9.1 Introduction

In this article, prepared for a special JCLE symposium, I revisit my initial findings regarding the prevalence of ‘horizontal directors’ in the United States.Footnote 1 ‘Horizontal directors’ serve on the board of multiple companies operating within the same industry. I have previously spotlighted the prevalence of horizontal directors in the US, despite a prima facie prohibition on director service among competitors.

Despite that spotlight and increasing attention to common ownership and to director interlocks, this Article explores six additional data years to further demonstrate the prevalence of horizontal directors as recently as the end of 2019.

In fact, in this project, the original dataset has been enhanced with bookend data from 2007 to 2009 and 2017 to 2019 for the director-level analysis. These expanded data confirm the rise of horizontal directors previously discussed and highlight their continued prevalence even against a backdrop of increased attention to the effects of common ownership and directors’ interlocks.

Horizontal directors are significant because they stand at a unique intersection of antitrust law and corporate governance. They offer many legitimate governance and operational benefits to companies and shareholders but at the same time pose significant concerns both to the governance of the corporation and to antitrust policy. Despite that significance, horizontal directors have yet to receive the proper attention from regulators, stock exchanges, and investors.

This lack of attention to the horizontal aspect of director interlocks is particularly surprising for two reasons. First, existing US antitrust regulation specifically prohibits directors from serving on the boards of two competitors,Footnote 2 so sharing a director across companies in the same industry may violate these laws. Second, antitrust law has re-emerged in recent yearsFootnote 3 commanding increased attention to market concentration and consumer welfare (specifically in merger decisionsFootnote 4 and ‘horizontal shareholding’Footnote 5 by institutional investors). This emerging literature has sparked a vivid academic and public debate regarding the effects of shareholder concentration on antitrust policy.Footnote 6 Specifically, scholars have raised concerns regarding the incentives of companies to compete where major institutional shareholders hold large equity positions in all competitors. While market concentration by large investors has been widely acknowledged, a vivid debate has ensued on whether such concentration materialises in ways that promote anticompetitive behaviour.Footnote 7 As a by-product of this debate, recent focus has been directed to the question of which channels common owners use to effect anticompetitive behaviour.

For instance, one channel prominently discussed in recent years is executive compensation. Some suggest that common owners may either actively discourage performance-sensitive compensation or not actively push for a particular compensation plan and instead promote the status quo which lets executives ‘get away with high performance-insensitive pay’.Footnote 8 While less plausible, another channel is through a targeted strategy of specific actions that is communicated to management that promotes portfolio value even at the expense of firm value.Footnote 9 In this channel, a common owner obtains leverage over management with its voting power and its ability to sell shares and decrease the market price of firm stock in order to promote its strategy.Footnote 10 Interestingly, and surprisingly, the role of directors as potential conduits of common ownership has been left underexplored. Specifically, horizontal directors might create this exact channel for common owners’ influence, therefore facilitating anticompetitive effects on the market.Footnote 11 Alternately, horizontal directors may alone serve as the channel through which anticompetitive practices are achieved, without the need to pin such results on common owners.Footnote 12

Equally important, horizontal directors are not a rarity: in fact, as shown below, empirical data reveal hundreds of directors concurrently serving on boards of companies operating in the same or similar industries. More so, the prevalence of horizontal directors is on the rise. Yet, despite the rise in horizontal directorships over time, proactive corporate disclosure of horizontal directors remains sparse.Footnote 13 Notably, the presence of horizontal directors across industry lines is not equal. Some industries are more prone to having horizontal directors than others. For example, while the construction industry has on average 10.6% industry-level horizontal directors serving on two or more companies’ boards, the manufacturing industry has 33.7%.Footnote 14 This variance across industries invites for further research trying to connect industry levels of anticompetitiveness and horizontal directorships.

This Article proceeds as follows. Part II starts by providing an overview of the unique case of horizontal directors. Part III then provides a refreshed empirical analysis of the S&P 1500 director dataset and also revisits the company-level analysis of disclosure practices. Part IV then provides an overview of the current US legal framework governing and regulating horizontal directors. Part V discusses and analyses the implications of those results in more detail in light of the potential benefits and concerns horizontal directors may bring.

9.2 From Interlocks to Horizontalness

Directors’ service on multiple boards has drawn both investor and academic attention,Footnote 15 mostly focusing on one of two areas: (1) the number of board seats a director holds and whether directors who hold several board positions have an impact on company performance or other governance metricsFootnote 16 or (2) the ‘interlocks’, or the connections and bridges, created between two (or more) companies by having a director that serves on both (or multiple) boards.Footnote 17

Busy directors, and the interlocks they create, are a natural and inevitable by-product of a corporate culture that taps directors to serve on multiple boards at once.Footnote 18 The benefits of serving on multiple boards are tangible. Busy directors have more experience, provide more connections and develop more industry expertise at a rate that exponentially increases with the number of boards they serve.Footnote 19 Conversely, less-busy directors provide fewer tangential benefits derived from busyness to firms.Footnote 20

While there is no shortage in attention to busy directors,Footnote 21 missing from current discourse is a more nuanced account of the boards on which busy directors serve. While by definition directors serving on more than one board fall into the definition of a ‘busy director’, some of these busy directors also serve on more than one board in the same industry – these are what I termed as horizontal directors.Footnote 22

Horizontal directors are particularly important because their prevalence, as discussed below, raises both governance and antitrust concerns. Horizontal directors raise antitrust concerns since their concurrent board seats provide a channel between companies in the same industry. These channels can lead to either collaboration and/or collusion.Footnote 23 Additionally, horizontal directors also raise corporate governance concerns, such as reduced independence and increased conformity in governance practices that could lead to systemic governance risk.Footnote 24 Moreover, the rise in horizontal directors comes against a backdrop of heightened concentration in the US markets. More than 75% of US industries experienced a rise in concentration levelsFootnote 25 in recent years.Footnote 26 As the distribution of a given market among participating companies becomes less spread out, the anticompetitive effects of collusion and price-fixing intensify. Therefore, the potential impact of horizontal directors is also amplified.

A final factor contributing to the profound effect horizontal directors can have in the corporate landscape is a product of the fact that demarcation lines among industries are becoming increasingly more difficult to ascertain.Footnote 27 Because horizontal directors are identified based on industry, the murkier industry lines become, the harder it will be to identify and monitor horizontal directors for anticompetitive behaviour.

9.3 Revisiting Horizontal Directors: Empirical Findings

This Part provides augmented data on the prevalence of horizontal directors in the US as well as information disclosed to investors on horizontal directors. The data presented herein extend prior analysis,Footnote 28 expanding the analysis to include data from 2007 to 2009 and 2017 to 2019, therefore providing an even more broad view of the rise of director horizontalness and the persistence of it even as recently as January 2020.

9.3.1 Horizontal Directors in S&P 1500 Companies

9.3.1.1 Methodology

This Part examines the prevalence of horizontal directors on boards in the same industry for companies within the S&P 1500 from 2007 and through 2019. The data for this sample were originally compiled from Equilar’s BoardEdge dataset.Footnote 29 Both director-level data and company-level data were obtained for each company within the S&P 1500 for each year previously mentioned. These separate datasets were merged to create one panel dataset at the director-company-year level where each individual case describes a director’s service on a specific S&P 1500 board as well as any additional boards that specific director served on and that were outside of the S&P 1500. For the purposes of analysis all directors were included, whether they were designated as independent or not. This consolidated dataset was subsequently supplemented with company-level data from FactSet and the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) Association to add NAICS codesFootnote 30 and industry classifications for groups of SIC and NAICS codes.

Directors were coded as ‘horizontal’ using four classifications: whether a director served on more than one board in the same (1) SIC code, (2) SIC industry, (3) NAICS code, or (4) NAICS industry. Because an ‘industry’ contains multiple SIC codes or NAICS codes, the industry-horizontal classifications are a broader measure than the classifications based on specific SIC or NAICS codes. However, using both SIC and NAIC classifications allows for a more robust analysis. Directors were given a binary variable (0 or 1) for each classification indicating their horizontal status. These variables were used to calculate the number of horizontal boards on which the director served in a given year. Directors were also coded as ‘busy’ – serving on more than one board at a time – regardless of whether those boards are horizontal. Each busy director was individually coded with an indicator variable as well as a count of the number of boards on which they served each year.

