owing to the differences between the languages and cultures of Matsu and Taiwan, the people who settled in Taoyuan had a hard time adjusting at first. The Fuzhou dialect being their mother tongue, those from Matsu usually spoke heavily accented Mandarin. They did not speak or were largely unable to understand the Hokkien dialect popular in Taiwan, and so were alienated from the mainstream culture. When they spoke in their dialect to each other, however, they would speak volubly (from their habit of speaking loudly in their native island valleys), and their loud incomprehensible voices could give Taoyuan locals the impression of arrogance and aggression. Zhang Xiangfu, who worked in the Lianfu factory from the early 1970s until his retirement, told me:

At that time, the Bade hoodlums looked down on us and would throw their beer bottles into our factory. Sometimes they’d take sticks and watermelon knives and charge into the factory to find a Matsu person to beat up. The factory had to hire a local guard to sit in front of the entrance every day. When we went to the factory or got off our shifts, we’d always go in a group. We’d try our best to stick together.

Gradually, Matsu immigrants gathered in an area near the factories called Danan. A street there is named “Matsu Street,” with many stores selling traditional Matsu products. More such stores, selling all sorts of goods from Matsu, are located near the main market in Danan.

In general, however, those who emigrated to Taiwan are happy with their decision, despite the hardships they faced. For example, Liu Meizhu, an early immigrant says:

At that time, there were lots of people from Matsu working for the Lianfu Company. We worked long days, from 8 am to 9 pm, almost every single day. When we first arrived in Taiwan, we were grateful to Lianfu for giving us a chance to work. My mother said that with a job cutting threads in the Lianfu factory, you had air conditioning and could sit as you worked, and sometimes you could even chat a bit. Back in Matsu you had to work out in the wind and rain or under the scorching sun, and in the winter the cold would get into your bones, and you had to fight the others for water. …It was much easier working for Lianfu. Above all, if you worked your regular job, and did some overtime, you could earn at least NT$10,000 yuan a month. If you had three people in the family earning that much, that was NT$30,000–40,000 a month in income. You could save more than NT$20,000 each month, and in two years you’d have the money to buy yourself a little single-story house.24

Beside the regular salaries, the people of Matsu often mentioned that the rice in Taiwan wasn’t the rationed rice they were used to, and that it tasted much better. Fowl was also cheaper and tastier than at home. The bright lights, new electronics, sturdy pavement, shiny tiles, and so on, all made them feel as though their lives had improved both spiritually and materially (H. Liu Reference Liu2017: 83).

Yet they still missed Matsu. They invited their deities to Danan, set up branch statues, and finally built the Longshan Temple (1970) and the Mintai Temple (1974). Every year, they held traditional Matsu festivities for the Lantern Festival, and established the Matsu Association to maintain their connections with their hometowns. In 2018, they even went so far as to build in Bade an exact duplicate of a Longshan temple from Ox Horn in Matsu.

Guaranteed Admission Program

As the fishing economy declined and fishermen emigrated, a new social category began to appear in Matsu: teachers and civil servants. Before 1949, education in Matsu relied primarily upon private teaching. Teachers were employed from the mainland to teach the traditional classics. At that time, most of the population was impoverished, and only those from relatively well-off families could afford to go to school, with a fraction of those wealthier students going on to middle or high schools (Y. Chen Reference Chen1999). Take Ox Horn as an example: the well-to-do Chen Lianzhu studied on the mainland and thus spoke Mandarin well. Under the WZA, he was a cultural and linguistic bridge between the military and the locals, and later he became the chairman of the Matsu Association of Commerce (S. Li et al. Reference Li2014).

When the army came to Matsu and discovered widespread illiteracy on the islands, they aimed for an ideal situation of “one village, one school” (yi cun yi xuexiao) and established elementary schools across the islands (J. Lin Reference Lin2013b). At that time, Matsu had no middle schools; once children finished elementary school, the best students were sent to Jinmen to continue their studies. With the implementation of the WZA in 1956, the first middle school on Matsu was built in 1957 and was intended to help improve the general educational level. The school was immediately faced with a shortage of teachers and its graduates with a lack of opportunities for further study. Of the very few teachers on the islands, most were soldiers from the mainland. When older Matsu people speak of their teachers, they frequently say: “The teachers at that time were all soldiers, they taught both Chinese and English.” To address the shortage of teachers, the WZA established the guaranteed admission program.

