3.1 The Humanitarian Appeal

Research into contemporary philanthropy corroborates the importance of direct solicitations for raising charitable contributions.Footnote 1 How successful relief organisations are in generating capital and gathering resources depends largely on their appeals and fundraising activities. Other beneficial factors for fundraising, such as trust in the organisation or commitment to particular aid schemes, are often also the result of direct appeals or pleas for assistance in documents such as organisation flyers or annual reports.Footnote 2

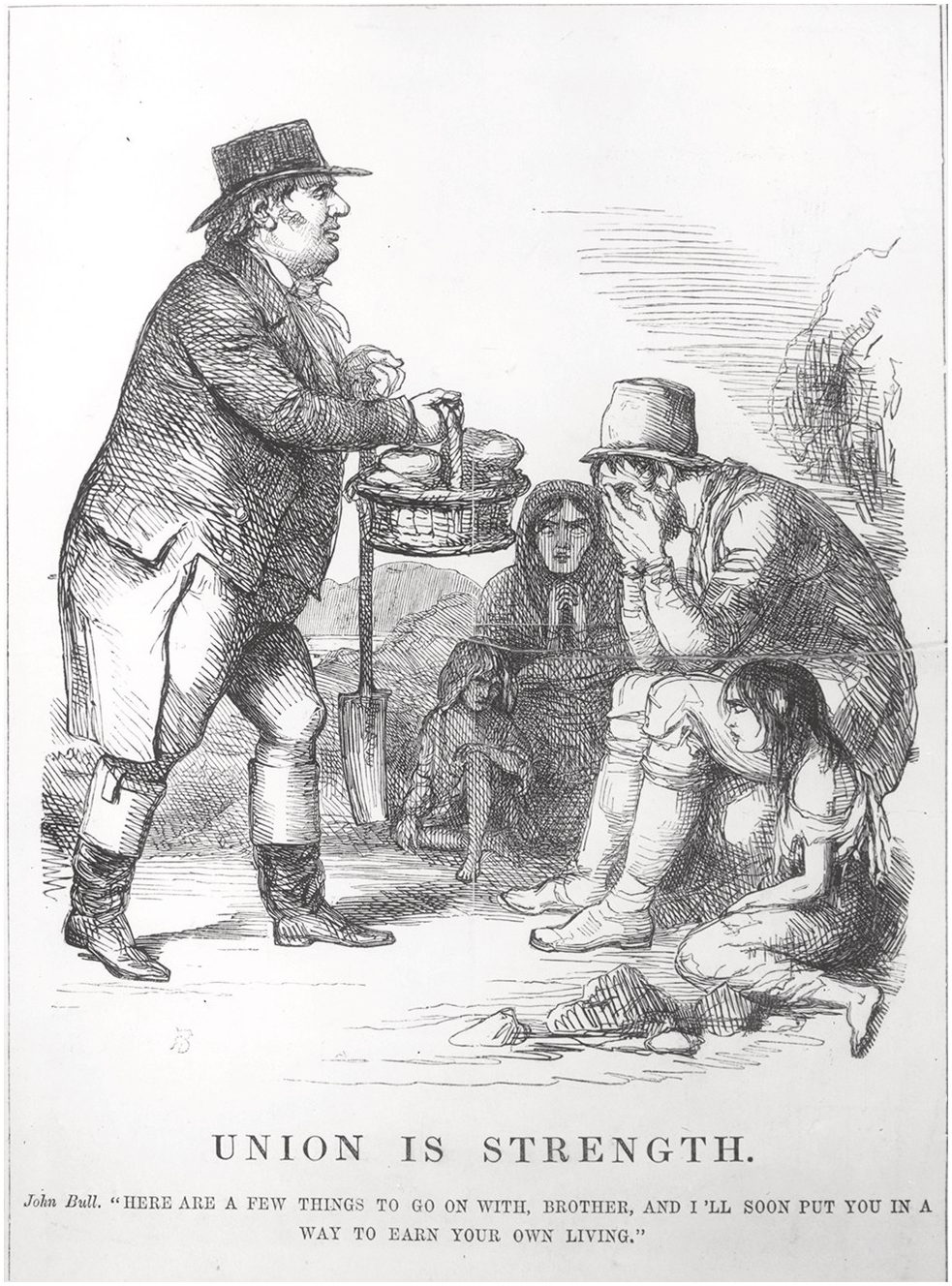

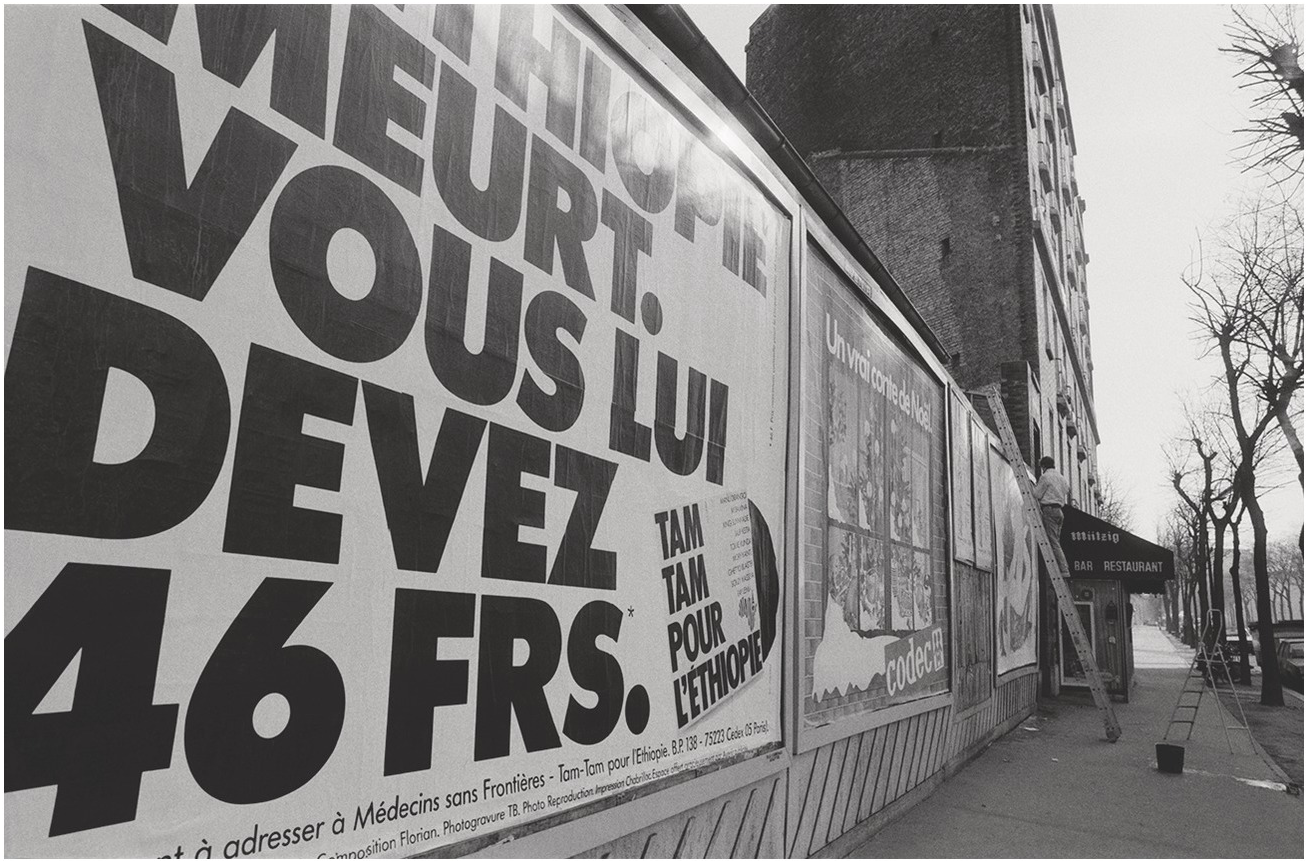

During the representation of needs and agency on behalf of others, humanitarian paradoxes may arise.Footnote 3 Calls for aid try to maximise philanthropic success by narratives and visuals that typically express the moral views of those making the appeal and what they presume may motivate potential donors. On the one hand, humanitarian agents point to need, worthiness, and entitlement, and on the other, they cite compassion, obligation, and interest, thus tailoring their message to different audiences and media formats. Scholars have proposed a variety of classifications for these aid schemes, based on ideal types, general patterns, or genres of appeals.Footnote 4 Analyses tend to overlap with regard to the content and underlying strategy.Footnote 5 Key features of appeals during the last 200 years have been ‘reductivist messages’ and visually based emotional representations.Footnote 6 They use ‘incitement’ (or diagnostic frames), employing facts, definitions, and legitimation of the cause; and ‘enticement’ (or motivational frames), stirring up emotions, marshalling reasons to take action, and evoking images of deserving recipients.Footnote 7

Jeffrey Flynn has proposed two ideal types that may be useful in analysing the moral economy of food aid. The first, which he calls the ‘suffering stranger appeal’, imposes a causal relation on distant suffering by telling donors that they have the means to alleviate misery. The responsibility to help derives here in a Singerian sense from the ability to help. By contrast, the less frequently deployed ‘causal contribution appeal’ confronts donors with their complicity and creates a moral obligation for reparation (rather than aid) by disclosing a causal responsibility for distant suffering. Thus, the former approach motivates ‘those who are capable’, while the latter addresses ‘those who are culpable’.Footnote 8

Irrational Donors and Rational Fundraisers

Economic theories have not been good at explaining why people would make voluntary contributions for the well-being of strangers. The presumption that rational individuals make purposeful choices does not seem to apply to the humanitarian sector. It is an area where individual donors may not actively seek out charitable causes, but do tend to respond to appeals for aid.

Extensive research on donor behaviour shows that the decision to contribute, the amount, the cause, and the organisation chosen are seldom based on rational economic considerations, such as ‘How can one save as many lives as possible with as little money as possible?’. Rather than pondering ideas of effective altruism, donors tend to be influenced by psychological numbing, such as the proportion dominance effect. When asked, people usually say they prefer to save 90 per cent of 1,000 endangered people, rather than 0.1 per cent of 1,000,000 – although 100 more would survive in the latter case.Footnote 9 They also favour actions helping a single individual rather than intervening on behalf of a group, and they prefer a known beneficiary over an anonymous one – the so-called identifiable victim effect.Footnote 10 This effect occurs following minor de-anonymisation and is especially important if the person in need belongs to a potentially adversarial group.Footnote 11

Some patterns are especially evident from an analysis of famine relief. First, it is easier to raise money for sudden emergencies.Footnote 12 The initial days and weeks after the news of a disaster reaches the general public are usually the most successful. However, donations decrease as a relief situation becomes chronic. The amount of publicity given to crises and the donor expectations aroused also shape aid choices of emergency agencies.Footnote 13 Second, the identification of alleged perpetrators and the suspicion that a catastrophe is man-made reduces the willingness of donors to contribute, compared to disasters conceived of as ‘natural’.Footnote 14 It is, therefore, in the interest of humanitarian organisations and their beneficiaries to conceal possible human causes of famine.Footnote 15 Third, research shows that perceived distance correlates negatively with donations. The slogan ‘charity begins at home’ not only expresses parochial or national sentiments regarding who has a greater claim to assistance, but also reflects the widespread expectation that charitable donations will have a greater impact on nearby recipients.Footnote 16 However, humanitarian organisations can counter the latter view by mounting customised appeals.Footnote 17 This is especially important as the willingness to rely on a charitable organisation’s discretion increases with the distance from the population in need; that is, the further away a sufferer is, the greater the acceptance of a humanitarian broker, who otherwise might be deemed unnecessary, to supply aid.Footnote 18 Fourth, there is an in-group effect that prioritises helping members of one’s own social, ethnic, religious, or national group.Footnote 19 Nevertheless, the primacy of the in-group depends on perceptions. Thus, humanitarian organisations may try to create or enlarge in-groups (e.g., children, coreligionists, or people with regional ties), aligning them with the respective cause. In this way, those who formerly were outsiders are admitted to the donor’s in-group through the back door.Footnote 20 By making the self-interest of donors or their in-groups central to a campaign, an organisation can exploit the in-group effect indirectly, even where direct beneficiaries are perceived as outsiders.

