Part III explores a pivotal transitional period for Matsu. As the army left and the islands gradually opened up to the world, both individuals and the island society faced a new situation. Chapter 7 follows the women of Matsu and the struggles they faced—between marriage and self, family and work, Matsu and Taiwan— through the late military period into the present day.

In Chapter 3, I discussed the changes that women experienced from the fishing period into the era of military rule. When fishing was the main source of household income, men were valued more highly than women, who had very few opportunities to receive formal education. Although elementary schools, and later some middle schools, were built across the islands under the WZA, most women who finished primary school promptly began to conduct G. I. Joe business to earn money for their parents’ families. After marriage, their earnings went towards supporting their husbands’ families. Although women’s ability to engage in petty commerce and to contribute economically raised their status both at home and in the larger society (as shown in Chapter 4), their lives continued to revolve closely around the family. As a Matsu saying goes: “When the mother is there, the family is complete; when the mother isn’t there, the family falls apart” (F. noeyng ne duoli, suo tshuo iengnongnong. noeyng ne namo, tshuo tsiu sang lo). A woman was the protector of her family, supporting its very existence, and sacrificing herself for it.

During the late military period, however, some women began to take their lives in different directions. Although women of this period were not afforded the advantages that men had access to, such as receiving government-guaranteed education in Taiwan, many of them left for Taiwan in search of jobs to support their families financially. Others went to Taiwan to study, if their families allowed it. Their experiences in Taiwan had a huge impact on their later lives. This chapter examines the new struggles that women confronted. I take three women, born between 1950 and 1980, who lived through the era of military rule and beyond, to discuss the rise of a new female self and the changing meanings of contemporary family and marriage. Rather than representing Matsu women in general, their unique experiences provide crucial insight into the changes in women’s conceptions of themselves and the challenges that contemporary Matsu society faces today.

Rising from Floriculture

Xiaofen is one of the most elegant women in Matsu. Her clothing always exhibits a unique style, and she has meticulously turned the first floor of her home into a café. Still, my most lasting impression of her is from 2008, during a pilgrimage to China. She planned it as a reunion for her siblings’ families. The line of several dozen people in a pilgrimage procession was quite an eye-catching sight.

Cao Xiaofen was born in 1956 and is the eldest of seven children. In order to help share the burden of supporting the family, soon after graduating from elementary school she began to work at a bookstore in Shanlong as an assistant. She says that she always loved to study, and even used the money she earned from her first job to go back to middle school for a semester, returning to work only when she ran out of money. At the impressionable age of eighteen, a matchmaker arranged for her to marry into the Chen family in Shanlong. At that time, her husband’s family had opened a restaurant catering to the military, doing both G. I. Joe business and raising chickens at the same time. Xiaofen was expected to help with all of it, and that kept her extremely busy.

As G. I. Joe business became more and more competitive, the family had to find other ways of making ends meet. In 1976, Xiaofen’s mother-in-law arranged for her to leave Matsu for Taiwan, and so she arrived, pregnant, in the Bade district of Taiwan to work in the Lianfu Clothing Factory. At that time, means of communication and travel between Matsu and Taiwan were quite limited, and she had few chances to see her husband. He would occasionally come to visit her, and each time he prepared to leave again, she felt heartbroken and hoped that the ships between the Keelung harbor and Matsu would not set sail. Tragically, not long after her child was born, her husband fell ill with uremia. Since Matsu is fairly remote, and a lack of medical knowledge delayed his care even further, her husband had to spend many years on dialysis in Taiwan. When her husband got sick, Xiaofen left her work at the clothing factory and moved to Taipei to take care of him. Burdened by medical expenses, and with very little education and no professional training, she could only engage in manual labor to make money. In the winter she sold cakes in a market, and iced drinks in the summer at the hospital gates in order to supplement the family income. She says that one day after work she was pulling her cart home and heard someone behind her calling, “Mister, Mister!” and she realized with surprise that her skin had darkened from being out in the sun year round, and her appearance was indistinguishable from that of a man (J. Liu Reference Liu2004c).

When her husband passed away in 1991, she finally had a moment to catch her breath, and she decided to take classes in floriculture. She said:

I had a chance to study flower arrangement, and it was like I was back in primary school and could remember how happy studying makes me!

After many years of toil, however, she was diagnosed with cancer in 2000. During her treatment, the illness and the suppression of her emotions over many years of caring for the family led to depression. She stopped working in the market for nearly half a year, and this period of rest gave her a chance to reconsider her own life. She realized that the tense relationship with her mother-in-law had caused her to become servile and obedient. Because she was forced to take care of her husband, mother-in-law, and child who were all frequently ill, she found herself suffering from low self-esteem and had gradually begun to cut ties with people. After her own illness, her siblings and elementary school classmates wanted her to come back to her childhood village, Ox Horn, to recover, so she moved in with one of her younger sisters. An old classmate, Cao Yixiong, was promoting “Village Conservation” (see Chapter 8) at that time. He often came to visit, providing emotional support by taking her on walks to show her how the village had been transformed and renewed. He encouraged her to develop her artistic talents and to move back to Matsu for good to open a flower shop and a café in a historic building in the village. With the support of friends, Xiaofen gradually returned to health, and she decided to go back to Taiwan to learn to become a barista before returning to Matsu to open a café. She did not imagine that her flower shop would eventually do brisk business, and that her classes in flower arranging would prove to be very popular. Today, she is often invited to other islands to give lessons at women’s associations and community centers. She said: “Floriculture helped me find my ‘self,’ and it also made me realize that Matsu is the place I’ll always come back to.” With her new chance at life, she is not only a florist, but now also plays the role of the central figure of “eldest sister” in her family. She arranges family events at specific times over the year, which helps to solidify and maintain their familial relationships:

The place where I’m living now is the “family home” (niangjia) for my brothers and sisters. Each year, I organize a family reunion and we all go traveling together. My sisters and I also have a separate get-together, and it helps us all stay close.

When her florist’s business does well and she makes some extra money, she sends it to her son in Taiwan.

Over the past little while, I’ve done a pretty good business, so I’ve sent NTD$500,000 to my son and his wife in Taiwan. They have several children, so their financial situation is tight.

Xiaofen’s case is particularly dramatic. After arriving in Taiwan, she suffered greatly from her illness, yet over the course of her sickness and recovery, she also managed to gradually free herself, slowly recognizing how severely she had been constrained by the traditional mother-in-law/daughter-in-law relationship. A succession of family misfortunes caused her to withdraw even further, until eventually she was diagnosed with cancer and was confined to her own tiny world. Then, allowed the opportunity to study floriculture and to develop her talents, she was able to achieve a new selfhood. With the emotional support and practical aid of her family and former classmates in Matsu, she was able to recover from her illness, and now she has also established herself as the center of two different families. She not only serves as a bridge between her brothers and sisters, but also helps support the younger generation of her own family in Taiwan.

Torn Between 0 and 9

Xiufang loves to chat with us, but she only appears in the late evenings. Each time, she says: “I’m running around all day, and I can finally relax when I’m chatting with you.” But she can’t stay for too long, or her husband will call and urge her to come home.

Li Xiufang has a very busy job as an accountant. At 8 am each morning, she starts her day rushing back and forth between two different government agencies. She gets off at 6 pm and must hurry to the hostel that her mother-in-law runs to help keep the accounts. After dinner, she frequently goes back to the office, finishing up at 10 pm. She has been working in Matsu for twenty-one years, and these long days happen at least once a week and more often three times a week. She is transferred to a new government agency every four years and has already held positions in twelve different agencies.

