6.1 Introduction

If you attend a Conference of the Parties (COP) to a multilateral environmental agreement or the meetings of an intergovernmental science body, you will no doubt be caught up in the intrigue of the plenary debates and contact group discussions focused on substantive issues and national obligations to take action. Will the parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) adopt a new global biodiversity framework when the ten-year agenda, as set out in the Aichi Targets, comes to a conclusion? Will the parties to the Paris Agreement on climate change under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) finalize the rules on how countries can reduce their emissions using international carbon markets, as covered under Article 6? Will parties to the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) include land tenure as a new thematic area under the convention? Will the latest scientific assessment be adopted by the IPCC or the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) and clearly define human responsibility for causing and redressing global challenges?

While these headline agenda items will command most participants’ attention, tucked away in parallel discussions, a small group of state delegates will be focused on the program and budget, with the aim of developing what will likely be the final set of decisions adopted at that meeting. The decisions of this group are essential to the operations of the convention or organization: Without an affirmative conclusion by this group, the lights will not remain on, the secretariat staff will not be paid, and the next meeting will not take place. In short, global cooperation through this forum cannot continue until this small group reaches agreement.

Member states to multilateral environmental agreements and intergovernmental science organizations establish secretariats to undertake a number of tasks required for their efficient operation. A central area of responsibility for secretariats is the organization of meetings of the COP or plenaries and other meetings of relevant subsidiary bodies, during which member states negotiate the ongoing work and focus of the treaty or organization, including the budget that funds the secretariat’s activities over the subsequent year(s). A close examination of the decision-making process around these budgets offers a window into the principal–agent relationship between state parties and secretariats. State control of the purse strings is an important mechanism through which the principals in these intergovernmental organizations control the activities of their agents: Through their decisions on programs and budgets, states assert control over the focus of activity and level of ambition that secretariats can undertake. This chapter explores the dynamics and decisions taken regarding the secretariat budgets to shed light on this underexplored perspective in the principal–agent relationship. While the other contributions to this volume explore the ways that secretariats and international organizations can act independently of states, we explore one of the primary ways that states exercise control over secretariat activities.

We examine this relationship through case studies that consider budget-related decision-making processes and outcomes under the Rio Conventions – UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, Convention on Biological Diversity, and UN Convention to Combat Desertification – and two multilateral scientific bodies – the IPCC and the IPBES. The negotiations on the program and budget for the Rio Conventions reveal ways in which member states seek to control the activities of the secretariats through the budget structure. We also review the responses to budget crises by the secretariats of the scientific bodies and their members. The research draws on our participant observations of multiple multilateral environmental agreement (MEA) negotiations,Footnote 1 as well as the final decisions of the meetings we analyze. Before launching into the case studies, we begin the chapter with a review of the principal–agent literature as it applies to the cases we explore. The conclusion comments on what the cases suggest for the principal–agent relationship in multilateral environmental organizations.

6.2 Principals, Agents, and Resources

According to Biermann et al. (Reference Biermann, Siebenhüner, Biermann and Siebenhüner2009: 6), international bureaucracies are “agencies that have been set up by governments or other public actors with some degree of permanence and coherence and beyond formal direct control of single national governments … and that act in the international arena to pursue a policy.” In other words, they are a hierarchically organized group of international civil servants with a given mandate, resources, identifiable boundaries, and a set of formal rules and procedures within the context of the establishing treaty, protocol, or charter. But what is “given” may be taken away, or at least restricted or redirected, albeit with a time lag built around annual or biennial decision-making at conferences of the principals.

The principal–agent focus is particularly useful for examining the relationship between member states and secretariats, as a special type of international organization that exists to administer a treaty or agreement. Principal–agent theory developed initially in the area of business studies focusing on the delegation processes within firms. It was later applied to US Congressional politics and European integration studies and has since been used in studies on international organizations (Bauer et al. Reference Bauer, Biermann, Dingwerth, Siebenhüner, Biermann and Siebenhüner2009: 26–27; Elsig Reference Elsig2010). When applied to secretariats, principal–agent theory highlights the fundamental differences in the collective interests of national governments as the principals and the secretariats as the agents. It maintains that secretariats are able to develop autonomy from their principals and thus need to be understood as actors in their own right. In this perspective, secretariats can be seen as self-interested bodies that are predominantly interested in increasing their individual resources and competencies. Bauer et al. (Reference Bauer, Biermann, Dingwerth, Siebenhüner, Biermann and Siebenhüner2009: 27) indicate that the activities of secretariats need to be explained on the basis of their relationship to national governments that delegate authority to secretariats. Principal–agent theory can offer theoretical models to reveal the general influence of secretariats, as well as limits thereof, keeping in mind that the relationship between the principal and the agent is not fixed. The evolution of the relationship can be tracked by observing the program and budget negotiations.