As a consequence of these factors, not all disasters result in calls for aid, while other emergencies may result in donations that exceed the basic needs on the ground. Aid supplies depend on funding raised by the effective communication of a humanitarian cause to the public. Ideally, this is done in ways that not only evoke personal emotions, but also result in social concern and a sense of financial obligation.Footnote 21 In order to accomplish such a goal, relief organisations and fundraisers must incorporate strategies identified by research and experience.Footnote 22 Thus, fundraising is an activity that aligns moral and economic rationales: human suffering and the ‘intentions and actions of the donor are commodified’, and the altruistic act of giving is ‘imbued with innovative business models’.Footnote 23 The discrete logic of ‘the good project’, by which aid organisations link donor publics with selected groups of recipients, gains ascendancy, and determines the formatting and merchandising of particular humanitarian causes.Footnote 24 This leads to conflicts within the moral economy. It also entails criticism, as the resulting fundraising practices may collide with changing humanitarian principles, especially idealistic notions of how and where humanitarian work should be done.

Moral Economy Dilemmas

It is a troublesome dilemma that successful fundraising strategies may be ethically problematic and imperil the moral integrity of the organisation and its beneficiaries. The imaginary presented in some humanitarian campaigns, however effective it might be, has been accused of being founded on a ‘pornography of pain’.Footnote 25 The trade-off between emotional appeals with a high financial return and adhering to high moral standards has also been described as a conflict of aesthetics and ethics.Footnote 26 It mirrors the general humanitarian schism between the stereotyped figure of the cold-blooded calculating professional and the compassionate but inefficient grass-roots activist.

Reductionist and paternalistic practices, such as the use of heart-rending images of a woeful child to stimulate compassion, raise the issue of the dignity of would-be beneficiaries upon the conscience of humanitarians who seek to link distressed populations with donors in a manner that is both ethical and efficacious.Footnote 27 While the use of certain essentialising images that contrast with Western plenty may serve the immediate goal of generating donations, it can inhibit the formation of deeper commitments and sustained patterns of collective action.Footnote 28 When celebrities speak on behalf of humanitarian causes, there is a similar risk that they may ‘steal the show’ from those who need help. In this way, some strategies that raise large sums for the most dire situations may hamper long-term change and increase the likelihood that aid will be needed again in the future.

A paradox of the moral economy is that often the most pressing calls for donations are those proclaiming a beneficiary’s entitlement and the obligation of the benefactor to provide aid, factors that appear inconsistent with the voluntarist character of humanitarianism.Footnote 29 Such moral commitment appeals seek to create correlates with the request for government intervention, and therefore entail a measure of charitable self-abrogation. However, the dividing line for the individual donor and public agencies remains that between de facto choice and legal obligation. As long as moral judgement precedes compulsory legislation, the concept of humanitarianism continues to make sense. Michael Walzer has argued that humanitarianism is a ‘two-in-one enterprise’, based on both charity and justice – on the supererogatory kindness that acknowledges a moral duty to strangers.Footnote 30 From the point of view of social psychology, charitable giving resembles the medieval purchase of indulgences, ‘paying taxes to God’.Footnote 31 Today many humanitarian organisations have adopted a vocabulary of justice and entitlements that symbolically empowers beneficiaries.Footnote 32 However, rather than seeking to establish global justice by the redistribution of the necessities of life among the world’s citizens, this practice shows that from their non-governmental perspective, such organisations find utility in drawing on a strong aid narrative.Footnote 33

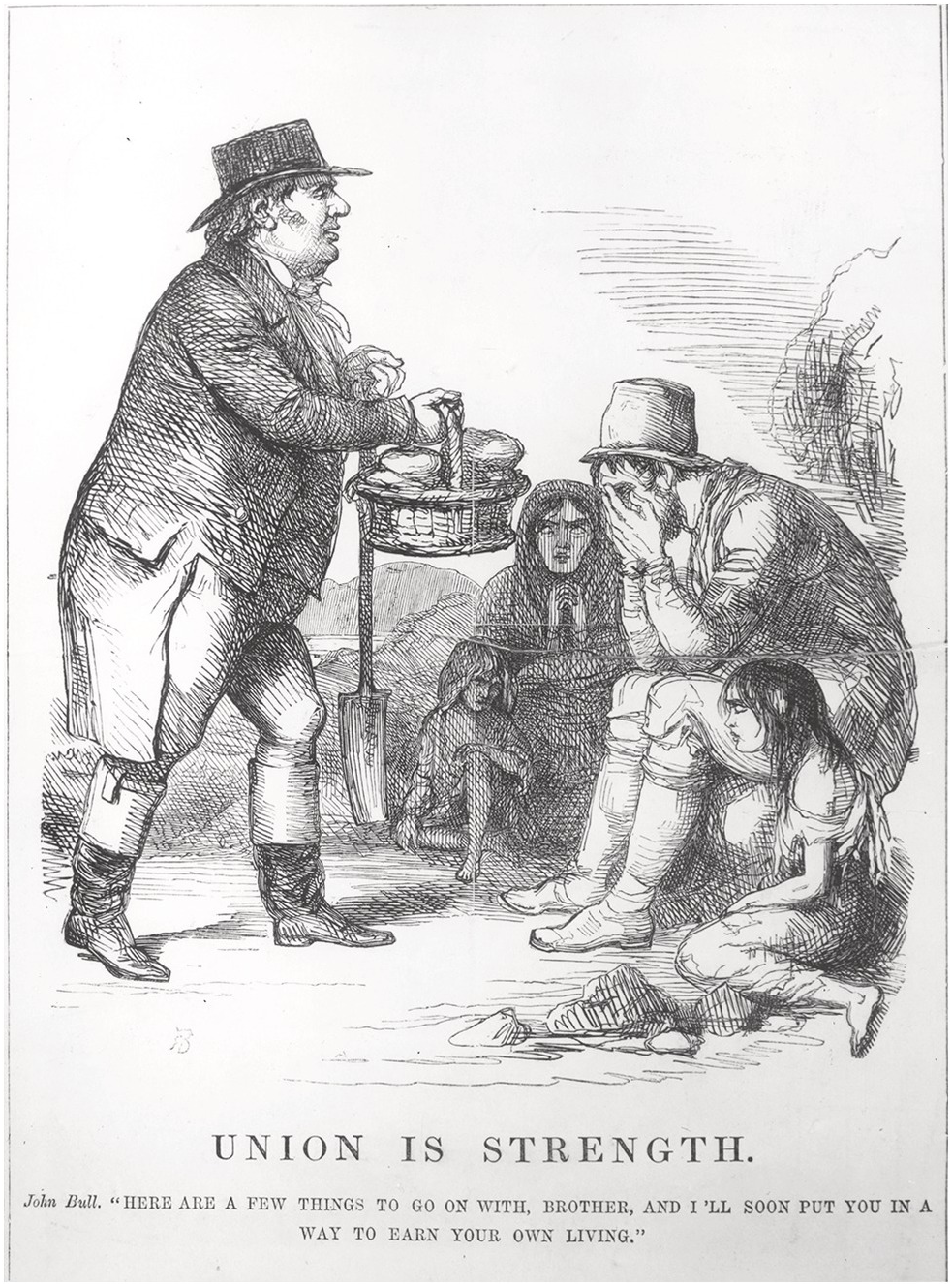

3.2 Empire, Faith, and Kinship: Ireland

In the closing days of 1846, newspapers across England published a Cork magistrate’s eyewitness account of famine in Ireland that was a revelation for the public. The open letter was addressed to the duke of Wellington and described the horror of hundreds of living skeletons in Skibbereen, a small town west of Cork that became notorious for its plight (see Figure 3.1). Even the Times, an organ with little sympathy for Irish suffering and critical towards voluntary contributions, printed the piece in its Christmas Eve edition. The letter included an indirect aid appeal to those who could send relief by urging that ignoring the desperate situation of the Irish would see them fail before ‘the Judge of all the earth’. Moreover, calling upon Wellington to help rescue the land of his birth and not abandon his compatriots who had lost their lives for the empire, the magistrate urged him to bring Ireland’s plight before Queen Victoria and thus secure for himself the inscription ‘Servata Hibernia’ upon his tomb. Wellington was to invoke the queen’s female sense of decency, and let the published letter’s account of destitution and nakedness encourage her to command that aid no longer be withheld.Footnote 34 The letter illustrates that the gendered perception of emergencies and the addressees of calls for aid has not changed over time. Other direct appeals to the queen petitioned her ‘as a woman’ and ‘a mother’.Footnote 35 They all mirrored the widespread notion in Ireland of being entitled to aid from Britain, and minor sums were immediately sent to the Cork magistrate for distribution.Footnote 36 However, according to one Irish calculation, their country was entitled to thirty million pounds, a sum greater than that spent for ending slavery, as Irish distress was said to exceed that of the blacks.Footnote 37

Imperial Relief

The comparatively broad acknowledgement of Irish suffering in the press at the time of the open letter coincided with the preparation of the major extra-governmental aid effort, the creation of the British Relief Association (BRA).Footnote 38 The BRA was a voluntary effort closely related to the government, but its origin and the deliberate exclusion of its beneficiaries from the aid narrative have not been examined. A deputation of the interdenominational Relief Committee of Skibbereen, sent to London in December 1846, took the first initiative, rather than English residents.Footnote 39 The Irish representatives consisted of protestant ministers Richard B. Townsend and Charles Caulfield, who were granted a meeting with the home secretary and with Charles Trevelyan, the permanent secretary of the treasury and the principal figure in government relief to Ireland. At their first meeting, the Irish deputies felt that they were treated as ‘insignificant individuals’; they were then granted a second meeting. Nevertheless, the letter they received a few days later declared that their request for a queen’s letter was premature and suggested the alternative of private Irish, as well as English, charity.Footnote 40

Such a response was not simply an abdication of responsibility: Trevelyan’s evangelical morals, while hostile to state intervention, were more receptive to voluntary efforts. Three days after the first meeting with the deputies, he recommended a general English subscription supervised by officials to supplement what he believed were ‘the necessary deficiencies of our Government Relief’.Footnote 41 Another motivation was the desire to pass the verdict of God and history, despite alleged Irish misbehaviour.Footnote 42 This dutiful attitude is indicative of the widespread contempt for what was perceived as ‘Irish apathy and abuse’. Trevelyan’s belief that ‘further horrifying accounts’ were needed to promote the subscription indicates the dismissive attitude towards reports from Ireland of which there was no lack.Footnote 43 At another meeting, the deputies were made to feel ‘as if they were the first men in the land’ and were advised how to go about raising private charity.Footnote 44

Townsend and Caulfield favoured a public fundraising event that would also rebut English misconceptions about Ireland. Although they were now treated respectfully, they could not obtain the backing of individuals needed for such an undertaking. This outcome was influenced by the deputies’ contact officer, who thwarted their call for support behind their backs.Footnote 45 In their report they state ‘it was by little and little the real nature of our position as a deputation opened upon us’. The contact officer ultimately made it clear that a public meeting was ‘utterly impracticable’, as it was likely to engender political controversy and damage the Irish cause. He promised that the addressees of the deputation ‘would work the matter themselves’ and would raise a subscription far exceeding the expectations of the two representatives. Thus, committing their ‘begging-box into hands most influential at present in the Kingdom’, Townsend and Caulfield returned to Ireland.Footnote 46 The Times explained the deputation’s failure by maintaining that, rather than robbing their own deserving poor and supporting conspiracy, agitation, and possibly arms and secession, the English people preferred ‘to bestow their charity where they can direct its application’ and ‘secure both benefit to the recipient, and something like gratitude to the giver’.Footnote 47

Thus, the London establishment designed its own fundraising campaign. The queen’s offer of £1,000 (an amount equal to that already pledged by several financial magnates) was refused as ‘it wasn’t enough’.Footnote 48 Scotland, where people in some areas were also suffering, was added to the cause in a last-minute manoeuvre to provide a rationale for the queen to double her contribution.Footnote 49 This boosted the legitimacy of the humanitarian enterprise, although, according to a later allotment formula, it implied that one-sixth of the funds collected were diverted from Ireland.Footnote 50 A prominent committee ran the relief effort as an all-British campaign, primarily by means of repeated advertisements in major newspapers and two queen’s letters issued in January and October 1847.

