Memories of a Murder

One evening around dusk, the company commander of military base 99, located just above Ox Horn, caught sight of Guoxing—a soldier from Jinmen who had been transferred to the Matsu Distillery in the village—heading toward the house of his lover Xuemei. The company commander immediately grabbed his bayonet and strode toward the village.

Xuemei was an attractive woman. She had been dating the company commander for a while when she also began to get close to Guoxing, who frequently went to her house to chat and flirt. The commander had seen him heading there many times and suspected that the two were having an illicit affair. It was around five o’clock that evening, and the commander had already planned what he would do. Watching Guoxing go into her house, he armed himself and hurried straight there.

He barged into the house and attacked Guoxing with his bayonet in a rage. Although badly wounded, Guoxing managed to escape in the confusion. The commander did not bother to follow him. Instead, he turned his attention to Xuemei, forcing her into a corner and stabbing her dozens of times until she collapsed dead in a pool of blood.

Having murdered Xuemei, the commander left the house to find Guoxing. He did not give chase, but rather stood near the doorway of Xuemei’s house and kept watch. He knew the layout of the village so well that there was nowhere Guoxing could escape him.

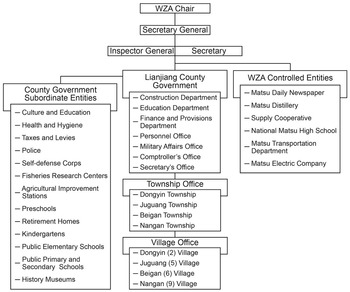

Bleeding and desperate, Guoxing fled down to the bay to try to find shelter with the soldiers at the Port Military Base, screaming, “Help me! Help me!” But the soldiers had no orders from above and did not know who he was, so they warned him away as he approached. When Guoxing saw that they had no intention of protecting him, he headed back across the village. He passed the central state school to the county hospital, looking for someone to help him. But since it was after five o’clock, the hospital was closed, and the military doctors and nurses had gone home.

Guoxing had no choice but to turn in another direction, likely heading toward the village administrative office. His shrill screams for help carried throughout the village, but no one dared to come out and aid him. The company commander heard him and headed toward his voice. A little past the rice storehouse, he caught up with Guoxing and repeatedly stabbed him in the back. Guoxing collapsed and died beside the fishing nets outside a villager’s house. Then the company commander calmly left the village and returned to the military barracks without so much as a backward glance.

The day after these events occurred, the commander was arrested at military base 99. Because the circumstances involved not only the taking of two lives, but also the highest-ranking official on the island ever to be implicated in a crime, the news had risen through the lines of command to the very top. The judgment came quickly, and announcements of the time and place of the execution were posted all over the island.

Early on the day of the execution, the commander’s hands were bound and a wooden tablet stating his crimes was fastened to his back. He was made to stand in the back of a military truck and was driven from village to village as a warning to the public. Finally, he was taken to the execution site near the entrance to Ox Horn. Many villagers, even those who were just primary school students at the time, witnessed the execution. “Although terrified, we were curious to see what would happen,” they said. Their descriptions of the execution are particularly striking:

Across from the execution site was a hill covered with military police. They all carried guns—it was scary!

The military commander was pulled off the truck and made to kneel at the foot of the hill.

They offered him some food. He didn’t eat anything, but he drank the sorghum liquor they gave him.

After that, the placard on his back was taken off and thrown to the ground. It was time for the execution.

Six executioners lined up in a row with their guns pointed at his head. In fact, only one of them was going to shoot, but they wanted a show of force.

Before he was killed, the company commander let out a shout, something like “Long live the Republic of China!” or some such patriotic motto.

Everyone fell so silent that it was as though we could hear each other’s hearts beating.

Bang! Bang! Bang! There were three shots in a row, but the commander didn’t fall. He wasn’t dead! According to the custom, if three shots didn’t kill the criminal, it meant he wasn’t destined to die. But because the circumstances involved someone so high up, the higher-ups at the WZA had already made their wishes known: “He must die!” So they shot him once again.