The principal–agent concept is particularly on display when it comes to decisions on financing and budgets. Barnett and Finnemore (Reference Barnett and Finnemore2004: 12) suggest that the study of international organizations as bureaucracies “puts the interactive relationship between states and IOs [international organizations] at the center of analysis” rather than assuming that states dictate to international organizations. But while their examination concludes that international organizations exercise behavioral autonomy from states, they recognize that states “provide the delegated authority and resources” for these organization, although “mechanisms of accountability have not kept pace with the power and reach of international organizations” (Barnett and Finnemore Reference Barnett and Finnemore2004: 170–171). The budget negotiations we focus on represent an accountability mechanism, albeit with a time delay, as they often take place on a two-year cycle.

An international public administration (IPA) focus, as presented in the introduction to this book, brings attention to the ways in which resources enter into the principal–agent relationship. This chapter considers the fourth of five sources of IPA influence, as identified by Bauer, Knill, and Eckhard (Reference Bauer, Knill, Eckhard, Bauer, Knill and Eckhard2017: 182–189). Budgetary restrictions can be mechanisms of accountability through which principals limit or direct the activities of their agents. The examples of states establishing restrictions on how resources can be used, as presented in this chapter, reveal that this mechanism is as much a reaction to perceived overreaches by secretariats as it is a proactive set of guidelines for the principal’s preferred direction.

In the conclusion to their study of secretariat influence, Biermann and Siebenhüner (Reference Biermann, Siebenhüner, Steffen, Biermann and Siebenhüner2009: 330–333) distinguish among polity competence, resources, and embeddedness as some of the variables that help explain variation in the influence of international bureaucracies. They conclude that “there is no clear link between the availability of funds and the autonomous influence of bureaucracies” (Biermann and Siebenhüner Reference Biermann, Siebenhüner, Steffen, Biermann and Siebenhüner2009: 338), but this conclusion does not explore the give and take between the principal and agent in setting and resetting the availability of funds. We agree with Biermann and Siebenhüner (Reference Biermann, Siebenhüner, Steffen, Biermann and Siebenhüner2009: 345) that “international bureaucracies are autonomous actors in world politics.” Their principals’ decisions on their programs and budgets would not be as belabored or respond to specific initiatives, as discussed later, if they were not. But while the accountability mechanism of the budget decisions cannot explain why one secretariat might be more ambitious (and influential) in its efforts to bring new activities into its program of activities than another, the possibilities for secretariat influence depend on its ability to mobilize resources for a particular activity. Biermann and Siebenhüner assign a lower importance to the polity – or legal, institutional, and organizational framework, including resources – than to the problem structure and the people and procedures of a given bureaucracy to explain variations in influence among secretariats. We suggest taking a closer look at the decisions taken around resources.

This chapter examines variables involved with the decision-making processes on resources as a mechanism of accountability and regulation of secretariat influence. The next section offers a short introduction to the funding sources and budgeting process for secretariats. It is followed by case studies related to program and budget decision-making under the Rio Conventions and the two multilateral scientific bodies.

6.3 Funding Avenues for Secretariats

In the UN system, funding has traditionally come from two sources: assessed and voluntary contributions. A system of assessed contributions requires member states to make financial contributions – or dues – as an obligation of membership. For example, the United Nations assesses mandatory contributions or dues to all members using the capacity-to-pay principle set out in the Charter of the United Nations, which takes into account the size of their economy (Graham Reference Graham2015). The UN scale of assessments is modified by a ceiling and a floor placed on the proportion any single member state can pay to guard against tendencies by member states “to unduly minimize their contributions” or increase them unduly for prestige (UN General Assembly 1946, A/80). The United Nations General Assembly adjusts the scale of assessments every two years, and many UN specialized agencies and treaty bodies, including the Rio Conventions, use the United Nations General Assembly scale.

Voluntary contributions are usually considered to be extrabudgetary funds paid in order to finance specific operations or services (Francioni Reference Francioni2000). Unlike assessed funding, there is no legal obligation attached to voluntary funding systems (Archibald Reference Archibald2004). These systems lack the authority to allocate funding requirements across members, which leaves each member state with the ability to determine whether and how much to contribute. As a result, member state support for intergovernmental organizations funded by voluntary contributions can vary widely, with some gaining near universal support and some funded by a minority of members (Graham Reference Graham2015). So while the relevant organization may adopt a budget every year or two, the actual funds received are determined by the individual donors. This creates a challenge for the secretariats that are often mandated by the member states to implement a work program but do not know from year to year whether they will have sufficient funds to do so and may have the added task of convincing individual member states or other donors to fund the voluntary portion of the budget. The biggest UN funds and programs – the United Nations Children’s Fund, the United Nations Development Programme, the United Nations Population Fund, and the World Food Programme – are funded entirely by voluntary contributions.Footnote 2

Further restricting the flexibility of secretariats is the fact that voluntary funds can often be “earmarked” for a particular purpose. Earmarked funding is provided by member states with conditions placed on the use of the funds. The practice of earmarking grew substantially in the 1990s, and by 2013, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD Reference Mead, Cardenes, Gutiérrez and Woods2015), the weight of funding to multilateral organizations that is earmarked for specific purposes, countries, or sectors represented 31 percent of total funding, with UN funds and programs receiving 76 percent of all funding as earmarked funds. A recent study finds the “growth in earmarked funding continues to outpace that in core funding” (Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation and UN Multi-Partner Trust Fund Office 2018: 10) and highlights that such funding is less flexible than core contributions, introducing questions for any inquiry of the ability of a secretariat to influence policy directions.