Although she is kept very busy, when Xiufang speaks of her work, she always has a smile and a look of pride on her face. With her circumspect manner and her natural aptitude for numbers, she is often able to help her colleagues deal with the most complicated write-offs. When she is able to handle some thorny numbers, she says she always feels “a great sense of accomplishment!” Still, her demanding work reduces the amount of time she can spend with her family, and she reveals a sense of regret about her children. I asked her why she had chosen to work as an accountant, and she told me:

Because my dad’s family had no money, he didn’t have the chance to continue his education. He felt like he’d really missed out, so he always placed a lot of importance on our education. When I graduated from middle school, my dad sent the whole family to Taiwan so we could study there. When I was small, my mother washed clothes, tailored uniforms for soldiers, sewed military insignias, sold seaweed, working herself to the bone to make money. When we went to Taiwan, she came along to look after us and sold dumplings to help support the family. When I got into a business college, my dad encouraged me to get a degree.

After graduation, Xiufang got a job as an accountant in a government office. She married a man from Matsu, returned there for work, and had two children. Her husband also works in a government organization, and they are typical of many families in Matsu in which both husband and wife work for the government and enjoy a very stable lifestyle. Her husband makes allowances for her busy job, which often prevents her from coming home on time. He is the one who makes dinner and looks after the children. Xiufang is responsible for all of the cleaning, and in this way, the two cooperate in the running of the household.

When Xiufang speaks of her family, she often emphasizes that she is able to give her children ample time and space in which they can focus on their studies. This relates to Xiufang’s own difficult experiences going to school in Taiwan as a teenager. Moving from a remote island to a metropolis, Xiufang was packed into a small apartment with her five siblings as well as five cousins to study and sleep together. She says that at the time, she did not have her own desk or her own bed. When she got home from school, she would have to make dumplings until late at night, and because of this, she tried her best to stay at school to study until 9 pm before returning home. Now, she is proud that she can offer her children their own personal space in which to grow up and develop.

Because of her hectic schedule, however, Xiufang has no time to cook for her children, and that is a source of deep regret for her. In Matsu, one very important traditional role that mothers play is to cook for the family. The meal that a mother prepares represents a maternal role that many Matsu people recall with deep emotion. Li Jinmei, who served for twenty-five years on the county legislature in Matsu County, says that during the time she was engaged in politics, she would come home each day at 5 pm to cook for her family, and only after they had eaten together would she return to her meetings. Today, we find a vibrant scene of married working women returning to their mothers’ houses to eat dinner. Xiufang’s family also often goes over to her mother’s house to eat dinner. From this we can also see that for women in Matsu today, although their sense of self is indissociable from their work, they still identify strongly with the traditional role of the mother as the center of the household. The emotional intimacy fostered by a mother cooking dinner for the family and bringing everyone together is still irreplaceable for Xiufang in terms of how she views herself as a woman. For this reason, although she considers her career and her professional capabilities to be significant accomplishments, she still feels guilty about not being able to come home to cook for her children every night. As a contemporary woman, she is torn between striving for professional success and fulfilling the traditional role of the mother.

In Search of a Common Vision

Every time Lihong goes out, she’s always meticulously made up. Her hair smells sweet, because she always washes her hair before she meets with us. Her eyebrows are carefully plucked, and her face is rosy and full. She puts on eye-catching necklaces, bracelets, and other jewelry, and even when she’s in a tracksuit, she always shows her own sense of style.

Chen Lihong was born in 1971, one of five siblings, the youngest of whom is a boy. She recounted:

I’m the second oldest in my family, and my older sister and I both got good grades. But we were not well-off, so she and I decided not to go on with our schooling after graduating from high school, and instead to help make some money for the family so our younger siblings would have an easier time of it.

I asked her what she and her sister did to help. She told me they did all kinds of jobs, but that she was especially good at “carrying water” (taishui), and that she would collect nearly all of the water that the family used. Back when Matsu did not have running water, the water used by a household would be collected from wells and carried back to the home. She said:

I could carry a lot of water! In elementary school, I used to go with my sister. Then in middle school I would do it alone, and I’d hurry back from school each day to help out. The first gift my dad ever gave me was a stainless-steel water pail specially ordered from Taiwan. It’s still there in my parents’ house.

We can readily sense Lihong’s satisfaction about the help she was able to give her family. In fact, like Xiufang, Lihong could have gone to Taiwan to study after high school, but she decided to stay so that the money could go towards the education of her younger brother. Years later, on his wedding invitation, he specially thanked her and her older sister, “and when I saw that, all of it [the sacrifice] was worth it,” she told me with tears in her eyes.

Although both Lihong and Xiaofen sacrificed themselves to help their families and in particular their younger siblings, the former is different from the latter in that she grew up during the late period of the WZA. Lihong’s family engaged in many different kinds of G. I. Joe businesses, including selling breakfast foods and snacks, and running a karaoke bar. As a girl, she would keep watch over the karaoke bar as she studied, and so had contact with the military from a young age. She told me that early on the soldiers would fight over her affections, and not a few of them tried to ingratiate themselves with her. “Were you ever interested?” I asked her. “I can’t say I never was,” she responded. However, one of her aunts had married a soldier, and after she went with him when he was posted to Taiwan, their marriage suffered. Because of this, Lihong felt that it was safer to marry a man from Matsu, with whom she would have a greater chance of having a secure life and a harmonious marriage. Doing chores and helping out the family as a girl, she had already started to develop her own ideas about the future.

After she grew up, she chose a local Matsu man with a steady income from among her many admirers. Her husband worked for the government, and she was also employed by the government at the time on contract, so together the two of them had a healthy income. After they married, they soon bought a house and a car, and a year later had a baby. Just as their life together seemed to only be getting better, her husband took up gambling, and then began to have an affair. Lihong said:

When I found out that he’d been having an affair and I argued with him about it, he told me that I shouldn’t poke my nose into what he did outside the home. He wanted me to be a traditional wife and stay at home. As long as I took care of the family, everything was fine.

Lihong could not accept her husband’s attitudes, and once he had been unfaithful she allowed herself to become emotionally detached from their marriage. She worked even harder to make money, so that she could prove to the court that she had the economic means to take care of her son, hoping to be granted custody of him. She became licensed as a nurse’s aid in order to get a better job with a steady salary. Still, since her husband could provide a better home environment, she agreed to allow her son to continue to live with him. She arranged a set time to come visit him and to take him out to do something fun. After her divorce, Lihong did not move back to her parents’ house, as was traditionally expected of women, but instead rented a room, wanting her own private space in which to live. Each time we met, she would always be carefully dressed and made up. She felt that after her divorce, she needed to keep up her appearance, to make herself feel better than she had before. She told me: “Many women realize only after they get divorced that they have a lot of capabilities. The struggle for survival brings out latent potential.”

Like many traditional women in Matsu, Lihong has sacrificed for her family since she was a young child. In the process, however, she has also slowly been developing herself: she planned out the kind of marriage and family that she wanted, and made it happen. Despite all of her careful planning, her marriage unfortunately ended in divorce, but she described the outcome this way:

My husband and I struggled for a long time to build the kind of family that we had. But as soon as we had everything we’d been working for so hard, we lost sight of a common goal for the future.