The campaign’s first appeal to the public included a statement on objectives and a list of donors, headed by the queen, and also noted a contribution by the ‘Children and Servants of a Family in the Country’. As customary in nineteenth-century fundraising, accounting elements were prominent through the documentation of subscriptions, but the appeal also indicated restrictions in the appropriation of aid. It was to consist only of provisions, not cash, targeted at individuals with no employable male relative, and was to entail some work by the recipient in return, wherever practicable. The appeal was based on ‘the strong conviction that there are a large number of benevolent persons fully acquainted with the distress, and ready to bestow their bounty whenever a channel is presented to them through which it may be applied, and secured as far as possible from the danger of being abused’. In addition to the BRA’s passive self-image as a strictly controlled channel, it was announced that donors were able to contribute in kind and that earmarking for any particular district would be strictly observed.Footnote 51

Subsequent advertisements were commonly accounting summaries, with indirect appeals in the form of a list of subscribing social peers. The BRA prominently cited the chairman of the East India Company and the governor of the Bank of England as auditors; itemised provisions shipped to various Irish ports; explained the principles of distribution and monitoring procedures; and listed exceptional instances in which small sums of money were granted for further distribution.Footnote 52 Later advertisements included mention of the extreme distress witnessed by agents of the BRA, or limited themselves to printing lists of subscribers and the names of committee members and auditors.Footnote 53 More explicit appeals also continued. In a typical one, the committee expressed its hope that the liberality of the British people would enable them ‘in some degree’ to continue mitigating ‘the horrors of a calamity, the extent and severity of which … it is hardly possible to over-picture’.Footnote 54

Another framework for appeals was provided by a queen’s letter authorising church collections in support of the BRA’s fundraising. It was directed to Anglican bishops in their provinces, thereby prompting them to ‘effectually excite their parishioners to a liberal contribution’.Footnote 55 The letter was read from the pulpit in the first months of 1847, accompanied by sermons promoting the cause of relief. The government also declared 24 March a national day of fasting and ‘humiliation’. A number of sermons were published and raised additional funds by offering arguments to encourage giving. Following the royal proclamation of a national fast day, many ‘famine’ sermons were delivered urging the nation to atone for its collective sins. However, the sense that Ireland, although part of the UK, was a peculiar country suppressed British contributions. The paltry, somewhat hostile response to the queen’s second letter, issued in connection with an improvised national day of thanksgiving, made this especially obvious.Footnote 56

The Irish and English affiliation could be clearly seen in the armed forces. The Irish Relief Fund in Calcutta had been the first attempt of its kind in the British Empire, outside of Ireland itself. At a time of heavy losses in the conquest of India, the fund’s secretary declared that the Irish were those ‘who “clear the road” in the battle’ – that is, comrades-in-arms whose hearts should be comforted by care for their families and friends at home.Footnote 57 A newspaper article cautioned that recent battlefield casualties would mean that fewer remittances would be flowing to Ireland, something that a community effort could mitigate.Footnote 58

At the first public meeting of the fund on 2 January 1846, the Catholic archbishop of Calcutta, despite propaganda for cohesion, took it upon himself to refute the condescending remarks of other committee members by pointing to centuries of English injustice and maladministration that had reduced Ireland ‘habitually to the condition of a pauper’ (see Figure 3.2). He reminded those present that the gospel said donors should make recipients feel that they were receiving charity from ‘equals before God’, and that gratitude was a pre-eminent trait of the Irish character. Apart from addressing bilateral relations, the meeting represented the subscription as an opportunity – in response to the British administration of relief in India – ‘for the wealthy natives of this country to show that they were not behind Europeans in this exercise of beneficence’.Footnote 59 The Calcutta Relief fund continued its work in the following years by sending substantial sums to the BRA and other relief organisations.

The activism in their homeland at the time prompted UK citizens in a number of cities abroad to organise collections among themselves and within the society that they lived in, with varying success. In Hamburg, six individuals called for the support of Europe-at-large for their campaign, suggesting a particular duty was owed to their compatriots, and expressing confidence that the local public would join their effort. The collection raised £450, but a German newspaper derided the call from a different moral economy perspective: ‘Do the wealthy Brits also want to burden us with their country’s destitution? They have instigated it; let them remedy it.’Footnote 60 A charity concert organised in the English church in Hamburg did not attract many people and received a very poor review.Footnote 61 Meanwhile, at a public concert in London, Jenny Lind’s fee for an opera season was said to be £12,000 plus travel and lodging, something that made another German newspaper exclaim with moral economic indignation, ‘And all this, while Ireland starves!’Footnote 62

Catholic Relief

In Catholic circles, Ireland was referred to as the Islands of Saints. It was seen as having provided invaluable historical services to religion, literature, and the advancement of England.Footnote 63 The priest of a Liverpool church, whose background included ties to Ireland, proposed a more aggressive request for relief. He declared that England owed Ireland a great deal for the misery brought about by centuries of tyranny and oppression, and that the Irish had a claim on the gratitude of English Catholics for their successful battle for religious emancipation – something that lifted their coreligionists in the UK up from being ‘a proscribed and degraded class’.Footnote 64 Moreover, Catholic charity was aroused in opposition to what they saw as the ‘black charity’ of the proselytising Special Fund for the Spiritual Exigencies of Ireland. This fund provided relief for those willing to undergo religious conversion, appealing for donations by suggesting that ‘the Gospel is, more readily than heretofore, now received from hands which have willingly administered relief to … temporal necessities’.Footnote 65 In view of its timing in mid-October 1846, the first explicitly Protestant relief activity seems to have come about in reaction to Catholic efforts.Footnote 66

Catholic fundraising in England was generally conciliatory, ecumenical, and careful not to alienate the Protestant majority. At the beginning of October 1846, Irish expatriates in London created a network of district committees for Irish relief that also lobbied the government to compel Irish landlords to be more loyal to their homeland. While the network’s central committee passed all proceeds on to the four archbishops of Ireland, a Catholic magazine emphasised that Protestants, Jews, and Englishmen were among the donors and activists.Footnote 67 Catholic clergymen from Ireland became speakers at fundraising events, such as one held at the City Lecture Theatre in London.Footnote 68 Another preacher from Ireland delivered charity sermons in churches at Leamington Priors and London. Speaking in Christian rather than Catholic terms, he warned that the ‘distressed fellow-creatures in the Sister Country’ might be the ‘future selves’ of his audience, depending on the extent of others’ goodwill. He claimed that charity was ‘blessed in proportion as it blesses’ and that the duty of giving was advocated by nature, reason, and God, the neglect of which would be ‘the forerunner of eternal damnation’. On the Day of Judgement, he declared, benevolent works would insure generous donors ‘a portion of that same mercy which they were that day called upon to exercise towards their famishing fellow-creatures’.Footnote 69 A later newspaper advertisement asked all to ‘remember that Salvation is denied to those who do not feed the Starving according to their ability’.Footnote 70

Around the time that the BRA was set up, Fredric Lucas, editor of the Tablet, in an article entitled ‘The National Christmas Famine’, asked what he and his readers could do about the starvation in Ireland. Being a Quaker convert, Lucas suggested that the Society of Friends had ‘borrowed from the Catholics of other days an example which we ought to be ashamed not to follow’. As he put it, Christ was perishing for want in Irish cabins, and the Catholic code of morality entailed an obligation of charity at the same time that the ‘penalty of hell’ awaited those who failed to perform their appointed task.Footnote 71 From then on, the Tablet became ‘the repository of Irish grievances and of Irish sufferings’ in England – that is, the primary outlet for aid appeals from the Irish clergy.Footnote 72

By the end of 1846, the vicar apostolic (bishop) of London issued a pastoral epistle with instructions for celebrating the jubilee of the commencing papacy of Pius IX. He ordered that an appeal be made in London chapels for the purpose of relieving distress in Ireland as well as in the respective congregation – the collection to be divided into equal portions.Footnote 73 Criticism of the bishop’s coupling of charity abroad and at home made him revise his instructions so that the sum raised was solely devoted to Irish relief.Footnote 74

Episcopal collections were held throughout England and Wales, often on a weekly basis until Easter to enable poor parishioners to contribute greater aggregate sums. One pastoral made it clear that the present Irish suffering ‘has never been equalled in the memory of any one of our generation’, and called for ‘generous sacrifices for its alleviation’.Footnote 75 The bishop of Yorkshire had personally witnessed the distress in Ireland and urged the claims of ‘our famishing Brethren’ upon the charity of his flock, asking rhetorically where those not sufficiently attentive to the cries of the hungry expected to stand ‘on the great accounting day’.Footnote 76 In a subsequent call, he pleaded for additional alms, warning that God was fully capable of afflicting England in the same manner as Ireland.Footnote 77 In a like manner, another bishop’s pastoral cautioned that the time had come ‘for each one to measure out with that measure wherewith he desires that it be meted to him again’. It emphasised that those affected by the famine deserved aid not merely as fellow creatures and subjects of the same empire, but also as parishioners ‘closely knit together with us in religious communion’.Footnote 78

Descriptions of the distress in Skibbereen, and the British home secretary’s letter endorsing private charity in England to the deputies of that town, were reprinted in France and Italy.Footnote 79 As a result, philosopher Antonio Rosmini, an early advocate of ‘social justice’ and founder of the Institute of Charity, was spurred into action. Even before the general British campaign started, he requested one of his missionaries in England to initiate a collection for Irish relief, citing God’s recompensing moral economy. He himself issued an appeal in Northern Italy that raised £556 by the end of 1847.Footnote 80

The first transnational call from a Catholic institution was issued by the Society of St Vincent de Paul (SVP) through its president, Jules Gossin (see Figure 3.3). Upon receipt of various letters and documents from Ireland, the SVP council general had ordered its local branches (conferences) to raise funds for the clients of the ten Irish conferences. The appeal declared that the principle of self-subsistence for local chapters was untenable in view of the extraordinary calamity, and urged the society’s members to give generously and quickly as ‘death does not wait’.Footnote 81 The Dutch national council began its ensuing appeal by reminding members of the Irish saints who had evangelised the Netherlands, suggesting there was a ‘religious debt to pay’.Footnote 82

Figure 3.3 Jules Gossin (1789–1855). Daguerreotype, 1844.