I heard his last sigh…oh!…and he was gone.

Cao Daming, an Ox Horn villager who at the time was barely fifteen years old, later helped the deputy head of the village investigate the case and so could describe the events vividly even forty years later. Others remembered the case clearly because they had witnessed the execution. This event gives us an important perspective on the reign of the military in Matsu. How was military rule imposed on the islands? How were the people governed? In a place which had never been directly governed by a state power before, how did the locals conceptualize the military state?

The Advent of the Military State

When Chiang Kai-shek’s army suffered successive losses against the CCP (Chinese Communist Party), his government withdrew to Taiwan in 1949, while the KMT (Kuomintang, Nationalist Party) armed forces retreated to the islands along the coast of southeastern China. In 1949, Chiang’s army reached Matsu, and in 1950 they set up the Matsu Administrative Office (Matsu xingzheng gongshu) with jurisdiction over the archipelago of Matsu and the islands to the north. After the northern islands fell into enemy hands in 1953, the KMT government set up three county administrative offices in Fujian—Lianjiang, Changle, and Luoyuan—on the islands of Nangan, Xiju, and Dongyin, to symbolize that Chiang Kai-shek still governed Fujian province, and therefore more generally the rest of China.

Simultaneously, the KMT established the East China Sea Fleet (Donghai budui), which included fishermen from coastal Fujian, pirates (such as the aforementioned Zhang Yizhou and the former “National Salvation Army”) (Donghai shilu bianzhuan weiyuanhui 1998: 97), and soldiers stationed at Xiju by the mouth of the Min River, who were posed to launch guerrilla warfare at any moment. Since the KMT government offered almost no provisions at that time, the soldiers behaved much like the bandits of the past, plundering shipping vessels to survive (226–8). With the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950, the United States established Western Enterprises Inc. (Xifang gongsi) in Taiwan in 1951, a Western outfit that was designed to spy on the enemy and to carry out guerrilla warfare in order to contain the People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) military strength and to prevent it from dispatching forces along the southeastern coasts to fight on the Korean peninsula. The company operated under the auspices of the CIA and established a liaison station in Xiju, collaborating with the East China Sea Fleet in attacks on coastal China (Holober Reference Holober1999). The company closed down when the hostilities ended, and the East China Sea Fleet was absorbed into the KMT armed forces in 1955. Although the USA Military Assistance and Advisory Group still maintained a base in Nangang, they withdrew completely in the 1970s.1

After repeated losses in the series of battles between the KMT and the CCP on the southeastern islands, the KMT government was left holding control over only two island areas, Jinmen and Matsu. With no end in sight to the standoff between the KMT and the CCP, Chiang Kai-shek implemented military rule over the frontlines of Jinmen and Matsu in 1956. The Warzone Administration (hereafter WZA) was a centralized military administration, subordinating civilian affairs to the military command. It took centralized orders from the highest military commanding officer on the islands, unifying the whole society and the lives of citizens under military rule (Guofangbu shizheng bianyiju 1996: 96, 109). It was originally employed during the war to govern occupied territories and newly recaptured territories, and it was designed to control manpower and resources within military zones for the benefit of the military (8, 101). Since Jinmen and Matsu were on the frontlines of the conflict between China and Taiwan throughout the 1950s, Chiang Kai-shek chose these two areas as a “testing ground” for military administration.

From the point of view of the government, over the short run the implementation of the WZA in Jinmen and Matsu could provide a protective screen across the Taiwan Strait. In the long run, it was hoped that political, economic and cultural development of these warzone areas would be carried out under military control. With the ideal “to administer, instruct, enrich, and secure” (guan, jiao, wei, yang) (190), the military army aimed to transform Jinmen and Matsu into “a model county for the Three People’s Principles” (sanmin zhuyi mofan xian) in the Republic of China.

