Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Miscellaneous Frontmatter

- Table of Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Subjectivities In-Between Early Modern Global Textiles

- Part I Unhomeliness, Mimicry, and Mockery

- Part II The Material Enunciation of Difference

- Part III Identity Effects In-Between the Local and the Global

- Part IV Material Translation and Cultural Appropriation

- Archives, Libraries, and Museums (Abbreviations)

- Select Bibliography

- Index

1 - Subjectivities In-Between Early Modern Global Textiles

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 14 October 2023

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Miscellaneous Frontmatter

- Table of Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Subjectivities In-Between Early Modern Global Textiles

- Part I Unhomeliness, Mimicry, and Mockery

- Part II The Material Enunciation of Difference

- Part III Identity Effects In-Between the Local and the Global

- Part IV Material Translation and Cultural Appropriation

- Archives, Libraries, and Museums (Abbreviations)

- Select Bibliography

- Index

Summary

Abstract

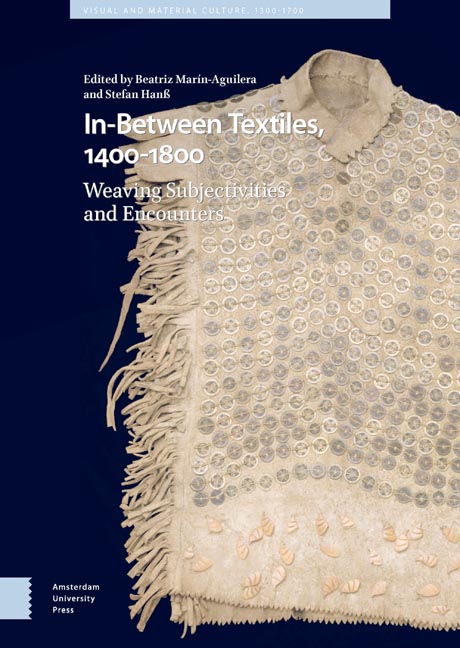

Between 1400 and 1800, intensifying cultural, economic, and colonial connections turned textiles into global artefacts. In a world as globalised as never before, this chapter shows, experiences and strategies of cultural positioning put textiles centre-stage for the negotiation of ever more ambivalent identity politics across the world. This chapter introduces the concept of “in-between textiles,” building upon Homi K. Bhabha’s notion of in-betweenness as the actual material ground of the negotiation of cultural practices and meanings, as well as a site for elaborating material strategies of subjectivity.

Keywords: in-between textiles; postcolonial theory; identity politics; critical material culture studies; Critical Indigenous Studies

Introduction

Between 1400 and 1800, intensifying cultural, economic, and colonial connections turned textiles into global artefacts. One fourteenth-century cloth bore Chinese floral designs, but was woven in Mongol Iran and processed into a clerical vestment in Europe (Fig. 1.1a). In Christian symbolism pelicans were associated with the offering of blood to the bird’s offspring, which evoked associations with the sacrifice of Christ. In European services, therefore, Asian textiles could materialise core principles of faith. From a Mongol perspective, this textile’s transcontinental mobility was imbued with spirituality since “Steppe nomads […] understood circulation as a spiritual necessity. Sharing wealth mollified the spirits of the dead, the sky, and the earth.” At the same time, the sub-arctic trade in furs further channelled the global mobility of Asian artefacts. An eighteenth-century armour made by the Tlingit, Northwest Coast Indigenous Americans, is covered with Chinese coins (Fig. 1.1b).

Little is known about what it meant for European priests to administer the Eucharist wearing Asian textiles, or for Pacific Coast Indigenes to cover their body with metals minted with East Asian signs when going to war. Shimmering metals might have enlivened the light of Christ and Indigenous guardian spirits alike; however, wearing alien textiles also elicited experiences of displacement and dissimilitude. Sixteenth-century European Jesuits active in China consciously started wearing Asian clothing to employ the self-fashioning of Chinese scholars, thereby increasing the success of their proselytising mission in China and the readiness to donate money in Catholic Europe (Fig. 1.2). The Jesuit modo soave, the “gentle” way of conversion, had its ambivalences and perils in a time when cross-dressing was considered to potentially change a person’s sex.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- In-Between Textiles, 1400-1800Weaving Subjectivities and Encounters, pp. 21 - 54Publisher: Amsterdam University PressPrint publication year: 2023