9.3.1.2 Director-Level Analysis

As depicted in Table 9.1, the expanded data show the number and percentage of directors in the S&P 1500 who served on more than one board. From 2007 to 2019, more than 30% of all directors sat on more than one board, and a substantial number of directors (around 12%) held three or four board positions. The data covering the 2010–2016 years (‘The Original Data’) pointed out that the percent of busy directors did not vary more than 2% from 2010 to 2016. However, the supplemented data from 2007 to 2009 and 2017 to 2019 show a more prominent incline in busy directors over time. For example, the number of directors that served on two boards increased by 17% from 2007 to 2019, and the number of directors that served on three boards increased by 39% for this same time period.

Table 9.1 Number of boards a director sits on

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7+ | N | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

2019 | 61.93% | 24.99% | 9.21% | 3.11% | 0.63% | 0.09% | 0.04% | 100.00% |

6,159 | 2,485 | 916 | 309 | 63 | 9 | 4 | 9,945 | |

2018 | 60.81% | 24.91% | 10.14% | 3.22% | 0.75% | 0.12% | 0.05% | 100.00% |

6,175 | 2,530 | 1,030 | 327 | 76 | 12 | 5 | 10.155 | |

2017 | 60.42% | 25.08% | 10.43% | 3.16% | 0.78% | 0.09% | 0.03% | 100.00% |

5,943 | 2,467 | 1,026 | 311 | 77 | 9 | 3 | 9,836 | |

2016 | 65.14% | 22.44% | 9.08% | 2.66% | 0.52% | 0.10% | 0.04% | 100.00% |

8,191 | 2,822 | 1,142 | 335 | 66 | 13 | 5 | 12,574 | |

2015 | 63.75% | 23.49% | 9.05% | 2.92% | 0.59% | 0.13% | 0.07% | 100.00% |

7,937 | 2,925 | 1,127 | 363 | 74 | 16 | 9 | 12,451 | |

2014 | 63.55% | 23.37% | 9.22% | 2.83% | 0.79% | 0.18% | 0.07% | 100.00% |

7,960 | 2,927 | 1,155 | 354 | 99 | 22 | 9 | 12,526 | |

2013 | 63.31% | 23.28% | 9.78% | 2.70% | 0.70% | 0.17% | 0.07% | 100.00% |

7,822 | 2,877 | 1,208 | 333 | 86 | 21 | 9 | 12,356 | |

2012 | 63.92% | 23.24% | 9.40% | 2.44% | 0.78% | 0.14% | 0.07% | 100.00% |

7,755 | 2,820 | 1,141 | 296 | 95 | 17 | 8 | 12,132 | |

2011 | 64.23% | 23.25% | 9.11% | 2.44% | 0.75% | 0.19% | 0.03% | 100.00% |

7,650 | 2,769 | 1,085 | 291 | 89 | 23 | 3 | 11,910 | |

2010 | 63.63% | 23.41% | 9.20% | 2.68% | 0.74% | 0.30% | 0.03% | 100.00% |

7,564 | 27,83 | 1,094 | 318 | 88 | 36 | 4 | 11,887 | |

2009 | 72.88% | 18.76% | 6.03% | 1.71% | 0.50% | 0.12% | 0.01% | 100.00% |

10,090 | 2,597 | 835 | 237 | 69 | 16 | 1 | 13,845 | |

2008 | 71.60% | 19.88% | 6.35% | 1.56% | 0.49% | 0.11% | 0.02% | 100.00% |

10,164 | 2,822 | 902 | 221 | 69 | 15 | 3 | 14,196 | |

2007 | 69.60% | 21.35% | 6.64% | 1.80% | 0.47% | 0.11% | 0.02% | 100.00% |

9,675 | 2,968 | 923 | 250 | 66 | 15 | 3 | 13,899 |

Additionally, the percent of directors that serve on two or more boards has increased despite the fact that the total number of directors in the sample has decreased by 3% on average each year (total decline of 28% from 2007 to 2019).

As I have previously underscored, horizontal directors are not outliers among directors of public companies – the opposite is true. Table 9.2 shows that the trends previously highlighted with respect to the Original Data are amplified by the additional years included. Although the data show that the percent of busy directors that share an industry within their boards served does not vary more than 8% in this 13-year period, a closer look at the data shows more nuanced patterns. For example, the number of directors that served on boards of at least two companies within the same industry slowly increased from 2007 to 2009. However, from 2009 to 2010 there was a 20% decrease in the number of directors that served on two or more boards within the same industry, showing some year-to-year volatility in the appointment of horizontal directors.

Table 9.2 Number and percentage of busy directors sharing an industry within boards served

# of boards | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

2 | 895 (34%) | 994 (35%) | 1473 (46%) | 952 (34%) | 1002 (36%) | 1056 (37%) | 1077 (37%) | 1094 (37%) | 1075 (37%) | 1051 (37%) | 936 (38%) | 960 (38%) | 954 (38%) |

3 | 519 (62%) | 571 (63%) | 618 (65%) | 676 (62%) | 687 (63%) | 724 (63%) | 800 (66%) | 769 (67%) | 751 (67%) | 767 (67%) | 675 (65%) | 674 (65%) | 596 (65%) |

4 | 197 (79%) | 184 (78%) | 266 (83%) | 258 (81%) | 237 (81%) | 237 (81%) | 267 (80%) | 289 (82%) | 300 (83%) | 282 (84%) | 262 (84%) | 281 (85%) | 269 (86%) |

5 | 63 (90%) | 62 (90%) | 97 (92%) | 80 (91%) | 81 (91%) | 89 (94%) | 79 (92%) | 93 (94%) | 67 (91%) | 62 (94%) | 75 (95%) | 73 (95%) | 56 (90%) |

6 | 16 (100%) | 15 (100%) | 25 (93%) | 33 (92%) | 22 (96%) | 16 (94%) | 21 (100%) | 22 (100%) | 16 (100%) | 13 (100%) | 9 (100%) | 12 (100%) | 10 (100%) |

7+ | 1 (100%) | 4 (100%) | 10 (100%) | 4 (100%) | 3 (100%) | 8 (100%) | 9 (100%) | 9 (100%) | 9 (100%) | 5 (100%) | 2 (67%) | 4 (80%) | 3 (75%) |

Although industry classification is broader than a single SIC or NAICS classification, combining multiple codes, the number of horizontal directors is substantial under both metrics. There were 1,888 directors that served on the board of more than one company within the same industry in 2019. On a more granular level, there were 412 directors (10.8% of directors serving on more than one board) who served on at least two companies in the same industry per four-digit SIC code. Similarly, there were 250 directors (9.2% of the directors serving on more than one board) that served on at least two companies’ boards within the same NAICS code.

The number of directors that serve on more than one company with the same NAICS or SIC code has decreased by only 3% from 2016 to 2019 (Table 9.3). Therefore, there has not been a significant change in the striking presence of horizontal directors since the Original Data.

