I Introduction

The time has now come to put together what has been learned from the in-depth review of the economic and institutional aspects of Bangladesh’s development in the first part of this volume and from the in-depth study of key thematic areas in the second part. This diagnostic exercise will be presented in two steps. First, in Section II.E, a summary will be offered of each previous chapter, with the idea of stressing their most important messages in terms of the specific economic development constraints and institutional aspects of development to which they point. Second, in Section III, the diagnostic project will be presented. It will consist of three parts. In a first stage, an attempt will be made to identify the development-related institutional features that are common to all, or some subset, of the areas covered by the chapters in this volume. This exercise will allow us to see how a small number of basic institutional factors recur in multiple contexts in Bangladesh, and together condition and shape the development of the country. In a second stage, a reflection will be provided on the proximate and deep causes behind these factors. In a third and final stage of the diagnostic, directions for reforms that would correct weaknesses and/or enhance strengths will be explored. In this respect, part of the reflection will bear on how the implementation of these reforms may depend on deeper causes including the political economy context.

Four notes of caution are needed before proceeding with this final exercise.

The first note of caution relates to the somewhat exceptional character of Bangladesh, sometimes referred to as the ‘Bangladesh paradox’. More than is the case for most low-income or recently graduated low-income countries, Bangladesh’s development experience combines authentic successes, as testified by its rapid rate of economic growth over a little more than two decades, and major weaknesses, manifested most notably in key institutional areas. These weaknesses are sufficiently serious to threaten further development. Thus, in contrast with institutional diagnostics of less successful countries, the objective of the present exercise is not only to identify weaknesses that hinder further progress but also to understand how past successes relied upon specific institutional features that might either sustain or undermine future development. Among these features is the ability to circumvent ineffective formal institutions. The objective of the diagnostic is thus to highlight the causes of dysfunction, to uncover the inherent strength of the economic and social apparatus, and, possibly, to suggest ways they could be harnessed to correct dysfunctions and allow a sustainable and rapid pace of development.

The second note of caution relates to the intrinsic complexity of the relationship between institutions and development, and, more precisely, its circularity. The analysis conducted for the present institutional diagnostic focuses on one aspect of the relationship: the way institutional features affect development. Yet the opposite causality direction is equally important: development itself has an impact on the evolution of institutions. This aspect is especially important in the case of Bangladesh, where some of the deep factors plausibly influencing the nature of institutions and their capacity for reform today may precisely be related to the previous performance of the economy, notably in connection with ready-made garment (RMG) exports.

The third word of caution concerns the status of the reforms that may be considered as the natural outcome of an institutional diagnostic. Reforms that could improve the welfare of all actors in society would presumably have already been undertaken. Thus, the reforms that come out of a diagnostic exercise like the present one are unlikely to benefit all social groups. Hence an objection to the reforms suggested by the diagnostic will be that they are unlikely to attract a political consensus. Yet this does not make considering them any less important. On the one hand, identifying those social and political actors favouring a reform and those opposing it helps to clarify the political economy debate by better understanding the sources of resistance and, hopefully, the ways to surmount them. On the other hand, the distribution of political power within society may change in the future and reforms that are difficult today may become easier tomorrow. Therefore, a list of reforms resulting from the institutional diagnostic may usefully feed into the national public debate, even though their implementation may not be straightforward. We offer such a list in the annex to this chapter.

The last note of caution is about the COVID-19 crisis that struck the world and Bangladesh at the time the initial version of this volume was being finalised. There is no doubt that this crisis, above all its global economic consequences, has changed, and will continue to change the overall context of Bangladesh’s development. When this original version of this institutional diagnostic was concluded, it was obviously too early to be more precise. In the light of the information available today, we now suggest that the institutional weaknesses identified in this diagnostic will most likely become more significant in the new economic environment Bangladesh will face in the coming years. In fact, we argue further that those same institutional weaknesses have also been and still are critical determinants of the country’s limited ability to respond to the pandemic itself.

II Identifying Institutional Constraints in Bangladesh’s Development

As noted above, before presenting the institutional diagnostic, this chapter will provide a summary of the findings of previous chapters in the volume, in terms of the successes and failures of Bangladesh’s development, and their institutional roots. This is done in Section II.E. However, before embarking on this task, and to make this chapter self-contained, it will be useful to first briefly recall some key features of the political history of Bangladesh,Footnote 1 as several allusions will be made to them in Section II.E.

A A Sketch of Bangladesh’s Political History

The history of Bangladesh since the independence war with Pakistan in 1971 can be broken down into three eras, or three types of regime.

Although a democratic constitution, in the Westminster style, was adopted at the time of independence, the first 15 years of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh were extremely turbulent. The assassination of the founding leader, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, occurred within a few years and triggered a long succession of military regimes and coups. Out of this chaotic period came two main parties: on one side, the Awami League (AL), the party of Sheikh Mujib, which had played a leading role in pre-independence resistance against Pakistan; and, on the other side, the Bangladesh National Party (BNP), founded in 1978 by General Ziaur Rahman, then the president of Bangladesh. General Zia, as he was known, was assassinated in 1981 during a failed coup, and he was succeeded by General Ershad. The discontent of the population with respect to the military nature of the regime fed social unrest and eventually led to general elections being held in 1991, which were won by the BNP. A parliamentary constitution was then reinstated.

For the next two decades, the two main parties alternated in power, with the incumbent systematically losing to the opposition in the general elections that took place every fifth year. Throughout that period, the struggle between the two parties, and to some extent between their leaders, Khaleda Zia, the widow of General Zia, and Sheikh Hasina, the daughter of Sheikh Mujib, was intense. Democracy in that period was a kind of long winner-takes-all competition between the Awami League and the BNP, and virtually all means to destroy the opposition and to stay in power were used by both sides. Elections were so contentious, the temptation of rigging them so strong, and street violence so high in those periods that a non-partisan caretaker government was regularly appointed to ensure fair elections and to handle current affairs in particularly turbulent circumstances.

At some points, even the institution of the caretaker government was unable to comply with this task. In 2006, the BNP government was suspected of weighing in on the appointment of the caretaker government that would have to handle the forthcoming general election. The military had to come in to support a caretaker government, which took two years to organise the election and, in some instances, took initiatives that went far beyond this assignment. The Awami League won the election that finally took place in 2008 and has been in power since then. This was the end of the period of political alternance, often rightly termed ‘competitive democracy’ on account of the harsh political competition prevailing in those years.

Once returned to power, the Awami League was able to progressively impose full political control over the country. The institution of the caretaker government was made unconstitutional, and the BNP opposition was gradually silenced (this was partly its own fault since its failed attempt to disrupt the 2013 election through general protests and strikes eventually pushed it to boycott the election). As a result, the BNP lost a lot of political leverage, whereas the Awami League gained a ‘dominant party’ position and was able to weaken its opponent further, notably by having BNP leaders tried for and convicted of corruption. Consequently, the Awami League won the 2018 election with 289 seats – including 30 seats won by allied parties – leaving only 11 seats for the opposition, and six for the BNP. At the present time, the Awami League is thus governing without any real formal opposition, whether external or internal (since power has always been extremely concentrated within the Awami League party, as it is within the BNP).

This is where Bangladesh presently stands in its long quest for full democracy. It is difficult at this moment to predict what the next step will be. On many occasions a vibrant civil society in Bangladesh has shown its determination that the country become a true democracy. It is likely that opposition forces will reappear, based on the old parties or new ones, if the present party proves unable to maintain the fast rates of development that have been observed practically since the early days of the regime of competitive democracy. In this sense, the ‘dominant party’ era is best seen as a particular stage in the general evolution of democracy in Bangladesh.

