This short note accompanies the excellent chapter by Mirza Hassan, Sayema Haque Badisha, Towid Iqram Mahmood, and Selim Raihan on the performance and governance challenges of banks in Bangladesh. In their chapter, the authors compare the bank performance of Bangladeshi banks with banks in neighbouring countries and across different ownership groups within Bangladesh. They also point to serious regulatory and governance challenges within the banking system. In this note, I will complement their cross-country comparison of financial sector development with a discussion of how to interpret different indicators and a benchmarking model. I will also offer a broader discussion of the factors preventing further financial sector deepening in Bangladesh, and I will conclude with some additional proposals for how to overcome the governance challenge in Bangladesh’ financial system.

Financial Sector Development in Bangladesh

An extensive theoretical and empirical literature has pointed to the critical functions of the financial system, including by (i) providing transaction services and thus enabling specialisation of labour; (ii) intermediating funds from savers to entrepreneurs; (iii) assessing investment projects ex-ante and monitoring borrowers ex-post, thus mitigating principal–agent conflicts; (iv) mitigating liquidity risks, allowing savers ready access to funds while enabling long-term investment; and (v) enabling investor cross-sectional and intertemporal risk diversification. An expansive literature has shown a positive relationship between financial development and economic growth, robust to reverse causation and omitted variable bias, and particularly strong in developing countries such as Bangladesh (see Popov, Reference Popov, Beck and Levine2018, for a recent overview).

One key challenge when assessing the relationship between financial development and real sector outcomes, as well as when comparing financial sector development across countries and over time, is how to measure the efficiency and development of a country’s financial sector. While theory points to specific channels and mechanisms, as discussed above, the empirical literature has not been able to map these different functions onto very specific empirical measures. Critically, several of these functions are complementary to each other: for example, the pooling and intermediating of savings goes hand in hand with the screening and monitoring of borrowers. Similarly, pooling and intermediating savings implies liquidity transformation. By offering payment services, banks learn about potential borrowers and thus get better at screening and monitoring them.

In the absence of variables capturing the individual functions of the financial sector, the literature has used crude proxy variables focusing on the size and activity of financial intermediaries and markets, most prominently private credit to GDP, which is the total claims of financial intermediaries on domestic private enterprises and households in an economy, divided by GDP. By capturing the total amount of financial intermediation by regulated intermediaries in the economy, this variable proxies for the total volume of intermediation. The main advantage of this indicator is that it is available for a large cross-section of countries and over longer time periods, as the underlying data (total credit outstanding and GDP) go back until 1960 for many countries. Confidence in the measure is further increased as it is significantly correlated with other indicators of the efficiency of the financial system, available for fewer countries and over shorter time periods, such as interest rate spreads and margins.

While academics have focused mostly on the facilitating role of the financial sector, which consists of mobilising funds for investment and contributing to an efficient allocation of capital in general, policymakers have often focused on financial services as a growth sector in itself, as captured by the contribution of the financial sector to GDP. However, it is important to distinguish between the importance of the financial system within overall value added in an economy and the support that the financial system provides for the real economy. A larger financial system can both support the real economy but also be a burden on the rest of the economy, by, for example, drawing talent away from the real economy (Kneer, Reference Kneer2013a, Reference Kneer2013b). Based on a sample of 77 countries for the period 1980–2007, Beck Degryse, and Kneer (Reference Beck, Degryse and Kneer2014) find that intermediation activities increase growth and reduce volatility in the long run, while an expansion of the financial sector along other dimensions has no long-run effect on real sector outcomes. One specific example is Nigeria, which liberated its financial sector in the late 1980s. Very low entry requirements and the high market premiums that could be earned with arbitrage activities in the foreign exchange markets explained why the number of banks tripled from 40 to nearly 120 in the late 1980s, employment in the financial sector doubled, and the contribution of the financial system to GDP almost tripled. At the same time, however, deposits in financial institutions and credit to the private sector, both relative to GDP, declined (see discussion in Beck, Cull, and Jerome, Reference Beck, Cull and Jerome2005).