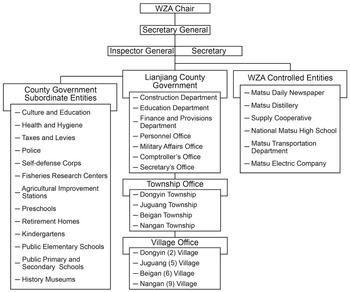

The WZA was led by the committee chair, held by the islands’ highest commanding officer, with a secretary-general under him, held by the director of the Office of Political Warfare. The Warzone Administration Committee (WZAC) consisted of five to seven members and had jurisdiction over the Liangjiang county government. On the premise that the military would govern civil affairs, the WZAC was responsible for governmental policies and supervision, while the county government was responsible for the planning and implementation of those policies (Fig. 2.1).

Fig. 2.1 Matsu Warzone Administration Organization

In addition to WZA organs, the military had other ways of managing the villages. Each village head was selected by the WZA, and a deputy village head (also known as a political instructor) was sent by the military to supervise and oversee village affairs. The military also had a hand in the lives of individuals: locals were armed and organized into civil defense units. Every man between the ages of 18 and 45 and every woman between the ages of 16 and 35 had to participate in four weeks of training twice a year.2

From the above description, we can see that the WZA produced a system in which the military had full command of the local people and their resources. It was, first and foremost, a systematic administrative system commanded by the military. Second, it reorganized the people into civil defense units to assist in the war effort. Third, it controlled the resources of the islands with the establishment of the “Supply Cooperative” (1953) and the Matsu Distillery (1956), which brought the consumption and circulation of goods under government management. Finally, the military state also published a local newspaper, Matsu Daily (starting in 1957), to promulgate government orders and enforce ideological control. Overall, the WZA or military governance represented a kind of militarized modernism (Moon Reference Moon2005; Szonyi Reference Szonyi2008): power plants, water reservoirs, hospitals, and schools were set up on each island. Many modernizing projects of farming, forestry, fishery, and animal husbandry were implemented to make the best use of the people and resources within the warzone.

The establishment of this particular administration had its own historical basis and objectives. Szonyi’s (Reference Szonyi2008) research on Jinmen builds on the geopolitics of the Cold War and greatly clarifies the significance of Jinmen and Matsu with respect to America, Taiwan, and China. When the Korean War broke out, the American president Harry Truman declared a “neutralization of the Straits of Formosa” in order to cool hostilities between China and Taiwan. In 1958, America and Taiwan signed the “ROC-US Mutual Defense Treaty” to work together to prevent the spread of communism, but the treaty did not extend to Jinmen and Matsu. In 1979, when the US and China established diplomatic relations, America abrogated its mutual defense treaty with Taiwan. Although America agreed to sign the “Taiwan Relations Act” to help Taiwan to protect itself and to consolidate its East Asian line of defense in the Cold War, the position of Jinmen and Matsu was left unclear.

For Chiang Kai-shek, Jinmen and Matsu had great significance. Located in the southwest and northwest parts of the Taiwan Strait, they could block Taiwan’s access to Xiamen, Fuzhou, and Sandu’ao (Guofangbu shizheng bianyiju 1996: 193). The islands were also of military importance in other ways. They allowed outposts of soldiers to carry out intelligence gathering and guerrilla warfare, as well as preparation for PRC counterattacks. Because they were so close to mainland China and had once belonged to Fujian province, their very existence as such could be claimed as evidence that Chiang Kai-shek was still in control of “China” (and not just of Taiwan). Chiang Kai-shek also believed that the strategic importance of Jinmen and Matsu could actually ensure America’s continuing support for Taiwan (Szonyi Reference Szonyi2008: 43). It was for these reasons that Chiang tried to construct an image of Jinmen and Matsu as symbols of a global fight against communism.

In China, Mao Zedong considered seizing Jinmen and Matsu. However,

…by September [1958] Mao was confirmed in his decision that it would be counterproductive for Jinmen to fall to the PLA. The ROC presence on Jinmen was a reminder that both regimes agreed there was only “One China” that would one day be reunified. If Jinmen were to fall, it might be a first step toward the permanent separation of the two regimes, toward “Two Chinas.”