Lihong’s reflections reveal that she did understand that her husband’s leaving might also have been caused by his pursuit of “another kind of self [beyond the family]”: it was precisely because husband and wife lost their common vision that their marriage failed and their home life collapsed. In any case, Lihong is no longer willing to submit to a man’s demands, as women had done in the past. Her decisions demonstrate how different contemporary Matsu matrimony is from the traditional model. In the past, as long as men brought money home to support the family, they were free to gamble in their spare time; even affairs were tolerated by their wives. But Lihong and most of the other women in Matsu no longer want to be traditional wives. In other words, contemporary Matsu households can no longer successfully operate on the assumption of the self-sacrifice of one of the partners (most often women). Quite the opposite, creating a common vision that both partners, along with the entire family, can work toward together has become the foundation of contemporary marriages and families in Matsu.

Conclusion: Struggling Women, Families, and the Future of the Islands

The cases of Cao Xiaofen, Li Xiufang, and Chen Lihong clearly show that the women of Matsu did not have much chance to receive higher education during the military period. Most women ended their education after elementary or middle school, and immediately began engaging in small-scale commercial business to help support their families or to provide their siblings with more opportunities than they had been given themselves. After marriage, they were expected to take care of their husbands and their families, and also to raise children. Although, as Chapter 3 indicated, they did obtain a kind of free space and greater power than they had in the earlier fishing period, most of them still struggled to be loyal sisters and filial daughters-in-law (e.g. Lee Reference Lee2004). Cao Xiaofen and Chen Lihong are clear examples: they both enjoyed school but were unable to continue their education because of family responsibilities. Despite her pregnancy, Cao Xiaofen had to obey her mother-in-law’s dictates and move to Taiwan to work in a clothing factory, living separate from her husband. The family took precedence over the individual.

Nevertheless, the examples of Xiaofen, Xiufang, and Lihong also show how a new female self-consciousness, one that was distinct from the sociocultural self, developed between the military period and the contemporary era. For instance, Xiaofen is the eldest of the three and the most constrained by traditional culture, encountering shattering separation, deaths and illness throughout her life; however, these sufferings have prompted her to reflect on the ultimate causes. With the support and care of her siblings and friends in Matsu, she was able to regain a new life. She became a new subject, not only managing her successful flower business but also putting great effort into sustaining emotional ties between her siblings. She works hard to reach a balance between her business self and the sociocultural one (playing the kinship roles of mother and eldest sister).

Xiufang also had the opportunity to go to Taiwan when she was young. She was fortunate in that she received higher education there and so was able to get a stable job in the Matsu government when she returned. Becoming a successful accountant is clearly a point of great pride for her. She is also proud of the fact that she is able to provide a comfortable home environment for her children. Nonetheless, she is upset that she cannot play the role of a “proper” mother—who cooks and cares for the family, holding it all together. Whether in life or in work, she is torn between two extremes—between 0 and 9, the traditional and the contemporary.

Lihong is very different, and from her situation we can see an intermediate stage between the traditional and the contemporary. Compared to Mahmood’s (2005) depiction of the ethical formation of Egyptian women, Lihong’s example presents an even better case of the burgeoning of a modern subjectivity. Lihong made the kinds of sacrifices that women in the traditional culture have long made, and she even took the decision not to study further so as to afford her younger siblings the opportunity to finish school. In the process, however, she began to develop her subjective consciousness, and formed plans for her own future and imagined what her life could be like. As a result, when her marriage began to flounder, she rejected a role of further self-sacrifice and refused to continue as the traditional wife. As she encountered myriad difficulties in the divorce process, her subjective consciousness became all the more engaged, and she pursued economic independence so as to gain custody of her son. Of course, after the dismantling of military rule Matsu society developed in myriad ways, and the new job options in Matsu have given Lihong more varied opportunities to develop her subjectivity. She can now make investments in her future, and actively seek out new employment so as to better herself and her situation.

Lihong’s case underlines the fact that marriage and family in Matsu today differ significantly from the past. That is to say, in contemporary Matsu, women’s self-awareness has come to the fore, and the continuation of a marriage and family depends on whether husband and wife are willing to negotiate and create a common vision for the family. In fact, this is true not only of marriages. In the Chapter 8, we will see that Matsu as a whole—from villages to islands—faces a similar challenge: how to find a common sense of the future in the midst of these multitudinous new selves.

When martial law was lifted in 1992, Matsu entered a new era brimming with freedom, openness, and hope. A civilian county government and county council were elected in 1994, and in that same year the first airport for civilians, albeit a small one, was completed, allowing people to visit Matsu freely. In 1997, a new ferry, “Tai-Ma lun” (Taiwan-Matsu ferry), replacing the old military personnel transport ships, began to sail between Matsu and Taiwan. The Taiwan government also initiated a route, called “three small links” (xiao santong), connecting Taiwan to Fuzhou, China via Matsu in 2001.1 With the widespread availability of the internet since 2000, Matsu became open to the entire world.

However, these forward-looking prospects did not obviate the many challenges Matsu still faced. The fishing economy was in the doldrums and many people had emigrated from the islands. Having lost its strategic significance in cross-Strait relations, Matsu was no longer as important to the state as it had once been. In 1997, the Taiwan central government launched a program of troop reduction, severely threatening Matsu’s economy which was heavily reliant on military supply. The situation worsened after Taiwan and China finally reached an agreement on mutual communication and implemented the “three great links” (da santong) in 2008. As a result of that policy, flights, voyages, and postal services could bypass Matsu (and another demilitarized island, Jinmen), and flow directly between China and Taiwan. In short, at the very moment that it gained its freedom, Matsu lost its significant role in cross-Strait relations. A strong sense of instability and uncertainty pervaded the islanders’ minds.

In the face of these enormous changes, many Matsu people, in particular those who went to work in Taiwan or made their way there via the guaranteed admission program during the WZA era and later returned to take important government positions, began to offer their own visions of the future by proposing new blueprints for Matsu. Over the next three chapters, I explore the processes by which these new visions, or new social imaginaries, have struggled to take form up to the present day. Unlike the top-down analyses of Anderson (Reference Anderson1991 [1983]), Appadurai (Reference Appadurai1996), and Taylor (Reference Taylor2004), I will begin with the imagining subjects themselves in order to investigate how a social imaginary takes shape. As Chapters 5 and 6 describe, the dismantlement of the WZA and the advent of online technologies had already liberated individuals to a great extent. Once individual imaginations have been engaged and developed, the question a society faces is how a collective consensus can be reached. Thus, in order to understand this era, it is crucial to examine the individual imagination and the process by which it is potentially transformed into a larger social imaginary. This is important for understanding not only Matsu but contemporary society in general.

Chapters 8 to 10 look at the capabilities of specific individuals and the tribulations they faced during the WZA era, synthesizing their life experiences to show how their daring and risk-taking spirits were fomented, and how individual imaginations are formed. I then discuss the different mediating forms through which they transform their individual imaginations into social imaginaries. In other words, I take these mediating forms as “technologies of imagination,” exploring how they create new social relationships and cultural capacities. These forms could be material, such as community projects and the building of a temple, as will be discussed in this chapter, or conceptual, such as new pilgrimages and a proposed fantastical gaming industry on Matsu, as explored in Chapters 9 and 10. My analysis in these chapters draws on Foucault’s thoughts on “ethical subject” (Reference Foucault1985, Reference Foucault1998) and Moore’s writings on “ethical imagination” (Reference Moore2011); however, the imagining subjects I define are not just individuals, but also cohorts of different generations, genders, and social categories. Having undergone similar life experiences and hardships, they are more likely to share common imaginaries. In these chapters, I give special consideration to these cohorts and scrutinize the new ways they evolve to reach out to others.