Unlike the Rio Conventions, the IPCC and IPBES Secretariats are charged with producing scientific assessments on climate change and biodiversity/ecosystems services, respectively, and serve as intergovernmental science–policy interfaces. Also unlike the Rio Conventions, their budgets do not use the UN scale of assessments but rely entirely on voluntary contributions. The IPCC and IPBES procedures do not define any level of annual financial contribution each member state or observer organization must pay to support the budget and work program or the travel expenses for participants from developing countries and countries with economies in transition (IPCC 2017a).

With regard to private actors, Graham (Reference Graham2017) notes that as assessed contributions were supplemented by voluntary contributions, private actors also became eligible contributors. Like member states, private actors, including nongovernmental organizations, philanthropic organizations, and multinational corporations, often earmark their funding for specific purposes. For example, in 2015, specified voluntary contributions from foundations, corporations, and civil society to the UN system amounted to about USD 4 billion, or 14 percent of all specified voluntary contributions to the UN system (United Nations Reference Seitz and Martens2016). However, these trends primarily affect the UN development agencies (see Graham Reference Graham2017; Seitz and Martens 2017).

As we explore in the next section, the process used to reach a decision on the amount of funding to be provided to an intergovernmental organization through assessed and voluntary sources is a function of the relationship between the principals (member states) and the agents (secretariats).

6.4 Push and Pull for Control in Programs and Budgets

The cases presented in this section explore the relationship between secretariats and parties from a number of angles. At each point, we find decisions made by the parties that directly or indirectly addressed or diminished the secretariat’s initiatives.Footnote 3 We begin with an example that demonstrates a basic starting point in the principal–agent relationship: If the parties do not adopt a budget, the secretariat will cease to operate. This first case study also introduces a key focus of parties during budget negotiations: limiting the percentage increase in the budget rather than matching it to the level of programming required to achieve other decisions under negotiation at the same COP. This exploration provides background for reviewing the action and reaction from secretariats and parties in response to the increased level of programming secretariats have been assigned. When secretariats have presented parties with draft budgets that would significantly increase their funding, parties have responded by adopting guidelines for future budget proposals that restrict the percentage increase those future budgets can incorporate. We then review the level of assessed and supplementary budget components over time for the three Rio Conventions, noting that the former has been consistent within each convention and across the three conventions and the latter has been the source of fluctuation. Finally, we present the experience of IPCC and IPBES in the face of budget shortfalls, to which the parties ultimately responded with funding rather than cede control based on the requirements of unconventional funders.

Parties Control the Switch to Keep the Lights On

At its most basic, the continued operation of the secretariat is on the line with each budget negotiation. A COP may decide to push a decision on reducing emissions or cooperating on biosafety issues to the next meeting if the parties cannot reach an agreement. But if the budget is not adopted, the organizing entity for that next meeting – the secretariat – will not be able to operate. Without a budget, funds will not be allocated for secretariat staff salaries, office requirements, and preparations for the next meeting of the COP. This point was illustrated during the negotiations for the eighth session of the UNCCD COP, which took place in September 2007 in Madrid, Spain.

During this UNCCD COP, a Japanese delegate had consistently, but not forcefully, voiced his country’s position that the overall budget should be the same as for the previous biennium: zero nominal growth. The program and budget contact group was meeting in parallel to the negotiations on the new strategy for the convention, which the parties had called for to help define the convention’s purpose and guide its approach to combatting drought, land degradation, and desertification. In addition, the convention had just undergone a change in leadership. The first executive secretary had had a combative relationship with developed country parties over the role of the secretariat in implementation activities, which had manifested itself in budget decisions that sought to control the secretariat’s scope (Wagner and Mwangi 2010). Despite the Japanese delegate’s position, the draft budget decision that was sent to the closing plenary in Madrid provided for a 5 percent increase in the euro value of the budget, with clear secretariat support. However, the Japanese delegate had only agreed to the proposal ad referendum in a contact group.Footnote 4 While many delegates left the conference center because they expected the final adoption of decisions to be without incident, the Japanese delegate contacted his capitol and was instructed not to accept the draft budget (Conliffe et al. Reference Conliffe, Mwangi, Wagner and Xia2007). General chaos ensued through an all-night scramble to determine what would happen next.

The solution was to hold an extraordinary COP before the end of the year, at UN headquarters in New York, to adopt a budget. However, the negotiations continued along the same lines during that one-day event, with Japan holding to its position of zero nominal growth. It became evident that this country desired to set a precedent for other MEA budget negotiations that year. Ultimately, UNCCD delegates adopted a budget with a 4 percent increase, although 1.2 percent of it (EUR 185,000) was to be met, “without creating a precedent for this or any other convention,” by the government of Spain (which held the COP presidency) as a way to break the deadlock. With this compromise, the negotiations concluded at 4:00 a.m., and the secretariat’s lights remained on for two more years (Chasek Reference Chasek2007: 2).