Therefore, from 1958 to 1979, when diplomatic relations were established between China and the US, the People’s Liberation Army engaged in a special “one day on, one day off” (danda shuang buda) battle tactic, which allowed the defending forces in Jinmen and Matsu a chance to resupply. This also served to remind the US and Taiwan that both Taiwan and the islands of Jinmen and Matsu belonged to China (76).

“One Island, One Life”

How did the implementation of military rule, and in particular, the WZA, influence Matsu? As previously described, Szonyi’s research on Jinmen, another frontline island of Taiwan, demonstrated how militarization (Lutz Reference Lutz2001, 2004) infiltrated every aspect of Jinmen, and how the local society—whether in terms of the labor force, material goods, minds and bodies—was gradually molded to serve military goals. To understand the effects of military rule on Matsu, it is therefore important to note that it had a very different history from Jinmen before the army arrived. A brief reminder of Matsu’s transient and fragmented past, discussed in detail in Chapter 1, will aid in our discussion.

Matsu before 1949 was a forbidden outpost and a stateless society. The first official administration over the area was established only in 1934; even so, the responsible officer sent to the island was killed by bandits in less than two years. Matsu was quite lawless in the early part of the twentieth century and hostage to violent clashes between pirates, bandits, and warring international forces. Before the arrival of Chiang Kai-shek’s army, there were few links between the villages of the Matsu archipelago; rather, each was connected to Fujian separately. The people at that time were often temporary residents during the fishing season: they described the islands as merely their “outer mountains,” while their real “homes” were on the mainland. Not only were they ready to return “home” at any time, many important rites were performed on the mainland. For this reason, inter-village interactions were limited, and even within each village, different neighborhoods often remained independent from one another.

The establishment of the military administration in Matsu was thus unprecedented and totally transformed the islands. On the one hand, modernizing projects including power plants, reservoirs, fishery and agricultural improvement centers were initiated to augment local production capacities; and a new Matsu currency and the Regulation of Goods Department directed the flow of money and goods. On the other hand, intensive surveillance, including household registration and regulation of people’s movements, as well as normalization, such as schooling and other ideological controls, were implemented at the level of the individual. The islands were thus brought totally and abruptly under military control.

The Matsu archipelago, however, is spread along a stretch of 54 km of ocean. During a war, contact between the islands could be easily cut off. Even more important than developing the labor and resources of Matsu was the need to foster a spirit of independence so that each island could carry on the war effort on its own. When the army arrived, they quickly constructed ring roads on all the islands; military trucks served as means of public transport, running between villages to encourage interactions between locals. Important intersections were festooned with spirited slogans, such as “One island, one life—the army and the people are one family,” to indoctrinate the population and to promote a sense of solidarity (Fig. 2.2). The army also published an island newspaper, Matsu Daily. A shared daily rhythm thus appeared; an idea of simultaneity, provinciality, and even a common fate among the islands had emerged. A new consciousness on each island, and also on the archipelago writ large, had arisen: Matsu had become an imagined community (Anderson Reference Anderson1991[1983]).

Fig. 2.2 A carved slogan erected beside a Matsu transportation hub: “One island, One Life”

The army’s large-scale modernization projects, from the paving of roads and island-wide forestation, to compulsory education, were jarringly new for the people who had long lived on the peripheral margins of the state. Since the Matsu Islands had always served as a temporary residence, the first facilities were rudimentary and shabby. The massive improvements of infrastructure, and the ubiquitous schools in particular, met with the people’s approval, to the extent that to this day they are grateful even today for the army’s contributions to these once-barren lands. Locals and soldiers gradually formed a sense of being “one community.” Although this concept was initially imposed by the army, it penetrated deep into the island’s social texture and the people’s minds.3 During this time, the islanders identified “Matsu” as a place of great military importance, “a springboard against communism” (fangong tiaoban), and “a protective shield across the Taiwan Strait” (taihai baolei), a notion which legitimized military control and justified the many sacrifices made by its people.