B Successes and Challenges of Bangladesh’s Economic Development

Bangladesh has been able to maintain a rate of gross domestic product (GDP) per capita growth of between 4% and 7% over the last 20–25 years. Moreover, it has succeeded in more than halving extreme poverty since the turn of the millennium. Two key drivers are behind a large part of these remarkable achievements: the exports of the RMG sector, which have grown at an average annual rate of 12% since the late 1990s, and the remittances from Bangladeshi workers abroad, which have grown in real terms at a similar pace. It was estimated in Chapter 2 (Annex 2.3) that these two factors are jointly responsible for two-thirds of the country’s GDP growth. Increases in agricultural productivity account for most of the remaining growth performance.

The distinction between the two drivers of Bangladesh’s growth is important. The surge in RMG exports must be seen as the result of deliberate efforts to develop an internationally competitive manufacturing sector in this line of products. Bangladesh thus fundamentally differs from most countries at a similar stage of development, which have relied on more passive development strategies based on the export of primary commodities and which have therefore been highly vulnerable to strong fluctuations in world prices and demand. It is true that remittances from migrants suffer from the same vulnerability in Bangladesh, yet they have only been a secondary engine of growth. Unlike RMG exports, they contribute to overall growth essentially by boosting aggregate demand and therefore the sectors oriented towards domestic demand.Footnote 2 However, that the stock of Bangladeshis working abroad has been continuously increasing over the last 10–15 years is not a positive sign with respect to the capacity of the economy to absorb its labour surplus.

Another favourable aspect of development is the relative autonomy of the country with respect to external financing. Bangladesh’s dependence on foreign finance flows, most notably official development assistance, is much less than it was before the mid-1990s.Footnote 3 Because this reduced dependence is narrowly linked to the rising importance of foreign remittances, however, vulnerability to shocks in countries that host Bangladeshi migrant workers remains an issue, as illustrated by COVID-19.

Apart from the successful development of manufacturing exports, Bangladesh exhibits many of the characteristics and weaknesses of less dynamic, low-income or low middle-income countries. This is most notable when considering the size and low productivity of the informal economy, as well as the size and role of the public sector. Atrophied by an exceptionally low average tax rate, a restricted fiscal space hampers the delivery of public goods in desirable quantities and of desirable quality, and, in particular, slows down the accumulation of infrastructure and human capital that are required for sustainable development. In addition, the civil service is not working properly and is highly corrupt, the business environment is poor, and the regulation of the economy, including taxation and the supervision of the banking sector, is dysfunctional.

Social development appears better, but from the public policy point of view, it also shows weaknesses. Whereas undeniable, and in some respects impressive, progress has been made in primary school enrolment, partly thanks to an early conditional cash transfer programme,Footnote 4 levels of learning achievement are unsatisfactory. Public healthcare expenditures are extremely small. In these social areas, the failures of the state have been partly compensated for by an extremely dynamic non-governmental organisation (NGO) sector that has gained global recognition. Yet achieving real social progress that covers the whole population depends on adequate public policies. In brief, there is a real discrepancy between Bangladesh’s growth achievements through the RMG sector, on the one hand, and the situation of the rest of the economy, as well as social achievements, on the other.

These weaknesses might soon become of even greater consequence, as Bangladesh confronts major challenges in trying to maintain its development momentum in a global context very much affected by the economic consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic. As a matter of fact, the growth rate of RMG exports – as well as that of remittances – has slowed down over recent years, even before COVID-19. The same is true of agricultural productivity.Footnote 5 GDP growth rate in Bangladesh, though still positive, dropped by around 5 percentage points in the 2020 COVID-year. Also, total exports declined by around 17%. Several threats hover over RMG exports, including growing competition between low-wage countries, rising mechanisation that reduces the comparative advantages of developing countries, stricter regulations of labour conditions imposed by foreign clients, and the loss of least developed country (LDC) trade preferential status with advanced countries. It is thus far from certain that Bangladesh will be able to keep on increasing its global market share in RMG. Since there is additional uncertainty about – or at least significant variability of – the volume of foreign remittances, expanding exports through diversification, both within and (most importantly) outside the RMG sector, has become essential for sustaining the country’s development momentum. Such a strategy requires adequate measures and a well-articulated industrial policy, which is presently missing. The need for diversification is recognised in several official planning documents, but the strategy for reaching that goal is not well designed or implemented. The reasons for this situation will be analysed later.

C Bangladesh’s Institutional Performance in Global Rankings

As discussed above, Bangladesh experienced turbulent political times between independence and the early 2000s. Most indicators describing the institutional environment and the political and socio-economic conditions of the country show a strong overall improvement has taken place since then.Footnote 6 Even an indicator measuring the control of corruption has improved. Yet the broad picture is much less encouraging when we compare Bangladesh to other countries today, even when the comparison is restricted to developing countries.

According to most synthetic institutional indicators, Bangladesh is in the bottom 20% of global country rankings for all institutional dimensions, and even in the bottom 10% for some of them. Despite its growth performance, it is behind – on all dimensions – many developing countries with a comparable, or even lower, GDP per capita.

This disappointing performance is not uniform, though. If Bangladesh appears as particularly weak in areas like ‘bureaucratic quality’, ‘rule of law’, ‘land issues’, and, to a lesser extent, ‘human rights’, its relative performance is less disappointing in regard of the democratic functioning of the country and the business environment it offers to investors. It is interesting that these relative strengths relate to two key features of Bangladesh’s development: the maintenance of political stability over the last 10 years or so, and the surge of manufacturing exports in the RMG sector since the turn of this century. This observation may raise some questions about the causality of the relationship between institutions and development. Indeed, relatively better achievement on the business environment are likely to have resulted from the success of the RMG sector, rather than having caused the latter.

These rankings must be viewed with some caution, though. On the one hand, Bangladesh does not appear to be fundamentally different from other countries when the ranking is made conditional on the level of development.Footnote 7 If it underperforms relative to other countries in most areas, this is often by a narrow margin. It even does better with respect to the business environment. On the other hand, global indicators are rough measures of governance and institutional quality and may miss important details that might change the overall judgement to which they lead. In any case, it is largely on the basis of these indicators that the idea of a ‘Bangladesh paradox’ was formed: Bangladesh appears as a country with impressive economic growth performance but weak institutional performance. It is precisely because there can be some doubt about the reliability of institutional indicators in global rankings that we need a more detailed, and probably more nuanced, view, based on the sort of institutional diagnostic that is undertaken here.

D Bangladesh’s Institutional Performance Based on the Views of National Decision Makers

To obtain an idea of how local decision makers assess their country’s institutions, a Country Institutional Survey (CIS) was administered to a number of selected decision makers in various areas of activity: business, farming, politics, academia, the judiciary, the army, and civil society.Footnote 8 The survey was complemented by interviews with top decision makers and policymakers, so as to provide more detailed insights about Bangladesh’s institutional functioning. Fortunately, key opinions on institutional strengths and weaknesses expressed in the survey and the views and recommendations of top stakeholders in open-ended discussions proved to be broadly consistent with each other.

In the first place, it should be stressed that the CIS resulted in a ranking of problematic institutional areas similar to the one derived from exploiting cross-country institutional indicator databases. In broad accordance with the picture emerging from the global indicators describing the democratic functioning of the country, the two areas found by the respondents to be the least unfavourable to Bangladesh’s development are the business environment and the political system. This convergence between the views of insiders, that is local decision makers, and those of the international experts behind the cross-country indicators, is rather reassuring as it suggests that both approaches to detecting institutional strengths and weaknesses are credible.