The UNCCD COP8 budget negotiations illustrate the principal’s ultimate authority over maintaining a functioning agent. While these talks were held up by one party, the consensus required for all Rio Convention outcomes could be similarly impeded by any number of parties. The reactions of MEAs to the restrictions on global meetings due to the global COVID-19 pandemic reinforce this point. While the pandemic resulted in the postponement of many COPs, parties convened extraordinary COPs using the “silence procedure” to adopt programs and budgets in order to keep the secretariats functioning until global meetings could resume (see, e.g., Sollberger Reference Patz, Goetz, Bauer, Knill and Eckhard2020).

Reigning in Secretariat Budget Proposals

The focus of parties on limiting the growth of the core budget, regardless of the level of ambition in the substantive expectations for the convention’s program for the biennium, can be further illustrated by the experience of the 2009 UNCCD COP, which took place in Buenos Aires two years after the protracted budget talks in Madrid. This COP followed the adoption of this MEA’s new ten-year strategy. Despite the fact that these talks also came on the heels of the financial crash, the executive secretary attempted to set the tone for the budget discussions by presenting a proposed budget with a 16 percent increase over the previous biennium. Negotiators who had come into the talks with instructions to hold the growth of the budget to a much lower percentage were not prepared to engage in a discussion of this proposal, and were even concerned with whether the executive secretary was in touch with the political environment in which he needed to operate. Negotiations focused on three options to increase the budget (5 percent, 4.29 percent, and 3.36 percent), none of which was close to the secretariat’s proposal. Negotiators eventually settled on the middle option (Aguilar et al. Reference Aguilar, Conliffe, Russo, Wagner and Xia2009).

Negotiations on the budget are often hampered by differences in participants’ approaches to framing the proposed budget increase. Resulting tensions may exist between developing and developed country parties as well as between the member states and the secretariat. As noted, many of the parties will enter the budget negotiations with instructions from their government regarding an acceptable percentage increase (or lack thereof) over the budget adopted for the prior year or biennium. At the same time, the negotiators are facing the challenge that parallel negotiations regarding the programs and projects that the secretariat will be asked to implement are taking place, and the budget negotiations should provide the resources for those programs and projects. These competing priorities and influences on budget negotiations can lead to a disconnect between the ultimate decision on the budget and the substantive decisions adopted by the COP. Behind the scenes at the third CBD COP, for example, the executive secretary developed a tally of the estimated cost for each decision as it was adopted, but rumor has it that he decided not to share the information with delegates because the tally had far overtaken the budget level under discussion in the program and budget contact group (Carpenter et al. Reference Carpenter, Chasek and Gardner1996).

The secretariat, although officially not a party to the negotiations, often leads the messaging about the need to connect the budget with the ambition identified in the substantive decisions, beginning with the background documentation prepared for the COP. The secretariat tables what serves as a starting point for the budget negotiations in its background documentation provided to the parties. As in any negotiation, this proposal can frame the negotiations and influence the ultimate size of the budget. The secretariat also faces the possibility of a backlash from delegates if the proposal is deemed to be unreasonable. If secretariats have a free hand in crafting this budget, these agents could frame the principals’ debate over the budget level. But the parties have taken steps to curtail this potential area of secretariat influence.

The UNCCD executive secretary’s strategy at COP9 was particularly questionable given that the previous COP had collapsed in the final hours due to the size of the budget. While the strategy did not seem to take the previous budget negotiation process into account, the parties reacted to the secretariat’s perceived overreach by exerting control over future budget proposals. In addition to adopting a budget that was very different from the size proposed by the UNCCD Secretariat, the UNCCD parties at the 2009 COP took a step to take control of the framing of future budget negotiations by placing explicit instructions in the program and budget decision regarding the budget proposals that the secretariat should include in its documentation for the next COP. UNCCD COP9 included the instruction for the secretariat to include budget scenarios reflecting zero nominal growth and zero real growth in the documentation for the next COP (Aguilar et al. Reference Aguilar, Conliffe, Russo, Wagner and Xia2009).

Similar decisions have been taken by the parties to other conventions. For example, the parties to the CBD began requesting specific budget proposals from the CBD executive secretary at COP9, with decision IX/34 requesting the executive secretary to provide three alternatives for the budget.Footnote 5 These alternatives were to include one option based on an assessment of the required rate of growth for the program budget, one option that would maintain the program budget in real terms, and one option that would maintain the program budget in nominal terms. At CBD COP13, the parties reduced the executive secretary’s freedom in assessing the required rate of growth, specifying that it should not exceed 5 percent above the previous biennium in nominal terms.

