We discussed in the Introduction how a Foucauldian theoretical apparatus could help us identify and examine the specific discursive connections linking Parmenides to Homer, extended deductive argumentation and demonstration to narrative poetry. In fact, I shall hone in on a rather a small subset of the grand archaeological system that Foucault details in his Archaeology of Knowledge. There, in section II of chapter 5, devoted to ‘The Formation of Concepts’, one finds a discussion of ‘forms of succession’, the different sets of patterns or rules that dictate the arrangement of statements in their sequence.Footnote 1 Foucault identifies three ‘forms of succession’, and these will provide the framework for the rest of this chapter and much of what follows in the rest of the book.Footnote 2

After addressing the Foucauldian apparatus briefly, I shall then spell out my purposes in using these terms in the remainder of the book; my strategy will be to contextualize each of these three ‘forms of succession’ within the existing field of scholarship on Homer and narrative more generally (Section 3.1, ‘The Theoretical Apparatus in Context’). I shall then put these terms to work by examining the text of the Odyssey more generally (3.2, ‘How the Hodos Organizes Homeric Discourse’) before addressing the portion of that text most crucial for Parmenides, the first half of book 12, in Chapter 4. What will emerge is that the hodos has the capacity to organize the shape and structure – the ‘forms of succession’ – of a discourse, in this case Homer’s text, in a distinctive way. I shall ultimately argue that the shape and structure of the discursive organization delineated in this chapter provides a blueprint of Parmenides’ groundbreaking extended deductive argumentation, the topic of chapters 5 and 6.

Perhaps the most important level of analysis of the ‘forms of succession’ is the most macroscopic of the three, the level of the ‘rhetorical schema’. Foucault defines this as the rules or patterns according to which ‘descriptions, deductions, definition, whose succession characterizes the architecture of the text, are linked together’.Footnote 3 A core claim developed in chapters 5 and 6 is that one of the main levels of continuity between the first half of Homer’s Odyssey 12 and Parmenides’ ‘Route to Truth’ is to be found at the level of the rhetorical schema. Tracing this continuity will give us a decisive insight into both Parmenides’ strategies for refashioning his ‘new way of thinking and knowing’ and the underlying ‘architecture of the text’ that determines the shape and structure of his extended deductive argument.

The second and third levels Foucault articulates are the ‘ordering of enunciative series’ and the ‘levels of dependence’, respectively. The categories discussed under the rubric ‘ordering of enunciative series’ are in fact the same categories that elsewhere traffic under the name ‘Discourse Modes’, ‘Text-Types’, or, more traditionally, ‘Rhetorical Modes’.Footnote 4 In Foucault’s scheme these are three in number: we may refer to them here by their more familiar names, ‘narration’, ‘description’, and ‘argument/inference’. Foucault does not define the ‘levels of dependence’, electing instead simply to exemplify them; the examples given include ‘hypothesis/verification, assertion/critique, general law/particular application’. Although Foucault stresses that ‘types of dependence’ between units of statements need not be ‘superposable on’ the categories that comprise the ‘orderings of enunciative series’, that is in fact precisely how I wish to make use of these categories in the analysis to come. More specifically, I shall take the ‘orderings of enunciative series’ as the base units of analysis in my discussion of various hodoi elaborated in the course of the Odyssey, and, with these in hand, shall attempt to see how the rhetorical schema governed by the figure of the hodos determines an overarching pattern of organization – a discursive architecture distinctive to the figure of the hodos – out of these base units.Footnote 5

If it is dry work to summarize technical aspects of Foucault’s system in the abstract, the application of this schema in what follows will make it clearer what precisely is meant by the terms in question, and how they work. I shall undertake this in Section 3.2; the next step, however, is to anchor Foucault’s apparatus in current discussions in Homeric scholarship.

3.1 The Theoretical Apparatus in Context

3.1.1 The oimē, Themes, and Rhetorical Schemata

At first glance, Foucault’s notion of a rhetorical schema might be thought to approach two topics in Homeric studies: the use of metapoetic devices, and so-called catalogic discourse. The latter we shall explore below (see Section 3.1.4); the former we shall examine here, in large part to clarify one way in which I do not intend to use Foucault’s term when discussing epic poetry.