The most authoritative call for Irish relief came from the newly inaugurated Pope Pius IX in his second encyclical, issued on 25 March 1847. Addressing prelates all over the world, he invoked the Catholic tradition of alms-giving for Christians in need, quoting the moral economy of church father St Ambrose: ‘Christians should learn to use money in looking not for their own goods but for Christ’s, so that Christ in turn may look after them.’ Pius IX mentioned his own Irish relief efforts, warned of the worsening calamity, and suggested that Ireland particularly deserved aid for its loyalty to Rome and its missionary engagement around the world. He proclaimed a triduum (three days) of public prayer for suffering Ireland, with an indulgence of seven years granted as a reward for attendees, and exhorted all Catholics to give alms for relief.Footnote 83

A total of 30,000 copies of the encyclical were printed and within a month distributed all over the world by the Sacred Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith.Footnote 84 It was further reproduced by the Catholic press and hierarchy. For example, the Central district (the future Diocese of Birmingham) made 150 copies of the encyclical, which was to be read at all churches together with a pastoral epistle from the bishop.Footnote 85 When it was sent to the Irish bishops, the encyclical was accompanied by a letter that in general terms complied with the wish of Prime Minister Russell that the pope praise the Irish clergy for their conduct during the famine and ask them to trust the government and its relief efforts.Footnote 86

While the encyclical was heeded in many places, it was ignored or depreciated in others. The Austrian emperor, for example, decreed that only the sections on prayer and indulgences be communicated to the faithful, not allowing systematic collections that benefitted foreigners. When the issue was discussed in autumn 1847, the time for relief was considered past, and the extent of American contributions served as a further argument against the need to solicit funds.Footnote 87 In the diocese of Brixen, church collections were made nevertheless, but they were announced incidentally and were only conducted on a voluntary basis.Footnote 88

In St Gallen, a Swiss town named after an Irish monk, where distress in the local bishop’s own parish caused him to leave it to the discretion of the wealthy to contribute to Irish relief, the sum of 4,325 francs (£170) was collected.Footnote 89 The prevailing opinion among Catholics abroad was expressed by a Swiss newspaper, which stated that ‘England has a very heavy – and the primary – duty of Irish relief.’ However, the paper, continued, ‘we may not now ask what duties England has to Ireland, but rather the duties we Catholic Christians from Switzerland must fulfil to aid that unfortunate country’. As in the case of the Dutch, obligations to Ireland were acknowledged for its role in Christianising Germany and Switzerland.Footnote 90

An Irish bishop thanked the pope for his initiative as ‘well calculated to inspire the people with hope and to fill the Clergy with confidence’.Footnote 91 Pius IX had been drawn to the issue of Irish relief when Paul Cullen, rector of the Pontifical Irish College, urged Catholics not to fall behind the generosity of Protestants in Rome.Footnote 92 UK residents of the Holy City held a fundraising meeting on 13 January 1847, at which the rector was represented by a deputy who suggested that ‘the collection [be made] general through the city’; Cullen was also elected to the committee.Footnote 93 It was announced that the pope would contribute 1,000 Scudi (£213), and that he ordered a solemn triduum in one of the local churches from 24 to 26 January, with sermons in Italian, English, and French, to elicit donations for relief. Pius IX expressed ‘the deep pain which it had given him to hear of the suffering state of Ireland’ and ‘regretted that his power of contributing to her relief was not more in proportion to his good wishes’.Footnote 94 Cullen, who was eager that Rome distinguish herself and show the world ‘that she is not only the centre of faith, but also the soul of charity’, explained that the papal donation was ‘a very large sum for one who has so many calls to respond to’ and suggested that a thousand dollars from the pope was ‘more than a hundred thousand from the queen of England’.Footnote 95 In a fundraising pamphlet in the Italian language that appears to have been published on behalf of the Rome committee of UK citizens, Cullen claimed it was general knowledge that the English government had failed to provide sufficient relief.Footnote 96 He later described the underlying significance of the pope’s encyclical as ‘a standing testimony against the misrule of England’.Footnote 97 A contemporary witness commended Cullen’s sermon during the triduum as impressive.Footnote 98

Acclaimed pulpit orator Gioacchino Ventura held the triduum’s main sermon in Italian. He suggested that the spirit of charity was the bond uniting all Catholics, but that the Irish people also had particular merits, had suffered extraordinarily, and had conducted themselves admirably, making them deserving of his audience’s best sympathies. Hence, he

conjured all his hearers in the name of humanity, virtue, love of country, and above all of religion, to aid by their contributions, and by their most fervent prayers to rescue from starvation a people, which was a model to all the countries in the world, for their social virtues, their patriotism, their fidelity to constituted authority, and above all for their attachment to the Catholic Faith, their practice of its holy duties, and their zeal in propagating it.Footnote 99

Ventura framed the welcome contributions by English and Irish Protestants in Rome as ‘an emanation of Catholic charity’, inherited from the spirit of their forefathers or inspired by the surrounding Catholic atmosphere. He hoped that what appeared to be Irish acquiesce in starving to death in union with the disposition of Christ would ‘ascend as a holocaust of reconciliation to the throne of the Most High, to draw down on England not the justice and indignation which liar crimes deserve, but conversion to the true faith, grace, mercy, and salvation’. The colourful report on the effects of the sermon, with its surrounding choreography of church rituals for a time of famine and an appeal by alumni of the Pontefical Irish College, included the observation that ‘the very beggars with tears in their eyes emptied the contents of their poor purses into the hands of the collectors’.Footnote 100

Rome’s example was followed in some Italian bishoprics even before the pope’s encyclical was issued. Thus, a pastoral letter from the town of Jesi argued that Christian charity being universal, the obligation towards brothers of faith was all the more stringent; that the modern principle of association was a force for good; and that the rational and enlightened spirit embodied in public opinion contributed to the denouncement of selfish behaviour. The Jesi pastoral underscored the possibility that the local populace might some day find themselves in need of such aid, and so charity shown to Ireland might be insurance against such a calamity befalling their own selves. It also claimed that God rewarded ‘good works with great interest, giving eternal glory as the recompense of the most trifling acts of beneficence’.Footnote 101

Apart from church collections, committees in Rome and Florence launched fundraising events such as society balls and an aid concert. One socially conscious woman even organised a lottery for a valuable painting.Footnote 102 The pope himself provided an autograph letter and a rosary of agates that were exhibited at a bank in London and raffled off for the relief of Irish famine hungry. However, the £61 realised fell short of the £100 that the organisers had hoped for, and critics accused the event of ‘dispensing the spiritual graces, of which the Pope claims to be the depositary’.Footnote 103

The idea of famine relief as an undertaking for the entire Catholic world originated with Gossin at a point in time before the SVP’s general appeal, and the Holy See acknowledged the SVP’s role in bringing the encyclical about.Footnote 104 Gossin was the driving force behind a petition signed by 197 prominent Frenchmen, including mathematician Augustin-Louis Cauchy, publisher and politician Count Charles de Montalembert, and political analyst Alexis de Tocqueville. Dated 6 January 1847, it called on the pope to launch a ‘new crusade, although a completely peaceful crusade, a crusade of charity, of prayer, and of good deeds’ for suffering Ireland and for persecuted Christians of the Lebanon as well. By May, when the archbishop of Paris implemented the famine encyclical, a subscription was opened under his auspices.Footnote 105 The committee’s public appeal described it as ‘a truly national and French enterprise’ that would attract everyone, without distinction of party or creed. The appeal stated that high food prices were responsible for the campaign’s slow start, but insisted that French economic hardship could not compare with the suffering of the Irish.Footnote 106 However, the minister of justice protested against unauthorised publication of the encyclical and reminded the French clergy of the requirement of obtaining permission to do so.Footnote 107

The bishop of Marseilles had already issued a pastoral epistle on 24 February that drew an analogy between the Irish and the early Christians, who, during the Roman Empire, adhered to their faith even under torture. He also argued that Catholic beneficence was particularly called for in light of the active proselytism in Ireland; and, as in the pastoral from Jesi, he suggested that a universal plea for charity was even more incumbent on his coreligionists when those who were suffering belonged to ‘the great Catholic family’.Footnote 108 Following the encyclical, at least twenty-one French bishops published pastoral letters. Despite differences in form and content, their message was one: ‘The Irish are starving and need your help.’ An analysis sees a deliberate choice of shocking examples, but also notes the ‘almost throwaway fashion’ in which the famine is presented. The arguments put forward were similar to those of English and Italian clerics, but some French pastorals also suggested that famine relief offered a high moral ground vis-à-vis the English, or that it otherwise served the self-image of France as le grande nation.Footnote 109

Despite the fact that French collections for Ireland were generally church organised, they were ultimately coordinated by the voluntary Comité de secours pour l’Irlande. Laymen took a prominent role in the effort because of the contemporary distress prevailing in France. It was regarded as ‘a matter of Prudence not to expose the clergy to be reproached by the people of neglecting their fellow Country men, and of manifesting their solicitude for strangers’.Footnote 110 However, the Irish were no strangers to the French Catholic elite – they were their idealised model of Catholic spirituality.Footnote 111

US Relief

Catholic appeals in the New World resembled those of the Old, but at times had clearer political references and more compelling language. For example, John Bernard Fitzpatrick, bishop of Boston, stated in a pastoral that Ireland no longer lamented her lost liberties nor the union with Great Britain, bewailing instead the dying of her children. According to him, ‘our own home; or at least … the home of our loved fathers and friends’ required extraordinary charity, something that made any discussion of responsibilities of the UK parliament or Irish landlords immaterial. This engendered the bishop’s conviction that ‘not one will fail to act nobly and generously his part, or to fulfil to the extent of his means what we do not hesitate to call a sacred duty’.Footnote 112

Irish communities were the driving force for famine relief in North America. In addition to Catholics, those communities included Protestants and had much to gain by reaching out to a wider public. The resulting fundraising rhetoric outlined an impartial, national campaign that resembled the one in France. North American society, however, was more diverse. It was made up of large groups of Irish immigrants with a vested interest in their country of origin, alongside a Protestant majority with no particular religious affinity to Ireland. The situation in Canada was akin to that of the USA, but contained a stronger Catholic element and had the British Empire as an additional bond. Nonetheless, a satirical journal in Montreal derided the Irish predominance in relief committees by publishing a fictional list of miniscule contributions, all coming from members of one family clan.Footnote 113

It has hitherto been accepted that Irish relief was a national US effort, without scrutinising who was involved. It has not been considered that downplaying social disparities between donors is a common humanitarian propaganda strategy, although the emphasis on particularly deserving beneficiaries frequently surfaces amid an overall universalist rhetoric. For example, a speech that Henry Clay delivered at a New Orleans town meeting in 1847 invoked a humanitarian imperative irrespective of colour, religion, and civilisation. After a tribute to universalism, Clay explained at length that the meeting did not concern any distant country, but a nation ‘which is so identified with our own, as to be almost part and parcel of ours, bone of our bone and flesh of our flesh’.Footnote 114

President Polk’s threat to veto US government aid to Ireland for constitutional reasons thwarted a plan that had been developed with reference to Americans being an ‘offspring’ of the Irish.Footnote 115 However, civil society responded positively to a convention in Washington on 9 February 1847, chaired by Polk’s vice-president. A member of Congress from each of the twenty-nine states was appointed an honorary vice-president of the meeting, which recommended that fundraising committees be set up throughout the USA. A lengthy appeal was issued to the public, cautiously mentioning that there were hundreds of famine victims, explaining the hardships in Europe, and the efforts made by the British. The Cork magistrate’s letter to Wellington was cited, as well as correspondence from the West Cork region addressed to the ‘Ladies of America’.