Table 9.3 Number and percentage of busy directors sharing SIC/NAICS within boards served

# of boards | SIC/NAICS | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

2 | SIC | 140 (5%) | 149 (5%) | 180 (6%) | 183 (6%) | 195 (7%) | 208 (8%) | 209 (8%) | 170 (7%) | 169 (7%) | 184 (7%) |

NAICS | 104 (4%) | 120 (4%) | 144 (5%) | 155 (5%) | 165 (6%) | 159 (5%) | 147 (5%) | 143 (6%) | 151 (6%) | 156 (6%) | |

3 | SIC | 101 (9%) | 103 (9%) | 123 (11%) | 139 (12%) | 129 (11%) | 148 (13%) | 150 (13%) | 146 (14%) | 154 (15%) | 129 (14%) |

NAICS | 80 (7%) | 81 (7%) | 99 (9%) | 118 (10%) | 115 (10%) | 129 (11%) | 132 (12%) | 121 (12%) | 123 (12%) | 107 (12%) | |

4 | SIC | 45 (14%) | 43 (15%) | 53 (18%) | 70 (21%) | 68 (19%) | 85 (25%) | 102 (29%) | 73 (23%) | 77 (23%) | 67 (21%) |

NAICS | 36 (11%) | 40 (14%) | 41 (14%) | 57 (17%) | 65 (18%) | 62 (17%) | 56 (17%) | 65 (21%) | 65 (20%) | 63 (20%) | |

5 | SIC | 21 (24%) | 19 (21%) | 28 (29%) | 28 (33%) | 31 (31%) | 24 (32%) | 26 (39%) | 38 (48%) | 29 (38%) | 22 (35%) |

NAICS | 14 (16%) | 14 (16%) | 28 (29%) | 23 (27%) | 23 (23%) | 19 (26%) | 24 (36%) | 35 (44%) | 23 (30%) | 14 (23%) | |

6 | SIC | 13 (36%) | 8 (35%) | 9 (53%) | 8 (38%) | 13 (59%) | 9 (56%) | 10 (77%) | 7 (78%) | 7 (58%) | 9 (90%) |

NAICS | 13 (36%) | 10 (43%) | 7 (41%) | 5 (24%) | 11 (50%) | 7 (44%) | 8 (62%) | 5 (56%) | 6 (50%) | 9 (90%) | |

7+ | SIC | 1 (25%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (62%) | 7 (78%) | 6 (67%) | 4 (44%) | 2 (40%) | 2 67%) | 3 (60%) | 1 (25%) |

NAICS | 1 (25%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (62%) | 6 (67%) | 5 (56%) | 3 (33%) | 2 (40%) | 2 (67%) | 3 (60%) | 1 (25%) | |

Total | SIC | 321 (7.4%) | 322 (7.5%) | 398 (9.2%) | 435 (9.5%) | 442 (9.7%) | 478 (10.5%) | 499 (11.3%) | 436 (11.1%) | 449 (11.2%) | 412 (10.8%) |

NAICS | 248 (5.7%) | 265 (6.2%) | 324 (7.5%) | 364 (8%) | 384 (8.4%) | 379 (8.3%) | 369 (8.4%) | 371 (9.5%) | 371 (9.2%) | 350 (9.2%) |

Table 9.4 further shows that the percentage of horizontal directors as a percent of busy and total directors has been trending upwards over time with a merely a slight decline seen in the last two years. For example, in 2010, 7.4% of all horizontal directors sat on at least two boards of within the same SIC classification. This number increased by 7% on average each year from 2010 to 2016 but decreased by 2% in both 2018 and 2019. A similar trend was observed under the NAICS classification with an average increase in that metric of 8% each year with a decline of 3% in the last two years.

Table 9.4 Time trend of horizontal directors

Year | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

% of Industry-Horizontal Directors out of All Directors | 16.9 | 17.1 | 17.6 | 18.2 | 18.2 | 17.8 | 17.3 | 19.7 | 19.5 | 18.8 |

% of Industry-Horizontal Directors out of Busy Directors | 46.3 | 47.7 | 48.7 | 49.7 | 49.8 | 49.1 | 49.7 | 50.2 | 50.2 | 49.6 |

% of SIC-Horizontal Directors out of All Directors | 2.7 | 2.7 | 3.3 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.8 | 3.9 | 4.4 | 4.3 | 4.2 |

% of SIC-Horizontal Directors out of Busy Directors | 7.4 | 7.6 | 9.1 | 9.6 | 9.7 | 10.6 | 10.9 | 11.2 | 11 | 10.8 |

% of NAICS-Horizontal Directors out of All Directors | 2.1 | 2.2 | 2.7 | 2.9 | 3.1 | 3 | 2.9 | 3.7 | 3.6 | 3.6 |

% of NAICS-Horizontal Directors out of Busy Directors | 5.7 | 6.2 | 7.4 | 8 | 8.4 | 8.4 | 8.4 | 9.5 | 9.3 | 9.2 |

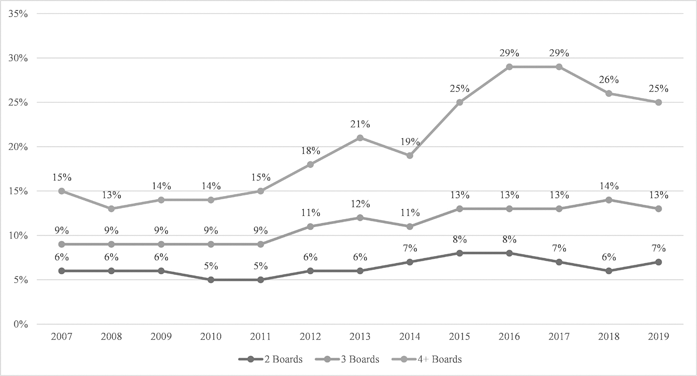

The pattern of steady growth followed by a slight decline is magnified in Figure 9.1. As depicted below, there has been a significant amount of growth from 2007 to 2016, particularly among directors serving on three or more boards. However, the expanded data show that the number of busy directors who sit on boards for companies within the same SIC code has slightly decreased in the last couple of years especially for directors serving on four or more boards, though it is still at significantly higher levels compared to 2010.

Figure 9.1 Percentage of busy directors sitting on at least two boards with the same SIC code

9.3.2 Disclosure Practices

The SEC imposes disclosure requirements on publicly traded companies in regard to their independent directors. Under Item 407 of Regulation S-K, companies are required to disclose which directors have been determined to be independent by the board of directors.Footnote 31 Companies must also disclose any non-independent members of the compensation, nominating, or audit committees.Footnote 32 And lastly, if any company has adopted its own director independence standards, in addition to the existing stock exchange rules, the company must disclose whether its own definition of ‘independence’ is available online.Footnote 33

Alongside the director independence disclosure requirements, companies are required to provide general information on their directors. Notably, Item 401(e)(2) requires companies to ‘[i]ndicate any other directorships held, including any other directorships held during the past five years, held by each director’.Footnote 34 Thus, Items 401 and 407 collectively require companies to disclose which directors are considered independent and to detail each director’s position on the board and any directorships held over the past five years.

The disclosure of board positions enables investors to better monitor and influence companies regarding board composition, including horizontal directors. However, companies vary in their disclosure practices and many lack several elements that would give shareholders access to information about horizontal directors.

To analyse the disclosure practices for companies within different market capitalisations, data were hand collected for fifty large-cap companies that make up the Fortune 50 and fifty small-cap companies that make up the Russell 2000. Data regarding the service of directors for other companies were collected from each company’s most recent form DEF 14A – an annual proxy filing required by the SEC.

Of the 100 companies surveyed, 99 had directors that served on another board. 97 of those companies disclosed this information, but only 24 of those companies provided a description of the other company or identified the company’s industry, as shown in Table 9.5. As previously noted, given the scarcity of information disclosed, it is very difficult to ascertain the presence of a horizontal director.

Table 9.5 Director disclosures

Level of proxy statement disclosure | Percent of companies |

|---|---|

Name of other boards served | 97 |

Industry of other boards served | 24 |

Current boards served | 95 |

Past boards served | 90 |

More than minimum disclosure of past five years | 53 |

Additionally, companies are only required to disclose a director’s prior roles for the last five years. Considering many companies (53%) only disclose the minimum required and some (6%) didn’t disclose any past information at all, this causes a great concern as the social and professional ties that a director develops while serving on other boards generally last for much longer than five years. Even when this information was disclosed, it is often buried within a paragraph and not presented in an easy-to-digest format that highlights this information. This leaves shareholders in the dark about the true prevalence of horizontal directors in their portfolio companies.

9.4 The Peculiar Presence of Horizontal Directors

9.4.1 The Regulatory Framework

Horizontal directorships are not completely unchecked, they are subject to several regulatory and market restrictions. While corporate and securities laws do not explicitly prohibit horizontal directorships,Footnote 35 a mosaic of regulatory and market-based restrictions does provide outer limits on their prevalence. Similarly, and more explicitly, antitrust laws attempt to target collusion between competitor companies with common directors.Footnote 36 Yet, these constraints may have not yielded the expected results. Indeed, despite the various constraints on horizontal directors, they remain prevalent.