A Trail of Blood

Even so, it cannot be denied that the military state was an imposed power, one that was armed with physical and disciplinary force. How did the people of Matsu experience this abrupt intrusion? How exactly did this power weigh on individuals? The memories of the murder love triangle recounted above provides further clues.

The people of Matsu called the soldiers “lang a liang,” meaning “two different voices” in the local dialect, emphasizing the difference of their origins and languages from those of the islanders. The two men involved in the love triangle—the company commander, and Guoxing, who had been transferred there from Jinmen to work in the Matsu Distillery—were both outsiders. The new administration, the WZA, brought in such outsiders and set up institutions that had never before existed in these outlying islands. When locals recounted the event, they usually emphasized how Guoxing turned to different state institutions for help after he was injured: the port authorities, the county hospital, and the village administrative office (Fig. 2.3). This reveals how a once isolated world had by this time become a military state. The institutions Guoxing or the commander passed, such as the military intelligence post and the rice storehouse, had been set up as part of the war effort. These buildings obtruded everywhere in the village as physical manifestations of the intrusion of the military state in every aspect of life.

Fig. 2.3 The buildings and sites related to the crime4

The crime of passion also demonstrates how these state institutions were frequently inhumane and unconcerned with the plight of the local people. When Guoxing ran, dripping with blood, to the port authority to seek help, the soldiers made no attempt to assist him. He could only flee in a panic to the next place of possible aid, namely the army hospital. But since the military personnel there were regular nine-to-five workers, they had already gone home.

This story was narrated to me in detail by Cao Daming, who was fourteen or fifteen years old at the time of the murder. A child of a poor family, he began to work as a messenger boy for the local village office not long after he finished primary school. Encountering this tragic event at an impressionable age, he remembered it vividly, particularly the long trail of blood. The deputy village head was charged with investigating the causes of the murder and reporting back to the army. Cao accompanied him to examine the sites and timeline of the violent acts. That message boy is now over sixty, but he spoke of the events as though they had happened yesterday, becoming agitated and even beginning to stutter. When asked about his speech impediment, he answered that when he was a young boy, his family lived next to a room used for interrogation by the army, which often held “communist spies.” Curious, he would sometimes creep up to the room’s windows with his two brothers to watch the prisoners being tortured for information. He was still young and innocent at that time, and he and his brothers would imitate how the spies talked as they underwent water torture or were beaten:

I – I – I don’t know!

I – I – I really didn’t do it!

It – it – it really wasn’t me!

Even today, he and his brothers still have a slight stutter. The scars left by military rule have not healed.

I heard this story not long after arriving in the village. Startled, I decided to scrutinize how military rule had changed the lived world of the islanders.

Circumscribed Spaces

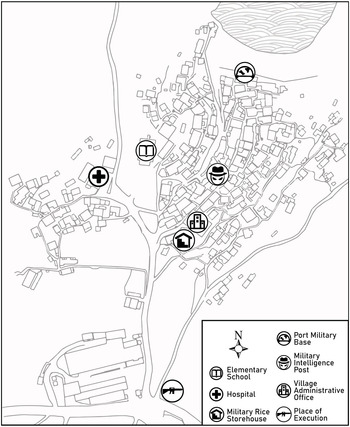

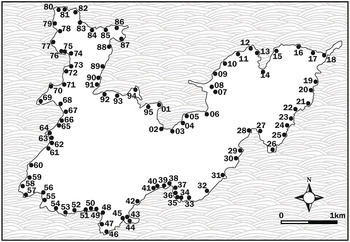

What followed the imposition of military rule was a general sealing off of the islands. The people of Matsu used to be able to move about freely, but soon each island was encircled by military bases. The coastline of Nangan, for example, had ninety-five coastal military bases and checkpoints keeping watch over the open sea (Fig. 2.4).