These decisions have been taken by the parties (principals) to reign in secretariats’ (agents) ambition to frame the program and budget negotiations. In response to secretariats’ efforts to match the proposed budget with the substantive level of activity that the parties’ substantive decisions suggest is necessary, parties have taken steps to frame the discussion as a matter of inflation or limited growth. These examples also demonstrate the contentious nature of the program and budget discussions, with the secretariat pushing for higher levels and the parties focused on limiting the level of growth, often based on percentage amounts rather than the program levels adopted in other decisions.

The parties have been fairly consistent in holding the growth of the core budget and have also taken steps to control the framing of the budget negotiation by instructing the secretariat about the proposals that can be submitted to the COP. The greatest room for variation in funding levels, and possibly for secretariats to access funding for the issues they have introduced, would be through voluntary funding, to which we now turn.

Assessed versus Supplementary Budgets: Space for Ambition?

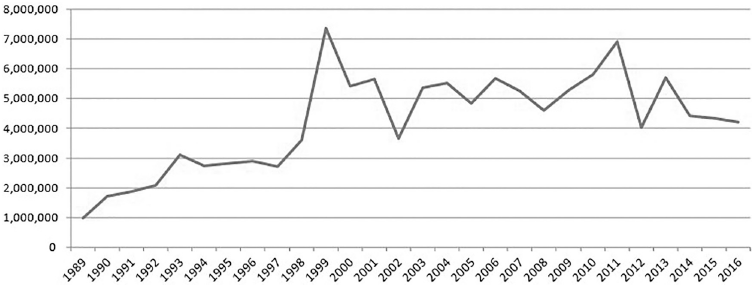

The structure of the budgets for the three Rio Conventions clearly incorporates a division between assessed and voluntary funding and is central to the examination of the relationship between secretariats and member states. Beginning with the first COP for each Rio Convention, the parties have adopted a single operational budget for each convention (referred to here as the core budget). The core budget is based on assessed contributions, using the UN scale of assessments to determine each party’s contribution. Each CBD budget even specifies that the total of this core budget is the “budget to be shared by parties.”Footnote 6 A close examination of the level of assessed funding reveals that it has remained fairly constant throughout the Rio Conventions’ history and is generally aimed at supporting the basic framework of the MEA that the parties established (see Figure 6.1). Earmarked and voluntary funds are directed to the funders’ preferred activities and may therefore focus on projects identified by an entrepreneurial secretariat. However, even these voluntary funds are not always easy to use, even if secured, as parties have instituted constraints on both assessed and voluntary budgets in some budget decisions, often in response to secretariat-initiated efforts. We begin this examination with a focus on parties’ approach to setting the core budget levels for the three Rio Conventions, followed by an overview of the differences between the core and supplementary budgets for the conventions.

Figure 6.1 Rio Conventions’ core budgets plus trust funds

As presented in Figure 6.1, the core budgets of the three Rio Conventions were relatively constant over their first twenty-plus years. Furthermore, the size of the core budgets for the Rio Conventions have been closely and significantly correlated with one another over time (UNFCCC and CBD = .942; UNFCCC and UNCCD = .795; CBD and UNCCD = .714).Footnote 7

Figure 6.1 also illustrates that the adoption of protocols shows up in the supplementary budgets, not the core budget, and does not necessarily result in a lasting increase in the budget. After an initial period at higher levels following the entry into force of the CBD Biosafety and Nagoya Protocols, the CBD budget decreased slightly. The entry into force of the Kyoto Protocol resulted in a lasting higher level of funding for the UNFCCC supplementary budget, although the peak level reached immediately after entry into force was not maintained. The parties have essentially set funding at a maintenance level for the Rio Convention secretariats through the core budgets. Additional activities have required each secretariat to secure specific funding, which implies that the secretariat secured the approval of the funding party but not necessarily the entire COP through negotiated supplementary budget agreements.

A close look at the budgeting structure under the UNFCCC and CBD reveals that parties have sought to exert control by establishing trust funds with specific purposes, although these trust funds still provide vehicles for voluntary and variable funding for new initiatives. For example, with each budget cycle,Footnote 8 the UNFCCC parties have adopted a core budget as well as budgets for the Trust Fund for Participation and the Trust Fund for Supplementary Activities.Footnote 9 The UNFCCC core budget has tripled in size over its first twenty-three years, growing from USD 9,229,700 in 1996 to USD 33,840,957 for 2019.Footnote 10 Meanwhile, the total budgets (core plus trust funds) have grown over five times as large, from USD 13,311,150 in 1996 to USD 67,659,810 for 2019. The funding for ensuring wide participation in the work of the UNFCCC Secretariat dropped between 1996 and 2019, while the funding for supplementary activities has grown. In 1996, the specified cap for the Trust Fund for Participation (USD 2,770,990) exceeded the cap for the Trust Fund for Supplementary Activities (USD 1,310,460). By 2019, although ensuring that all parties are able to participate in the meetings of the COP remains important, the funding for supplementary activities (USD 32,090,651) far exceeded the lowest option listed for the funding for participation (USD 1,728,202).

