Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- List of Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Digital Facsimiles of Frequently Cited Manuscripts

- The Contents of Oxford, Bodleian Library, Digby 86

- Note on the Presentation of MS Digby 86 Texts

- Introduction

- 1 Fellow Travellers with Saint Nicholas

- 2 Anglo-Norman Religious Instruction in MS Digby 86: Echoes of Lateran IV

- 3 Latin and Vernacular Prayers in MS Digby 86

- 4 Science, Medicine, Prognostication: MS Digby 86 as a Household Almanac

- 5 Literary Therapeutics: Experimental Knowledge in MS Digby 86

- 6 Petrus Alfonsi, the Disciplina clericalis and Le Romaunz Peres Aunfour of MS Digby 86

- 7 Misogyny in MS Digby

- 8 Gender Trouble? Fabliau and Debate in MS Digby 86

- 9 The Middle English Poetry of MS Digby 86

- 10 MS Digby 86 and Thirteenth-Century Scribal Poetics

- 11 The Scarlet Letter: Experimentation, Design and Copying Practice in the Coloured Capitals of MS Digby 86

- 12 Below Malvern: MS Digby 86, the Grimhills and the Underhills in their Regional and Social Context

- Bibliography

- Index of Manuscripts Cited

- General Index

- Manuscript Culture in the British Isles

1 - Fellow Travellers with Saint Nicholas

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 24 October 2019

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- List of Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Digital Facsimiles of Frequently Cited Manuscripts

- The Contents of Oxford, Bodleian Library, Digby 86

- Note on the Presentation of MS Digby 86 Texts

- Introduction

- 1 Fellow Travellers with Saint Nicholas

- 2 Anglo-Norman Religious Instruction in MS Digby 86: Echoes of Lateran IV

- 3 Latin and Vernacular Prayers in MS Digby 86

- 4 Science, Medicine, Prognostication: MS Digby 86 as a Household Almanac

- 5 Literary Therapeutics: Experimental Knowledge in MS Digby 86

- 6 Petrus Alfonsi, the Disciplina clericalis and Le Romaunz Peres Aunfour of MS Digby 86

- 7 Misogyny in MS Digby

- 8 Gender Trouble? Fabliau and Debate in MS Digby 86

- 9 The Middle English Poetry of MS Digby 86

- 10 MS Digby 86 and Thirteenth-Century Scribal Poetics

- 11 The Scarlet Letter: Experimentation, Design and Copying Practice in the Coloured Capitals of MS Digby 86

- 12 Below Malvern: MS Digby 86, the Grimhills and the Underhills in their Regional and Social Context

- Bibliography

- Index of Manuscripts Cited

- General Index

- Manuscript Culture in the British Isles

Summary

WITHIN the small corpus of bilingual and trilingual manuscripts compiled in England in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, Oxford, BodL, Digby 86 remains one of the most puzzling for modern sensibilities. John Frankis's 1985 study outlines the manuscript's juxtaposition of high and low styles, prose and poetry, its subject matter being both devotional and scurrilous, lyrical and scientifically technical, along with the pragmatically useful (a calendar for religious use) and the speculative (prognostications, charms, dream interpretation). Calling Digby 86's contents ‘eccentric’ and ‘extravagantly heterogeneous’, Frankis deduces that it was addressed to an audience who sought both religious instruction and entertainment, in a society that included both secular clergy and the laity, and which was ‘somewhat naïve and even coarse in taste, rustic rather than urban’. He argues that ‘Digby 86, more than any other manuscript of the period, gives us an insight into what one might loosely call the upper middle class of thirteenth-century rural England’.

Frankis's broad overview of Digby 86 is persuasive, yet for me several questions persistently remain. How are we to read these widely different texts? What additional inferences can be made regarding the scribe/compiler's purpose in creating this book? What do the contents imply about the social and literary milieu of its audience? Are there distinctive linguistic features of scribal usage in French?

Roughly half of the contents in the 207 folios of Digby 86 are in French, but only two works explicitly mention the use of French. These are Les Miracles de seint Nicholas by Wace (art. 54; fols. 150ra–161ra, datable to the mid-twelfth century) and Le Romaunz de temtacioun de secle by Guischart de Beauliu (art. 63; fols. 182v–186v, datable to the end of the twelfth century).

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

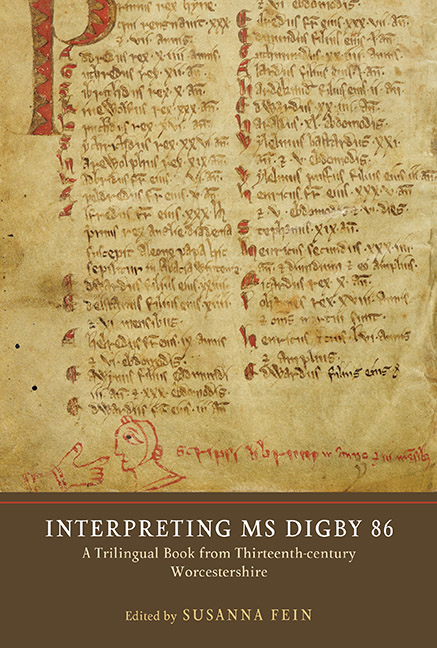

- Interpreting MS Digby 86A Trilingual Book from Thirteenth-Century Worcestershire, pp. 10 - 24Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2019