The guaranteed admission program was designed to help Matsu students go to Taiwan to study, guaranteeing them a tuition-free place without having to participate in the national test. The first year of Matsu middle-school graduates in 1960 numbered forty-eight, of whom twenty were sent to junior normal universities, as well as farming, fishery, business, and nursing schools.25 When they finished their studies, they were required to return to Matsu to serve as elementary school teachers or to work in county government organizations for at least two years. With the opening of Matsu’s first high school in 1968, a series of students were sent to Taiwan via the guaranteed admission program. There was also another program designed to improve the quality of teaching. The returning teachers could apply and go to Taiwan again to study in normal universities (Guan Reference Guan2008), after which they could qualify to teach in middle or high schools.

Overall, these programs gradually produced a new category of educated people in Matsu, which superseded traditional family and lineage influences, and the dominance of those who had studied on the mainland. These people had a tremendous impact on Matsu, particularly after the dismantlement of the WZA, as will be discussed in detail in Part III of this book. Still, even during the WZA rule, we can see the effect of their return to villages and their assumption of teaching posts or positions in local government. Students of farming or maritime vocational schools could work in farming or fishing associations, or for agricultural development centers. Graduates of business schools could return to work in local government accounting bureaus. In this way, a new social category of teachers and government employees gradually arose in Matsu.

Even those who had only graduated from local elementary schools also began to have opportunities to work in local government organizations. They frequently worked at the lowest levels, responsible for the general administration of various offices with meager but secure wages. However, they could take the ad hoc civil service examination (quanding kaoshi) designed by the WZA to obtain further qualifications and slowly climb up the career ladder.

The Rise of the “Boss Lady”

By 1970, many from Matsu had moved to Taiwan, but some decided to remain behind. I asked those who remained why they stayed, and they replied along the following lines:

I didn’t have any relatives in Taiwan, and I didn’t have the money to move. On Matsu I could grow vegetables and run a small business.

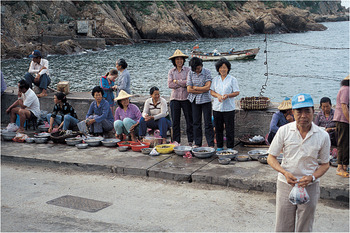

Indeed, at that time many Matsu people knew no one in Taiwan and had no practical way of moving there. At home, at least they could grow and sell vegetables, or sell fish and shellfish to soldiers. They describe this way of earning a living—doing “G. I. Joe business” (a’bing’ge shengyi) (Szonyi Reference Szonyi2008: 134)—as “supporting a family with one scale” (F. suoh ba tsheing yong lo suoh tshuo noeyng). Many businesses, such as snack and drinkstands, small grocery stores, billiard rooms, barbers, laundry services, public bathhouses, tailoring for uniforms, etc., arose to serve the needs of soldiers.

These businesses were frequently run by wives (Fig. 3.2). A woman from Shanlong who once ran a snack stand told me:

At that time, we had to take care of our elderly parents and children, but my husband only made NT$700 or 800 a month. It wasn’t enough to live on.

Not only did the wives of low earners and fishermen begin working, it was also common to see wives of high-level government workers opening stores that catered to soldiers. For example, while the former county commissioner Cao Changshun was the principal of Jieshou middle school, his wife ran a shop selling stationery and Western medicine in Shanlong. Further, the wife of the chair of the County Council sold breakfast in the market for decades before retiring only a few years ago. Almost every woman participated in these businesses. A woman from Ox Horn who grew vegetables and went each day to Shanlong to sell them recounts:

My husband was a fisherman and he often lost money on it. So I grew whatever I could sell. That was the only way our family could survive.