Although the Washington appeal spoke of ‘a sister nation’ to which one of the speakers suggested the USA owed ‘a deep debt of gratitude’, and which according to another was well blended into the American ‘blood’, the overall approach and message were universal. Robert Dale Owen, congressman and son of the British social reformer, exemplifies this with an appeal that anticipated Singer’s argument on the insignificance of distance whenever there is knowledge of need. Other voices suggested that the financial boom in the USA at the time (which was in stark contrast to bad harvests and economic depression across Europe), and the demand for labour and settlers, facilitated the framing of Irish relief as a broader cause. The meeting concluded with the adoption of a resolution moved by an Irishman, thanking those involved in the gathering and, by extension, the American nation, and indicating an elaborate humanitarian choreography.Footnote 116

Despite the advancement of famine relief as a national cause, the case of the Philadelphia Irish Relief Committee, which, according to a recent study, typified ‘“universal America” where class, ethnicity, and religious denomination did not matter’,Footnote 117 indicates the need for critical review. The first relief committee in November 1846 was practically an organ of the Hibernian Society for the Relief of Emigrants from Ireland, although it figured as a group of ‘gentlemen’ who addressed ‘fellow citizens’ in Philadelphia and the south-western region of the USA. By February 1847, in order to extend its reach beyond the ethnic ghetto in more than words, the committee broadened its membership. However, the majority of members of the executive committee for the city of Philadelphia still belonged to the Hibernian Society. Others bore Irish names. Yet another called attention to ‘the claim of the Irish people upon us, from blood association, and the influence of the many domestic ties’. The committee resolved that its papers be placed in charge of the Hibernian Society and, in its final report, noted that its relief efforts had not been confined to people of Irish descent – a truism that downplayed the centrality of the ethnic community in the campaign.Footnote 118

The Philadelphia Committee, with its published report and the extensive documentation of its networking within the city’s Irish community’s elite, is easily verifiable with regard to its social basis. It suggests that the case of the similarly named Irish Relief Committee, which was organised by the Hibernian Society of Charleston, was not the exception researchers have claimed, but may rather have been typical of relief initiatives for Ireland.Footnote 119

The first foreign effort mounted in the USA to assist Ireland was initiated by John W. James, the president of the Boston Repeal Association, on 25 November 1845. He proposed a subscription among members of the organisation ‘for their suffering brethren, which would, when sent forward, not only do much to relieve their distress, but also redound to their own credit’.Footnote 120 The resulting Irish ‘community effort’ was based on collections in churches, at a public meeting, and private subscriptions. However, since it was linked to the movement for the repeal of the Act of Union between Great Britain and Ireland, this aid effort and its association with the demand for Irish autonomy came into conflict with political priorities.Footnote 121 In the years that followed, the Boston Repeal Association continued to collect funds for Ireland, but it combined providing food aid and the shipment of arms for the insurgency of ‘Young Ireland’.Footnote 122 The repeal movement had branches throughout the USA that it also mobilised for famine relief in other areas.Footnote 123

By 7 February 1847, after the Catholic clergy of Boston had established a committee that became the Relief Association for Ireland, a broad circle of sponsors from that city disseminated an address on Irish relief by means of the newly introduced electric telegraph. It reportedly made a strong impression on the country.Footnote 124 Various calls led to the formation of the broader New England Relief Committee one week later. The appeals urged the public to provide relief regardless of the causes of famine. They emphasised suspicions that the reports from Ireland may have been exaggerated were untrue.Footnote 125 During a time of US aggression against Mexico, a Protestant minister declared that the sight of relief ships ‘under the white flag of peace and mercy’ would be a ‘nobler spectacle’ than that of battleships, and said that aiding Ireland would make war with the UK psychologically unlikely.Footnote 126 An examination of contemporary speech acts shows that they highlighted notions of Christian duty, idealistic humanitarianism (sometimes from an internationalist perspective), and a belief in the obligation of sharing America’s abundance. Some voiced uneasiness over profitting from the European food shortage or the Mexican War, seeing an opportunity to improve British–American relations. An instance of Irish aid for New England in the seventeenth century was recalled. As in the case of other US relief efforts, it appears that the sense of common purpose that was evoked had a value of its own for a much divided community.Footnote 127 At the same time, the strong Irish presence in Boston, despite being poorly integrated, was a significant factor. A major facilitator of the Boston civic effort was of the opinion that the Great Irish Famine represented a unique charitable cause because its stories came ‘so directly from the Irish around us, who themselves contributed all they could to relieve their relations in the old country’.Footnote 128

In New York, where people of Irish descent made up a quarter of the population, the first Irish relief committee was formed in December 1846, mostly by members of the ethnic community with affinities to the Democratic party. A broader General Relief Committee coalesced by February 1847. It included, among others of Irish background, the Quaker Jacob Harvey, who conducted public relations that raised famine awareness throughout the USA and resulted in funds that were generally forwarded to the Society of Friends in Dublin. The Irish-born Catholic bishop of New York joined forces with the general committee, serving as a speaker and, in an ecumenical gesture, transferring the collections from his diocese to the Society of Friends as well. Despite a considerable Irish presence among the committee members, its founder and chairman, Myndert van Schaick, did not have a family connection to Ireland. Ultimately, the committee represented a broad group of businessmen and prominent individuals with links to shipping interests and to the Commissioners of Emigration (i.e., immigration) of the State of New York.Footnote 129

During the 1840s, a period of rising food prices and mounting freight rates, the transportation of emigrants was a business that lowered the overall cost of conveying American goods to European markets. One of the most active members of the New York committee was the treasurer of the Irish Emigrant Society of that city. Harvey, who was among the commissioners of emigration, envisioned a solution to the Irish subsistence crisis through populating the American West: ‘The more people we can bring over, the better for all parties.’Footnote 130 Van Schaick concluded a public speech somewhat obscurely with the hope that ‘the Irish people would adopt the American system of Common School education, or something similar to it, which would enable them to take care of themselves in future’.Footnote 131 The committee’s appeal to the public distilled the economic fundamentals down to a single line ‘What is death to Ireland is but augmented fortune to America; and we are actually fattening on the starvation of another people.’ The appeal raised the cry that four million people were on the verge of starvation resulting from a famine that was not caused by improvidence or vice. A triad of charity, civilisation, and Christianity was invoked, along with the plea that ‘Every dollar that you give, may save a human being from starvation!’Footnote 132

US celebrity peace crusader Elihu Burritt made a similar appeal in one of his ‘Olive Leaf’ broadsheets to the American people. Reprinted by US newspapers, it claimed that ‘A penny a day will save a human life.’ (For his audience at home, he translated the phrase as ‘two cents’ worth of Indian meal’.)Footnote 133 Burritt also travelled to the scenes of misery, reporting on what he found in another ‘Olive Leaf’ that circulated across the USA and England.Footnote 134 He described people in the terminal stages of starvation, and added political observations comparing the dire labour situation in Ireland with ‘the curse of slavery’.Footnote 135 For his British audience, he published a pamphlet detailing three days of horror he experienced in Skibbereen in February 1847. A prominent Quaker wrote the pamphlet’s foreword and called for a moral economy for Ireland equivalent to that of England. He based his appeal on the Irish people’s entitlement to ‘support from the land and other fixed property’ which entitlement, in times of distress, superseded any landlord’s or creditor’s demand for rent or interest.Footnote 136 However, he did not go so far as to suggest that there was a moral economy that included Ireland as an equal among the other members of the UK.

3.3 Altruism, Self-interest, and Solidarity: Soviet Russia

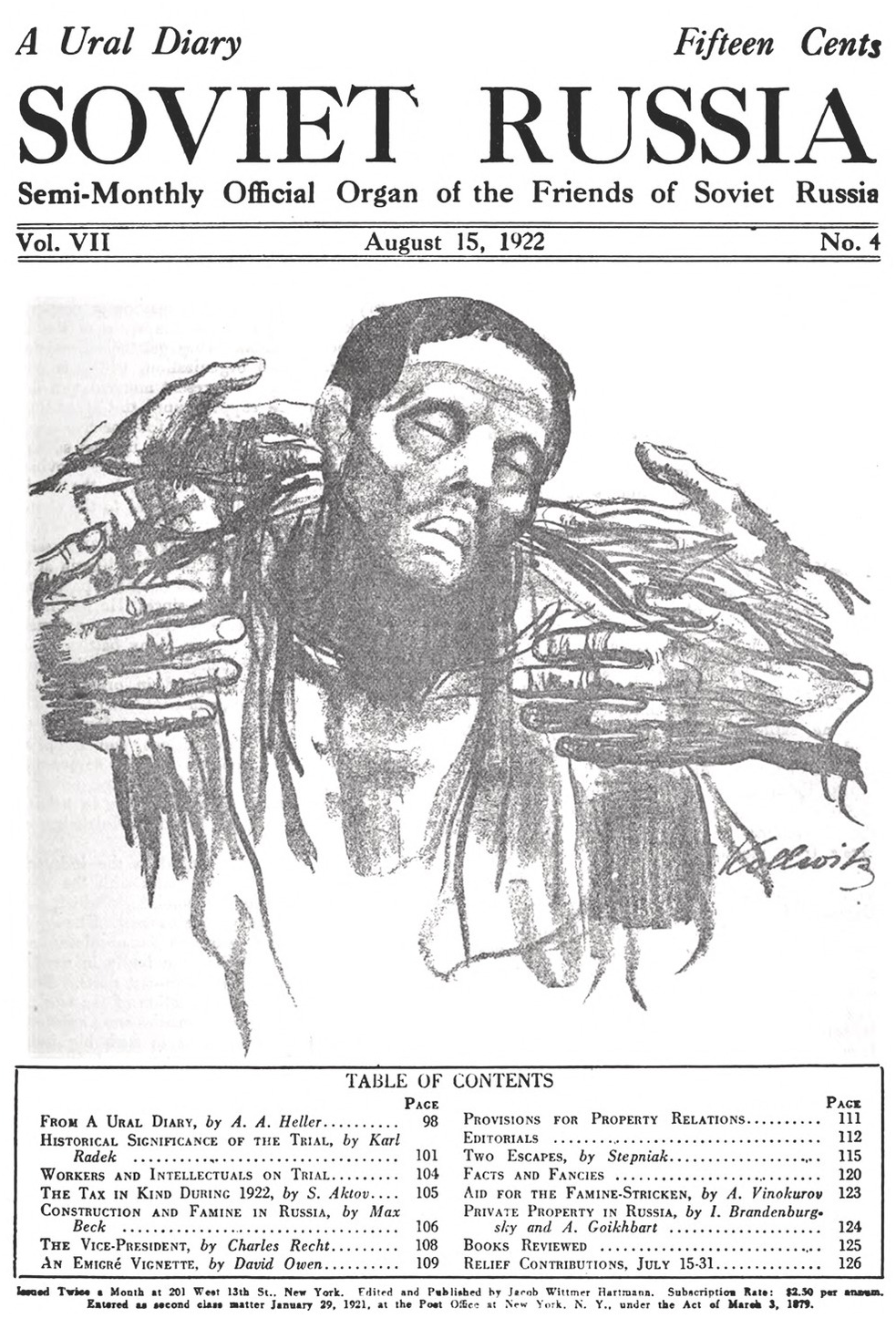

Although it was known for months that a famine threatened parts of Soviet Russia in 1921, it was Maxim Gorky’s appeal in July of that year that first brought the famine to the world’s attention. In contrast to many other famines, relief was triggered by a representative of the afflicted country requesting help for himself and his compatriots. It was a ‘deputy appeal’ in the sense that Gorky lent his voice to the Bolshevik government, which after long reluctance had decided to accept foreign aid. To make the call more acceptable to the West (and perhaps also to avoid humiliation), the Russian leadership signalled their ‘surrender’ through a non-communist international celebrity. Lenin and the People’s Commissar for Foreign Affairs, Chicherin, only launched their own, somewhat different, appeals weeks later. Accordingly, Gorky did not speak in the name of the government, but rather for the Russian people. Stressing their cultural significance, he wrote ‘Gloomy days have come for the country of Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky, Meneleyev, Pavlov, Mussergsky, Glinka and other world-prized men and I venture to trust that the cultured European and American people, understanding the tragedy of the Russian people, will immediately succor with bread and medicines.’Footnote 137