Community Building Projects in Taiwan and Matsu

In many ways, Matsu is similar to Taiwan, in that it has been under authoritarian rule and is wedged uneasily between two big political forces (China and Taiwan for Matsu, and China and the USA in the case of Taiwan). Both faced many similar and pressing problems such as how to reintegrate and redefine themselves after the authoritarian regime had gone. On reflection, it is not surprising that the Taiwan government started a “Community Building Project” (shequ yingzao jihua) in 1994, attempting to create a new sense of community which was previously suppressed by the authoritarian government. The project was launched by the Council for Cultural Affairs (CCA). The main project coordinator at the time was the vice-chairman of the CCA, a cultural anthropologist, Chen Chi-Nan. He observed that after Taiwan had freed itself from the rule of the Nationalist Party in 1987 and experienced economic growth, what was needed most was the rebuilding of communities (Reference Chen1996a: 109). He claimed that Taiwanese society had always embraced a strong sense of “familism” (Reference Chen1992: 7), “traditional localism,” and “feudal ethnic consciousness” (Reference Chen and bowuguan1996b: 26). Religion in Taiwan only functioned in the “private” and “mental” domains and was never directly involved in the public sphere (Reference Chen1990: 78). Therefore, it was necessary to build a new sense of community through community development projects. Only by doing so could Taiwan truly turn toward modernization and democratization (Chen Reference Chen and bowuguan1996b: 26; Chen and Chen Reference Chen and Chen1998: 31).

What actual steps needed to be taken to achieve this? Since the purpose was to create a new community consciousness, values, and identity, Chen suggested that culture was the most fitting starting point. By organizing various cultural activities and encouraging community members to participate, a sense of group identity could be fostered (Reference Chen1996a: 111). The activities promoted by the CCA were mostly related to art and culture, such as rebuilding the village landscape, organizing arts activities and architectural restoration, and researching local history and literature (Chen and Chen Reference Chen and Chen1998: 22).2

It is important to note that Chen Chi-Nan’s intriguing ideas and proposed project were not a rehabilitation of old values or culture, but rather a new national imaginary in the global terrain (Lu Reference Lu2002: 10) and a response to the global economy and the multiculturalism of Taiwan (Hsia Reference Hsia1999). They thus received strong support from the president at the time, Lee Teng-hui (Reference Lee1995), who was steeped in Taiwanese consciousness and incorporated Chen’s ideas into many of his speeches. These ideas were disseminated through different government institutions, and various subsidies and promotional activities quickly reached towns and villages everywhere in Taiwan. The surge of interest in community landscape building drew an avid response from professionals in architectural and civil planning fields (Hsia Reference Hsia1995, Reference Hsia1999). The idea of community development soon became closely linked to village preservation and had a huge impact on Taiwan.3

These ideas were brought from Taiwan to Matsu mainly by Cao Yixiong when he became a county councilor. Cao had not tested well enough to enter college after high school, so in the early 1970s he went to Taiwan at the age of eighteen to look for work. Drifting from a shoe factory to an electronics factory to a ceramics factory, he moved around quite a bit and was unable to settle into any vocation. He said that if given half a chance, he would just sit and read. It was a way for him to escape his feelings of discouragement and inferiority from not having gone to college. At that time, he encountered famous books of world literature rarely seen in Matsu, which were first translated and introduced to Taiwan under martial law by the Zhiwen Press’s “New Wave Series.”4 He was impressed by Hermann Hesse’s works: Beneath the Wheel (Unterm Rad), which severely criticizes education that focuses only on students’ academic performance, seemed particularly appropriate to his own situation. Reading Siddhartha and Der Steppenwolf also offered him a way out of his own struggles with his soul. As he put it, “These novels set my own imagination free…I felt that my life had meaning and a sense of dignity.” He also read a number of popular Western novels such as Gone with the Wind, One Hundred Years of Solitude, and The Thorn Birds. Remembering those years in Taiwan, he recalled, “That was my life: it was in the process of brewing.” He found great stimulation in these humanistic books, and the ideas he encountered penetrated deep into his consciousness.

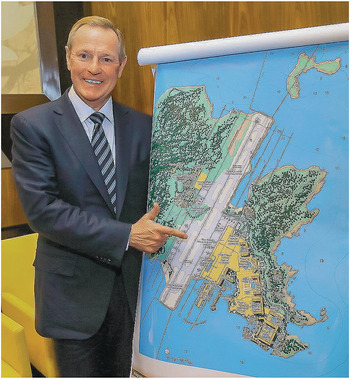

In 1982, Cao Yixiong’s former classmate, Cao Eryuan, who worked for an agricultural improvement station, helped get him a job in the engineer corps of the Matsu Bureau of Public Works, and he returned to his hometown to work as a bulldozer operator at the agricultural improvement station. Later, Cao Eryuan joined the Matsu democracy movement, and Cao Yixiong also became active in politics, participating in the “823 Jinmen-Matsu March” and the “507 Anti-Martial Law” protest led by Liu Jiaguo (see Chapter 5), and was eventually elected a county councilor. When Liu Jiaguo then decided to leave politics and to throw his efforts into the media realm, it came as a major blow to Cao Yixiong, who began to ponder what his own path should be. At that time, the WZA had just been dismantled, and he had to consider how Matsu could position itself anew. He chanced upon a series of books titled Changzhu Taiwan (Taiwan for the Long Term) at a bookstore in Taipei, written by Hsia Chu-Joe and some civil planning scholars (Wu Reference Wu1995). Cao was deeply inspired by the ideas about the value of local traditions presented in the series, and subsequently invited Professor Hsia to Matsu to give talks on “Local Development and Community Building.” Hsia introduced the ideas of the civil planning scholars and those of Chen Chi-Nan to people in Matsu. Later Cao had the opportunity to visit Tsuma go yuku in Nagano, Japan, a place known for its successful preservation of historical streets and buildings. After the visit, he began to promote the community building project Changzhu Matsu (Matsu for the Long Term) in his hometown, Ox Horn.

This chapter uses examples of community projects carried out in Ox Horn to explore the question of whether religious practices are necessarily an obstacle to modern thoughts as claimed or implied by policy makers and intellectuals. In the Matsu Islands, we will see that earlier efforts at community building—which included literary and historical research, art and cultural events, and activities connected to village preservation—yielded little success in terms of creating a sense of community identity and consciousness. It was not until the community building activists became aware of the importance of religion and began to negotiate with villagers and to participate in building the temple that a sense of community began to emerge. In this case, religion and in particular the process of its materialization through temple building serve as a basis for the formation of a new community. They also function as important mediums for absorbing modern concepts of cultural preservation, environmental aesthetics, and imagining tourism development.

Village of Nostalgia

As I stated in the introduction, Ox Horn had once been the biggest fishing village on the island of Nangan. Because of the decline of the fishing economy, the population was greatly diminished during the military period. From 1970 to 1990, the population decreased from 1,300 to 750. Abandoned and dilapidated buildings were everywhere. With village preservation as its core objective, “Changzhu Matsu” began by reorganizing and restoring the eastern Fujian-style stone houses in Ox Horn. Responding to the county councilor’s appeal, a group of Matsu educated elites participated in the project; they came not only from Ox Horn, but included teachers, cultural workers, and artists from different villages, and even many young architects who were doing their military service in Matsu. The group held a variety of cultural and artistic events, and invited renowned music, art, and dance groups to perform. In 1999, a “Civil Planning Workshop” (chengxiang gongzuofang) supported by the government was set up in Ox Horn to design a number of village preservation plans. The figure below shows the prospective appearance of Ox Horn, according to the plans of these community development activists (Fig. 8.1).