The identification by survey respondents of problematic institutional areas did not prove to be particularly informative, because of rather small differences in their assessment across areas. Detailed evaluations of each area in the survey were much more informative. Respondents clearly put the ‘civil service’ and the ‘treatment of land issues’ at the top of the list of ill-functioning institutional areas, closely followed by the ‘political and administrative management’ by the executive.

Interesting results were obtained from questions related to specific sub-domains. The following weaknesses were especially stressed by our respondents:

ubiquitous corruption (electoral, business, recruitment to the civil service);

executive control over legal bodies, the media, the judiciary, and the banking sector;

inadequate coverage of public services;

the number and intensity of land conflicts; and

gender discrimination.

Some institutional aspects were found by the respondents to be rather satisfactory, though not always without some contradiction with other judgements. Among them were the development of a middle class, a feeling of national pride, the quality of public policymaking, and the positive role of informal arrangements. The latter’s importance was emphasised with special force, particularly in regard to dealings with the administration and the enforcement of contracts. In these two domains, informal channels and procedures were deemed to provide an effective alternative to deficient formal channels. This assessment fits well with the expressed distrust of central institutions, such as the judiciary, and the repeated denunciations of corruption.

Finally, the opinions expressed by key informants generally confirmed those of the CIS respondents. This is particularly evident in the fact that the former emphasised the low administrative capacity of the Bangladeshi state, corruption, and the ineffectiveness of the judiciary. But these informants also enrich our knowledge by pointing to sectors of activity where those weaknesses were considered by them to be most salient. Of special importance here is their emphasis on the weakness of industrial policy and the resulting lack of diversification away from the RMG sector, allegedly because of the disproportionate influence of the RMG’s business elite. The weak regulation of the banking sector, as evidenced by the pervasive and growing incidence of non-performing loans (NPLs), and the lack of autonomy of the Central Bank are other severe institutional flaws that negatively affect efficiency in this key sector of the economy. Failures in the way land conflicts are handled by the state and its administration are also revealing of a missing sense of direction on their part, with negative consequences for land allocation from the double standpoint of efficiency and equity.

E Some Critical Areas

Chapters 4–9 consist of thematic studies that focus on specific areas that were found to be critical on the basis of Chapters 2 and 3. For reasons of space, these areas do not cover the whole range of issues that were pointed to by CIS respondents and key informants. They were chosen because they are of direct importance for development per se, or because they provide a focus on the working of specific institutions. These areas are as follows:

the RMG sector, and the difficulty of diversifying manufacturing exports;

the failure of the regulation of the banking sector, and the problem of NPLs

the design and collection of taxes;

primary education as a major component of public expenditures;

the management of land issues, including the special economic zone (SEZ) policy; and

the judiciary and the treatment of land litigation cases.

In Sections II.E.1–II.E.6 for each in-depth study, a brief summary is offered of what they reveal about the functioning of Bangladeshi institutions, the root causes of their inadequacy, or (in some cases) the way their weakness can be bypassed, and their development consequences.

1 The Success of the RMG Sector and the Failure to Diversify Exports

How was Bangladesh able to increase the volume of RMG exports from virtually nothing in the early 1980s to a total value of US$ 30.6 billion in 2017/18 – becoming, in the process, the second largest exporter of RMG in the world? What were the institutional arrangements – both formal and informal – which facilitated this remarkable transformation and which made the RMG sector such a powerful driver of economic growth, and, reciprocally, how has the growth of the RMG sector itself affected Bangladeshi institutions? And, perhaps most importantly of all, what does the future hold for the sector and the economy as a whole?

This concern about the future is fundamentally a question of sustainability. It reflects an awareness that the growth of the RMG sector was driven by a number of opportunities and advantages, each of which is under severe and increasing pressure. These include international trade agreements, Bangladesh’s preferential LDC status, a political economy environment that, though clientelist, was nonetheless competitive, a suppressed labour regime, and simple, labour-intensive technology.

But, as emphasised in both the chapters by Selim Raihan and in the comments by Jaime de Melo, there are further concerns about the RMG industrialisation model itself, and in particular the (lack of) export diversification. Indeed, it is argued that the strength of the RMG sector not only reflects the weaknesses of other sectors but is, in fact, also a cause of those weaknesses. It also fundamentally calls into question the pathway of industrial development and structural transformation that Bangladesh has embarked upon. Is Bangladesh’s lack of export diversification a symptom of a deeper malaise – a set of institutions which may have generated success in the past and yet may now be acting as powerful constraints on development in the future?

Three main economic outcomes of the surge of the RMG sector are highlighted in the chapter by Raihan. The first of these is the structure and performance of the sector itself, both in terms of the growth of the sector and the nature of its production (e.g. the changing composition of products from woven to knitwear) and the production process (e.g. the adoption of subcontracting, the current trends towards labour-saving automation, and the low-value and basic quality of much of the production). The second is the way in which the sector dominates Bangladesh’s export basket, and how weak other sectors have been: it is striking how Bangladesh’s export concentration is higher than that of other country groups, and significantly less diversified than developing manufacturing exporters, and, in fact, not more diversified than some low-income commodity exporters. And the third and final observable outcome is the quite extraordinary management of the labour regime in the RMG sector, in which long working hours, low wages, a lack of regular contracts, and systematically hazardous working conditions are commonplace – as dramatically illustrated by the Rana Plaza disaster.Footnote 9 Trade unions have been suppressed and union organisers intimidated: wage negotiations, such as those conducted through the Wage Board, do not have proper worker representation.

The institutional issues behind these economic and social consequences are complex. The RMG sector was able to benefit from the presence of certain institutions and to exploit the absence of others. The growth of the sector was, in the first instance, crucially dependent on the international trade regime in textiles and clothing, such as the Multi-Fibre Agreement (MFA) system of quotas. This not only created reserved market opportunities for Bangladesh and other countries but also provided incentives for international collaboration – with South Korean companies, for example. Over time, the sector became extremely competitive and was able to regularly increase its share of the global market. To achieve these results, it was able to obtain a series of favourable ad hoc measures from successive governments – these included export performance benefits, the bonded warehouse system,Footnote 10 subsidies of various kinds, tax exemptions, export credit guarantee schemes, and export-processing zones. In effect, the RMG sector was, for several decades, the primary focus of Bangladesh’s de facto industrial policy, thus leading to a remarkably high degree of export concentration. From the outset, the RMG sector also crucially benefited from the absence of vigorous formal institutions that could defend industrial labour rights. This privileged status has continued during the COVID-19 episode, with RMG able to monopolise the benefits of the government’s economic stimulus package, and to successfully lobby for the reopening of factories and suspension of lockdown measures so as to minimise the disruption to the industry.

The evidence suggests that the very same institutional features which enabled the growth of the RMG sector are missing in other sectors – that there is not the same organisational capacity for industry leaders to participate in collective bargaining with the state, while key policy instruments are biased in favour of RMG and against other sectors, such as leather: think of the bonded warehouse scheme, or of the exchange rate policy, which has not been used to help industrial diversification, or indeed the policy response to COVID-19, which did very little to help MSMEs, in particular. It may also be the case that rent opportunities comparable to the MFA environment in the development of the RMG sector are not available in other activities, in which case they might have to be provided through a consistent industrial policy. However, in a time when the dominant RMG sector is experiencing several weaknesses and facing serious challenges, its politically powerful business class may not agree with, and may even block, any change in the present informal policy framework.