While initially stating that the famine was caused by nature, thereby relieving the government of responsibility, Gorky also blamed ‘the damnable war and its victors’ vengeance’ for the conditions, thus suggesting an unsettled debt on the side of the West. Gorky developed this thought further by demanding aid especially from ‘those who, during the ignominious war, so passionately preached fratricidal hatred’, although he did not point to a specific country or group. Finally, when he characterised the famine to Western philanthropists as a ‘splendid opportunity to demonstrate the vitality of humanitarianism’, it was with a tinge of sarcasm, although he apologised immediately for his ‘involuntary bitterness’. He concluded by asking ‘all honest European and American people for prompt aid to the Russian people’.

During the following months, Gorky’s appeal was reprinted in newspapers abroad and used in the campaigns of various relief organisations. It was the starting point of an international relief campaign. For example, while the Save the Children Fund (SCF) magazine The Record had barely mentioned conditions in Russia until then, the famine dominated its headlines and those of other relief organisations’ publications, such as the Bulletin of the American Relief Administration (ARA), for the next one and a half years. Dozens of smaller aid agencies, committees, and individuals, along with journalists, did their best to keep the Russian famine in the public eye.

Funding Approaches

After the ARA and Nansen’s International Committee for Russian Relief (ICRR) had signed treaties with the Soviet government, their affiliated organisations promulgated appeals in a multitude of leaflets, letters, and newspaper advertisements. There was some cooperation among them, such as the All-British Appeal, but often they competed for donations. The SCF addressed people from all walks of life through advertisements placed in mass media, whereas other organisations focused on specific groups. Thus, the Joint Distribution Committee (JDC) called upon American Jews, the Volga Relief Society (VRS) solicited Americans of Russian-German origin, the Berlin-based Workers’ Relief International (WIR) and their US auxiliary, the Friends of Soviet Russia (FSR), appealed to the working class, and religious groups solicited their own members. In addition, a great number of individuals founded voluntary committees that collected donations from acquaintances or colleagues.

The ARA, as a US umbrella organisation, never made any public appeals. Before the Riga treaties were signed, Hoover was already determined to oppose appealing to the public, as had been done in relief work for Central Europe in 1920.Footnote 138 He was convinced that US citizens should not be asked for help again, as their charitable generosity was exhausted. The slogan ‘charity begins at home’ gained momentum, especially as relief for ‘Red Russia’ was the object.Footnote 139 As an ARA staff member put it, Hoover ‘has dreaded seeking, or encouraging others to seek, financial support for people outside our own country during a period when so many of our own people are unemployed’.Footnote 140 Another reason for the ARA not launching a public appeal was to avoid discussions and counter claims that they feared might endanger the whole operation.Footnote 141

These considerations were paralleled by doubts concerning the profitability and practicality of public appeals.Footnote 142 In contrast to other organisations, the ARA aimed to fight the famine in its entirety. From the start, Hoover was certain that the Russian operation was ‘entirely beyond the resources of all the available private charity’ and needed substantial governmental support.Footnote 143 He considered it a better strategy to ask Congress for a larger sum than to hope for thousands of small donations. However, while rejecting a public appeal, the ARA turned to long-standing supporters and primarily solicited their major donors.Footnote 144 The ARA also established its own press department, which supplied journalists in the USA and correspondents in Russia with press material, instead of paying for advertisments.Footnote 145

The fundraising campaigns of organisations affiliated with the ARA felt the impact of this strategy.Footnote 146 After Congress had granted US$20 million to the ARA, other relief organisations were asked why the public was still being appealed to for donations, and whether the government contribution would not be ‘sufficient for the necessary work’.Footnote 147 For smaller organisations that did not receive governmental funding, the crowding out tendency of public funding and Hoover’s reservations posed a serious problem.Footnote 148 Hoover had not only refused to back an appeal, but at the turn of 1921/2, publicly announced that there was hardly any need for additional grain donations, as the Russian infrastructure could not cope with more than the ARA was already supplying. Some Quakers regarded this as conscious sabotage, and the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) sought to make Hoover retract his statement.Footnote 149

Morally Worthy Recipients

Advocating and justifying relief for the population of a foreign country was far from uncontroversial after the Great War, but in the case of Russia, nearly all organisations (apart from some pro-communist groups) faced an even greater challenge: raising money for a foreign power with a hostile ideology. After all, during the Russian civil war, most Western states had openly supported the Whites in their fight against the Reds.Footnote 150 Many saw communism not merely as an alternative political system, but as a disease spreading chaos and threatening civilisation, especially as Western media had provided their readers with sensationalistic stories about Bolshevik horrors.Footnote 151

Many politicians, some members of the press, and Russian emigrant organisations criticised relief efforts as aiding the Soviet government.Footnote 152 In order to create ‘morally worthy victims’, aid organisations tried to draw a distinction between Russian citizens and the Bolshevik government.Footnote 153 They had to ‘make people realise that these Russian children, starving and dying, are essentially the same as our own’, as The Record put it.Footnote 154 Accordingly, ordinary Russians were portrayed as ‘brave, simple, splendid folk’ who carried out relief work as best they could and were no Bolsheviks.Footnote 155 Hoover himself stated on several occasions that the Russian people could not be blamed, nor should they suffer, for the mistakes of their government.Footnote 156

However, even if those starving were Bolsheviks, many humanitarians were convinced that political considerations must not play a role in alleviating a famine. Nansen rhetorically asked his critics whether it would be worth letting twenty million people starve to death in order to avoid strengthening the Soviet regime.Footnote 157 SCF co-founder Jebb even admitted that relief tended to benefit the Soviet government because the ‘indirect result of relief is to … stabilise the existing order’, but like Nansen she asked whether this would be reason enough to let millions of Russian children die.Footnote 158 An article in The Record at the time argued that ‘it is a detestable and frigid charity that refuses to stretch out a hand to save those who differ in politics or religion from itself’. Nevertheless, the criticism had an effect, and many appeals concentrated initially on the least controversial group, Russian children. As the article stated, those children are ‘no more Bolshevik than you and I are’.Footnote 159 Both the SCF and the ARA kept emphasising that all food would reach the children, that no Red Army soldier would profit thereby, and that those on the ground providing relief would immediately leave the country if the smallest part of the aid was diverted from the children.Footnote 160

In addition, relief organisations, except for communist ones, largely avoided speculation about the causes of the famine. If reasons for the famine were discussed at all, it was described as a natural catastrophe that came to the Russian people ‘not through their fault or the fault of others’.Footnote 161 Possible human factors, such as Soviet policies or the blockade imposed by the Western Powers, were brushed aside to avoid controversy.Footnote 162 In one of the few cases where the question of guilt was mentioned in The Record, the author tried to create a balanced picture in which both sides were to blame:

While it may be true that misgovernment has aggravated the effects of the famine, it must be remembered that it is primarily due to the war, the blockade and the drought of last year, for which the Russian people are in no way responsible, and in any case this furnishes no ground for allowing the population to die while we carefully apportion the blame for their death.Footnote 163

This narrative absolving the Russian government of blame was necessary as co-operation with Russian authorities was essential for relief work to succeed. In order to describe the Russians – even communists – as deserving beneficiaries, Russian institutions were praised for their willingness to co-operate and conflicts were downplayed. In addition, it was underlined that the Russians had not passively submitted to their fate, but that the government and the population heroically fought the famine. ARA, SCF, the Quakers, and especially the WIR emphasised Russian relief efforts and their co-operative spirit in articles and appeals. Well-organised children’s hospitals, the exemplary work of Russian volunteers and employees, domestic fundraising efforts, the distribution of crop seeds by the government, and similar Russian initiatives were highlighted to Western audiences.Footnote 164 Internally, however, criticisms about the lack of Russian assistance, their inadequate work ethic, and a cumbersome bureaucracy were widespread, especially within the ARA.Footnote 165