Each inlet and all of the coastlines had layer upon layer of military defenses. Inlets were fortified with anti-landing spikes and shards of glass, and both sides of promontories were dotted with hillside military blockhouses. This fortification of village inlets (Cheng Reference Chen2010: 74) not only cut the islands off from one another, but also cut the local people off from the ocean. The sea-going Matsu people, who liked to collect shellfish during low tide, now had to pass through layers of wire fencing and landmine zones in order to get to the shore where they then risked being driven away by soldiers. For years, the people of Matsu born during military rule grew up as strangers to the sea. Here’s how Xie Zhaohua, a local doctor, describes his experience as a child:

To me, the sea was always foreign. Though I could see it each morning when I left the house, I always kept my distance from it. It was foreign not because I couldn’t see it, but because there was no way to get close to it. Our teachers told us again and again not to approach the shores, especially areas surrounded by wire fencing, which meant that they were “dangerous landmine zones.” Those were forbidden areas, secret places, just like the many military encampments hidden in the mountains.

In this passage, Xie Zhaohua’s allusion to the “many military encampments hidden in the mountains” is worth examining. The memories of old residents as well as photographs from the period show that in earlier days, trees were very sparse on the islands and hillsides were covered with thick cogon grass. According to records from 1956, “the whole island had only about twenty banyan and other trees, and the bare hills were covered in pale sand” (Fujiansheng lianjiangxianzhi bianzuan weiyuanhui 1986: 471). Thick vegetation, however, could also provide camouflage for military encampments and helped to prevent enemy fire from reaching its target; moreover, military activity could be carried out in secret behind the tree cover. Given this necessity for concealment, the WZA began to carry out continuous “Matsu forestation” projects, implementing measures of “rewards and punishment to promote forestation” (Weihu shumiao 1961). The military at one point even decided that sheep were an impediment to forestation, and promulgated an edict ordering the “elimination of sheep” (Tan lühua 1962). Not content with forbidding the grazing of sheep, the army announced that any sheep found grazing outside the allowed areas could be killed by any person (Y. Li Reference Li1998: 49; B. Yang Reference Yang, Liu, Li and Lin2014: 271–2). Liu Hongwen’s article “Sheep,” describes an incident that occurred at the time between a group of Matsu school children and a sheep:

In those years, you would always see a few sheep around the islands, perching high up on towering ocean cliffs. …Some said that these were sheep that had been driven into the wild after the forestation projects and the prohibition on grazing. Others said that they belonged to noncommissioned officers who were raising them on the sly…. At that time, I was in elementary school, and each day I had to walk with some of my classmates down a mountain path to get to the school. …One day not long after we had left our village…we suddenly saw a frail-looking sheep on the mountainside to our left. It was nibbling at the grass and staring at us forlornly. One of us started shouting “baaaa baaaa”…and it lifted its head to look at us. We…gave the sheep a nickname, “White Whiskers.” Every day we hoped to see White Whiskers again. The bolder ones among us would even pull on White Whiskers’ beard and rub his belly. …Forming a relationship with White Whiskers became the most exciting event of our schooling.

One day we came home from school, and the atmosphere in the village seemed strange. The adults were all silent and mysterious…as though they were hiding something. Then…I went around to the back door of my uncle Jinquan’s house, and my eyes fell on the already-skinned body of a sheep…hanging bare and naked from the doorframe. …It was White Whiskers. In that difficult time of deprivation, especially in a poor remote village on an outer island, a meal of stewed mutton was a very rare pleasure. That night, the whole village was happy, and everyone got a share of the meat and organs. My family got a small portion of a leg. …I had no appetite. All I could think about was why White Whiskers had come down from the mountain. He had trusted us so much that he’d lost his wariness around the villagers. And when the villagers caught sight of him…