Despite the fragility of the current situation, this diagnosis of Bangladesh’s industrial development demonstrates many important points. First, the successes of the RMG sector show that Bangladesh has developed and retained significant organisational and firm capabilities, as well as an entrepreneurial class. However, it must now channel those capabilities into other sectors. Second, it shows that industrial policy within a ‘deals environment’Footnote 11 can be highly effective at an initial stage of industrial development, but care must be taken not to consolidate existing patterns of rent-seeking within a single sector, but rather to support dynamism and innovation. Third, transparent and non-politicised formal institutional structures responsible for industrial policy are needed to achieve this. They were – and still are – missing in Bangladesh. And fourth, if economic development is possible within a mostly informal institutional environment, such a context is inadequate as regards establishing and maintaining a social contract by which all stakeholders, including workers, commit to well-defined development strategies and are guaranteed to receive their fair share of the benefits. Such a contract is necessary for the long-run social sustainability of development strategies and requires formal institutions rather than an informal set of deals, even if the latter have proven temporarily successful.

2 Governance Failures and the Political Economy of the Banking Sector

At intermediate stages of development, the banking sector is of crucial importance through the role it may play in collecting savings and efficiently allocating investment resources in the economy. Bangladesh is at a stage where the sector, which was initially completely state-owned, has been substantially privatised, and several new banks have recently been licensed. Yet some important banks or financial institutions remain in the hands of the state, leading to a kind of dual structure of the whole sector. If, overall, the sector has been, and still is, effective in supporting the development of the RMG sector, it also shows major weaknesses and exhibits serious failures of regulation, most notably apparent in recurrent excessive NPLs. Often caused by fraudulent behaviour rather than problems of profitability, NPLs exert adverse effects on the efficiency of the economy, reinforce the culture of corruption in the country, and contribute to rising inequality.

The chapter by Hassan, Bidisha, Mahmood, and Raihan provides an overview of the performance and challenges of the banking sector in Bangladesh by looking at its structure, several financial performance indicators (including the NPL ratio), the efficiency of private banks, and the development implications of weak institutions. This chapter also explores the political economy of the whole sector and examines types of governance failures. The comments by Thorsten Beck emphasise key reforms needed in the governance of the sector, including the full de jure and de facto autonomy of the central bank – the Bangladesh Bank – and the divestiture of the Government from nationalised commercial banks. He observes that policy suggestions were made in the mid-2000s in that direction, but as confirmed in the chapter by Hassan et al., no progress was made, and the situation even became worse.

If the banking sector apparently provides a volume of credit to the economy that seems comparable in relation to GDP to levels observed in comparator countries, its management performance is mediocre. In 2017, Bangladesh ranked 147th out of 179 countries according to the international Z-score, an indicator of the probability of default of the whole banking system. Its Z-score was also the lowest among the South Asian countries. This bad performance is related to the low quality of the sector’s lending operations. Through regulatory and policy capture, political patronage often leads to unproductive loans, or simply loans that bankers know will never be repaid. Also, cases of embezzlement through legal insider lending – i.e. to the bank’s owners or their family – have been reported. NPLs, and the frequent need for monetary injection in state-owned banks or bailouts of private banks, are the manifestation of these governance failures of the whole sector, foreign commercial banks aside.

It may seem surprising that, despite these major weaknesses, the banking sector was able to financially support the major driver of the economy, the RMG sector, in the first place. RMG firms, as well as certain big import-substituting industries – for example cement, steel, and textiles – received a significant proportion of the loans disbursed. These loans, most often granted with extremely favourable conditions, are another example of the sort of ‘deals’ made between powerful entrepreneurs and the banking sector, possibly under the pressure of the political elite. Meanwhile, other export-oriented non-RMG sectors, such as the leather and the agri-processing sectors, faced difficulties in securing bank loans, or obtained them but with much harsher conditions attached.

NPLs have been a major concern in the banking sector ever since independence. They represented 25% of outstanding loans in the early 1990s, but that rate exploded at the end of that decade, reaching 41% in 2000. Effective reform measures were then taken, in part under the pressure of the International Monetary Fund, but also as part of an anti-corruption policy led at that time by the BNP government. The ratio was successfully brought down to around 6% by the late 2000s, but it increased again and has practically doubled since then. Initially, NPLs tended to be concentrated in state-owned banks, but in recent years, they have been on the rise in private commercial banks too. Besides affecting banks’ prudential ratios, they contribute to higher interest rates, and reduce private investment, outside the sectors that benefit from favourable deals. Overall, this situation undermines the prospects for export diversification, as well as future economic growth, in a non-negligible way.Footnote 12

A major institutional weaknesses of the banking sector in Bangladesh is the lack of autonomy of the central bank in regulating the sector, because of the clear subordinate position of the governor with respect to the Government and, through political links, private bankers. As a result, regulation is essentially ad hoc, implying that most often required action is not taken against malpractices committed by commercial banks. Dual authority in the banking system, by which state-owned banks are governed by the Banking Division of the Ministry of Finance and private banks are under the purview of the central bank, is another factor leading to ineffectiveness in the regulation of the whole system. There are also issues with the rising political influence of the BAB, the Bangladesh Association of (private sector) banks. The recent amendment of the Banking Company Act, which provides for the removal of several constraints governing the boards of private banks, reflects this influence.

With the emergence of COVID-19, a further consequence of the institutional weaknesses in the banking sector has become apparent – namely, the significant problems Bangladesh has experienced in disbursing funds, both to support firms and as social protection for vulnerable households. These issues – and the inequalities they expose, in the sense that smaller firms and the poor are disproportionately affected – continue to skew the recovery.

3 Taxation and the Difficulty of Tax Reforms

At 8.6%, Bangladesh is among the countries with the lowest overall average tax rate – that is the ratio of tax revenue to GDP. It follows that its fiscal space, that is the capacity to spend on public goods and correct rising income inequality, is extremely limited. The low average tax rate results from both low nominal tax rates and a low rate of tax collection, itself due to pervasive tax evasion (often with the paid support of tax collection personnel) or to tax exemptions generously granted by the Government to its supporters. In addition, albeit in a limited way, taxation distorts economic incentives, either directly through non-uniform tax rates that favour some sectors or firms and penalise others, or indirectly through exemptions and evasion.

The chapter by Sadiq Ahmed on taxation identifies and evaluates the institutional causes of these failures of the tax system. It also explores the reasons behind the difficulties that have surrounded previous attempts at tax reforms and the underlying political economy factors. It finally lists the most attractive reforms in terms of increasing tax revenues, the effectiveness of tax collection, and the redistributive impact of the tax system.

Tax revenue represents a little less than 90% of the Government’s revenue in Bangladesh. Over the past decade, tax revenue in proportion to GDP has slightly declined and, as just mentioned, has remained well below international norms, that is less than 9% (vs. 17–18% on average in developing countries). Such a low tax rate, and the low level of non-tax revenue, severely constrains public expenditures, which, again by international standards, are extremely low, particularly with respect to education and public health. The gap between total expenditure and total revenue is actually widening, forcing the Government to increasingly borrow from the domestic economy, with the risk of causing a crowding-out of private investment.

With the present tax to GDP ratio, the Government is unable to spend as much as needed on social sectors or on infrastructure – a situation that seems likely to worsen due to COVID-19. For quite some time already, a political consensus seems to have emerged regarding the dire need to increase taxation. The recent Government’s long-run plan, the Perspective Plan 2041, even includes doubling the tax to GDP ratio over a 10-year period. However, no progress has been recorded so far. Worse, a well thought out reform of the value-added tax (VAT) was buried several years ago.