Scholars have discerned a number of metapoetic images at work at various points in the Iliad and the Odyssey. According to one view, the poem is a craft production, an object constructed in the manner of Odysseus’ raft, for example, or his well-made bed.Footnote 6 According to a more well-developed tradition, the Homeric text has been seen to emerge at the intersection of imagery related to weaving and sewing.Footnote 7 The unavoidable point of comparison in this context, however, is the oimē, or ‘path of song’.Footnote 8

Although there may seem to be many tantalizing similarities between the oimē as a metapoetic figure and what we shall examine under the rather cumbersome name of the ‘rhetorical schema of the figure of the hodos’, caution must be exercised.Footnote 9 One prominent conceptualization of the oimē takes each particular segment of the path to be a ‘theme’ in the Parry–Lord sense;Footnote 10 the idea is that these oimai are ‘tracks cut into the landscape’ that link together end on end and, taken collectively, define a ‘map’ of Epos.Footnote 11 Are these oimai, perhaps, coextensive with Foucauldean rhetorical schemata?

The answer, at least in this book, is no. The reason the answer is no depends in part, however, on just what it is that one means by oimē. The way that the word is used in the Odyssey suggests that an oimē in fact comprises a relatively large unit. Demodocus’ postprandial performance, described in terms of an oimē in one of only three passages where the word appears in Homer, encompasses ‘The Quarrel of Odysseus and Achilles’; later, Odysseus will ask him to ‘move along [the path of song] and sing “The Fashioning of the Wooden Horse”’.Footnote 12 These are both apparently rather lengthy productions; if that is the case, their scale is larger than that to which the rhetorical schema of the hodos will refer. (For comparison, Circe’s foretelling of Odysseus’ hodos in Odyssey 12, the central example of the rhetorical schema of the hodos that I examine below, occupies slightly more than 100 lines (12.27–141) of the four books of aoidē Odysseus makes it through in a single evening with the Phaeacians; one hardly imagines that Demodocus discharges his duties with such brevity.) On this understanding, an oimē would seem to be something considerably longer than the amount of text governed by a rhetorical schema, at least as we find it in Homer.Footnote 13

Other discussions of the oimē emphasize the idea that it is something that a poet can hop on or off at any number of points along the grand path of Epos as a whole. On this view, as a poet performs, ‘no matter how small the scale of the performance’ he or she would simply be on the oimē, the ‘path of song’, in virtue of orally performing a poem.Footnote 14 There is an important question, not always clearly expressed, about whether this idea should focus on the word-by-word, line-by-line process of bardic composition, or whether individual units on this larger epic path of song correspond to something closer to a Parry–Lord ‘theme’.Footnote 15

In the first case, the claims scholars have made about the way that the structure of a text conforms to certain patterns – and is perhaps even dictated by certain rules – are very much of the sort I shall develop below. Here again, however, there is an important difference of scale. This strand of analysis of the ‘path of song’ addresses units of text – phrases and lines – of a smaller scale than I intend to investigate via the term ‘rhetorical schema’; rather, units of text of this size are better discussed under the rubric ‘types of dependence’, addressed in Section 3.1.3 below.

In the second case, it is possible to imagine the relationship between a theme and an oimē as corresponding to, or perhaps instantiating, a form of the narratological distinction between story and plot or narrative. This is an attractive hypothesis, and it opens a vista onto an exciting perspective of Homeric poetics. But any such relationship between story and narrative is also different in kind from the relationship I wish to capture under the term ‘rhetorical schema’. Why so? If, on the one hand, any theme can be expressed along the path of song (and, on this view, all themes necessarily would be) and, on the other, every path of song maps onto simply one or another of the ‘themes’ in the mythic repertoire, then the level of connection between the content of the story (the theme) and the manner in which it is narrativized (via movement along the path of song) as plot is necessarily a rather general one.Footnote 16 By contrast, as we shall see, the rhetorical schema governed by the hodos, at least as I examine it here, dictates a far more precise relationship between story and narrative. While it is undoubtedly valuable to combine the two understandings of oimē as ‘theme’ and ‘path of song’,Footnote 17 current scholarship on this topic allows for considerable flexibility in the relationship between the level of story and the level of plot – and this gap between the more macro structure of a theme and the micro structure of a visual poetics of the oimē is precisely the gap filled in part by the rhetorical schema that will be so important in what follows.Footnote 18