9.4.1.1 Antitrust: Section 8 of the Clayton Act

The major aim of antitrust regulation is to promote healthy, fair, and robust competition among companies.Footnote 37 Horizontal directors may provide an avenue for companies to collude at the expense of consumers, in direct violation of antitrust regulatory goals.Footnote 38 Section 8 of the Clayton Act directly addresses this concern by prohibiting an individual or entity from serving on the board or as an officer of two competing corporations.Footnote 39 The crux of Section 8 revolves around the requirement that the two companies be competitors. Horizontal directors risk violating Section 8 if the two (or more) companies in question are considered ‘competitors’, as the Clayton Act requires.Footnote 40 Companies that produce the same products, companies that sell ‘reasonably interchangeable products within the same geographic area’,Footnote 41 and ‘companies that vie for the business of the same prospective purchasers, even if the products they offer, unless modified, are sufficiently dissimilar to preclude a single purchaser from having a choice of a suitable product from each’ all fall into the category of ‘competitors’ for purposes of Section 8.Footnote 42

The government can also target horizontal directors under Section 5 of the Federal Trade Commission Act (FTC Act) as an unfair practice or method of competition,Footnote 43 which provides the FTC with broader power to pursue per se violations and activities that violate the spirit of the Clayton Act.Footnote 44 It follows that horizontal directors do not have to overtly collude to violate antitrust law. The FTC recently demonstrated that anticompetitive effects outside of direct coordination could still violate antitrust principles, relying on evidence of unilateral effects.Footnote 45 Interestingly, horizontal directors are also prevalent in the EU.Footnote 46 However, unlike the US, horizontal directors in direct competitors are not prohibited in Europe, with the exception of Italy.Footnote 47 Italy prohibited interlocking in 2011 to promote competition in the banking, insurance, and financial sectors.Footnote 48

9.4.1.2 Fiduciary Duty Law

Directors are agents of the corporation, and therefore, they owe fiduciary duties to the corporation.Footnote 49 Because horizontal directors serving on the board of two companies owe concurrent fiduciary duties to each company, they are at a heightened risk of violating their fiduciary duties.Footnote 50

Delaware law has well-developed case law interpreting allegations of conflicting loyalties and corporate opportunity violations.Footnote 51 Loyalty conflicts typically arise in the parent–subsidiary setting. Delaware courts have declined to hold that dual-seated directors on parent–target subsidiary boards are per se conflicted,Footnote 52 but have found a violation of good faith and fair dealing and the ‘absence of any attempt to structure [the] transaction on an arm’s length basis’, and on that basis held that the directors were conflicted.Footnote 53

Additionally, under the corporate opportunity doctrine, directors may not take for themselves ‘a new business opportunity that belongs to the corporation, unless they first present it to the corporation and receive authorization to pursue it personally’.Footnote 54 Horizontal directors are more susceptible to potential corporate opportunity concerns due to their increased access to intra-company information.Footnote 55 The potential for these directors to, even unintentionally, violate their fiduciary duties is reason for them to limit their service on other boards, or at the very least restrict their exposure through corporate opportunity waivers,Footnote 56 recusals, and nondisclosure agreements.Footnote 57

9.4.1.3 Interlocking Director Committee Limitations

Horizontal directors are theoretically also restricted by The New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) and the NASDAQ Stock Market, both of which require that a majority of a company’s board of directors be independent.Footnote 58 Because director independence can depend on the director’s or her family members’ service in other companies, a horizontal director who serves on the board of multiple companies risks corroding her independence.Footnote 59

A specific restriction imposed by the NYSE that could impact the service of horizontal directors requires that simultaneous service on more than three public company audit committees be disclosed and approved by the board.Footnote 60 NASDAQ does not have the same rule, but in recent years there has been a marked drop-off in participation on more than three audit committees by directors.Footnote 61 As Table 9.6 demonstrates, the percentage of directors serving on the audit committees on four or more boards has declined dramatically, going from 8.33% in 2010 to 0.51% in 2019.

Table 9.6 Audit committee participation by busy directors

Audit participation | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

4+ Boards | 8.33% | 9.09% | 6.06% | 2.90% | 2.33% | 1.87% | 1.80% | 0.54% | 0.54% | 0.51% |

9.4.1.4 ISS/Glass Lewis

Institutional Shareholder Services, Inc. (ISS) and Glass Lewis wield influence in potentially comparable ways to that of governmental regulators by shaping corporate governance practices and corporate board policies.Footnote 62 Both ISS and Glass Lewis have adopted policies providing additional boundaries on the service of directors on multiple boards that companies will be expected to follow in order to win the support of ISS and Glass Lewis.

Because support of these proxy advisory firms is critical, their adopted policies likely increase the pressure on firms to reduce the number of busy directors, including horizontal directors. Even though their policies only serve as an outer limit on extreme cases of horizontal directorships and are unlikely to curb a large percentage of the cases, these standards still have an impact. As Part II demonstrated, the ratio of horizontal directors dramatically increases as they serve on more boards. Therefore, limiting – even modestly – the number of boards on which a director can hold a position has a stronger impact on those directors that have horizontal directorships.

9.4.1.5 Disclosure Rules

Finally, as discussed above, the SEC imposes disclosure requirements on publicly traded companies requiring them to provide general information on their directors, including information regarding their service on other boards. To the extent companies comply with such requirements, it may deter them from appointing horizontal directors if they anticipate regulatory pressure or investor push-back.

9.4.2 Horizontal Directors: Contrasting the Law with the Data

Antitrust laws prohibit horizontal directorships in competing corporations. Yet, as discussed herein, a significant number of directors serve on boards in the same industry, even if narrowly defined by NAICS and SIC classifications. While industry measures are only a crude proxy for the potential of two companies to compete, it is more likely that two companies operating in the same space will in fact compete. This is especially true given the wide definition of competition that has been applied to Section 8.Footnote 63 How can one explain this disparity of law and reality?

As I discussed in a prior writing, there are several key factors that help explain the prevalence of horizontal directors against this regulatory backdrop. First, it could be that companies sharing a director, even in the same industry, are not competitors, and therefore are not in violation of Section 8. However, this is unlikely given the fact that Section 8 applies to ‘companies that vie for the same purchasers’ even if dissimilar products.Footnote 64 Second, although Section 8 is a strict liability offense,Footnote 65 several practical and structural barriers hinder its enforcement. Historically, the FTC and DOJ have not brought Section 8 enforcements in court,Footnote 66 but instead have relied on self-policing and behind-the-scenes actions to pressure violators.Footnote 67 Additionally, private plaintiffs may be disincentivised from bringing a claim due to the lack of remuneration for individual shareholders, especially in cases where horizontal directors advance shareholder value. Furthermore, as discussed above, information regarding horizontal directors is not clearly disclosed or readily available to shareholders to identify these situations.Footnote 68

Section 8 also gives the FTC a lot of discretionary power and lacks clarity and a bright-line rule in applying the ‘competition’ requirement. This is further complicated by the fact that it is not always obvious to discern the market in which a company operates. The lack of a clear and public enforcement process adds a layer of difficulty in projecting FTC/DOJ enforcement and in deterring companies from violating Section 8 ex-ante.

9.5 Horizontal Directors: Zero-Sum Proposition?

Some level of collaboration between companies within the same industry can be beneficial to consumers; therefore, antitrust laws only target efforts that lead to anticompetitive outcomes or collusion.Footnote 69 Horizontal directors may provide value to the company and investors, such as contributing to the diffusion of beneficial corporate governance practices, networking, and expertise. By sitting on boards of multiple companies in the same industry, horizontal directors gain intimate knowledge can be a valuable asset to a director’s ability to advise and monitor the management team.Footnote 70 However, the presence of horizontal directors also presents concerns, such as an increased risk of antitrust collaboration, an increased risk of systemic governance risk,Footnote 71 and decreased director independence.Footnote 72 Furthermore, horizontal directors may facilitate anticompetitive practices that could further insulate management from market pressures which may lead to a loss of shareholder value in the long term.