Low administrative capacity, limited technical innovation (digitalisation), a high degree of administrative fragmentation, significant human resource constraints, tax evasion, corruption of officials, and strong lobbying by business to obtain exemptions are the main problems responsible for the low level of tax collection in comparison to the revenue that would be obtained with full compliance. The actual revenue of VAT among registered firms is only 12% of its nominal potential. The proportion is only between 20% and 30% for personal income tax, since many potential taxpayers, including many ultra-rich people, remain outside of the tax net or pay very few taxes. Likewise, numerous firms or economic sectors that can well afford to pay the corporate tax are either fully exempted or enjoy substantially reduced tax rates.

If tax collection is one obstacle to higher tax revenues, the structure of taxation is another. This structure distorts economic decisions and the allocation of resources, and, in some cases, discourages compliance. For instance, the multiplicity of corporate tax rates may give wrong incentives to investors – although effective rates may differ substantially from official rates because of special deals between business managers and the state. The income tax return process is unduly complex, with a marginal tax rate that depends on the wealth of the taxpayer. The VAT rate is 15%, but 10 lower rates are in place for specific services.

Tax policies should aim at horizontal and vertical equity: individuals in similar financial circumstances should be taxed at the same rate, and individuals with different abilities to pay should be taxed at a rate that increases with their income. In Bangladesh, the culture of tax avoidance works against horizontal equity, whereas the heavy reliance on indirect taxes and the pervasive incidence of income tax evasion cannot prevent vertical equity from declining or income inequality from rising.

The failure of the attempt at reforming the VAT in 2012 illustrates the strength of political economy constraints on tax reform. The reform was quite advanced, and a law was even passed, to be implemented a few years later. At the last moment, however, the implementation was postponed under the pressure of the Federation of Bangladesh Chambers of Commerce and Industry. The postponement then proved indefinite – although a new reform is apparently being prepared although, according to experts, it is unlikely to be as effective.

The resistance to tax reform does not come only from politically powerful taxpayers: it also comes from civil servants in the National Board of Revenue (NBR), who do not want to lose their sources of rent: for instance, digitalisation and computerisation would prevent them putting pressure on taxpayers or offering them illegal rebates against the payment of bribes. In some cases, there may thus be a coalition of interests on both sides of the tax system against reforming it.

The reforms that are needed are well known. Christopher Heady gives a useful list of them in his comments on the tax chapter – for example, the advice to avoid in vivo contacts between taxpayers and tax collectors (!). Yet most of these reforms would likely meet resistance from the sort of coalition mentioned above and would therefore be blocked in the absence of a strong political will at the centre of government.

4 Primary Education

Primary education, which is the foundation on which the education system is built, has long been recognised, both in Bangladesh and internationally, as a key public policy priority. As such, spending on this area in Bangladesh represents a sizeable part of public expenditures. It also raises important institutional issues, some of them common to the delivery of public services in general. It requires effective mechanisms for the recruitment, training, and retention of teachers; the construction and maintenance of schools and other infrastructure; the design and implementation of the curriculum; the monitoring of progress, through inspections and examinations; and the creation of a learning environment.

Taking an institutional view of the education system, as in the chapter by Raihan, Hossen, and Khondker, is important for obtaining a proper understanding of the outcomes it produces and, more specifically, for determining whether the system actually delivers learning beyond immediate goals, such as increased enrolment. In this regard, Bangladesh’s impressive record of increasing enrolment and achieving gender parity is tempered by the growing body of evidence showing that learning outcomes for many of its children are very poor indeed, although not poorer than those for children in India or Pakistan, as stressed in Elizabeth King’s comments. This underlines the importance of looking in-depth at the components of the system and the way they work together, instead of relying exclusively on basic indicators, including enrolment and indicators measuring the nominal growth of the system. The main systemic challenges identified in the chapter can be categorised as: (i) a complex coexistence of various actors; (ii) challenges related to resources; (iii) challenges related to teachers and teacher management; and (iv) challenges related to the curriculum and teacher training.

Regarding the first of these challenges, there are significant structural problems in the education system, whereby multiple actors are often faced with confusing and sometimes conflicting divisions of responsibility. This applies not only to overall ministerial control, in which three main ministries and several smaller authorities have management roles with respect to primary schools, but also to the devolution of responsibility across central, regional, and local authorities. The presence of multiple actors in this complex system makes it difficult to establish clear chains of accountability. At the level of resources, it is striking that Bangladesh has one of the lowest rates of public expenditure on primary education in the world (at 0.81% of GDP, it is well below the South Asian average of 1.3%) and also one of the lowest rates of teacher pay (the ratio of average teacher salary to GDP per capita is just under 1 in Bangladesh, as compared to over 4 in rural India and slightly under 2 in Pakistan). If we go beyond these headline numbers, we quickly discover that there exist serious problems in teacher quality, qualifications, and motivation, as well as many infrastructural deficiencies, in the form of badly maintained schools and a lack of adequate teaching materials, in particular.

In terms of the mechanisms for teacher training and recruitment, there are numerous institutional problems, as reflected in bribery, nepotism, and widespread corruption, including undue political influence. The recruitment of teachers is often distorted by the selective leakage of written exams, while the payment of bribes often serves to decide which teachers will be transferred to Dhaka. As with other institutional areas in Bangladesh, such practices are enabled by a dysfunctional level of oversight, monitoring, and accountability, which they in turn reinforce. There are such low expectations as regards being held to account that corrupt practices, such as paying bribes to get a transfer, or other sorts of unacceptable behaviour (such as teacher absenteeism), are virtually normalised. Finally, among all the structural problems, there is the curriculum itself and its implementation through examinations such as the Primary Education Certificate (PEC). This exam-oriented focus, it is argued, favours rote-learning and drills and does little to encourage the development of creativity, a sense of criticism, and reasoning.

Although the problems in Bangladesh’s education system, and indeed in its public services more generally, are both severe and deep-rooted, there are various reforms which could and should be undertaken. The historically low budgetary allocation towards primary education suggests that an increase in resources to the sector ought to be a major political priority. Improving teachers’ pay and career profiles, in particular, should raise the overall level of candidates for teaching positions, even though, as stressed by King, such a measure should come with an adjustment in the structure of base pay, to guarantee efficiency gains. While increased resources as such will not solve all of the problems, the analysis identifies key areas in which they might generate the greatest effects, including ensuring teacher quality and motivation through improved salaries, career progression, and training; addressing the longstanding inadequacies in infrastructure; and investing in curriculum reform to move away from superficial certification towards a more substantive learning-oriented model. As with other areas of reform, the experiences of COVID-19 have only reinforced these conclusions – in trying to mitigate the negative impacts of school disruption experienced by a whole generation of children,Footnote 13 there can be few higher priorities than investment in education.

5 Institutional Challenges in Land Administration and Management in Bangladesh

Land markets raise important institutional issues in many developing countries but especially so in Bangladesh, as land is so scarce and the population is so large. Institutional problems may arise in two senses: first, land arrangements may function sub-optimally as a means of allocating land in an equitable manner and of securing property rights; and second, allocation of land between traditional and modern uses, such as agri-business or some other industrial activity, may be distorted. The chapter by Raihan, Jalal, Sharmin, and Eusuf analyses both aspects, making a distinction between the operations of institutions (e.g. politicised land administration) and their outcomes (e.g. inequitable allocation of land, constrained industrial development).