3.1.2 Text-Types, Discourse Modes, and Enunciative Modalities

Classic studies of text-types define these to be ‘underlying (or overriding) structures that can be actualized by different surface forms’.Footnote 19 On the traditional view, there is always a single, dominant (underlying or overriding) text-type that characterizes any given text. Because the roots of this approach to textual analysis are to be found in literary criticism, the text-type ‘narration’ has received the most attention and usually serves as the central, positively constructed term against which other text-types are negatively defined.Footnote 20 Two aspects of narration are usually deemed key characteristics: first, that narration depicts ‘events or sequences of events’ and, second, that the ‘order in which events happen is significant’.Footnote 21 By contrast, description is ‘oriented to the statics of the world – states of affairs, enduring properties, coexistants’;Footnote 22 it often introduces elements of the story-world – persons, places, things – and/or attributes qualities to these elements.Footnote 23

While in the case of narration the text’s underlying progression is primarily temporal, in the case of description the text’s underlying progression is primarily spatial.Footnote 24 Scholars have often claimed that important implications follow from this. As noted, the narration of events whose temporal order is significant endows their narration with ‘a natural principle of coherence, one that enables the narrator to construct his presentation sequence … according to the logic of progression inherent in the line or chain of events itself; from earlier to later’; by contrast, and significantly for the analysis to be undertaken here, ‘the descriptive sequence’ is denied ‘any natural resource of coherence’.Footnote 25

More recently, the study of discourse modes, a linguistically inspired method of analysis, has emerged in parallel to the study of text-types.Footnote 26 The key insight animating this enterprise is that several features of the surface text preponderate in – or are understood to be the hallmark of – narrative or descriptive portions of text.Footnote 27 We may note three features.

First, verb forms. Tense-aspect in particular has long been recognized as ‘the most important distinctive linguistic feature’ associated with each of the text-types or discourse modes.Footnote 28 Reflecting the fact that narration is usually defined in connection with the notion of the event, the aorist and historical present are often intimately associated with narration; so, too, as we shall see, is the future tense when the narrative takes the form of a ‘prior narration’.Footnote 29 Person and mood also prove significant: description does not use the second person or the imperative mood, both of which can be found in narration.

Second, the notion that the underlying progression of the text is temporal in narration and inherently unordered in description has a correlate at the surface level of the text. This can be seen from two perspectives: from the perspective of the story and from the perspective of the plot. On the one hand, narrative portions of a text usually progress along with time in the story world; on the other, the passage of time in the story-world is most commonly expressed through, or recorded by, a sequence of narration. By contrast, movement through a descriptive passage does not necessarily suggest the passage of time in the story-world, nor does the passage of time in the story-world necessarily register in passages of description.Footnote 30

Third, textual progression is often marked by temporal adverbs (or combinations of temporal adverbs and specific particles) in the case of high-narrativity portions of text. On the other hand, spatial adverbs (or combinations of spatial adverbs and specific particles) predominate in high-descriptivity sections.Footnote 31

So much for narration and description. What of argument? In fact, typologies of ‘argument’ are much harder to produce. There are three obstacles. First, the topic is under-researched, and analysts of discourse modes or text-types have simply not devoted much attention to differentiating ‘argument’ from ‘description’ or ‘narration’.Footnote 32 Second, in cases where analysts have undertaken this task, their definitions of ‘argument’ are usually so inextricably bound up in a formal, modern understanding of what constitutes an argument that it is difficult to apply such a category to a pre-Aristotelian text like the Homeric poems.Footnote 33 The third stems from Parmenides’ own role in developing argument (and, specifically, extended deductive argument) and the fact that he is a key point of transition in the forms that an argument might take. Since this very transition is the central topic under investigation here, as noted in the Introduction, deciding what constitutes an ‘argument’ without already assuming the accomplishment of the phenomenon whose development we are attempting to observe is a problem.

For the purposes of this project, I shall consider a portion of text to instantiate an ‘argument’ discourse mode if it is formed of a cluster of statements that are linked inferentially; that is, if it is formed of a cluster of statements some of which explicitly provide a justification or rationale for others.Footnote 34 At the surface level of the text, argument sections will be particularly densely populated by conditional clausesFootnote 35 or purpose clauses, which tease out the implications of certain actions or justify pieces of instruction, and by specific usesFootnote 36 of epeiFootnote 37 and garFootnote 38 (to be examined in further detail below).