As previously explored, this Article re-emphasises the need to shine a spotlight on horizontal directors and to address the accompanying concerns. Even though there has been a slight decline in the number of directors serving on companies within the same industry in the last few years, the overall prevalence of horizontal directors remains a concern.

Yet, horizontal directors are not necessarily a zero-sum proposition. Companies could still tap the valuable aspects of horizontal directors while at the same time minimising the concerns that they may present.

First, legislation that targets higher risk companies will be more effective at mitigating antitrust risks and will be easier to enforce uniformly, which will mitigate some of the current Section 8 underenforcement concerns. As I previously discussed,Footnote 73 some industries and SIC codes are more likely to have horizontal directors, and some of these horizontal-director-saturated industries also exhibit strong levels of industry concentration, perhaps making them a key starting point for evaluation.

Focusing the prohibition on concentrated industries might strike a desired balance. The right balance would allow companies to enjoy the benefits these directors provide while prohibiting their presence in cases where the costs to competition are more likely to outweigh these benefits. For instance, Section 8 could be revised to exempt from the prohibition industries with an HHI that is below a certain threshold. Aggressively enforcing Section 8 for that subset of public companies would reduce significant antitrust risk. Italy took a similar approach, in focusing on the banking sector. The main provision dealing with interlocking directors prohibits members of boards and any top manager of a company operating in the banking, insurance, and financial sectors from holding one of those offices in a competing company.Footnote 74 However, the Italian legislation was criticised for its inflexibility and lack of clarity.Footnote 75 For example, the Act did not include a de minimis exemption for very small firms that did not prompt the same concerns as larger companies.Footnote 76 If policymakers choose to amend the Clayton Act, they should take care to incorporate flexibility to strike the desired balance.

Second, regulators could consider an ex-ante design to Section 8 of the Clayton Act that would allow directors to apply for a waiver before accepting a horizontal directorship. By obtaining an ex-ante ‘no action’ waiver,Footnote 77 companies would be more certain about nominating potential directors. Furthermore, companies would be able to justify the nomination of directors that would technically violate the Act. Giving the FTC a veto right ex-ante would also reduce the need for costly ex-post enforcement and may lead to more consistent enforcement.

In fact, a similar arrangement is already employed in the context of interlocking bank directorships. The Federal Reserve’s (the Fed) Regulation L is similar to the Clayton Act in that it prohibits an officer or director of a bank from serving as an officer or director for more than one of any bank’s holding companies with over $10 billion in assets.Footnote 78 However, Regulation L allows the Fed to grant waivers when it determines that an interlock would not substantially lessen competition.Footnote 79 While the banking industry is more regulated than other industries, one can easily find ways to implement this rule in a cost effective way across other industries. For instance, the FTC may require a public notice to be filed, with a presumption of approval unless otherwise indicated within 20 days. The notice in turn will also allow shareholders, stock exchanges, and proxy advisors to apply private ordering restrictions if they so desire.

Third, and as previously mentioned, horizontal directors toe the line between antitrust and corporate governance, and a comprehensive reform should highlight the benefits of these directors as well as address the corporate governance risks. As Part II highlighted, many companies currently keep disclosures to the bare minimum required.Footnote 80 Thus, it is often difficult to even identify the industry of the other boards on which horizontal directors serve. Regardless of whether shareholders see horizontal directors as positively or negatively impacting the company, improved transparency via more comprehensive disclosures would enable shareholders to more effectively participate in corporate governance by making more informed director nominations and board recommendations.

An alternative approach to consider for reform would be updating stock exchanges’ self-regulation to better incorporate horizontal directorship concerns. One concern of horizontal directorships is the ability of directors to serve as independent directors when they have extensive experience in one industry. From a shareholder perspective, including directors with deep industry experience may add significant value to the company. Accordingly, stock exchanges may consider revising their independence definitions to exclude directors from being considered independent if they serve on the boards of two companies in the same SIC code, whether or not they are considered competitors. This restriction could strike a better balance between enabling companies from benefitting from horizontal directorship and preventing boards and directors from becoming too dependent on their specific industry connection.

Finally, state law and fiduciary law can also evolve to increase restrictions to mitigate the concerns that arise from the prominence of horizontal directors. Additionally, tightening judicial review of non-compete agreements, corporate opportunity waivers, and board fiduciary duties may position common law jurisprudence to more effectively address potential governance issues that stem from the presence of horizontal directors. For example, courts may examine corporate opportunity waivers more skeptically where a horizontal director is involved and where the opportunity is given to a horizontal company. The common law route can provide the flexibility and adaptability that regulatory intervention often lacks; however, it will depend on litigants voicing concerns.

9.6 Conclusion

In many ways, horizontal directors epitomise the push and pull of our corporate governance system. Directors are expected to monitor management, to provide expertise and networking, and to make the corporation’s most important decisions.Footnote 81 Yet, we lean on outsiders to serve as directors, and we allow, and even encourage, their service on other boards, potentially undermining their ability to appropriately serve their director role. Indeed, many directors serve on more than one board when given the opportunity. Director is a desired position due to the relatively limited time commitment to each board, significant salary and perks, and limited exposure to legal risk.Footnote 82 Additionally, serving on several boards across industries, within the same industry, and even within the same SIC code can benefit not only the director but also the companies she serves – at least under certain conditions.Footnote 83

Yet, there is an open question as to how horizontal directors should fit within our current antitrust regulatory framework and corporate governance regime. Moreover, how to appropriately balance the competing interests remains unresolved. Similarly, it remains unclear how we should view horizontal directorships given increased industry concentration and vivid discourse regarding horizontal mergers and horizontal shareholdings.

This Article demonstrates that horizontal directors remain a prevalent feature (and bug) of the US corporate landscape. Future research into horizontal directorships is still needed, given the increased reliance on the board as an institution,Footnote 84 and the emergence of contemporary antitrust discourse regarding horizontal ties between companies through common shareholders. Understanding that not all companies are created equal, investors may be better situated than regulators to account for the rise in horizontal directorships and offer market-based solutions to the inherent tension that these directors present.

10.1 Introduction

Interlocking directorates refer to situations in which one or more companies have one or more members of their boards in common. In the US, under Section 8 of the Clayton Act, competing companies are prohibited from having common board members.Footnote 1 In application of this prohibition, Eric Schmidt, CEO of Google, stepped down from the board of Apple in 2009. In the EU, however, such links between companies’ boards are not uncommon. In the EU, as well as in the different Member States,Footnote 2 there is no such express prohibition of interlocking directorates between competitors. Some economies have even been characterised by very dense networks of companies owing to multiple links among their boardsFootnote 3.

This chapter highlights the potential anticompetitive risks raised by interlocking directorates between competitors. The anticompetitive effects stem both from the increased ability to collude enabled by interlocks, as well as the reduced incentive to compete fiercely on markets characterised with numerous social and corporate links. In addition, this chapter touches upon the questions of conflict of interest and problems of directors’ independence that are inherent when a board member sits on the boards of two competing companies.

The main claim of this chapter is that there may be an enforcement gap around anticompetitive effects of interlocking directorates in Europe. Although Article 101 TFEU and EU Merger Control regulation theoretically apply to the coordinated and unilateral effects of interlocks, these provisions are of very limited use in practice. Company law in some Member States, such as France, limits the number of board appointments a director may hold, but such solutions are specific to certain types of companies and are largely insufficient to address the anticompetitive effects of interlocking directorates. Principles of corporate governance, such as fiduciary duties, are not binding and seem inappropriate to prevent anticompetitive effects and issues of conflict of interests.

Issues raised by interlocking directorates do not attract the attention they deserve and are notably absent from discussions on possible issues raised by financial links at the EU level.Footnote 4 In the US, the discussion about anticompetitive effects of common ownership should also grant more attention to interlocking directorates, particularly in the light of recent findings on the prevalence of interlocking directorates in the US.Footnote 5 This is because financial ownership links and interlocking directorates raise similar concerns, critically at the edge of competition law and corporate governance.Footnote 6 Therefore, this chapter draws attention on the need to tackle potentially significant issues that are currently largely undebated in Europe.