Among the many activities included in the UNFCCC, the supplementary activities fund has been funding for the Momentum for Change initiative. This example offers an interesting case for how supplementary funding and secretariat initiative can intersect. While this funding is included in the 2016–2017 and 2018–2019 program budgets, the initiative itself began in 2011 at the initiative of the executive secretary and with funding from several foundations (UNFCCC Reference Sollberger2014). The incorporation of this initiative into the supplemental budget means that the parties recognized the value of the project, but it also brings at least a portion of the budget under party constraints going forward.

Unlike the UNFCCC budget, the CBD parties added the Proposed Budget Covered by Voluntary Contributions (equivalent to the UNFCCC’s Trust Fund for Supplementary Activities) during the CBD’s second budget year and the Participation Trust Fund (equivalent to the UNFCCC’s Trust Fund for Participation) during the third budget year. A third trust fund – the Participation Trust Fund for Indigenous Peoples – was added during the CBD’s fifteenth budget year. The establishment of the latter trust fund in itself demonstrates how the principals have exerted control over the agents. The participation funds for indigenous peoples could have been comingled with the existing participation trust fund, but the parties wanted a full accounting for the clearly specified funding purpose. The CBD core budget in 1995 was USD 4,787,000.Footnote 11 It had more than doubled by 2018, growing to USD 12,706,200. By contrast, the total budget was six times as large, growing from USD 4,787,000 in 1995 to USD 31,187,350 in 2018.

As the previous review of how parties frame the budget negotiation suggests, growth in the assessed budgets for the Rio Conventions has been relatively restricted and limited. With the trust funds for participation, parties have funneled funding to principal-endorsed activities. In the case of the CBD, even the background of the participants has been specified, adding further party control to the use of the funds. The supplemental activities trust funds offer the greatest room for new activities and initiatives. This funding source is where we see additional funds coming into secretariats with the addition of new protocols. The supplementary trust funds have also provided a vehicle for moving some initiatives under a party-funded umbrella, as was the case for the Momentum for Change initiative. The next section explores two cases in which secretariats flirted with securing outside funding for unfunded activities, only to have the parties step up their funding commitments in recognition that such funding would reduce their control.

Filling Budget Shortfalls

Because international institutions are vulnerable to budgetary instability, they may need to seek to mobilize “budgetary means from alternative sources in order to reduce their dependence on member state contributions” (Bauer, Knill, and Eckhard Reference Bauer, Knill, Eckhard, Bauer, Knill and Eckhard2017: 187; see also Patz and Goetz Reference Patz, Goetz, Bauer, Knill and Eckhard2017). Our final case studies examine this reaction to instability, in the form of budget shortfalls in two scientific multilateral bodies. These cases provide insights into instances in which secretariats solicited extrabudgetary funding and the response this effort prompted on the part of the parties. In these cases, the principals recognized that their influence would diminish if they were not providing the funding. To understand the shortfalls and options for solutions, we first need to understand these bodies’ funding sources.

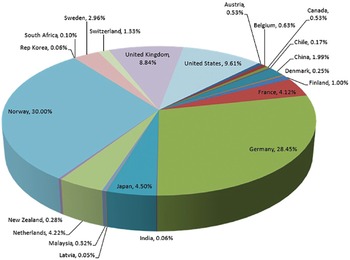

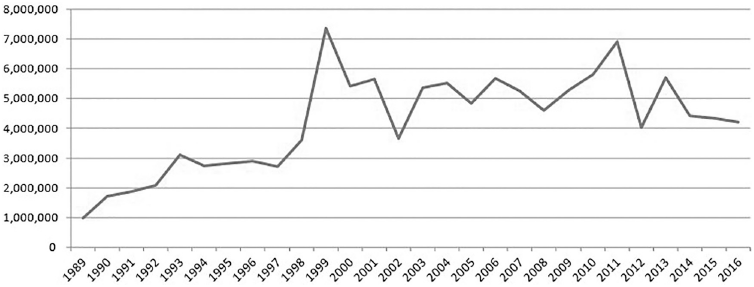

Since its inception in 1988 through 2017, fifty-four governments and organizations have contributed CHF 119,531,971 to the IPCC Trust Fund (IPCC 2017a). Of these, seventeen governments and organizations have contributed 95 percent of the funds: Australia, Canada, Denmark, European Commission, France, Germany, Japan, Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, the United States, the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), UNFCCC, and the World Meteorological Organization. The United States alone, until 2017, had contributed nearly 39 percent of the funds (see Figures 6.2 and 6.3). These figures do not include in-kind contributions, such as support for the IPCC Technical Support Units, publications, translation, meetings, and workshops. In addition to relying on a comparatively small donor base (16 percent of member states), funding varies from year to year. Some funders have contributed only sporadically. Others change the amount they give from year to year – either due to fluctuating exchange rates or their own changing budget priorities (see IPCC 2017b, Annex I, for a complete list).