The most immediate institutional land issues are purely administrative: a lack of proper records, an absence of digitisation, poor levels of infrastructure, external administrative issues, such as the lack of coordination between ministries, administrative complexities, such as unidentified khasFootnote 14 land; lack of transparency and information; congestion of land disputes; and extended corruption in various forms.

In understanding why these institutional issues should be so persistent and difficult to reform, despite being so readily identified, it is necessary to look deeper into the specific historical and political context, in which the tension between equity and efficiency is a recurring theme. The historical context matters because the weaknesses in the current land administration system are, in part, a legacy of the piecemeal way in which the law evolved through the pre-colonial, colonial, Pakistani, and post-independence eras. The political context matters because at each stage in this process, land reforms have been subject to political pressure in their design and have generated political effects in their operation. Very often what this has meant in practice is that land reform has been intended to promote equity (e.g. awarding land to landless peasants) but has not been implemented fully or its implementation has been resisted or subverted by local elites. In some cases, land reform may have been used for political purposes (e.g. dispossessing indigenous people in the Chittagong Hill Tracts). The institutional issues regarding land reform are therefore inseparable from the political economy. However, although policy at a national level is important in institutional terms, it is at the local level that the most decisive institutional effects occur. Here we see something similar to the ‘deals environment’, in the sense that informal deals, involving low-level corruption, nepotism, and the interference of business elites acting through political parties, rather than formal management, underpin land transactions. Consequently, the process of land administration has not only been captured by elites but has also become resistant to change, as political elites have a vested interest in obstructing reform or effective regulation, and the more the system works in their favour, the greater their resistance to reform.

There is an inherent tension between the equity/distribution aspects of land reform and those of efficiency/growth, which can manifest itself in several ways. Although land regulation may be subject to capture by local elites, the main purpose of such regulation is to protect the rural poor through the securing of land rights. The extent to which it might result in smaller farms, and what effects the size of farms might have on productivity – as asked by Dilip Mookherjee in his comments – is one channel through which institutional problems relating to land might constrain economic development. Alternatively, the pursuit of economic objectives might distort the equity-promoting goals of land-allocating institutions. Fragmentation of landholdings also presents industries and investors with information problems in regard to purchasing land, when both the value of land and the identities of those who hold it may be hard to determine because of highly imperfect land operation registers. In some cases, coercion has been used to force unwilling sellers to sell their land – a practice that is not only unfair to the sellers but also biased in favour of those purchasers who possess political connections. The result may be the shutting out of investment by those who are deprived of the right connections.

Another important channel is the use of land itself for economic purposes, such as the promotion of agri-business or industrial development through the designation of SEZs. It is with the latter that the final section of the chapter by Raihan, Jalal, Sharmin, and Eusuf is particularly concerned, illustrating the link between land and industrial strategy. How are Bangladesh’s attempts to use SEZs in order to create an attractive investment climate, foster innovation and entrepreneurship, and diversify its economy, enabled or constrained by its land allocation mechanisms? This chapter offers a detailed analysis of these issues, especially through the mechanisms of land acquisition and compensation. As with the land management system, the institutional mechanisms of acquisition and compensation are subject to a range of corrupt practices, which in turn create vested interests that resist change and a bias towards politically connected purchasers, or towards those willing and able to pay bribes. Such an environment is inimical to a good business climate and undermines the strategic economic purpose of the SEZs.

In summary, the institutional issues that constrain both the equity and efficiency objectives of land management come, in the first instance, from inadequate and sometimes outdated administrative frameworks. There is little political will or state capacity to reform or effectively regulate these frameworks. In addition, the system is opaque – it is often very difficult to get accurate information, especially for the poor – and there is little transparency or accountability. These are specific political economy problems, often arising at the local level, in which informal deals substitute for efficient institutional practices, and have the effect of entrenching the political status quo. A range of institutional reforms are recommended, from updating and improving the land survey to digitising records, to achieving a higher degree of state coordination, and to improving the mechanisms through which compensation is awarded for land acquisition. Of course, the aforementioned political economy issues themselves constitute barriers to such reforms, as does the resistance of the civil service, which are afraid to lose rent-seeking opportunities. This being said, initiating a dialogue around the value of reform is an important step on the way to building the political will needed to overcome these obstacles.

6 Judiciary and Land Dispossession Litigation

In Bangladesh, as in most developing countries, landlessness is often synonymous with poverty, and often extreme poverty. Landlessness has greatly increased in Bangladesh, with the proportion of landless rural workers or pure tenants surging from 45% to 65% since 2000 (Sen, Reference Sen2018). Moreover, a survey conducted by the MJF (2015) found that around 70% of households reported losses of land in the last 10 years, with 17% reportedly the victims of land grabbing. How such practices can be curbed and how they can be dealt with in the judicial sector are crucial questions.

The chapter by Ferdousi, Islam, and Raihan provides a narrative analysis of the process through which involuntary land dispossession takes place in the socio-economic context of Bangladesh, and the relative inability of the judiciary to resolve such cases. It also provides information about the way the judiciary works in general – another aspect of ‘state capacity’ where Bangladesh appears relatively weak, for both logistical and institutional reasons. Logistical reasons relate to a lack of resources, whereas institutional reasons relate to the way the judiciary is influenced by both political and economic interests, as well as the fact that most actors in the judiciary extract rents from the system and act, almost collusively, to maintain its dysfunctionality.

Despite a constitutional mandate for the separation of the judiciary from the executive organs of the state, the judiciary still remains somewhat vulnerable to political manoeuvring and vested interests. As noted by Jean-Philippe Platteau in his comments, this is already true at the highest level of the system, as supreme court judges are nominated by the Ministry of Law, Justice and Parliamentary Affairs, thus making them vulnerable to political strategies. A 1999 Supreme Court ruling that the Government must strictly implement separation of the judiciary and the executive was never fully executed. Political interference is also observed at the local level in instances of land dispossession. In several cases reported in this chapter, the final judgement is directly influenced by political pressure. It may also sometimes happen that political pressure aims at indefinitely postponing a final judgement.

A second general weakness of the judiciary is the increasing backlog of unresolved cases, due mainly to a lack of capacity and resources. In Bangladesh, civil cases still follow century-old procedures which legally require manual recording at each stage of the proceeding of a case. This consumes considerable amounts of time and the dependence on manual paperwork contributes to an increasing backlog. Delays are compounded by the fact that records of previous stages are often lost from the registers, which further impedes cases. Other factors responsible for the slow processing of cases are the shortage of judges, poor investigation by the police, an excessive number of adjournments, an absence of witnesses, a lack of capacity of legal professionals, and failures in coordination among different administrative departments. A lack of authority to compel clerks, advocates, litigants, or witnesses to comply with the due codes, rules, and processes is another source of delay. Institutional failures in other administrative areas matter too, especially in land management, as attested by the frequent difficulty of obtaining appropriate records of land operations.

Another major cause of delay is the collusion between employees in land administrative bodies, the judiciary, and law enforcement agencies, as well as between numerous actors, including lawyers and clerks, which often has the effect of delaying case resolution through multiplication of the procedures. A simple land dispossession litigation generates a comparatively small amount of rent through the bribes to be paid by the plaintiff or the defendants to clerks, advocates, and judges, but the rent increases significantly if the whole process can be slowed down, and the opportunities to extract a bribe are multiplied, allegedly for the purpose of ‘accelerating’ the resolution of the case. A suspicion then arises among the actors involved in a case that collusion exists that aims to delay its conclusion. The higher the number of interactions between different parties, the higher the amount of transaction cost and rents that can be extracted.