After the sheep disappeared, the forestation of Matsu proceeded apace. Today Matsu is completely green, and each island has more than eighty percent forest cover (B. Yang Reference Yang, Liu, Li and Lin2014: 272). However, this also divided the island’s high-altitude areas from its low-altitude areas; the difference between the military encampments concealed in the mountain forests and the exposed villages along the inlets was thrown into stark relief. The history of the development of the villages of Matsu cannot be separated from the fishing economy. The villagers were fishermen and built their houses first around the inlets and then expanded out toward the mountain cliffs. Outside of the villages, the mountains were covered in trees, concealing military bases, blockhouses and encampments. From above, the soldiers stationed in the woods could maintain a clear sense of what was happening in the villages.

Foucault’s (1977) concept of panopticon can help us understand the power dynamics of this spatial arrangement: the Matsu villagers below could not see the soldiers hidden in the mountain forests, but the soldiers above could tell at a glance what was happening in the villagers’ lives, even knowing the comings and goings of any given individual. If we return to the crime of passion and examine it in terms of its location—Ox Horn—we find that there were three nearby encampments placed above the village, from which each household could be seen clearly. In other words, the company commander need only look down from his encampment to apprehend what was going on with his lover and his rival and prepare to ambush them. After Guoxing was stabbed and fled, the company commander knew Ox Horn so well that he could infer the route Guoxing would take to try to escape and felt no need to pursue him. He need only wait at a major intersection for his rival to return exhausted and weakened. The company commander’s gaze in this incident thereby represents the state’s panoptical power. The state could observe every villager, while also remaining invisible to the villagers. As an agent of the state’s panoptical nature, the company commander both created and enacted the state’s potential to see and to know.

If Foucault’s concept of the “panoptical” can help us understand the spatial structure of the military rule over these islands, then the execution following the love triangle murders shows us an example of state ceremony. Geertz (Reference Geertz1980: 123) says that the state draws its force from imaginative energies. From this perspective, it is clear why the state decided to publicly execute the company commander. Indeed, the set up was a carefully staged state ceremony: the company commander forced to wear a placard inscribed with his crimes and paraded around the village, the execution grounds filled with somber military police, the six pointed rifles, and the WZA’s order to shoot to the death. Its goal was to display, defend, and reaffirm the state’s power. Ironically, only the patriotic slogan shouted by the company commander before his death revealed the real executioner behind the scenes.

Sailing through Liminality

As one can imagine, with the islands closed off from the outside world, border-crossing became very difficult. During the military reign, strict controls were imposed on movements between Matsu and Taiwan. The application process to leave was very tedious:

To board a ship, you had to have papers, formally called a “Republic of China Taiwan-Jinmen-Matsu Area Travel Permit.” First you went to a studio to get a headshot taken, then you had to fill out the forms, find a guarantor, and take everything to the village office. Your paperwork was checked at the local police headquarters before finally being sent on to the local command post. Every detail was inspected at each stage, and each step carefully controlled. …Then you had to wait…and when the papers were issued…you had to somehow get a berth on the ship. Sometimes there was space and sometimes there wasn’t. It all depended on what kind of connections you had.

Even after all of the aggravating paperwork, traveling by supply ship was a painful experience shared by nearly all the islanders. At that time, no civil vessels made the trip between Taiwan and Matsu, so Matsu residents heading to Taiwan had to take supply ships. A resident of Dongyin recalls that in the early days, a supply ship could take as long as a week to reach Taiwan: after leaving Dongyin, the ship first went to the administrative center in Nangan, and then headed back north to Beigan before proceeding to Dongju and Xiju. Only after it had circled all of the islands did it finally make its way to Taiwan. Although this detour was later shortened, one still considered oneself fortunate if one could make it to Taiwan within two days.

A long tedious journey was one thing, but what they encountered on the ship was really torturous:

On the day of the trip, we rose at dawn…it was drizzling, and people squatted in rows all along the beach, patiently waiting to be called onboard. The military police shuttled back and forth, checking our papers, ransacking our luggage…they went through everything and left behind a mess.