Figure 6.2 Contributors to the IPCC Trust Fund: 1989–2016

Figure 6.3 IPCC Trust Fund contributions: 1989–2016

IPBES, which was established in 2012, relies on three types of resources: cash contributions to the trust fund; in-kind contributions to support the implementation of the work program; and the leveraging activities of its partners (IPBES 2017a). According to the IPBES Financial Procedures (IPBES 2015), the trust fund is open to voluntary contributions from all sources, including governments, UN bodies, the Global Environment Facility, other intergovernmental organizations, and other stakeholders, such as the private sector and foundations, although the amount of contributions from private sources must not exceed the amount of contributions from public sources in any biennium. The Financial Procedures note that financial or in-kind contributions from governments, the scientific community, other knowledge-holders, and stakeholders will not orient the work of the platform, maintaining the member states as the principals.

As of December 31, 2017, 22 out of 127 member states contributed USD 31,141,874 to the IPBES Trust Fund (IPBES 2017b) (see Figure 6.4). Of these, four governments contributed 77 percent of the funds: Germany, Norway, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Norway and Germany alone have contributed 58 percent. Most of the donors are OECD countries and no international organizations contributed to the trust fund. The amount of contributions to the trust fund generally ranges between USD 3.1 million and USD 4.2 million, with the exception of 2014, which benefited from a USD 8.1 million contribution from Norway at the start of the first work program (see Figure 6.5). The number of donors each year has ranged from thirteen to seventeen, with the exception of 2012, the year IPBES was established. Cash contributions came exclusively from governments. Some donor governments contributed on a regular basis, while others did not, and the amount of each contribution varied (IPBES 2017a).

Figure 6.5 IPBES Trust Fund contributions: 2012–2017

* Does not include pledged amounts not received as of December 31, 2017.

In-kind contributions amounted to an additional USD 2,819,643 from fifteen governments, four intergovernmental organizations, two universities, a graphic design company, and an individual. In-kind contributions are defined as direct support, not received by the trust fund, for activities either scheduled as part of the work program, which otherwise would have to be covered by the trust fund, or organized in support of the work program. In-kind contributions cover a wide range of activities, including: (i) provision of time and expertise at no cost to IPBES by the experts that are members of assessment and other expert groups – an in-kind contribution without which the implementation of the work program of IPBES would not be viable; (ii) costs of participation in IPBES meetings by experts from developed countries that are not eligible for financial support; (iii) provision of technical support for specific deliverables by institutions hosting technical support units; (iv) provision of meeting facilities and logistical support for specific meetings; and (v) provision of data such as data relevant to indicators, access to knowledge otherwise available only for a fee, or free access to existing digital infrastructure (IPBES 2017a).

The IPCC and IPBES have both struggled with funding shortfalls due to the voluntary nature of contributions. Since the early 1990s, the IPCC has sought ways to regularize the budget, increase the donor base, and share the costs more broadly among member states. Year after year, the IPCC Secretariat has sent letters to member states and organizations requesting contributions. Yet, despite best efforts, the funding base did not grow and the contributions continued to vary each year. Substantial contributions by a few member states in the 1990s and early 2000s allowed the IPCC to constitute cash reserves, as expenditures were far below the level of contributions. More recently, however, the reduced contributions as well as number of contributors have decreased the IPCC cash reserves, especially as the level of expenditures has been higher than the income received (IPCC 2017a). As a result, the reserves decreased from CHF 13.4 million in 2010 to CHF 5.8 million in January 2017. While there is no specific requirement as to the size of the reserves in the IPCC Trust Fund, the financial rules provide that a working capital reserve shall be maintained to ensure continuity of operations in the event of a temporary shortfall of cash (IPCC 2017a).

Concern about the ability of the IPCC to complete this assessment cycle led IPCC-45 in Guadalajara, Mexico (March 2017), to establish an Ad Hoc Task Group on Financial Stability (ATG-Finance) with the purpose of exploring avenues for financial stability of the IPCC, including funding options. Also at IPCC-46, the IPCC Financial Task Team reported that the approved IPCC Trust Fund budget – the IPCC fundraising target for 2017 – was CHF 8.3 million. As of January 1, 2017, the opening cash balance in the IPCC Trust Fund was CHF 5.8 million. By June 29, 2017, the total amount of voluntary contributions received equaled only CHF 992,670. A projected funding gap of CHF 5.7 million would exhaust the cash reserves of the IPCC Trust Fund (IPCC 2017a). Hence, there was concern that without more funding the IPCC would not be able to implement its work program which included the special report on 1.5°C and the seventh assessment cycle products.

At roughly the same time, IPBES found itself in a similar financial shortfall. At the fifth meeting of the IPBES Plenary in March 2017, IPBES Executive Secretary Anne Larigauderie presented the budget and draft fundraising strategy. She highlighted that a realistic estimate of current IPBES activities, without launching new assessments and assuming a regular level of national contributions, would require an additional USD 3.4 million for 2017–2019 to complete ongoing activities. The meeting was dominated by discussions on the budget and resulting tensions regarding whether three pending assessments in the platform’s first work program could be initiated and in what order they should be initiated if funds were insufficient for all three. Delegates ultimately adopted a budget that did not allow for the initiation of any pending assessments to reduce the risk of incurring a budget shortfall in 2018 and allowed for the secretariat to proceed in “survival mode” (Jungcurt et al. 2017).