Ultimately, overcoming institutional inefficiencies in the judiciary of Bangladesh will require a lot more than the usual generic reform agendas. While there is a clear need for capacity building within the judiciary, other urgent steps include a thorough review and proper amendments of the existing laws in order to update century-long administrative practices and to establish low-cost legal services for the poor and underprivileged. Most importantly, the Government must strive to ensure a separation of powers between its executive and judicial branches, to uphold judicial independence at the central as well as at the local levels. But ensuring judicial independence alone may not be sufficient for proper enforcement of the rule of law. Forces that have an interest in the status quo will fiercely oppose any reform in that direction, including the actors who benefit from the low capacity of the judiciary system in charge of land litigation. External interventions are required to break the collusion among actors in land dispossession litigation cases, knowing that they will oppose a reform that would threaten their way of generating rents.

III The Institutional Diagnostic

Based on the material accumulated so far, the institutional diagnostic presented in this section is organised into the following three parts. First, looking across the summaries of the preceding chapters, a list of three basic institutional weaknesses is highlighted. These are common to all or several of the areas covered above and are also consistent with the analysis of institutional challenges based on cross-country indicators, and those based on the responses provided by a number of decision makers in Bangladesh to the CIS. Second, this list is then broadened in a so-called Diagnostic Table where the basic institutional weaknesses appear with their economic and social consequences on one side and their proximate causes on the other, the latter being themselves related to several deep factors. The reason for this juxtaposition is that the identified weaknesses are often more the symptoms than they are the causes of an institutional problem. A diagnostic must therefore start from the symptoms in order to go to the root of the problems, and then to the possible remedies, which depend themselves on which deep factors are at play. Third, based on that comprehensive view of institutional challenges in Bangladesh, the three basic institutional weaknesses are re-examined in the light of their relationship with the rest of the diagnostic table, and with a view to considering potential reforms, and their political economy context. Some proximate causes are also subjected to the same reflection due to their particular role in affecting the basic weaknesses, and the reforms they call for.

It is important to note that this diagnostic was originally conceived before the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, and that it has, therefore, been necessary to reassess the argument in the light of subsequent events. The conclusion of that reassessment, however, is that the essential findings and structure of the diagnostic are unchanged. Indeed, they are strengthened by an analysis of Bangladesh’s experience of COVID-19. Not only are the three basic institutional weaknesses and their proximate causes as pertinent as ever in terms of general economic development, but in fact provide a useful means of understanding why the pandemic affected Bangladesh in the way that it has, thus far, and in anticipating the likely future challenges that the country now faces as a result. The rationale for reform remains unchanged as a consequence, but the COVID-19 crisis calls for some specific recommendations that we make explicit.

A Three Overall Basic Institutional Weaknesses of Bangladesh’s Development

The general feeling that results from the short summaries of the previous chapters (see Section II.E) is that of a dichotomy in the recent economic history of Bangladesh between remarkable growth achievements very much centred on RMG exports, on the one hand, and deep weaknesses in most other sectors, on the other. These deep weaknesses make the country comparable to many low-income countries that have growth and development performances far below Bangladesh’s. It is as though Bangladesh’s growth achievement has created few incentives, and possibly even generated disincentives, for the ruling elites to address major sources of inefficiency and inequity that coexist with growth factors. The consequences of this neglect, in terms of the poor functioning of the state, the poor delivery of public goods, the high degree of corruption, and rising income inequality, were and still are politically manageable as long as the growth engines continue to raise living standards and reduce poverty. On the other hand, institutional failures may become a prime obstacle to further development if the slowdown that is presently observed in RMG exports and remittances increases. Unfortunately, there are many reasons to believe that this possibility may materialise, especially so in the present conditions of a global economic crisis caused by the COVID-19 crisis. This makes it all the more urgent to remedy the institutional weaknesses that presently prevent the economy of Bangladesh from achieving better performance and that might hamper necessary adjustments in the future.

The many problems mentioned earlier may be grouped into three overall ‘basic institutional weaknesses’:

Supremacy of ‘deals’ over formal industrial (or development) policymaking

By this it is meant that industrial – or, more generally, development – policies and key investment or resource allocation decisions often result from agreements, that is ‘deals’, made between the political elite in government and the economic elite. These deals concern particular operations or programmes that are chosen on an ad hoc basis, meaning without reference to some well-defined overall strategy. Deals relating to RMG exports yielded positive results. Others did not, or prevented better options, like export diversification, being taken. To be sure, deals are not necessarily incompatible with formal industrial policies as long as they fit a well-defined general strategy and the state keeps full control of the support provided to particular industries. It is not clear, however, that the deals environment observed in Bangladesh meets these requirements.

Ineffective regulation

This refers to the difficulty the Government faces in regulating certain key activities in order to ensure greater efficiency and equity in the economy. In some cases what is at stake is the legal framework for such regulation, which may be outdated or otherwise unfit for the objective pursued, and in relation to which reform attempts have consistently failed. In other cases, the framework may be in place but there is not sufficient capacity to implement it. Examples in the areas covered in this volume include the dysfunction of the banking system, the failure to regulate labour conditions in a key sector like RMG, or simply the dismal performance of taxation. Regulatory agencies in other areas that are not covered in this volume may be equally ineffective.

Weak state capacity

This major governance failure in Bangladesh takes different forms. Some are readily apparent, such as the lack of public resources and therefore the limited provision and low quality of public goods, the lack of skills in public service, delays or high costs incurred in the provision of infrastructure, or an inefficient administrative organisation. Others are more obscure, such as the high level of corruption in most administrative clusters, which tends to make the delivery of public services both inefficient and inequitable, reduces revenues, and often discourages economic initiatives. Weak capacity is particularly patent in the judiciary. A lack of resources and a high level of corruption make the judiciary completely ineffective in major areas, especially in the protection of property rights in agriculture.

To be sure, these three ‘basic institutional weaknesses’ are not independent of each other. The ineffectiveness of regulation or the inability to integrate deals with the business elite within a consistent development framework may be considered as constituting weak state capacity. Deals themselves may be viewed as the consequence of a limited state capacity, that is the lack of a coherent and comprehensive perspective on development, or ineffective regulation. Yet these three headings appear as a convenient grouping of the many deficiencies pointed to in the chapters in this volume. At the same time, they cover different aspects of the malfunctioning of the country’s institutions.

It is reassuring that these three basic institutional weaknesses conform well with the general institutional weaknesses revealed by global institutional indicators. It certainly comes as no surprise that global indices have ranked Bangladesh in the lower part of the scale on indicators like ‘rule of law’ or ‘bureaucratic quality’. The basic weaknesses also match the opinions expressed by the respondents to our questionnaire survey, and by the key informants whom we interviewed. In this respect, the emphasis put by our interviewees on the role of informal arrangements, that is ‘deals’, is worth singling out. Nonetheless, the present institutional diagnostic will go much further than these mechanical diagnostic tools in providing a deeper understanding of the basic weaknesses of the institutional fabric of the country and of the way they interact to impinge on the pace and structural features of national development.

A priori, many aspects of the three basic weaknesses could be corrected by simple reforms. Auditing government policies and evaluating civil servants, enforcing penalties for corruption, changing the rules for appointing the governor of the Central Bank, digitalising land records or judiciary decisions, etc. are all reforms that are rather evident and could drastically improve the institutional environment in Bangladesh and enhance its development. Yet, for these reforms to be enacted, and successfully implemented, other conditions must be met that most often involve political economy mechanisms or more fundamental constraints on the society and the economy. The three basic weaknesses set out above result from ‘proximate causes’ that need to be identified, and which are themselves linked to ‘deep factors’ that are rooted in the way the political system and the civil society work, in conjunction with other possible exogenous factors. It is this complex relationship that will now be explored.