The figure demonstrates the initial concepts of the community development activists. They invented new names for places to convey a strong nostalgic flavor or to make reference to local history, such as the Fishing Hut Café, Ox Horn Teahouse, and Local Classroom. Although the actual implementation process did not always follow the original plan set out in this figure, it did not stray too far from it. After the successful execution of the project, Ox Horn attracted much attention in the media, thanks in part to its county councilor’s networking ability. The results of the development project also garnered numerous national awards.

Nevertheless, the media reports and national awards were recognitions gained outside the village. For the development of a community, it is essential that community activities elicit the participation and interest of local residents. And the fact was that local villagers, especially the elderly residents (who were still highly influential in village affairs), played a very passive role in most of the activities.5 Perhaps it was their fishermen background that made them feel awkward about being involved in these elite-led cultural projects; in any case, they were uninterested in taking part. In fact, they frankly told me that restoring the old houses was simply “doing dead things” (F. tso silai), something that was for them utterly pointless and meaningless. Therefore, the old houses were still demolished one after another and rebuilt in cement. The vast horizon of Ox Horn became gradually blocked by tall, modern buildings.

The community development leaders, however, still moved ahead. Under the influence of new community concepts such as “sustainable management” and “cultural industrialization,” they raised funds to open businesses in these restored historical buildings. It may come as no surprise that these stores ended up vying fiercely with one another for business owing to stiff market competition (see also Y. Huang Reference Huang, Huang and Chen2006a). The community development implementation process created new groups working in parallel to the village’s administrative system, as also happened in other places in Taiwan (Chuang Reference Chuang2005), resulting in friction and conflicts. In the end, many activists withdrew from the project and some formed other associations.

At about the same time that this community development was being carried out, a temple committee was formed by the local people on their own initiative, with the goal of building a temple in Ox Horn. The role of religion in Matsu therefore deserves consideration.

Religion in Matsu

The deities in Matsu have strong eastern Fujian characteristics that are distinct from the southern Fujian belief system in Taiwan (H. Wang Reference Wang2000). Ox Horn presents a useful example of this difference. The deities of Ox Horn worship can be divided into four main categories. The first consists of deities of a higher status who were brought over from mainland China, such as Wuling Gong or Wuxian Gong, whose origins can be traced to the Five Emperors from Fuzhou (Szonyi Reference Szonyi1997: 114). Second are the deities who possess special powers, such as the Lady of Linshui (Linshui Furen or Chen Jinggu) who is venerated for her powers relating to childbirth (Baptandier Reference Baptandier2008). In Ox Horn, villagers set up a shrine for her after some local women experienced difficult labor. The third category comprises gods who came to be deified because their corpses or statues floated to the shores of the village and over time the villagers associated certain miraculous events with them. After having found the bodies or statues, the villagers buried them or built simple huts to shelter them from the rain, and as some wishes were answered, particularly for big harvests of fish, they started to be revered and worshipped. General Chen (Chen Jiangjun) and Madam Chen (Chen Furen) are two such examples. The last category is that of the territorial deities who ensure the wellbeing of the place, such as the Lord of the White Horse (Baima Zunwang) and the Earth God.

As mentioned, many of these deities mentioned above have strong eastern Fujian origins, such as Wuling Gong, the Lady of Linshui, and the Lord of the White Horse, but religion in Ox Horn is also inseparable from a particular physical characteristic of the islands: the sea, which continually brings things to their shores. The religion of Ox Horn, or of the Matsu Islands in general, is therefore a unique combination of eastern Fujian culture and elements of the oceanfront geography inherent to Matsu.

The deities are indispensable to the villagers’ lives, as they journey through life’s stages, experiencing birth, old age, illness and death. The Lady of Linshui is a goddess in charge of pregnancy and taking care of children. Before weddings, an elaborate day-long rite (F. tso tshuh’ iu) is carried out to show gratitude to her. When villagers encounter illness or misfortune, they seek help from Wuling Gong, Wuxian Gong, or General Chen. They are also the deities who protect fishermen at sea. The Lord of the White Horse, as a territorial deity, is in charge of death: when anyone dies, his or her family has to “report the death” (F. po uong) to him.

The Ox Horn villagers initially did not build a temple for their deities, but only set up incense burners for them and kept the burners at villagers’ houses, either because of their poverty or because they saw the Matsu Islands as just a temporary home. Nevertheless, if the house in which a deity’s incense burner was kept became dilapidated, the villagers would raise funds to renovate or rebuild it. Sometimes, if a family built a bigger house, the incense burner would be moved there so that the deity could have a better dwelling place. If a deity had exerted special powers to help a family, such as curing their son of a serious illness, the family would set up an incense burner in their house dedicated to the deity to invite the god to stay with them permanently. Becoming “the adopted son of a deity” (F. ngie kiang) is a very common custom in the Matsu Islands. Thus, villagers’ lives are intimately connected with their deities.

The relationship between the villagers and their deities was not limited to the domestic domain, however. Since Matsu residents came over in waves from mainland China, their homeland kinship ties influenced their choices of residential location. The first arrivals congregated in areas populated by families from the same region in China. Over time, each area was then further subdivided according to the particular deities worshipped by its families; the settlement gradually became fragmented into several distinct neighborhoods.

Bordered by a bridge, Ox Horn is divided into “Ox Horn Bay” towards the north and the “Line of Six Houses” towards the southwest of the village (Fig. 8.2). Ox Horn Bay is mainly populated by families with the surname Cao, though families with other surnames are also interspersed throughout this region. In the past, the majority of the population made their living by fishing or running small businesses. The Line of Six Houses, on the other hand, was inhabited by a mixture of different surnames who moved into the neighborhood from various places in China. As revealed by the name of the neighborhood, the earliest settlers lived in a row of six houses and had the surnames of Li, You, Cao, and Zheng—thus, it was a rather heterogeneous composition. Surrounding the Line of Six Houses is a large stretch of farmland. The early residents made their living by farming and fishing.

The residents of Ox Horn Bay and Line of Six Houses further differentiated themselves by venerating different deities. The former worshiped Wuling Gong, who was brought from China by a Cao family, General Chen, the Lady of Linshui, and the local deities the Lord of the White Horse and the Earth God. As I described earlier, most of these deities originally resided in the residents’ houses but were then moved to a temple in Ox Horn Bay after it was built in the 1970s. The latter, the Line of Six Houses, also have their own deities, such as Wuxian Gong, brought by a Yu family, and Gaowu Ye (a minor deity). Although the inhabitants of the Line of Six Houses also worship Wuling Gong and the Lord of the White Horse, these deities had their own incense burners and statues and did not mix with their counterparts in Ox Horn Bay. Every year during the Lantern Festival (F. pe mang), the two neighborhoods held their own nighttime rituals, but on different dates. Each neighborhood had its own percussion band, and if the bands crossed paths, they usually ended up in heated competition with each other.

Looking more closely, Ox Horn Bay is further divided into different territorial units: for example, the Ox Horn Slope along the mountains, Southerners’ Place (populated by residents from southern Fujian), Big Bay (which includes the old market street), and Western Hill. Each unit has its own deities and festivals. Every year during the period between Chinese New Year and the Lantern Festival, the whole village has to celebrate the same festival as many as eleven times! This high frequency of nighttime rituals became increasingly difficult for most people in Ox Horn, especially as many Matsu people had shifted from being dependent on a fishing economy that dictated the pace of life according to the tides and the fish, to having a lifestyle determined by the new county government that was set up after the military government was abolished in 1992. The new nine-to-five work routine created a need to integrate the various rituals. The construction of a new temple presented a possible solution to this problem.