In light of funding shortfalls and reduced budgets, the secretariats for both the IPCC and IPBES and some member states looked for alternative sources of funding. The IPCC and IPBES secretariats, for example, considered options for increasing the contributions from governments, including assessed contributions, in-kind contributions, and broadening the donor base in terms of contributing governments; exploring means to mobilize additional resources, including from UN organizations and others (e.g., UNEP, Global Environment Facility, Green Climate Fund) and evaluating their potential implications, in particular issues related to conflict of interest and legal matters; and providing guidance on the eligibility of potential donors, in particular the private sector. They also explored the viability of contributions from science/research and philanthropic institutions and the option for crowd funding (IPBES 2017a; IPCC 2017a).

Yet when these options were discussed by the IPCC and IPBES plenaries, member states expressed concern that expanding the sources of funding could have repercussions and could decrease their influence on these intergovernmental organizations. For example, philanthropic foundations, in particular, can have enormous influence on political decision-making and agenda-setting in international organizations. This is most obvious, according to Seitz and Martens (2017), in the case of the Gates Foundation, which exerts influence on the United Nations not only through their direct grant-making but also through the placement of foundation staff in decision-making bodies of international organizations, including the World Health Organization (WHO). It further uses matching funds to influence governments’ funding decisions and, thus, priority-setting in the WHO. Similarly, some member states expressed concern about private sector funding that could run the risk of conflict of interest and could damage the panels’ integrity and independence (Mead et al. Reference Jungcurt, Antonich, Louw and Recio2017).

The presentation of these types of funding options to member states led to a clear response. In addition to expressing concerns about conflicts of interest, some member states worried that if the secretariat received funding from a greater number of nongovernmental entities, the principal–agent relationship could erode and the secretariat could become more autonomous from the member states. In response to these concerns, the member states of both panels increased their voluntary contributions. In the second half of 2017, for example, IPCC contributions nearly doubled that of the first half of the year (IPCC 2018). IPBES voluntary contributions from member states also improved (IPBES 2017b).

6.5 Conclusion

The examples reviewed in this chapter demonstrate ways in which program and budget negotiations provide a mechanism through which the principals and agents act and react to influence the direction the institution will take. At the base of the relationship between the parties and secretariat is the fact that principals’ affirmative decision is required at regular intervals to adopt a basic budget and keep the agent up and running. The level of funding for the basic core level of activities has been closely regulated by the principal, with decisions even instructing the secretariat regarding the size of the budget growth that can be proposed for subsequent budgets. This mechanism means principal control in reaction to the agents’ initiatives comes with a time lag, but it also demonstrates the premise of this volume – the principals’ reaction means that agents are seeking ways to exert their influence in the first place.

Additional trust funds in the Rio Conventions have provided room for funding a variety of initiatives, although the parties have maintained a level of control over these funds as well. While provisions are made for secretariats to solicit and secure additional, voluntary, funding, parties have set limits on this funding and have even stepped in when they recognized their control may be impacted if they were not supplying the core budgetary provisions.

Budgetary restrictions can be mechanisms of accountability through which principals limit or direct the activities of their agents. Principal–agent framing for examining the interactions between member states and secretariats in program and budget decision-making reveals ways in which these decisions are used as a mechanism for accountability. This check on the alignment of member state and secretariat priorities and directions is also a function of the structure of the budget, with much of the funding for implementation activities being specifically delineated. The designation of how much the secretariat can allocate from voluntary funds to specific activities – some of which were introduced due to secretariat initiative – adds a layer of control for the principal. The recognition by the principal that it may lose a level of control if it allows the secretariat to solicit outside funds from nongovernmental entities further illustrates how this mechanism plays a role in limiting secretariat influence.

Governments recognize that they have greater control over the organization, its activities, and the budgeting process when they control the budget – either through their contributions or by withholding those contributions. Funding rules specify whether the collective principal holds the primary mechanism of influence and control – the power of the purse – or whether that source of influence and accountability will sit with individual nongovernmental donors (Graham Reference Graham2015). As the member states of the IPCC and IPBES realized, if decisions over funding shift from government donors to private sector donors or other nongovernmental donors, the influence of governments will likely decrease over time and the principal–agent relationship as well as the intergovernmental nature of the organization could come into question. While a decision by the parties to incorporate an activity that began as a secretariat initiative – such as the UNFCCC’s Momentum for Change initiative – could be seen as a sign of secretariat influence over the agenda, it also serves as a mechanism through which the parties can reassert control over the agenda.

Through their decisions on programs and budgets, states continue to assert control over the focus of activity and level of ambition that secretariats can undertake. As these case examples illustrate, many governments are holding onto their position as principals in intergovernmental environmental organizations in order to hold the agent (the secretariats) accountable and regulate secretariat influence while limiting the influence of nongovernmental actors, including the private and civil society sectors. By continuing to wield the power of the purse, governments (principals) will continue to keep these organizations, especially the secretariats, under their control.