B The Diagnostic Table

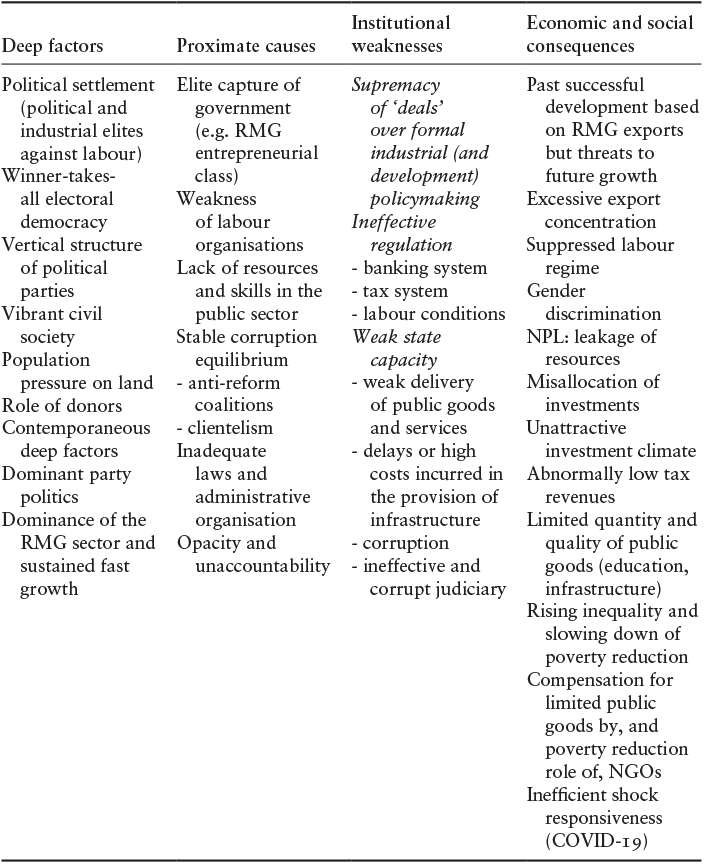

Table 10.1 offers a general view of the institutional diagnostic that the in-depth analysis in this volume leads to. Starting from the three basic institutional weaknesses defined in Section III.A, the table can be read from left to right, with the right-hand column showing the major economic and social consequences of these weaknesses. It can also be read from right to left, with a column showing the main proximate causes of the weaknesses and then a column displaying the deep factors that ultimately determine the feasibility of reforms that could correct the proximate causes and improving the institutional context. While reading this table, it is important to notice that logical implications go from column to column, not from one item in a column to the item in the same row in another column. In other words, it is generally the case that all items in a column depend on, or jointly determine, the items in another column. It should also be kept in mind that the relationships between the items in different columns, and within a column, may be circular. For instance, one may hold the view that it is the success of the RMG export sector that has made governments less attentive to regulatory issues, which in turn explains the dysfunction of the banking sector and a sub-optimal allocation of funds away from non-RMG potential export sectors.

Table 10.1 The institutional diagnostic table

| Deep factors | Proximate causes | Institutional weaknesses | Economic and social consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Political settlement (political and industrial elites against labour) Winner-takes-all electoral democracy Vertical structure of political parties Vibrant civil society Population pressure on land Role of donors Contemporaneous deep factors Dominant party politics Dominance of the RMG sector and sustained fast growth | Elite capture of government (e.g. RMG entrepreneurial class) Weakness of labour organisations Lack of resources and skills in the public sector Stable corruption equilibrium - anti-reform coalitions - clientelism Inadequate laws and administrative organisation Opacity and unaccountability | Supremacy of ‘deals’ over formal industrial (and development) policymaking Ineffective regulation - banking system - tax system - labour conditions Weak state capacity - weak delivery of public goods and services - delays or high costs incurred in the provision of infrastructure - corruption - ineffective and corrupt judiciary | Past successful development based on RMG exports but threats to future growth Excessive export concentration Suppressed labour regime Gender discrimination NPL: leakage of resources Misallocation of investments Unattractive investment climate Abnormally low tax revenues Limited quantity and quality of public goods (education, infrastructure) Rising inequality and slowing down of poverty reduction Compensation for limited public goods by, and poverty reduction role of, NGOs Inefficient shock responsiveness (COVID-19) |

There is no need to elaborate on the right-hand column of the table, which is only a reminder of the major economic and social implications of the institutional weaknesses discussed in the preceding section. What is new in the table are the first two columns.

1 Proximate Causes for Institutional Weaknesses

Six items appear in the ‘proximate causes’ column. They are briefly discussed here, while emphasising how they relate to the basic weakness column.

The ‘elite capture of the Government’ is particularly important for the supremacy of deals over formal industrial policy, and, specifically, the role played by the business class of the RMG manufacturing sector. As the sector gained in importance, both through its size in the domestic economy and its dominant role in exports and general economic growth, it quickly acquired considerable leverage over the Government, whichever party was in power at the time. Even the regulation of the sector, which would normally be expected to fall under the responsibility of some entity within the Ministry of Industry, is completely internalised within the sector. Its producer unions, one for woven wear and another for knitwear, are thus able to impose industrial policy choices in their own favour, often at the expense of other export manufacturing sectors, and, possibly, future growth.

The ‘weakness of labour organisations’ in Bangladesh results from a political settlement between political and industrial elites at the expense of labour (one of the ‘deep factors’). Labour union leaders are generally affiliated to political parties whose leaders have strong links with private firms, especially in the RMG sector. As a result, unions are generally disinclined to challenge employers, which may be the reason why over the last 30 years wages lagged GDP per capita by a wide margin and income inequality increased. The weakness of labour unions and low wages are key factors in the global competitiveness of the RMG sector, but, paradoxically, they may also be responsible for the structural inertia of Bangladesh’s industrial sector, including within RMG. Faster growing wages would have been an incentive to move towards higher value-added and more ‘complex’ products, along the line of the Hidalgo et al. (Reference Hidalgo, Klinger, Barabàsi and Hausmann2007) theory of industrial development.Footnote 15

The ‘lack of resources and skills’ within the public sector is a constraining factor that is common to most developing countries. In the case of Bangladesh, however, it is not only an issue of a low level of income but also of a particularly low level of public revenue – and particularly tax revenue. It is a cause of institutional weakness, but also a consequence, since it results largely from a dysfunctional tax authority. This is an example of a circular relationship between the elements of the diagnostic table (Table 10.1).

The existence of a ‘stable corruption equilibrium’, or a culture of corruption, explains why it is so difficult to control corruption, at least directly though carrots and/or sticks. When every actor expects others to behave in a corrupt way, no incentive exists to deviate from that common behaviour, and even carrot-and-stick approaches may become ineffective. Moving out of that equilibrium requires both a strong political will and the effective use of power.Footnote 16

The presence of ‘inadequate laws and administrative organisations’ in Bangladesh is a rather direct cause of why some institutions do not function well. It also means that effective reforms of these institutions require the modification of the legal or administrative framework. Examples mentioned earlier include some land laws inherited from the colonial or the pre-independence period, or overlapping administrative responsibilities in land matters, primary education, or the regulation of banking.