Matsu was traditionally a fishing society, in which the men went out to fish and the women stayed at home to look after the family. They grew sweet potatoes, took care of animals, gathered firewood in the mountains, and did all kinds of household labor. Their husbands would frequently not return for days at a time (especially when they had gone to the mainland), and accidents at sea were common, so the wives or mothers of fishermen were often solely responsible for their households. As I mentioned earlier, Matsu has a saying: “A wife/mother is the hoop around the bucket” (F. lauma/nuongne sei thoeynɡkhu)—in other words, the wife or mother is the force binding the whole family together.

Nevertheless, it is indisputable that the status of women is low in most fishing societies. In the past, Matsu women primarily provided household labor, and since they could not go out to sea to fish like men, they were not able to make money for the family. Earning money being “a man’s work,” many elders said that men would apply this very rude phrase to curse their “disobedient” wives for their inability to earn even a cent: “Even if women pissed oil, men would still have to carry it to market!” (F. tsynoeyng niu na pienglau iu, toungmuonoeynɡ tang kho ma)

These traditional gender relations changed demonstrably under the WZA with the influx of soldiers and their consumer demands. Fisherman Liu Mujin says:

Men rarely went to sell things at market. The soldiers wanted to buy from women. They’d only do business with them.

Women could carry things in to sell at the barracks. If a man approached the barracks carrying something, the soldiers would block his way. But they wouldn’t stop women. Once they sang out a peddler’s cry, the soldiers would all come out to buy.

As we can see, in the military economy, women could go to the market early in the morning and sell vegetables or fish. Later in the day, they could go to the barracks to sell things or take the soldiers’ dirty clothes home to wash. They could also work in shops, or even open their own. Under the WZA, women not only took care of their households but also conducted business. They interacted with the soldiers and became an important source of income for their families.

Younger women even became a conduit to military goods for their families. People often said that coveted tickets for ships headed to Taiwan could be easily procured if a family had a daughter. H. Liu’s article (Reference Liu2016) of “Carrying Swill” describes how the older sister of his childhood companion drew the attention of military officers because of her good looks. At that time, most families on Matsu raised pigs, and everyone wanted to fatten them up by getting swill from the military camps. Not only did his pretty sister obtain swill for them, her whole family had steamed buns and meat to eat because of her connection to the soldiers. Eventually, she reluctantly married an officer around the same age as her father.

Young or pretty women could easily attract the attention of the soldiers or become objects of unwanted attention or even assault. Previous studies have shown how women become targets of sexual violence during times of war (Das Reference Das2008; Kelly Reference Kelly, Jacobs, Jacobson and Marchbank2000; Sanford, Stefatos, and Salvi eds. Reference Sanford, Stefatos and Salvi2016, to name only a few). For this reason, Xuemei, of the love triangle murders I described in Chapter 2, is rarely criticized by villagers. In fact, they usually sympathize with her for the difficulties she faced as an indigent fisherman’s wife. As Cao Daming commented while showing me the murder trail, “she may have been a bit open to other men, but what other options did she have?”

Despite the difficulties they faced, women under the WZA came to have new opportunities: they participated in the market economy, and gradually identified themselves with their businesses. The “boss lady” (laoban niang) was undoubtedly a significant female identity that came to prominence during the war era. For example, in the army there was a popular song called “My Home is on the mainland” (wode jia zai dalu shang) which described the homesickness felt by those soldiers who had followed the KMT government to Taiwan in 1949. The original lyrics began:

In Matsu, these lyrics were changed by the soldiers to:

“Boss Lady and Her Business” became a way for soldiers to sing about their feelings and attachments, above and beyond their longing for the motherland.

Women who worked outside of the home at this time also began to form their own business associations, such as the “Thirteen Golden Hairpins” (shisan jinchai) of the Shanlong market. The Thirteen Golden Hairpins was by no means the earliest market organization—the “Fourteen Brothers and Sisters” (shisi xiongmei) already existed—but it was the energy of these new women members that first attracted greater attention, and soon such sister groups began to gain popularity across Matsu.