Finally, we were given the signal to board, and the crowd swarmed toward the mouth of the huge beast [ship], and found berths in the gloomy cabins that were filthy with cement, dust, rice bran, engine oil, and putrefied fruit. Many were left without a berth, and had to find a spot in a corner where they could spread out a mat or put down a piece of cardboard. This was where they would rock back and forth for eighteen hours.

The summer was easier, since people could be aboveboard on the deck…occasionally a wave would come up and slap their faces, and soon their eyes, faces, and arms would be covered in a thin layer of sea salt. Even the breezes were salty. …In the winter, the ocean wind was piercingly cold, and enormous waves would beat the deck while everyone hid in the hull and retched as the children wailed and the filth got worse and worse.

It was just as agonizing to come back to Matsu from Taiwan. Migrants returning to Matsu first had to register at the Jinmen-Matsu Guesthouse (Jinma binguan) in Keelung and then wait. Sometime in the afternoon, if the guesthouse posted a sign saying “Departures Today,” everyone would prepare to board with relief. If no sign was put up, they would have to return the next day. The Jinmen-Matsu Guesthouse was provided for soldiers to have a place to stay on those days when the weather was too poor for the ships to sail. In general, ordinary citizens had to return to their residences each day until they could leave. For young people in particular, who had very little money to begin with, going back and forth a few times would easily exhaust their funds. Cao Daming recounts how he waited once for seven or eight days until he ran out of money and decided to sleep in an empty freight truck parked near the Jinmen-Matsu Guesthouse with his teenage friends. He woke up to realize that the truck was driving south. It turned out to be a vegetable truck from a nearby market, and the driver had stopped to rest before leaving early the next morning to pick up more produce. When the driver realized he had stowaways, he scolded them and shooed them off. The penniless young men could only put their heads together and try to figure out a way to get back to Keelung.

The passage between Matsu and Taiwan was like a liminal period, in which both the body and spirit were tested and transformed. As Turner has stated: “[D]uring the liminal period, neophytes are alternately forced and encouraged to think about their society, their cosmos, and the powers that generate and sustain them. Liminality may be…described as a stage of reflection” (Turner Reference Turner1967: 105, original italics). This kind of reflection happened not only during the journey on the ship, but also became deeply ingrained in people’s memories. The local leaders examined in Part III frequently begin with their painful experiences of such trips when explaining the impetus behind their desire to change Matsu.

Conclusion: Imagined Community vs. Individual Suffering

In 1949, the army abruptly arrived in Matsu and indelibly changed the fate of the islands. This chapter analyzes how military rule transformed the lives of the local people from the perspective of space. I have demonstrated that once the Matsu archipelago became a frontline in the war, the close connections that had previously existed between the islands and the mainland were severed. The WZA carried out large-scale construction projects, propagated public education to modernize the islands, and also employed print media and local currency to create pan-island connections. As a result, “Matsu” became a newly imagined community, with a new social imaginary as a “fortress in the Taiwan Strait” and a “springboard for anticommunism.” This imaginary gradually became the identity of the Matsu people.

If we examine the lives of individuals more closely, however, we see a different picture. The state came from afar and penetrated every aspect of the islands immediately and deeply: all kinds of military institutions (such as port bases, intelligence posts, and rice storehouses) mushroomed, and became integrated into the living spaces of locals. In the hills above the villages were secret military barracks, with their constantly surveilling eyes: the oversight and control of the state was ubiquitous. Anyone wanting to enter or leave the islands had to brave the torture of travel by sea. The crime of passion, Cao Daming’s stutter, the schoolchildren who lost their beloved sheep, and the sense of being close to the sea but estranged from it—all these examples demonstrate how the power of the state permeated people’s bodies, minds, emotions, and knowledge, clashing with them and creating conflicts and trauma.

The impact on individuals and society when a place becomes a frontline is complex and intricate. In Chapter 3, I will explore this issue further from the perspectives of the fishing economy and gender relations.