This chapter demonstrates that the anticompetitive effects of interlocking directorates (Section 10.1) may fall short of EU competition law (Section 10.2). Section 10.3 explains how interlocking directorates may be regulated in other jurisdictions, including in the US, and discusses whether tools of corporate governance may remedy the identified anticompetitive concerns (Section 10.4).

10.2 Anticompetitive Effects of Interlocking Directorates

Various studies highlighted that corporate networks across industries, based on interlocking directorates, have been particularly dense in continental Europe, although networks have tended to become less dense and more diffuse over the past decades.Footnote 7 These studies also demonstrate that corporate networks based on interlocks have been comparatively less dense in the US and in the UK.Footnote 8 Germany has long been characterised by dense networks of companies where banks play a central role, leading to the qualification of ‘cooperative capitalism’ as a feature of the German economy.Footnote 9 In France, large companies were typically connected through their boards with a high number of CEOs sitting as independent board members of competitors.Footnote 10 A recent study analysed the structure and evolution of corporate networks of the top 100 French, British, and German companies over a 14-year period (2006–2019). It found that although networks are composed of weaker links (individuals hold less appointments on average), they are wider in scope (more companies are now part of the networks).Footnote 11 While it does not specifically provide intra-sectoral information, this study demonstrates the existence of traditionally dense corporate networks in Europe comprising companies from the same industry. As explored by various corporate governance scholars, the existence of interlocking directorates may enhance the firm performance owing to the cognitive input of an experienced board member, and resource potential the link may create.Footnote 12

When held among competing companies, interlocking directorates may give rise to unilateral and coordinated effects.Footnote 13 The first impact on competition stems from the information and communication flows facilitated by interlocking directorates. Board members have access to strategic, accounting, and commercial information as well as information regarding the appointment and compensation of executives.Footnote 14 Information and communication between competitors have been shown to facilitate collusion, even when not specifically related to prices and quantities. Information flows may help in reaching a collusive agreement and also provide monitoring tools for competitors to prevent deviation from the collusive agreement.Footnote 15 As an example, a network of interlocking directorates has helped stabilise a number of cartels, including the international uranium and diamond cartels.Footnote 16 Accordingly, the purpose of the US prohibition of interlocking directorates is expressly to ‘avoid the opportunity for the coordination of business decisions by competitors and to prevent the exchange of commercially sensitive information by competitors’.Footnote 17 Anticompetitive agreements can also be facilitated by indirect interlocks where competitors sit on the board of a third party. Information exchanges can be more discrete with indirect rather than direct interlocks.Footnote 18

Interlocks may also affect unilateral incentives to compete. Social ties created by the attendance of common board meetings may discourage aggressive commercial strategies towards rivals. If interlocks are widespread within industries, this may reduce the overall intensity of competition.Footnote 19 When attached to financial interests, interlocking directorates may provide the ability to influence a competitor’s conduct. The remuneration schemes in place may also affect the incentive to compete, especially if closely tied to the firm’s performance.Footnote 20

Nevertheless, economic efficiencies are more likely to exist in the area of interlocking directorates than in the situation of minority shareholdings (e.g. where used to align incentives in joint ventures).Footnote 21 Information exchange, enabled by such links, may reduce strategic uncertainty which may under certain circumstances be pro-competitive if it improves business decision-making. The presence of the board member of a competitor offers the benefit of his expertise and experience which may improve decision-making. Moreover, the exchange of information can create synergies in the control and management of companies facing similar technical and economic issues. A business can also benefit from the reputation of an independent board member and use it in situations where the asymmetry of information may be an obstacle in negotiations to obtain financing from banks or investors. Similarly, the expertise and reputation of the board member of a competitor can facilitate contractual negotiations with suppliers and customers – especially in small businesses.Footnote 22

The anticompetitive effects of interlocking directorates are exacerbated if the corporate governance of the competing companies is weak. Directors sitting on several boards may influence the decision process in one company, as a way of favouring another company of which they are a board member. Directors may also be tempted to disclose confidential information of a company at another company’s board meeting. These issues may be mitigated by the quality of the fiduciary duty. A strong fiduciary duty, which indicates good corporate governance, may prevent the director from engaging in these types of practices. A director’s fiduciary duty to one company, however, may naturally conflict with their fiduciary duty in another company.Footnote 23 Overall, bad quality of corporate governance is more likely to induce directors with shared directorship to compete less aggressively.Footnote 24

10.2.1 Empirical Studies on Competitive Effects

The few existing empirical studies draw contrasting conclusions regarding the actual effectiveness of interlocks as a collusive device. Based on data of a sample composed of 225 firms convicted for participating in cartels between 1986 and 2010, Gonzales and Schmidt found that there is a greater likelihood of collusion when companies have a higher fraction of ‘busy’ board members, referring to members sitting on the board of other companies, owing to the impact of board connections on collusion.Footnote 25 Based on data of EU cartel cases between 1969 and 2012 and corporate links between the companies, a study by Hubert Buch-Hansen concluded that only 12 of the 3318 corporate ties among the 890 companies involved in the cartel cases seem to have been conducive to collusion. Three of them were direct and nine indirect interlocks. Interestingly, however, earlier cases of cartels seem to have been more correlated to interlocking directorates than today.Footnote 26 A possible interpretation is that since the 1990s, there is a stricter enforcement against cartel practices. Consequently, companies would refrain from using interlocking directorates to sustain collusion, possibly to avoid attracting the authority attention. Although inherent to the study of typically hidden illegal practices, the correlation was limited to cases of detected explicit collusion. This prevents any conclusion to be made on corporate links and undetected collusion between competitors. Based on estimation of the probability of detection (of cartels that were eventually detected), we can imagine that the population of undetected collusion largely outweighs that of detected cases.Footnote 27 A few older studies by Pennings and Burt based on US firms establish a positive correlation between an industry concentration and interlocks.Footnote 28 The latter study, however, found a negative relationship between interlocks and concentration, as of intermediate level of concentration. This may be explained by the fact that firms in highly concentrated industries have little need for interlocks to achieve collusive outcomes.Footnote 29

Finally, the following data further supports the idea that interlocks may have facilitated collusive agreements in the past.Footnote 30 Building on Connor’s statistics on international cartels between 1990 and 2009, I computed the rate of cartel recidivism according to the companies’ country of incorporation.Footnote 31 Among the 52 leading recidivist companies involved in international cartels, 17 companies originated in France and Germany, and those companies engaged in a total of 213 cartels. This means that French and German companies were liable for 35.3% of the international cartels in that period. In contrast, a total of nine UK and US companies, traditionally characterised by less dense corporate networks, were among the top cartel recidivists, engaging in a total of 88 cartels, which amounts to 14.6% of the international cartels accounted for.Footnote 32 Furthermore, France and Germany’s combined economies (reflecting possibly, the number of companies in it) amount only to 1/3 or the combined US and UK economies. Thus, weighing this, the proportion of French and German companies involved in cartels may appear to be comparatively even strongerFootnote 33.

Characteristics of the French and German industries, prone to cartel formation, surely plays a key role in explaining the substantial difference in cartel participation.Footnote 34 Corporate features, including dense corporate networks – particularly during the period covered by the statistics, may also explain the higher rate of cartel prosecution in France and Germany. Indeed, in Germany, it was suggested that corporate networks played a role as an ‘institutional infrastructure for coordination, information exchange, and control in Germany’.Footnote 35 In France, on top of interlocking directorates, during the 1990s and 2000s, cross-shareholdings among major companies increased, intensifying the network of corporate ownership.Footnote 36 Therefore, corporate ties that establish a ‘small world’ of corporations may have also been correlated with the multiple cartel convictions in France and Germany between 1990 and 2010.

10.3 The Reach of EU Competition Law Over Interlocking Directorates

In the EU, a structural link is scrutinised under the Merger Regulation if it is part of an acquisition that confers a ‘lasting change in the control of the undertaking’.Footnote 37 Interlocking directorates which are not part of an acquisition conferring control can be captured by Article 101TFEU only to the extent there is an agreement or concerted practice between undertakings, or by Article 102 TFEU if there is dominance.