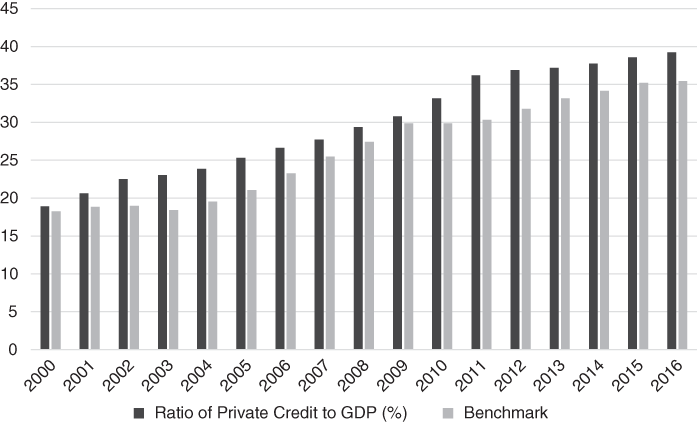

Comparing financial sector development across countries and over time is made difficult by different and changing socio-demographic structures. One way to address this challenge is to construct a synthetic benchmark based on a panel regression model of many countries over time (see Barajas et al., Reference Barajas, Beck, Dabla-Norris and Reza Yousefi2013 for further discussion). Among the explanatory variables included in this model are GDP per capita to proxy for demand-side effects, the young and old dependence ratio to proxy for demographic trends, total population to proxy for scale effects, and also year-fixed effects to control for global trends. This regression model makes it possible to predict financial sector indicators, such as private credit to GDP, for each country and year, and to compare it to the actual value. Figure 5.4 shows the actual and predicted value for private credit to GDP for Bangladesh for the years between 2000 and 2016. Strikingly, for all years, the actual value is above (though not by much) the value predicted by the socio-economic characteristics of Bangladesh.

Figure 5.4 Benchmarking private credit to GDP in Bangladesh.

What Drives Financial Sector Development?

Beyond socio-economic characteristics, financial sector development is critically influenced by the macroeconomic environment and the institutional and regulatory framework (see Beck, Reference Beck, Beck and Levine2018 for an in-depth discussion and literature review). I will discuss each in turn.

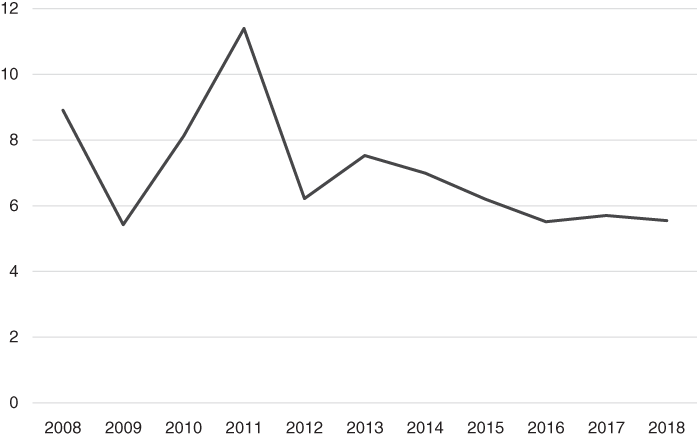

Bangladesh has a long history of macroeconomic volatility, as illustrated in Figure 5.5. While the inflation rate has been relatively stable (between 5% and 7%) over the past three years, going back further shows variation between 2% and 16%. Given the intertemporal nature of financial contracts, macroeconomic volatility undermines the appetite and willingness of both lenders and borrowers to commit to long-term contracts.

Figure 5.5 Inflation in Bangladesh (%).

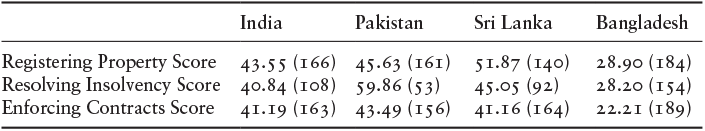

Given the intertemporal and often abstract nature of financial contracts, the financial system is also among the most sensitive sectors in an economy to the institutions of contract enforcement and property right protection. A second important area is therefore the institutional framework, which encompasses the rights of secured and unsecured creditors, the quality of court systems and efficiency of contract enforcement, and the existence and quality of collateral registries. Table 5.3 presents three indicators from the World Bank’s Doing Business database, showing the relative performance of Bangladesh compared to several other countries in the region. In most cases, Bangladesh lags behind the regional comparator countries.

Table 5.3 The institutional framework in Bangladesh

| India | Pakistan | Sri Lanka | Bangladesh | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Registering Property Score | 43.55 (166) | 45.63 (161) | 51.87 (140) | 28.90 (184) |

| Resolving Insolvency Score | 40.84 (108) | 59.86 (53) | 45.05 (92) | 28.20 (154) |

| Enforcing Contracts Score | 41.19 (163) | 43.49 (156) | 41.16 (164) | 22.21 (189) |

Note: The figure in parenthesis indicates the ranking out of 190 countries.