Giving Way to Religion

Aided by the county government, the Ox Horn Community Development Association (shequ fazhan xiehui) was established in 2001, and a second phase of community development started. Since most of the non-local members of the first phase had left the group, the association was largely composed of village inhabitants. They elected Yang Suisheng as the chair; the county councilor, Cao Yixiong, was also invited to join the association.

Yang is a typical Matsu educated elite who was sent to Taiwan by the government guaranteed admission program to study medicine thanks to his outstanding scores in high school, and who then came home to serve his community in 1981. As a doctor, he received modern medical training and was inculcated with a love of scientific ideas and values; he was the first person in Ox Horn to build a Western-style house, which he designed himself. At the same time, his attachment to his hometown is also strongly emotional. Motivated by the idea of preserving and reforming his hometown, he decided to lead the association. Most of the members in the association were similar to him: most were middle-aged and had gone to Taiwan or Europe to attend university and returned home to work, but there were also some members who were of the older generation.

Given the intellectual background of its members, the association began, unsurprisingly, by holding art and cultural events resembling those in the first phase. But Yang also designed many other activities for older people. For example, he invited migrant elders back home to tell stories of the past, and, understanding that they were mostly fishermen, he executed an environmentally conscious project to prevent sea waste from flowing into the bay. Although a greater variety of events were organized than in the past, the association soon faced the same problems that had plagued community development activists of the previous phase: their plan did not capture the interest of locals, and participation was low.

Though frustrated, Yang noticed that older members (along with other villagers in general) showed a strong enthusiasm for temple building. Whenever the subject was brought up, they discussed the issue fervently. He gradually realized that the association’s ideas of community could be accepted and implemented effectively only if they changed their view of religion as mere superstition, participated in temple building, and engaged with the residents about their conceptions of Ox Horn. He thus reinterpreted local religion as “folklore” (minsu) without much religious implication, a view that was embraced by the intellectual activists on the committee, who began to actively engage with building the temple. After that, the Community Development Association worked closely with the temple committee and often held joint meetings. In order to formalize their coming together, a member of the association proposed integrating the temple committee into the association. Although this proposal did not receive support from the older population, it helped the middle-aged members to realize that they had to change their ways of thinking in order to succeed in implementing their ideas of community development. Yang said:

Originally, we thought of the community as a big circle, and the temple committee as a smaller circle within. But then we had to change our way of thinking… we had to hide ourselves [the association] within the temple committee and use their power to strengthen our own.

This statement shows that the community activists came to understand, after reflection, the importance of religion in local society and were willing to change themselves, and even to “merge the association with the temple committee.” A shared imaginary of the village was finally taking shape.

Materializing Community through Temple Building

Aside from the religious reasons and the need to adapt to modern life rhythms, the enthusiasm for building a temple also stems from the highly competitive electoral politics in Matsu after its democratization. Elections depend on votes, and thus on the support of local communities. While other villages had successfully integrated different neighborhoods through joint construction of their temples, Ox Horn faced more thorny issues and remained fragmented, much as it was during the fishing period. Since Ox Horn had once been a major village, its residents were very anxious to build their own temple. It is for this reason that the villagers initially only elected proprietors of construction businesses as the directors of the temple committee. However, as Ox Horn is located between two mountains, with many houses built along the slopes, it was very difficult to find an ideal site for the new temple; even though discussions had been going on for almost a decade, the five previous directors had not been able to decide upon a suitable location. Faced with increasingly heated elections, and with the temple still unbuilt, the committee decided to organize a ritual to bring the whole community together. As I indicated above, different neighborhoods originally celebrated the most important ritual—the Lantern Festival—on different days. After negotiation, one day was chosen for all the households to get together on the same night. This unification was initially successful, and Ox Horn-born Cao Erzhong, who spearheaded the effort, was voted into the national legislature. Unfortunately, the success was largely superficial: he later lost his bid for re-election (as we know, one quick ritual may temporarily assuage an urgent predicament, but it cannot resolve the underlying issue), and only then did the plan for construction of a temple return to the fore. However, the process of temple construction was tortuous.

The Temple Location and Sanctuary

After failing to win re-election in 2001, Legislator Cao Erzhong decided to restart his political career by devoting himself to temple building. The first problem he encountered was finding an ideal location for the new temple, which was a challenging task because of the mountainous geography of Ox Horn. In the beginning, a suggestion was made to build the temple around Ox Horn Bay by filling up part of the sea with earth from the mountain, but the committee members held differing opinions on the matter and an agreement could not be reached. Later, someone suggested the old location of the County Hospital, but there were problems with the property rights and the idea had to be abandoned. Then the thought of using the site of a liquor warehouse was brought up, but the villagers were opposed to this location because it had been used earlier as an execution site and a military brothel by the army. The committee members looked everywhere for a suitable location, and after numerous thwarted efforts, the focus returned to Ox Horn Bay. After much discussion and re-examination of the location, the villagers managed to come to a final decision. This brought joy and excitement to the village, and Legislator Cao was widely recognized for his dedication to the matter. In the next election in 2004, he was able to garner 69.8 percent of the votes from Ox Horn, an increase from 61.5 percent in 2001. His opponent’s votes decreased to 26.9 percent from 38.5 percent. In Ox Horn alone, Legislator Cao won by nearly 300 votes over his opponent and was easily elected.

Besides politics, the new temple also effected a successful integration of the various deities from the two neighborhoods of Ox Horn: Ox Horn Bay and the Line of Six Houses. As described above, the two neighborhoods are peopled by residents of diverse surnames and deities, and the building of a new temple presented an opportunity for people from the two long-separated neighborhoods to sit down and discuss how to combine their respective deities and festivals. When they came to an agreement on the hierarchy of the deities and arranged them accordingly into the seven sanctuaries in the temple (Fig. 8.3), the people of these separate neighborhoods were also unified. As one important temple committee member put it: “Once the temple is built, it will unify not only the deities, but the people as well.” Since that time, the villagers have worshipped each other’s deities, and also combined the eleven separate times of worship into two.6 Other rituals, hitherto practiced separately by the people of Ox Horn Bay and the Line of Six Houses, have since been united.

The Architectural Form

The process of deciding on the architectural form of the temple demonstrates the politics of negotiation between elder villagers and middle-aged community activists. The older members of the temple building committee favored a palace-style temple of the kind recently completed in a neighboring village. They were impressed by its ornate and opulent appearance, displaying the substantial wealth of the village (left panel of Fig 8.4). The middle-aged community activists, however, preferred the common island-wide architecture style, called “fire-barrier gables” (fenghuo shanqiang) (right panel of Fig. 8.4).7 They believed it would better represent the eastern Fujian heritage of Matsu culture, and they made great efforts to convince the village elders of this idea.

Fig. 8.4 Temple in palace-style (left) and Eastern Fujian-style with “Fire-barrier Gable” (right)

Perhaps the idea of valuing distinct local characteristics as advocated in the first phase of the community project had influenced the older committee members over time, since it did not take long for them to accept the suggestion. A draft of the new temple was quickly drawn up by the same architect who had participated in the first phase of community development. Using the structure of the old temple as a basis, he expanded and modified it, and also added new elements. This version was later made more attractive by painting it colorfully, and it was unveiled at the banquet of the Lantern Festival celebration (Fig. 8.5). The temple committee successfully raised almost NT$10 million on that single night!