3.1.3 A-B-C Patterns, and Types of Dependence

Some long-standing conversations in Homeric scholarship, particularly classic studies on catalogues and battle scenes, provide important parallels for the notion of a ‘type of dependence’.Footnote 39 In the Catalogue of Ships, for example, every entry is organized in relation to (a) ‘nation/generals’, (b) ‘places’, (c) ‘number of ships’;Footnote 40 in some instances, further genealogical background for key protagonists is provided.Footnote 41 These categories can also be examined under a more general typology where anecdotes supplement the ‘basic information’ (e.g. names and places in the Catalogue of Ships) with biographical information, while ‘contextual information’ offers ‘what is relevant to the context’ in which the list occurs.Footnote 42

Somewhat more recently, Egbert Bakker has suggested that the so-called A-B-C pattern detailed above is the product of an oral compositional technique that operates through a process of ‘framing’ and ‘goal-setting’:Footnote 43 the basic information demarcates the frame of vision and ‘orients’ listeners as to the future direction of the text.Footnote 44 Detail ‘added’ to the ‘frame’ ‘lends depth and significance’ to the goal, which is the event presented.Footnote 45 By means of this repeated pattern of elements, the epic narrator opens up narrative space, provides direction, and intensifies the experience of listeners.Footnote 46

I shall argue in Section 3.2 below and in Chapter 4 that the rhetorical schema governed by the figure of the hodos makes available a framework of relationships between discursive units (i.e. its own distinctive ‘type of dependence’) that operates in a manner closely paralleling the A-B-C pattern and Bakker’s elaborations on it.Footnote 47 This framework need not be exploited but is available to be activated any time the figure of the hodos is mobilized, as Circe’s two long speeches in Odyssey 10 and 12 make clear.

3.1.4 Catalogues

Discussion of the A-B-C pattern brings us to one final topic of Homeric scholarship that needs to be addressed: the notion of catalogic discourse. A great deal has been said about this topic, its relationship to oral composition, the development of epic narrative forms, and its cognitive functions and their place in a society that is either preliterate or largely so.Footnote 48 Scholars have discussed three principles of catalogic discourse that are pertinent in this setting: that there is some kind of underlying classificatory rubric according to which catalogued items merit inclusion in the catalogue;Footnote 49 that these items form the entries – often specifically delimited by ‘entry headings’ – that make up the catalogue;Footnote 50 and that these entries are enumerated sequentially.Footnote 51

It is this final point that will prove the most crucial for the remainder of this chapter, and indeed much of the remainder of this book. How are the entries to be ordered? There may seem to be two extremes. On the one hand is the list: ‘a list presents items that are more than one in number … and have something to do with each other; but quite unlike narrative, the order of its items may be reversible or subject to free transpositions … the actual order of entries need not follow any scheme or have any obvious significance.’Footnote 52 On the other hand is what we might call a series, where the order of the items catalogued is not reversible or subject to free transpositions but is strictly determined according to some rule or principle. An example of a Homeric list would be the catalogue of Nereids at Il. 18.38–49; is there any sense that it matters whether or not Glauke comes first, Amatheia last, and Doto and Proto in the middle? By contrast, an archetypal epic series can be found at lines 133–53 of Hesiod’s Theogony (or even the parthenogenic portion at lines 126–32). There is simply no question of Gaia coming after, say, Cronus or the Cyclopes (or even the mountains or Pontus): because she begets them, she must plainly precede them.