10.3.1 EU Merger Control

According to the EU Merger regulation, ‘control shall be constituted by rights, contracts or any other means which, either separately or in combination and having regard to the considerations of fact or law involved, confer the possibility of exercising decisive influence on an undertaking, in particular by: (a) ownership or the right to use all or part of the assets of an undertaking; (b) rights or contracts which confer decisive influence on the composition, voting or decisions of the organs of an undertaking’.Footnote 38 Therefore, the existence of ‘decisive influence’ is central to the existence of control triggering the application of merger review. Interlocking directorates that confer influence are therefore theoretically part of merger control scrutiny. In addition, the Commission notice on remedies specifically addresses the removal of structural links, including financial or board links to remedy possible competition concerns raised by a merger.Footnote 39 The termination of interlocking directorships are thus examples of remedies imposed in the context of a merger raising competitive issues.Footnote 40 While the Commission and courts grasp the potential anticompetitive effects of structural links that do not confer control, such effects are unchallenged on a stand-alone basis.Footnote 41 The existence of an enforcement gap results from the reliance of EU merger review on the concept of control – which excludes from its scope structural links that do not confer control. relation.

10.3.2 Article 101TFEU

The main obstacle to the application of Article 101 TFEU to capture the effects of interlocking directorates is distinguishing a unilateral from a joint conduct, through the finding of an agreement or a concerted practice.Footnote 42 If the nomination of a board member emanates from an appointment by the general assembly of shareholders, this will not constitute an agreement between undertakings. Yet, if the right to nominate a board member is part of a shareholding agreement, the board nomination may constitute an agreement between undertakings and therefore fall within the Article 101(1) TFEU prohibition.Footnote 43

A relevant question is whether flows of information stemming from interlocking directorates could fall within the scope of Article 101 TFEU. The mere exchange of information between competitors can be an object restriction of competition, if the information relates to individualised and future price information.Footnote 44 In practice, to what extent could strategic information received at a board meeting, be in breach of Article 101 TFEU? In Suiker Unie, the Court established that Article 101 TFEU ‘preclude[d] any direct or indirect contact between [competitors], the object or effect whereof is either to influence the conduct on the market […] or to disclose to such competitor the course of conduct which they themselves have decided to adopt or contemplate adopting on the market’.Footnote 45 In addition, Hüls provides that the presumption that competitors take into account the information in determining their conduct is even greater ‘where the undertakings concert together on a regular basis over a long period’.Footnote 46 Therefore, the nature of the contact is irrelevant as long as such contact produces an anticompetitive effect. A concerted practice may exist even in the event of a passive reception of information, provided that there is reciprocity of acceptance.Footnote 47 Interlocking directorates may amount to a direct and close contact between undertakings. Depending on the nature of the information disclosed at the occasion of board meetings, and the manner in which it is circulated within the companies, such conduct can in principle meet the requirements of a concerted practice.

Having a common board member does not bring the two companies within the same economic entity. Therefore, information exchange between those two companies cannot be considered as an intra-corporate relation precluding the application of Article 101 TFEU.Footnote 48 It is, however, difficult to consider that the mere exchange of information during a board meeting, which is internal to the company, can be sufficient to establish a concerted practice. To my knowledge, there is no case where a concerted practice was identified in such context, reflecting the practical difficulty for competition authorities to produce tangible evidence of a concerted practice based on the mere existence of structural links.Footnote 49 In sum, Article 101 TFEU theoretically applies to an information exchange related to structural links, but the establishment of an agreement or concerted practice between undertakings may prove difficult.Footnote 50

10.3.3 Article 102 TFEU

In addition, anticompetitive effects could be reviewed in the context of collective dominance, the abuse of which may also be in breach of Article 102 TFEU.Footnote 51 Collective dominance can exist when economic links between undertakings make them together hold a dominant position vis-à-vis other competitors on the same market.Footnote 52 In Irish Sugar, a situation of collective dominance was established based on a combination of economic and corporate ties between two companies, including interlocking directorates.Footnote 53 Therefore, anticompetitive effects of structural links falling short of Article 101 TFEU could be theoretically be reviewed under Article 102 TFEU even if undertakings are individually not dominant, provided there is an ‘abuse’ of this collective dominance. The main difficulty would be, however, to establish an abuse of that position of collective dominance. To date, there are only very few cases of collective dominance. One of the reasons is that anticompetitive issues raised in such cases may not fit the analytical framework and legal standards developed in cases of single undertaking abuses, more focused on exclusionary conduct. Cases of collective dominance based on structural links would, instead, be exploitative types of abuses, typically involving higher prices, which are far more difficult to establish.Footnote 54

To sum up, limits to applying Article 101 TFEU relate to the difficulty of finding an agreement between undertakings as the corporate relation may not be reciprocal. Coordinated effects stemming from information flows may be caught, but to date, there is no case of violation based on the type of information usually communicated within the private remit of a board. Article 102 TFEU potentially enabling an extension of the concept of influence to capture non-coordinated effects only applies in the context of dominance. Collective dominance may provide a better avenue to control the negative impacts of structural links in concentrated markets; this would, however, require willingness from the Commission to re-open excessive prices line of cases.

10.4 Interlocking Directorates in Other Jurisdictions

10.4.1 In the US: a per se Prohibition

In the US, interlocking directorates are subject to a specific provision. Section 8 of the Clayton Act prohibits any ‘person’ from simultaneously serving as a director or officer of two competing corporations.Footnote 55 The degree of competition required for the application of Section 8 is such that its elimination ‘by agreement between [the companies] would constitute a violation of any antitrust laws’.Footnote 56 Section 8 prohibition only applies to companies of a certain size.Footnote 57 In addition the section does not apply when the overlap between the competing companies is de minimis.Footnote 58

The US has a particular approach to interlocking directorates. A specific provision on the issue of interlocking directorates only exists in very few jurisdictions.Footnote 59 In addition, those jurisdictions enable the interlock to be justified based on a lack of competitive injury, which contrasts with the per se prohibition in Section 8.Footnote 60 A brief historical background sheds some light on the US antitrust peculiarity. The introduction of Section 8 in 1914 is closely related to concerns about monopolies in a period of broad public mistrust in business.Footnote 61 Following a proposal by the Democratic Party in 1908, all three political parties called for legislation on interlocking directorates in 1912. In that context, several reports were issued to publicise the scope of interlocking directorates in sectors, such as the railroad and steel markets, as well as in financial institutions.Footnote 62

Section 8 is the outcome of a political and legislative process, largely influenced by the work of Louis Brandeis, advisor to President Wilson. His position with regard to the harm created by interlocking directorates was as follows:

The practice of interlocking directorates is the root of many evils. It offends laws human and divine. Applied to rival corporations, it tends to the suppression of competition and to violation of the Sherman law. Applied to corporations which deal with each other, it tends to disloyalty and to violation of the fundamental law that no man can serve two masters. In either event it tends to inefficiency, for it removes incentives and destroys soundness of judgment. It is undemocratic, for it rejects the platform: ‘A fair field – and no favors’ – substituting the pull of privilege for the push of manhood.Footnote 63

In an address to Congress, President Wilson defended the necessity for stricter antitrust laws with the necessity to ‘open the field to scores of men who have been obliged to serve when their abilities entitled them to direct’. Interlocking directorates were then perceived as an obstacle to the opportunities that the American economy was supposed to provide.Footnote 64 Therefore, much broader concerns than unilateral and coordinated effects, also including the issue of conflicts of interests between shareholders and directors, drove the introduction of Section 8. The Act finally adopted in 1914 reflected a narrower approach taken by Congress to limit the scope of the prohibition to certain types of interlocks.Footnote 65 The last amendment of the Act, in 1990, was aimed at providing greater exceptions to the per se prohibitions (raising the jurisdictional threshold and exempting interlocks having de minimis overlap) while extending the prohibition to officers in addition to directors.Footnote 66 Section 8 of the Clayton Act is enforced by counsels to corporations, and there has been very little litigation.Footnote 67 Private litigation cases show that Section 8 is closely related to issues of corporate governance. Claims have typically been lodged by corporations in order to prevent an acquisition or proxy fight, or to remove an interlocked director; they have also been brought by shareholders of an alleged interlocked company to reject a merger or in support of a derivative action.Footnote 68 Recent investigations by the FTC led, for example, to the resignation from the board of Google of Arthur Levinson, a member of Apple’s board. Google’s CEO Eric Schmidt, who was director of both companies, stepped down from Apple’s board.Footnote 69 In 2016, the DOJ obtained the restructuring of a transaction that would have given a company the right to appoint a member on its competitor’s board.Footnote 70

In addition, anticompetitive effects of interlocking directorates that may not be reached by Section 8 can be reviewed under Section 1 of the Sherman Act as well as under Section 5 of the Federal Trade Commission Act.Footnote 71 A specific historical and economic context in which the US provision emerged explains the far-reaching prohibition of interlocking directorates between competitors, irrespective of whether they actually harm competition.