The Governance Challenges in Bangladesh’s Financial Sector

The situation as described in this chapter points to a lack of both market and supervisory discipline, and regulatory capture, not only by the state-owned banks but also by domestic private banks. Bank licences seem to be granted for politically connected entrepreneurs. There is a lack of de facto independence of the Bangladesh Bank, in addition to a long-standing ‘default culture’ (both for borrowers and banks), which explains the high level of NPLs. There is effectively no resolution of failed banks, but rather regulatory forbearance and recapitalisation. Finally, there is a lack of ‘reputational agents’, that is private institutions that provide information on bank performance and thus enable market discipline – except for the print media.

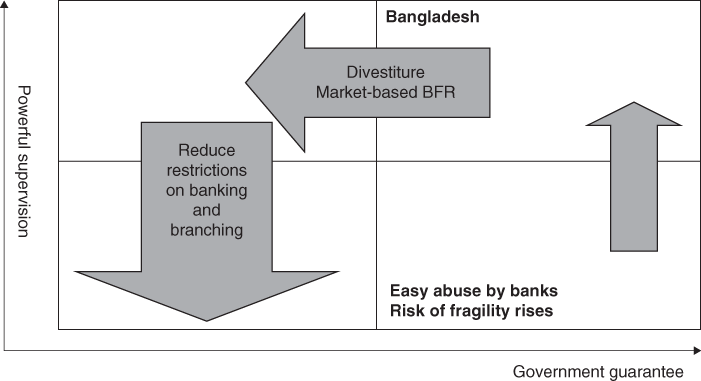

In 2006, I co-authored a paper assessing the development and stability challenges of the Bangladeshi banking system that painted a very similar picture (Beck and Rahman, Reference Beck and Rahman2006). One thing I noticed was that the financial and regulatory regime of high government guarantees and limited supervisory discipline resulted in high bank fragility. Moving to a regime with a stronger emphasis on market forces implies a carefully managed transition towards a more autonomous and powerful supervisory authority, privatisation of state-owned banks, and the establishment of a bank resolution framework, before one could move towards a more market-based banking system (Figure 5.6). In the 2006 paper, I made several policy suggestions, including (i) de jure and de facto autonomy of the Bangladesh Bank supervision from the Government, and (ii) complete divestiture of the Government from nationalised commercial banks. As Hassan, Bidisha, Mahmood, and Raihan eloquently describe, there has been no progress on (ii), and there has been a further deterioration in (i).

Figure 5.6 The interaction of government guarantees and supervisory approach.

What to Do?

The governance challenges in the Bangladeshi banking system call for strong policy responses. But it is important to understand that de jure reforms might not – at least by themselves – address the governance challenges. While privatisation of state-owned banks reduces direct government ownership, it does not address governance and efficiency problems in the private banks. Evidence from other countries (such as Mexico in the 1990s) has shown that privatisation to insiders can create new frictions and fragility. While a strengthening of the de jure autonomy of the Bangladesh Bank is laudable, its de facto autonomy is endogenous to the political structure of the country. And while de jure bank governance can be strengthened by legislation, enforcement is again endogenous to the political environment. Finally, a stronger stance against large and politically connected defaulters is necessary, but hard to enforce in the current political state.

I therefore make two suggestions that, though they might not have as strong effects, do take into account political constraints. First, foreign banks are less open to political pressure and can help break the link between politicians, borrowers, and bankers, as the example of Central and Eastern Europe has shown (see, e.g. Gianetti and Ongena, Reference Gianetti and Ongena2009). Foreign banks can certainly have their shortcomings, as they often lack incentives and knowledge to reach out to the most opaque and smallest borrowers; however, evidence from Pakistan has also shown that foreign banks from geographically and culturally closer countries are less subject to such constraints (Mian, Reference Mian2006). Second, strengthening private monitors (reputational agents) is an important reform item. Such reforms can include: (i) the creation of an FCA-style institution (separate from Bangladesh Bank) that focuses on bank conduct and supervision; (ii) steps to force more disclosure by banks beyond balance sheets and income statements, giving broader insights to depositors, media, and other stakeholders on their ownership structure and business; and (iii) improvements in the quality and governance of the accounting and auditing industry in Bangladesh. The latter can also include a mandatory rotation of auditors for banks.

Bangladesh has developed from ‘history’s basket case’ (as it was referred to by Henry Kissinger) to a rapidly developing and emerging economy, with aspirations of becoming a middle-income country. The banking sector has not yet played the role in this process that it can play. The necessary reforms are clear; what is less clear is how to overcome the political constraints in order to implement them.