Mixed Emotions: Children, Horrors, and Holidays

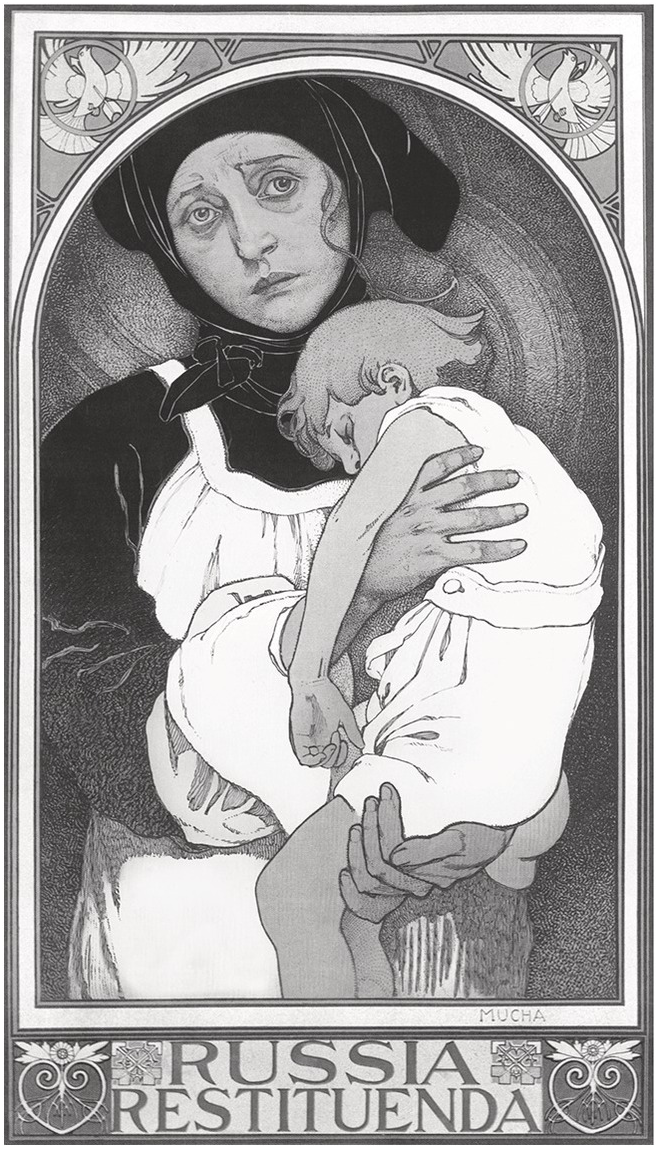

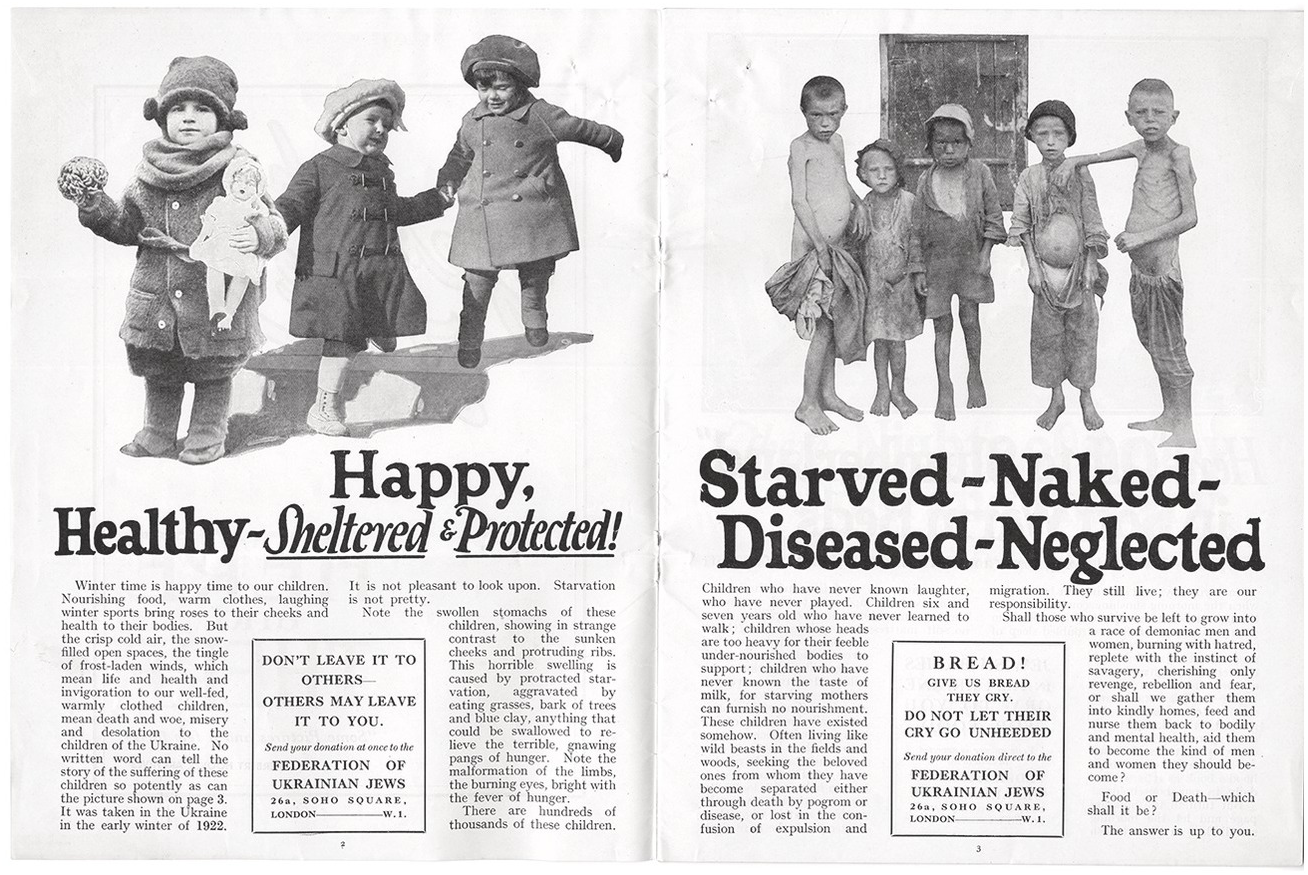

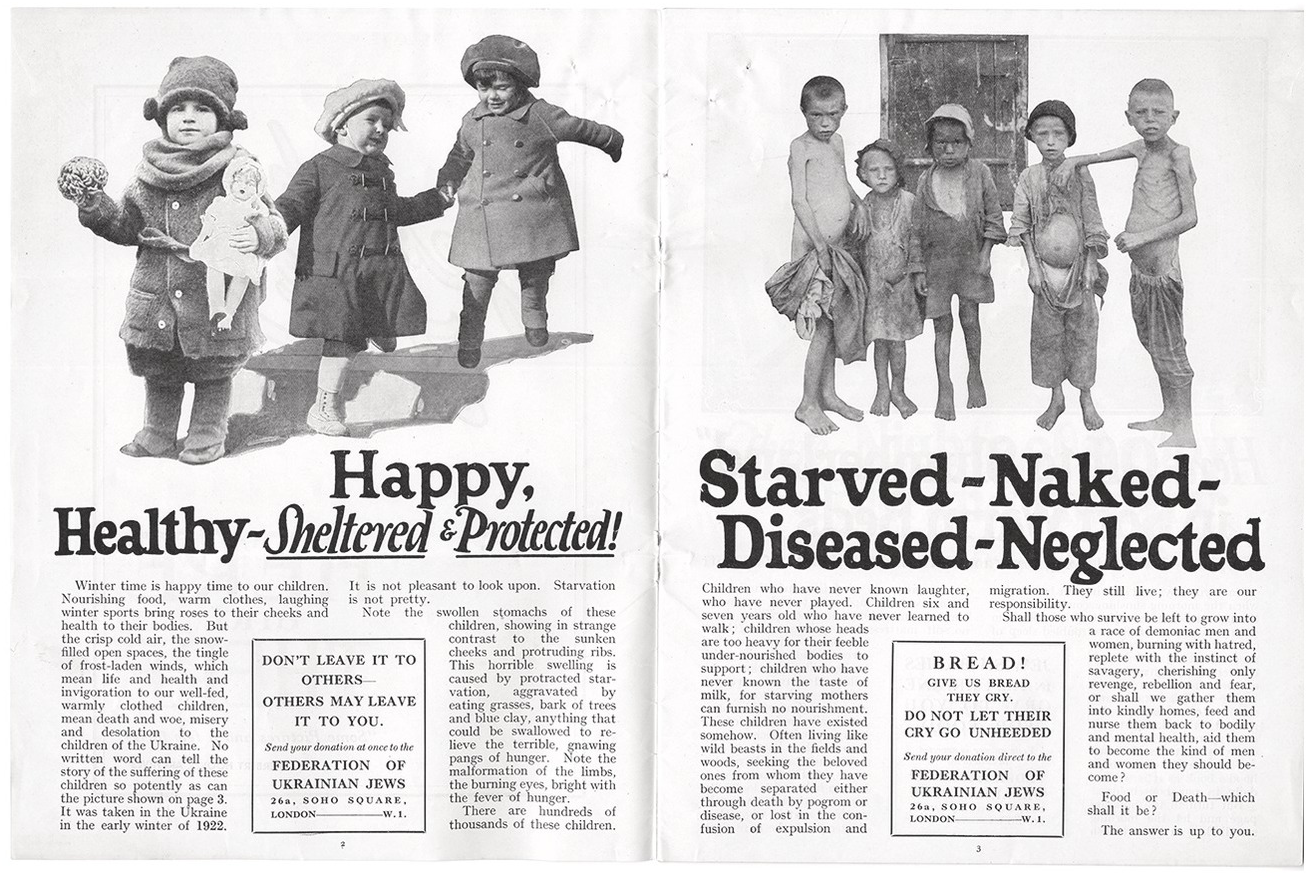

By 1920, children had become the ‘quintessential humanitarian subject’ and ‘descriptions and depictions of children’s bodies were closely linked to humanitarian appeals’ (see Figures 3.4, and 3.5).Footnote 166 The innocent child as a victim had become a humanitarian means to an end, as it exemplified both the horrors of wars and catastrophes as well as the hope for a better future.Footnote 167 Consequently, not only the SCF, but the ARA and affiliated organisations, as well as several Red Cross societies, spoke exclusively about children in their first public commitments and appeals. A European campaign by artists and writers, supported by the WIR and Nansen, ran under the slogan ‘For Our Little Russian Brothers’, and even the FSR asked its audience to answer ‘the cry of children whose fathers died by bullets supplied to the counter-revolutionary … by American, British and French imperialists’.Footnote 168

To evoke maximum feelings of pity, descriptions of needy children were often embellished with hyperbole. For example, children were said to have ‘hands like claws’ and ‘only their big dark, wondering eyes give any indication of the childish beauty gone forever’.Footnote 169 An early SCF report depicted the situation in a children’s home as follows: ‘Little cots each containing a little shrivelled form, its eyes staring out of a head which seemed nothing more than skin stretched tightly over a skull, with a little mouth that gasped out a mute appeal for help, as a fish gasps for breath when taken out of water.’Footnote 170

Texts like these led to criticism that the SCF was making ‘capital out of popular emotions’. However, an article in The Record readily conceded that this was the intention. Helping others, the author claimed, was a primitive instinct and charities in general, and the SCF especially, capitalised on this instinct.Footnote 171 Individuals and groups from Russia used this strategy as well, and thrust themselves upon their Western addressees with descriptions of cannibalism, suicide, and murder, hoping this would open their hearts and purses.Footnote 172

Photos and postcards, often depicting children in dire need, were widely circulated, mostly with a calculated shock effect.Footnote 173 In articles and pamphlets, pictures of children were also used to illustrate a before–after development, a humanitarian strategy that was already some decades old, showing the effects of the feeding programme, as well as providing a here–there contrast between children in the West and in Russia (see Figure 3.5).Footnote 174 For the SCF, campaigning and propaganda were embedded in public relations programmes and often designed by mass media experts. The cornerstones of effective communication were ‘originality in announcements, designs, speeches’, ‘simplicity and clearness’, and constant repetition. As in the advertising industry, it was considered ‘necessary to strike the same nail and to strike for a long time in order to drive it in deeply into the consciousness of the unknowing crowd’.Footnote 175

However, it was realised at the time that the adoptation of business methods could raise ethical problems. An article by the noted author and playwright Israel Zangwill ridiculed this development by presenting charity slogans like ‘Try our cheap charity – Certified pyre’, ‘Ten thousand war orphans – guaranteed genuine’, and ‘Good deeds at a unique discount’.Footnote 176 Ruth Fry, head of the Friends’ Emergency and War Victims Relief Committee (FEWVRC), viewed the increasing influence of public relations techniques on the humanitarian sector sceptically. For Quakers, she suggested, ‘relief is propaganda’. However, as this propaganda was a reflection of fieldwork rather than a public relations effort, it remained ‘free from the sting and stigma it would have had, had it been undertaken of set purpose’.Footnote 177 Fry’s moral concerns seem to have had little practical impact: like the SCF, the FEWVRC hired publicity staff and acknowledged the correlation between advertising expenditures and income.Footnote 178

Like the SCF, the ARA knew that providing businesslike relief was not enough to win public goodwill, and that propaganda had to deal with ‘human suffering … as emotional arguments have greater carrying power … than scientific or statistical analysis’.Footnote 179 The ARA press department was, therefore, eager to receive usable information from the famine front.Footnote 180