Recent evidence shows, however, that interlocking directorates persist (and even tend to increase) despite this far-reaching prohibition. A study by Nili of 1500 S&P US companies over the years 2010–2016 demonstrates that intra-industry links are very common.Footnote 72 It shows that, in 2016, around 25% of companies shared at least one common board member with a company operating in the same narrowly defined sector (corresponding to one code of the SIC/NAICS classification systems). These links constitute potential Section 8 violations.Footnote 73

10.4.2 Interlocking Directorates in EU Member States

In EU Member States, the problem of interlocking directorates is rather a matter of corporate law. In France, the French Commercial Code governs different aspects of the composition and functioning of the board of directors of limited companies.Footnote 74 The law limits the number of seat appointments held as top executive or board member to five. In addition, the ‘Macron law’Footnote 75 has reduced that number to three appointments for publicly listed companies of more than 5,000 employees in France, or at least 10, 000 worldwide.Footnote 76

Italy is the only country having adopted a specific regulation entitled ‘Protection of competition and cross corporate ties in the banking and finance industry’ to deal with the anticompetitive effects of interlocks among competitors.Footnote 77 In 2011, following a report of the competition authority on problems of corporate governance and competition in the financial industry, Italy adopted a series of specific economic measures.Footnote 78 These measures aim at increasing competition and ethical governance in industries where low economic performance seemed to stem from the multitude of personal ties linking corporate governance bodies.Footnote 79 This regulation prohibits any person appointed as a manager, supervisor, or auditor of a company operating in the financial and insurance industry, from holding a similar appointment with a competitor. Persons holding more than one such appointment must comply within 90 days and decide which one to keep. Failure to comply leads to the termination of all appointments, either by the company or by the national regulator.Footnote 80

With the exception of Italy in the banking and financial industry, limitations of interlocking directorates do not specifically target competitors. These tools, existing at the national level in a few EU Member States, offer a variety of different solutions and have, in practice, a limited impact on cross-border operations.

10.5 Principles of Corporate Governance

Structural links are at the heart of corporate governance systems. This section discusses whether principles of corporate governance can set constraints over the anticompetitive effects of interlocking directorates. Competition law may adjust its boundaries to address common issues that corporate laws and corporate governance fail to address. This overall shows that the discussion at the EU level require a multi-disciplinary approach to the issue of interlocking directorates.

While protection of minority shareholders and the freedom to appoint board members are essential to corporate governance, these corporate arrangements can also hinder rivalry between companies. In addition, policies regarding corporate governance encourage an active role by institutional investors in the corporate governance, which seems to conflict with the competitive concerns raised by common ownership.Footnote 81

Yet, corporate governance and competition law seem to converge on other issues. A core principle of corporate governance is the fiduciary duty of management to shareholders.Footnote 82 Fiduciary duty may mitigate the anticompetitive effects of structural links. In the context of interlocking directorates, a strong fiduciary duty may prevent a common board member from disclosing information from one company to the other. However, a director’s fiduciary duty to one company may naturally conflict with their fiduciary duty to another company.Footnote 83

Independence of decision-making is another important principle of corporate governance.Footnote 84 Accordingly, decisions should be made in the company’s best interest, without consideration of other companies.Footnote 85 The French Asset Management Association warns against the risk of interlocking directorates as undermining transparency and independence of decision-making, unless associated with a strategic economic alliance.Footnote 86 In practice, however, an increase in price taken in the interest of a competitor may be difficult to identify. Collecting evidence and taking action, such as voting to remove a director in breach of a fiduciary obligation, could be difficult and risky for the shareholders. Further exploration of corporate governance mechanisms is therefore critical to understanding the practical ability of a board to raise prices unfavourably for the company, for the financial benefits of a competitor.Footnote 87

As an example, the French Court of Cassation reaffirms the legal requirement of fiduciary duty for top executives, which then applies to those sitting on the board of a competing company. In addition, the court clarified that this duty forbids the chief executive from commercial negotiation in his capacity as manager of another company within the same industry.Footnote 88 However, such requirement, rather limited to apprehend the whole spectrum of anticompetitive effects, only applies to executives (and not to all directors) of French companies. In addition, the code of corporate governance recommends that as an ethical rule, a board member should be bound to report to the board any actual or potential conflict of interest, and refrain from voting on the related resolution.Footnote 89 Although no express mention is there made of conflicts of interests arising from individuals sitting within multiple board meetings, generic rules on conflicts of interest are likely to encompass such instances.

Interlocking directorates may pose additional problems both for corporate governance and competition law, if top managers favour the selection (or exclusion) of board members based on how passive (or active), they are on other boards, in an effort to retain control over the board.Footnote 90 In addition, mutual interlocks can reflect and contribute to CEO entrenchment, resulting in higher compensation and lower turnover.Footnote 91

10.5.1 Conclusion: Competition Law ‘stepping in’?

Legal constraints provided by corporate laws do not bridge the regulatory gap that exists at the EU level. General principles of corporate governance, such as independence of decision-making, have a limited ability to address competitive concerns, even when they closely relate to common issues. In Italy, for example, a competition approach may have stepped in to address issues that corporate governance modernisation has so far insufficiently addressed.Footnote 92 Some have argued that interlocking directorates should remain beyond the realm of competition law.Footnote 93 Corporate laws of Member States may provide effective ex ante solutions to the problem, especially if the practice of interlocks primarily has national features. The need of an EU-wide solution also depends on whether there is a growing tendency for cross-border interlocking directorates.Footnote 94 If an EU-wide regulation prohibiting interlocks among competitors may seem too ambitious, significant limitations of interlocking directorates could be introduced nationally to remedy issues that are of concern for both corporate governance and competition law. In any case, a comprehensive impact assessment of the extent of such issues in Europe should form part of any proposal for reform and would supplement the identification of theoretical concerns provided here.Footnote 95 Finally, the issues of common ownership, currently highly debated especially, and that of interlocking directorates, should be approached jointly.Footnote 96 They raise similar competitive concerns and solutions to remedy those are critically at the junction of competition law and corporate governance. Mapping corporate networks created by both types of structural links would illuminate this debate.

11.1 Introduction

In this chapter, we provide an overview of the Italian legislation on interlocking directorates and its enforcement in the last decade. Italy has introduced an anti-interlocking provision to promote competition in the banking, insurance, and financial sectors. Even if it is not easy to make comparisons with other EU Member States, many studies claimed that the number and relative dimension of the Italian financial companies linked by interlocking directorates were greater than in other Member States.Footnote 1 This is why, in 2011, in the aftermath of a very harsh financial crisis, Italy enacted a statutory provision forbidding the simultaneous appointment of the same person to the board of directors (or to other corporate bodies)Footnote 2 of two or more competing financial companies.

After explaining why, without regulation, these personal ties may facilitate or reinforce the achievement of a collusive or quiet life equilibrium among competitors, we provide a brief description of the main features and scope of the 2011 Italian interlocking ban. We then attempt to evaluate its effectiveness and limits. Using the banking sector as a case study, we gathered data on the number of interlocking directorates that persisted among the 25 largest banks and banking groups in Italy at the end of 2018. The result of our study is that interlocking directorates among major Italian banks seem to have disappeared. This is at odds with the prevailing empirical literature which has claimed that interlocking directorates are still a widespread reality of Italian capitalism, with possible persisting anticompetitive effects in many markets. To counter this claim, we also considered some empirical studies showing that, in the period following the entry into force of the interlocking ban, bank lending rates fell, which suggests more vigorous competition.