3.2 How the hodos Organizes Homeric Discourse: Forms of Succession

Ulysses’ journey, like that of Oedipus, is an itinerary. And it is a discourse, the prefix of which I can now understand. It is not at all the discourse (discours) of an itinerary (parcours), but, radically, the itinerary (parcours) of a discourse (discours), the course, cursus, route, path that passes through the original disjunction.Footnote 53

In the Odyssey, the successions in the narration are regulated by the scheme of the path, thus preserving the primacy of catalogic discourse.Footnote 54

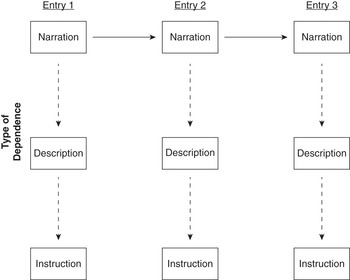

It is time to put these distinctions to work. My fundamental claim comprises the following components. The hodos, understood as a kind of catalogic discourse, structures the discursive architecture of portions of a text according to its own distinctive rhetorical schema; it yields a series, that is, by providing a set of rules or principles according to which items that form entries enumerated in the catalogue can be linked (articulating these rules or principles will be one of the main objectives of this chapter). This rhetorical schema in turn dictates its own distinctive manner of relating one to another the internal components that make up individual entries; this pattern will be examined in terms of a specific ‘type of dependence’. Finally, the base unit I shall consider for examination is the unit of the text that is defined by text-type or discourse mode, be it narration, description, or argument (see Figure 3.1).

Figure 3.1 Summary of the framework: The hodos and forms of succession

In chapters 5 and 6, I shall show how Parmenides reappropriates this framework for his own ends. More specifically, by retaining the rhetorical schema of the figure of the hodos but substituting claims about the nature of what-is in place of toponyms and place descriptions as the items that make up entries in the catalogic discourse of the hodos, he produced the first recorded sequence of extended deductive argumentation. Parmenides’ new creation will thus have the rigorous and clearly defined rules for sequential ordering of narration, as opposed to the ‘inherent unorderliness’ of description; it will also be made up of statements that address the statics of the world and its enduring properties, as opposed to actions and events. What we shall find, that is to say, is narrativity without narration and description without descriptivity – or, as we would call it, an extended deductive argument.

3.2.1 Catalogues: Constituting the Field of Statements

Understanding the discursive architecture governed by the figure of the hodos as a kind of catalogic discourse requires us to address three features of catalogues. First, catalogic discourse both demarcates the boundaries of a kind of closed set and structures the field of statements it encompasses in such a way as to facilitate the process of classification.Footnote 55 By grouping together a bundle of discrete entities – be they places, individuals, objects – within a single, unifying framework, catalogic discourse organizes the terrain of the field of statements in such a way as to suggest (or, from another perspective, presuppose) a kind of underlying conceptual unity that encompasses the items enumerated.Footnote 56 Second, the catalogic form can articulate the individual items it enumerates as discrete items by framing each entity as an ‘entry’ (with, furthermore, a particular quality that grants it membership in the catalogic set).Footnote 57 Third, by unifying in a single set the discrete entities it enumerates, the catalogic mode of discourse in general makes it possible to indicate the entire set and its component entities in a single shorthand.

An example may help illuminate these points. Unlike the later routes that traverse the fabulous spaces of the Apologoi, the journey Athena maps out in Odyssey 1 remains squarely within the bounds of the ordinary Greek world and is therefore perhaps the simplest, least elaborate journey spelled out in the Odyssey.Footnote 58 We discussed above (Section 1.2) the moment Athena sets the plot of books 1–4 in motion by proposing to Telemachus that he (Od. 1.284–91):

The sequential enumeration of the items – Pylos, Sparta, native land (Ithaca) – is evident. The lexical items that demarcate the entries and articulate the specific items, the pair ἐς and -δε (discussed above in Section 1.2), are equally clear. The underlying conceptual unity established across these items is a more complex question.Footnote 59

Third, the itinerary, with its clear point of origin (where we are now: in this case, Ithaca) and its precisely identified final destination (νοστήσας … ἐς πατρίδα γαῖαν), determines the boundary markers of a closed set, one that encompasses Ithaca, Pylos, Sparta (and Ithaca again). As a result of being fused into a single unit, the entire ordered sequence of places can be intensively summarized by the single word hodos (instead of requiring that each destination be listed extensively). Here the scene in book 1 proves particularly illustrative: two hundred lines and an afternoon’s worth of arguments with the suitors after Athena set the Telemachy into motion, we find Telemachus in his private chambers (Od. 1.443–44):

As a kind of catalogue, the hodos-itinerary marks out the boundaries of a category or the limits of a set. In the course of doing so it creates a distinct unit, the constituent elements of which can be summarized or indexed as a unit or as a bundle of different elements.