The medium of film became part of the campaign, and the SCF, ARA, ICRR, Quakers, and FSR produced films or documentary clips that were shown to a broader public and during fundraising events.Footnote 181 However, it seems that the SCF alone was wholeheartedly convinced by the medium. They adopted the motto ‘Seeing Is Believing’ and put great efforts into promoting their famine movie. An article in The Record suggested that the film aroused ‘emotions akin to those engendered by an autopsy’ among members of the audience. Moreover, the camera provided ‘incontrovertible evidence of the ravages of the famine’ and proved all those who had denied its death toll and criticised the work of the SCF wrong. Those who nevertheless still doubted were said to be ‘deliberately condemning them [the children] to death’.Footnote 182 However, the direct financial return of the famine film was disappointing, and the SCF admitted that at many screenings only a handful of viewers were present.Footnote 183 The ARA, on the other hand, remained sceptical regarding the effectiveness of films as a fundraising tool. Its director general, Edgar Rickard, pointed out that ‘the history of our film ventures, starting with Belgium relief, have as far as I know produced nothing but anxiety’.Footnote 184

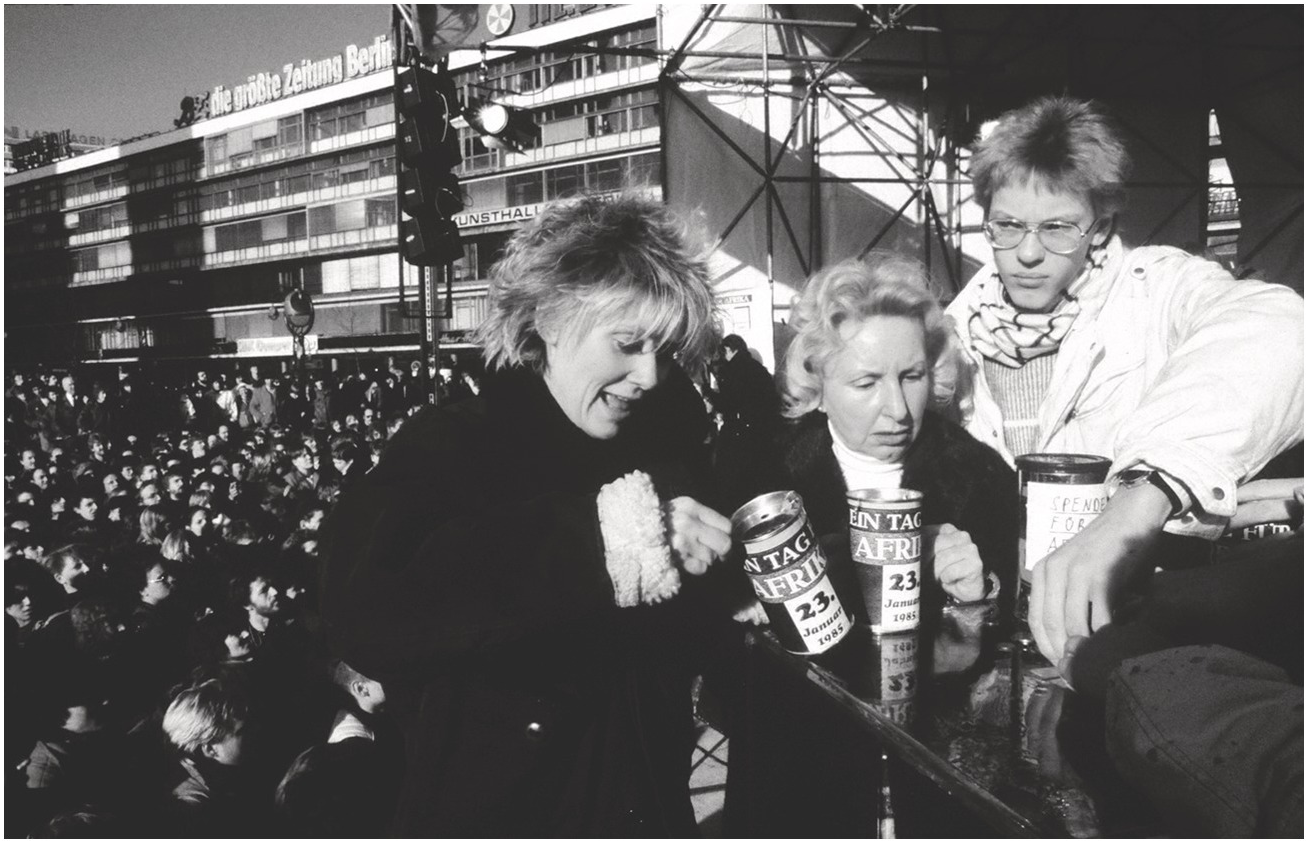

The coverage of the famine was especially evident during Christmas and Easter, when headlines full of pathos dominated the newspapers.Footnote 185 Holiday drives often included here-and-there comparisons, contrasting Western abundance with Russian deprivation (see also Figure 3.5): ‘As I look into the crowded shops [in London] I think of thousands of villages, very silent in a snow-covered land, where there will be no Christmas feast but only the moaning of the peasant families sitting at empty boards or lying down to die. Some of these I saw a week or two ago must now be dead.’Footnote 186 Even the ARA, otherwise reluctant to issue any kind of appeal, took the opportunity to encourage US citizens to buy food remittances as Christmas gifts. The organisers hoped doing so would widen the donor community, as ‘the actual saving of lives at Christmas will appeal to many charitable Americans having no relatives or friends in Russia’.Footnote 187

In the end, not even the communist FSR could afford to refrain from mounting an appeal. Among other things, it organised a ‘Nation-Wide Holiday Drive’,Footnote 188 sold Christmas stamps, and organised a campaign called ‘A Million Meals for a Million Russian Orphans This Christmas’ to collect one million dimes, representing an equal number of meals, for which every donor received a ‘handsome certificate’.Footnote 189 Despite many similarities, the slogans used by communist organisations sometimes differed from those of other agencies. Even during holiday campaigns, they did not fail to refer to the international class struggle: ‘At Christmas, profiteers buy pearl necklaces for their mistresses, but the class conscious worker makes a gift of food for his starving Russian comrades.’Footnote 190 In addition, socialist holidays, like the anniversary of the October Revolution, were used to advantage for fundraising purposes.Footnote 191

Self-interest as a Fundraising Strategy

Another way of coping with the ‘helping the enemy’ dilemma was to minimise the altruistic dimension of relief and stress that national and individual self-interest was served by helping Soviet Russia. Nansen justified Norway’s governmental aid in a statement to the Assembly of the League of Nations in Geneva by suggesting Russian relief would contribute to the economic stabilisation of war-ridden Europe. In the end, he alleged, it was not ‘humanitarian sentiment’ but ‘cold economic importance’ that determined the Norwegian government’s actions in this question.Footnote 192 A conference organised by the International Committee of the Red Cross in Berlin in December 1921 passed a resolution embodying a similar notion, namely, that the world economy depended on the restoration of Russian markets and production.Footnote 193

Hoover was an outspoken anti-Bolshevik, but since the ARA relied on public funding, he emphasised US self-interest as being served by famine relief, which he described as an ‘act of economic soundness’.Footnote 194 When lobbying for congressional funding, he argued that buying grain would stabilise the market and thereby help US farmers. ‘Helping ourselves helps others’ was President Warren Harding’s summary of this idea in a speech on Russian relief in December 1921.Footnote 195 However, this strategy allowed Russian leaders to understate the altruistic dimension of Western help and their own debt of gratitude, depicting food aid as a capitalist endeavour.Footnote 196 When the humanitarian enterprise in Soviet Russia reached its peak in 1922, Leon Trotsky stated that ‘philanthropy is tied to business, to enterprises, to interests – if not today, then tomorrow’.Footnote 197 Trotsky’s depiction of humanitarian aid as donor driven is shared by many modern commentators.Footnote 198

Even relief organisations with a more cosmopolitan and altruistic profile, like the SCF, used economic reasoning in their campaign, arguing that if Russia were to enter world markets again, unemployment at home would be reduced.Footnote 199 Relief for Russia therefore appeared as ‘an investment rather than an expenditure’, and it was further claimed that ‘no [other] investment would bring so great a return’.Footnote 200 Although pursuing spiritual aims, the Papal Relief Mission was in a way also investment-oriented. Current research confirms the claims of contemporary critics that its efforts were guided by the hope of reclaiming ground it had lost to the Orthodox Church, rather than simply by benevolence as such.Footnote 201

To critics wary of stabilising an enemy regime, Hoover replied that the ARA campaign was not about helping a Bolshevik country, but about helping a country that anticipated a regime change in the near future. The relief campaign would contribute to this by securing the good will of the Russian people. Hoover believed that relief for Soviet Russia was the most effective way to halt the ‘Bolshevik disease’ from spreading into Europe, and perhaps even heal Russia herself of it. US relief would enhance democracy and give the USA an advantage over Europe in future competition for untouched Russian markets.Footnote 202 For Hoover, in the long run, gratitude and the resulting moral credit was a political means to an end, which is why the ARA took measures to ensure that recipients knew their food came from the USA.

The rhetoric urging the West to counter the spread of a disease was also meant literally. Labour MP George Nicoll Barnes, in a parliamentary debate about British governmental aid, warned that ‘disease stalked behind hunger and cold’, it being the government’s responsibility ‘to stop that westward march’.Footnote 203 The SCF reminded its compatriots that ignoring the famine was not an option, as ‘even Britain’s geographical insularity would not preserve her from the possibility of a scourge analogous to the Black Death of the fourteenth century’.Footnote 204 The German Red Cross likewise justified providing relief to Soviet Russia so that a cholera epidemic might not spread to German territory. Consequently, its efforts were concentrated on medical relief.Footnote 205

Motivating and legitimising famine relief on the basis of self-interest caused a sense of unease, especially in the SCF and among the Quakers. Hoover was also warned by a US senator to ‘not dilute our generosity with any selfish purposes’.Footnote 206 A major article in The Record stated that it was depressing to read constant appeals to economic self-interest. It might well be ‘that men are unemployed in England because Saratov is starving’, but if we let the Russians perish, the author argued, we will suffer greater losses than potential economic markets: ‘then we shall be killing our own humanity within us, and we shall soon show the signs of it in increasing brutality, in social misery and in personal desolation’. Such reasoning downplayed empathy for the hungry and stressed psychological well-being of the donors. The crucial issue was no longer that millions were dying, but that ‘others are willing to let them die’. A people who would let this happen were seen as ‘morally doomed’.Footnote 207 The images of starving Russians, a fundraiser warned, would pursue those unwilling to give ‘like a remorse’ for the rest of their lives.Footnote 208

This change of perspective towards the donor also prevailed when relief agencies invoked a nation’s reputation. Some organisations, like the Imperial War Relief Fund (IWRF), employed a nationalist rhetoric in which altruism was presented as a genuinely British trait. In such a context, even donations benefitting former enemies could be exalted as acts of true patriotism, demonstrating the nobility of the British race.Footnote 209 Similarly, the ARA suggested to its donors that their aid was carrying ‘American ideals’ to the Russians.Footnote 210

For smaller nations, participation in international relief offered an opportunity to demonstrate their sovereignty and gain foreign prestige.Footnote 211 Lord Robert Cecil of the IWRF considered it humiliating that Britain was being surpassed, not only by the USA, but by her former colonies, Canada and New Zealand, when it came to providing government funds for Russian relief. In like manner, the German Red Cross observed that Germany could hardly stand by while the whole civilised world was sending relief.Footnote 212 Afterwards, that country’s commitment would be praised as illustrative of the ‘German willingness to make sacrifices’.Footnote 213