The members of the Thirteen Golden Hairpins were women who sold vegetables, fish, dried goods, and frozen foods inside the Shanlong market, and ran breakfast stands, bakeries, and small groceries outside the market. In the beginning there were thirteen women, but the number gradually increased to fifteen. They set out together as businesswomen from a young age, grew up, and married all around the same time. Maintaining frequent interactions, they gradually became a solid community. I asked them at what point they had sworn sisterhood with each other, and they said: “We’ve been together from the beginning. It was probably thirty or forty years ago, at some festival when we put on two feasts together, that we formally declared ourselves sisters.”26

They saw each other every day at the market, and whenever one had an important event such as a wedding or funeral, they would all join in to help. After their economic situation stabilized, they learned dance together, sang karaoke, played cards, and even now, in their old age, still travel together. One local man said:

In the past, if women sang or danced, they’d be called loose or flirtatious (F. ia hyo ia tshiang). But the Fifteen Golden Hairpin women learned how to sing and dance.

As their old dance teacher pointed out:

The Fifteen Golden Hairpin women might have learned how to sing and dance, but when a temple festival came around, they would all make food, beat the clappers, and help carry the goddess’s palanquin. At other times, they would help clean up the village. They “took the lead” (F. tsau thau leing) in such things.

The local temple recognized their impact and named the head of their organization to an honorary post at the temple, circumventing a vote by the all-male temple council. The WZA chair also took notice of their importance, and would formally invite them to dine with him, even including them in his New Year’s celebrations.

These women always speak of their work spiritedly. For instance, the “squad leader” (banzhang) of the Fifteen Golden Hairpins told me proudly:

Men can only do one thing at a time, but women can take care of a lot simultaneously.

When I asked them why it was that women had to undergo the most hardship, the second Hairpin, whom people called erjie (second eldest sister), spoke passionately:

A woman’s work is her “career (shiye)”; it’s her source of support and her responsibility. Sometimes a husband doesn’t make much and has to rely on his wife. Matsu people have a saying: “The big stones make the wall, and the small ones fill in the holes” (F. tuɑi luoh lieh tshuo, sa suoh tai). …You have to see the old houses on Matsu to understand. The stones here are all oddly shaped instead of having smooth surfaces. So when you built a house, you couldn’t just use big stones; you had to fill in the holes with smaller stones in order to keep the walls from just falling down. The small stones are key!

The second Hairpin clearly pointed out that a woman’s business during the military period was her “career,” having importance both for herself and for her family. She also used the metaphor of the small stones to suggest that although women might be physically smaller than men, they held an important part of the responsibility for keeping their families going. Her self-confidence is obvious. Matsu women like the compliment of being called “capable” (F. ia puong nëü), indicating that they are competent, skillful, and able. To call a wife or a mother “capable” is to praise her ability to run a household: able to give orders, delegate work, and turn a profit. Nearly every Matsu woman was a skillful budgeter and could adjust her business to meet the needs of the soldiers. Any money they made was invested in local money-loan associations. When it reached a certain amount, it would be used to purchase property for their children in Taiwan (or also Fuzhou after martial law was lifted). As their economic contribution increased, so too did their status.

Influenced by the Fifteen Golden Hairpins, women across Matsu began to organize. Not only did the women on the snack street in Matsu Village (located on the western side of Nangan Island) organize into the “Twelve Sisters” (shier jiemei), but the women of Ox Horn also formed the “Sorority of Twelve.” The mothers of Ox Horn danced together, played the clappers in rituals, and got involved in local matters. In fact, I once went with them to clean up the seashore, and saw how they helped collect ocean detritus. The Sorority of Twelve, however, was in some ways distinct from the Golden Hairpins of Shanlong or the Twelve Sisters of Matsu (village). Most of the Sorority worked not at their own businesses but in government kitchens or at the Matsu distillery, either as laborers or as service workers. The reason for this was likely connected to the love triangle crime described in Chapter 2. After the murders took place, Ox Horn was declared a “restricted zone” (jinqu), and the roads into the village were stationed with guards who prevented soldiers from entering. The decline of the fishing economy was already a blow to this fishing village, and things worsened once it was declared a restricted zone. The stores of the earlier business area, Da’ao (Big Inlet), had to shut, and many of those who wanted to do business opened shops in the market at Shanlong, the neighboring village. The former village head told me that when the government decided to establish a market on the island, the people of Ox Horn pushed hard to be chosen as the site. But because the village did not have enough space, the market went to Shanlong instead. The laborious and menial jobs, taken of necessity by the Sorority of Twelve, demonstrate the deterioration of this village’s economy.