Fig. 8.5 Coloring the draft of the temple

The next debate was over the material for the temple walls. The members of the older generation leaned towards green stone, which is not only resilient to climatic changes, but also serves as a symbol of wealth and high social status. In the early days, when the people of Matsu acquired wealth through their businesses, they would go to China to buy high-quality green stone to build new houses, and for this reason village elders naturally preferred green stone for the walls of the temple. But the middle-aged activists had been nurtured by concepts of community building, which approaches architecture from environmental and aesthetic perspectives. They favored granite because its color complemented the traditional stone houses of Matsu and the surrounding greenery of the mountains. They thought the temple would look too subdued and dull if the walls were green. The two sides held strongly to their own opinions and consensus proved elusive for quite some time. In one of the rounds of negotiation, a middle-aged member used sharp rhetoric to express his stance, which seriously offended the elders and caused them to withdraw from the meeting. Although middle-aged members softened their attitude, efforts to establish communication between the two sides proved to be in vain. In the end the issue had to be resolved through an open but very tense vote by show of hands, in which granite won over green stone by a single vote.

Next in question was the color of the fire-barrier gable. This time it was the middle-aged activists themselves who held diverse opinions. Legislator Cao preferred red, which is traditionally seen as a festive and auspicious color, but a local artist who had studied in Spain proposed black. By doing so, he hoped to present a unique color aesthetic through the stark contrast between the red outer walls and the black gable. But painting the gable black was seen as too subversive and was not easily accepted by other members. In the end, the members suggested the idea of dropping divination blocks to ask the deity for guidance on the final decision. Knowing that he would not be able to win the older members over, the artist did not show up for the divination, and the proposal for red was accepted.

As for the interior of the temple, the middle-aged members had always thought the village lacked a large public space that could be used for gatherings by the entire village, so their design of the temple offered a substantial common area suitable for community activities and events. For instance, their plans included a courtyard for small-scale public events. This concept had not previously been applied to any temple in Matsu. The temple as a whole was designed as a two-story building in which the ground floor could be used to hold an important banquet for all the villagers after the Lantern Festival. Further, the middle-aged members of the temple board extended the staircase leading towards the entrance of the temple for future use when a stage will be constructed to present Fuzhou operas and other entertainment programs.

The Trails, the Little Bay, and the Old Temple

The trails next to the temple used to be part of the lives of the people in Ox Horn, but the area was closed off and became a “forbidden zone” during the military period. After the abolition of the military administration, the community development association applied for government funds to clean up and restore the trails. The new trails do not necessarily preserve the old look, but instead expand towards the coast, and are designed to connect with the new temple, as part of the greater aim of linking the important tourist sites in the village (Fig. 8.6).

Fig. 8.6 The old and new Ox Horn temples

The little bay behind the temple holds a similar meaning for the villagers. Although filling it with earth would have created a larger area for the temple, the little bay is also a cherished and protected memory from the childhoods of most of the villagers who recount vividly how they played in the water or were chased by the coast guard soldiers. Therefore, rather than filling in the bay to create more land, the temple committee decided to preserve the villagers’ precious memories.

The most spectacular aspect of the temple area, however, is the manner in which the new and old temples exist side by side, aligned back to front. All the other villages demolished the old temples when building new ones. The construction team of Ox Horn temple initially also sought to do the same, and the elder villagers did not show any strong opposition to the idea. But the middle-aged activists, keen on preservation, were reluctant to do this, as they considered the old temple to be a part of their history. When the committee visited the root temple in China, they asked for the deities’ opinion by dropping divination blocks. The deities indicated that the old temple should not be demolished, as it was there that the Ox Horn deities had attained their power (dedao). As mentioned above, the new temple was designed according to the old temple’s form, with the addition of new elements. Now the new and old temples are juxtaposed: the old one is small but exquisite and the new one modern but culturally sensitive. They look similar in form but differ in detail, complementing each other and bringing out a unique aspect of Ox Horn.

Surrounding Landscape

The design of the new building also takes into consideration the issue of how to connect the temple with tourism. In the overall design, the middle-aged activists further contributed the idea of building a mezzanine between the first and second floors: a space in the shape of a half-moon. Its location is such that it allows people to see the contours of the northern island, as well as the beautiful scenery formed by the tiers of houses overlapping the slopes of Ox Horn. The design of the mezzanine was initially part of an effort to link the temple to future potential tourism, but interestingly, this space gradually developed a kind of religious meaning. In other villages, people say that it is the deities of Ox Horn who requested that the mezzanine be built so that the temple, situated between the mountain and the sea, would have a more solid foundation and in order that the “gods can sit firmly” (shenming caineng zuode wen). This example shows how the concepts of the community activists were translated into ideas with religious significance and subsequently became widely accepted by the Matsu people.

In order to attract more tourists to the village, the committee members also designed two separate entrance and exit paths. The committee applied for funds from the Matsu National Scenic Administration to build a pavilion (which was later changed to an observatory) above the temple that would allow tourists to admire the surrounding scenery from different angles. The eaves of the temple are engraved with a “legendary bird” that was recently found to be close to extinction—the Chinese crested tern (or Thalasseus bernsteini)—which all the more highlights the local characteristics of the Ox Horn temple.

Temple, Community, and the Matsu Islands

The description of the temple reveals how the temple building not only provides a space for the two distinct neighborhoods to develop a unified sense of community, but also a way for the local people to adapt to the pace, especially the nine-to-five workday routine, of modern society. It successfully merged the deities from different neighborhoods into one temple and reduced the frequency of rituals to help the people cope with the rhythm of work in modern society. Residents from different generations negotiated with each other throughout the construction process: the activists infused the new temple with their own ideas about architectural aesthetics, local characteristics, and concepts of organic living. Older members offered their knowledge of traditional beliefs, and local residents provided the necessary funding and labor. Together, they built the temple for both the past and the future.

This process has been enthusiastically recorded online. A person with the username “Intern” (Shixisheng) posted one picture each day on Matsu Online, throughout the two-year long period of construction. “Intern” finally made a GIF animation, dedicating it to:

all the villagers who contributed to the construction of the Ox Horn temple and the villagers who moved out. Many thanks to the craftsmen from mainland China and to all the community members who worked together to support this project!

Many new community activities were organized after the temple was completed. After its inauguration on January 1, 2008, the temple launched an unprecedented pilgrimage to China in July, in which more than 300 villagers participated (to be discussed in Chapter 9). When a disastrous fire destroyed the business area in Shanlong as I noted in Chapter 5, Ox Horn temple held a fire-repelling ritual for all inhabitants to ward off the fire spirit.

The momentum of the new Ox Horn was also demonstrated in the elections for county commissioner in 2009 and legislator of Matsu in 2004. The director and other leaders of the temple construction project obtained an unprecedented number of votes; two of them were duly elected to these two positions. Nowadays, the temple in Ox Horn plays an even more significant role in integrating traditional culture and modern society in Matsu. Since 2011, for example, the temple committee has cooperated with the Matsu Cultural Affairs Bureau to hold an annual coming-of-age activity. It combines the traditional Matsu ritual of xienai, in which teenagers turning sixteen offer thanks to the goddess Lady Linshui, with the values of a modern high school education.8 This ritual gives high school students in Matsu a chance to celebrate their coming of age while sustaining their traditional customs.