In Shanlong in 2009, I met Cao Xiaofen, the “boss lady” of a florist’s shop (I shall discuss her further in Chapter 7). Like many women on Matsu, after graduating from elementary school, she worked as a clerk at a bookstore in Shanlong and ended up marrying a man from the area. Her husband’s family raised chickens and ran a restaurant, and she was kept very busy each day helping with the work. As the G. I. Joe business became increasingly competitive, she left Matsu in 1976 to work in a clothing factory in Bade, Taiwan. When her husband took ill, he went to Taiwan for treatment; she took care of him and engaged in some minor business to support her family. After her husband died, she had the chance to study floriculture, which she enjoyed, but unfortunately her son fell ill. After many years of toil, she herself was diagnosed with cancer. With the help of her family back in Matsu, she returned home to recover. Having gone from Matsu to Taiwan and back again, she shared her observations with me:

When I returned to Shanlong a decade ago, I realized that the women here had changed! They sing and dance and play cards—they’re more active than the women in Taiwan!

Returning to Matsu helped her recover from her illness, and inspired by her friends, she opened a flower shop with a café and taught floriculture. The media reported that she had “returned to her hometown to finally live for herself” (J. Liu Reference Liu2004c). Even today, we can see vigorous boss ladies arriving at the markets early to buy ingredients for their restaurants catering to Matsu’s burgeoning tourism. There are also some female graduates from high school or college who have formed cultural organizations and participate actively in Matsu society nowadays.

Conclusion: Men and Women during the War Period

During the WZA period, the fishing economy in Matsu confronted severe challenges. As Taiwan began the process of industrialization in the 1970s and required a greater labor force, many Matsu locals moved there—mostly to Taoyuan—to work in factories. Those who stayed behind on the islands shifted their forms of livelihood to offering services and goods to the military. The guaranteed admission program and obligation to return home to work also introduced a new social category of government employees and teachers to Matsu. They would come to exert a tremendous influence on the future of Matsu, as I will discuss in Chapters 8–10.

Under the WZA, women also faced circumstances utterly different from those seen in the past. In the fishing society, men had made the primary contribution to the family finances by going out to sea, while women, who maintained the household, held a lower social status and were offered few educational opportunities. The military economy, however, opened up new possibilities for women. The G. I. Joe businesses, as Szonyi (Reference Szonyi2008:140) pointed out, were part of the militarization of the war period; female labor in Matsu was mobilized, as it was in Jinmen, to provide goods and services to soldiers. However, the changes the women of Matsu experienced differed from those in Jinmen. On the one hand, the new role of women, as in Jinmen, did not subvert traditional patrilineal ideology: the members of the Fifteen Hairpins were mothers first and foremost. They did not try to usurp the position of their husbands as head of the household, nor did they show great enthusiasm for temple politics. On the other hand, their role as boss ladies and their brisk business with the army gave them different possibilities outside of the patrilineal authority. The Fifteen Hairpins not only challenged the traditional Matsu view that singing and dancing were for “loose women,” their collective power even induced the elders and military leaders within the patrilineal society to acknowledge their contributions. Finally, they were given their own honorary posts in the temple without being subject to a vote by the all-male temple council. These differences from the women in Jinmen are related to the islands’ differing histories: the lineage organizations on Matsu were never as strong as on Jinmen, given Matsu’s long history as a temporary stopover for fishermen.

In many ways, the development of the women of Matsu was more along the lines of the Taiwanese or mainland model of the “female entrepreneur.” Gates (Reference Gates and Perry1996, Reference Gates1999) describes how petty capitalism offered women, both in Taiwan and in the mainland, more autonomy and social power. Simon (Reference Simon2004) also points out that in Taiwan, boss ladies often stressed that their businesses endowed them with free space in which to live. Not only could they contribute to the family income, they could also go beyond their household and develop new connections with the larger society. Under the WZA, the lives of the women of Matsu were in important ways different from the earlier days.