The close connection between temple leaders and elections, however, has cast a shadow of factionalism. Criticisms have appeared on Matsu Online, with claims like “the temple has turned into an election tool” (Shenhua Reference Shenhua2010). Others have said that the temple committee elections are “preliminary battles for legislator seats” and that “the village leader’s faction is being oppressed by the temple board.” Voices of dissatisfaction can also be heard in private settings. Indeed, the discord between the village leader and the community building committee that had developed in the previous phase of the community project persisted throughout the process of temple construction. It would obviously be a gross exaggeration to claim that the building of the new temple could resolve all of the longstanding disagreements about elections and disputes between political factions and disgruntled individuals. Nonetheless, we should not overlook the importance of the temple building in breaking many of the deadlocks that had formed during the community building project, nor should we underestimate the hard work contributed by the majority of the inhabitants. This ethnography, in a very important way, provides us with a lens through which to examine how a divided community can reach a consensus in contemporary Chinese society. Yang Suisheng, former chair of the community development association, later the head of the temple building committee, and subsequently elected Matsu county commissioner, gave a vivid description of this process:

The temple of Ox Horn not only integrates traditional architecture, folk beliefs, and local culture together, but also provides a space for new community activities. There have been many ups and downs in the process of building the temple. Each step along the way has been full of compromises negotiated in locally democratized ways. The result is a collective achievement of grassroots democracy

Grassroots Democracy

It is worth examining the idea of “grassroots democracy” a bit more, particularly the process through which the middle-aged activists communicated and negotiated with their elders. As I mentioned earlier, during the negotiations the so-called “democratic” method of voting was often only used as a last resort, when a consensus could not be reached after substantial communication. Usually, the middle-aged members would talk to the older members in private, and if the two sides strongly insisted upon their own views, they would decide the matter through the use of divination blocks. What is worth noting is that this method does not always yield yes or no answers; the responses often fall into a grey area, necessitating further communication among the members.

The divination blocks consist of two crescent-shaped blocks with a flat side and a convex side. Dropping the two blocks can yield three different combinations: a positive answer (meaning the deity gives its consent: one block facing up, the other facing down, +-/-+), a negative answer (meaning the deity disagrees: the flat side of both blocks facing downwards, --) and an ambiguous answer (also called a “smile,” meaning the god smiles but refuses to answer: both blocks facing upwards, + +). In other words, by the laws of probability, there is a 25 percent chance that the deity will refuse to answer and will throw the question back to the worshippers. This allows them to modify their question before coming back to the deity for another answer, thus providing a chance for the various participants involved to renegotiate and reach a form of consensus. The worshippers can also set up certain rules depending on how significant the questions might be. If the issue is one of little controversy, then it needs only one positive answer from the god. If it is one of great importance or could lead to severe consequences, three (or more) positive answers in a row may be required to validate the result. By this method, the local people are given more opportunities to communicate. The whole process exemplifies another kind of democratic civility (Weller Reference Weller1999), in which final decisions on contentious or significant matters are reached not just through group discussion, but with the support of the deities.

Conclusion: Community, Mediation, Materialization

This chapter probes how old conflicted and fragmented social units in a settlement came to be integrated after the reign of the military ended and formed a new community. Since the beginning of the twentieth century, popular religion has been seen as an obstacle to the modernization of China, and thus suppressed by the state and discounted by intellectuals (Duara Reference Duara1991; Goossaert and Palmer Reference Goossaert and Palmer2011; Nedostup Reference Nedostup2009; C. K. Yang Reference Yang1961; M. Yang Reference Yang and Yang2008). This chapter shows that their counterparts in contemporary Taiwan, and even the educated people in Matsu, have similarly taken a dismissive view.

The role of religion was initially overlooked in cultural policymaking and in its local execution. The first phase of community building in Ox Horn focused on literary, historical, and cultural activities, like most community building efforts in Taiwan at the time. But such activities failed to elicit the participation of local villagers. It was not until the second phase of community building, when Yang Suisheng, the chair of the community development association, and the middle-aged activists understood the expectations of the local residents and the important role played by religion in their daily lives, that community building experienced a breakthrough. After their ideas changed, committee members began to participate actively in building the temple, which in their own words was an attempt to “build from the inside” (neizao) rather than “build from the outside” (waizao)—meaning to take part in the construction of a building that occupies a significant place in the heart of the villagers, instead of organizing activities that are only valued by the middle-aged generation. On one hand, they incorporated local religion into their ideas of historical preservation, environmental aesthetics, and tourism development. On the other hand, their concepts of community were translated into ideas with religious significance and subsequently became widely accepted by the Matsu people.

This chapter demonstrates how religion and, in particular, its process of materialization through temple building, could provide an important medium for creating a new community. Taking inspiration from important works in material culture (Miller Reference Miller1987, Reference Miller2005), we have seen how cultural concepts (of community) and social relations (of Ox Horn) have been reconstructed by the residents and by their deep engagement with the temple. The process of temple building, and how it materialized the negotiation of conflicting ideas, provides us an excellent example of contemporary community formation.

In fact, not only the temple, but also myths of deities and the practice of dropping divination blocks can create a civil space of negotiation and help to translate the ideals of community building into concepts that are accessible to the villagers. Different individuals or generations with varying values were able to find a way to resolve their disagreements, and the two neighborhoods that had long excluded each other were able to integrate into a unified community. The temple building process demonstrates how religion and religious artifacts can serve as the basis for the emergence of a new community and as a means of absorbing modern ideas. Without them, new and external concepts often only have a short-term influence and very rarely can take root in a local society.

I am not arguing, however, that the case of Ox Horn’s temple construction is merely a revitalization of traditional culture or values. Instead, I aim to show how religion, community, and space in the contemporary Matsu Islands have more complicated articulations than in the past. Religion, by subsuming diverse elements, has become more collage- or montage-like in contemporary society. It has transcended its previous form and challenges us to reconsider what it is today.

After the inauguration of the new temple on New Year’s Day of 2008, Ox Horn organized a five-day pilgrimage to China, from July 5–9. Because the completion of the new temple had realized a long-awaited dream of many Ox Horn villagers, this pilgrimage won strong support from local residents and village emigrants living in Taiwan. Including pilgrims from other islands, more than 300 people took part. In the procession, one could see the temple committee members holding statues of Wuling Gong and the Lady of Linshui, young people carrying sedan chairs and puppets, women playing drums and gongs, and pilgrims following behind.

That this pilgrimage was aimed at more than religious renewal is evident in its name: “Matsu-Ningde First Sail: Changle Pilgrimage.” That is, they did not directly head for their ancestral temple in Changle, but instead undertook an elaborately planned journey across the Taiwan Strait, starting from Taiwan and arriving in northeast Fujian Province (Map 1). The five-day itinerary was as follows:

6 July—Ningde → Pingnan (Baishuiyang Scenic Spot)

7 July—Pingnan → Gutian (Linshui Temple) → Fuzhou

8 July—Fuzhou → Changle (Longshan Temple) → Fuzhou

9 July—Fuzhou → Mawei → Matsu

The organizers rented the Hofu Ferry and departed from Keelung Port in Taiwan, where they invited officials from the Ministry of Transportation and the mayor of Keelung to a press conference. After stopping in Matsu to pick up local residents, the ferry proceeded northwest into Sandu’ao Port and reached Ningde City in Fujian, China, where the city government welcomed the pilgrims in celebratory style. The next day, the pilgrims boarded a bus and headed northwest to the Baishuiyang Scenic Spot, before traveling south to the Linshui Temple in Gutian County, the root temple of the Lady of Linshui. They then continued further southward to Fuzhou, where they finally arrived at the ancestral Wuling Temple in Changle.

We may wonder why a pilgrimage held by people from Matsu would choose Keelung as its starting point? Why was Ningde, a city not well known in Taiwan, chosen as the point of entry into China? Why did a pilgrimage to the ancestral temple have to take a detour towards the northeast and arrive at Changle only after visiting the Linshui Temple in Gutian?