3.2.2a Rhetorical Schemata: The hodos Orders Places

The kind of discursive architecture organized by the figure of the hodos, then, is fundamentally catalogic in nature insofar as it enumerates items sequentially within a larger set susceptible to conceptual unification; in addition, it articulates the members in its set as discrete items through the catalogue’s system of ‘entries’. But what kinds of items fill entries in a catalogue, and what principles govern the order of the sequence in which they are enumerated? These are the two parameters that define the different species in the family of catalogues.

Some catalogues take as items the warriors of an army, and the principle according to which entries are sequenced is that of spatial contiguity.Footnote 60 Others take the trees in an old man’s garden sequenced according to a similar principle.Footnote 61 Yet others take living creatures as their items and order entries according to a principle of genesis or begetting: this is, of course, the genealogy. The genealogy is sometimes coupled with the hodos-itinerary as a complementary kind of catalogue, the former operating ‘temporally’, the latter ‘spatially’.Footnote 62 One can understand why (Od. 1.284–85, 291):

The items enumerated in this catalogue are toponyms (and therefore refer to places), and their position as an entry is demarcated by the spatially oriented lexical items (ἐς, -δε) that highlight them as such.Footnote 63

3.2.2b Rhetorical Schemata: The hodos Orders Places

Further consideration of the sequence according to which items in this mini-catalogue are enumerated, however, clearly reveals this simple binary between a ‘spatial’ and a ‘temporal’ conception of catalogic discourse to be incomplete. It is vital to appreciate here that the temporal dimension also plays an important role in configuring the rhetorical schema of the hodos; the figure of the hodos orders spatial relationships according to movement through space in time, with its linear, sequential flow. So, in the same example (Od. 1.284–85, 291):

This is where the distinction between a list and an ordered series becomes relevant: if the Catalogue of Ships orders men according to a principle of geographical (spatial) contiguity, we might imagine a Catalogue of Places that simply takes the toponyms, rather than the names of the warriors who dwell there, as the items in its entries.Footnote 64 Like the hodos spelled out by Athena, it, too, would be formed of items united by their underlying spatial nature. What we find above, of course, is something radically different: as the sequence of particles and adverbs πρῶτα μὲν … κεῖθεν δὲ … δὴ ἔπειτα makes explicit, the order in which these place items occur is not reversible or, as Sammons puts it, ‘subject to free transpositions’; rather, their sequence seems determined by an underlying principle or pattern. The hypothetical Catalogue of Places would, as a catalogue at least (and a repository of information), be the same whether it began with the poleis of Thessaly or Boeotia, whether the islands of the eastern Aegean led to those of western Greece or the other way around;Footnote 65 the Catalogue of Ships (or hypothetical Catalogue of Places) shares important features, that is, with the list.Footnote 66 By contrast, Telemachus’ itinerary would by no means be the same were he to begin with Sparta and return to Ithaca by way of Pylos – for a variety of reasons, logistical and narrative. The order of the sequence matters: the rhetorical schema of the hodos structures the items that form entries in a series. More specifically, it orders a series of spatial items (places) according to a temporal progression.Footnote 67

3.2.2c Rhetorical Schemata: Narrativity of the hodos-Itinerary

But what dictates the order of this progression? What principle or set of rules determines the order of the sequence by which may be enumerated the items that make up the hodos announced by Athena? We may note that closely tied up with the temporal dimension that is constitutive of the hodos-itinerary is the implicit need to move – in time – from one place-item to another. This element of action is another of the main aspects distinguishing the hodos from the hypothetical Catalogue of Places. Another look at the same passage reveals this activity-based dimension:

Above, we defined narration as ‘the representation of an event or sequence of events’, a sequence where, furthermore, ‘the order in which events happens is significant’.Footnote 68 Even stripped to its essentials, it is clear that the skeleton ‘[f]irst to Pylos, then to Sparta, finally home’ implicitly contains the ‘events’ ‘[f]irst [go] to Pylos, then [go] to Sparta, finally [go] home’. The progression of the text tracks this significance and marks it out explicitly with the string of temporal adverbs πρῶτα, κεῖθεν, ἔπειτα. Events are likewise presented in the aorist and/or imperative, features closely associated with the discourse mode of narration. It is thus the narrativity of this portion of text (as a result of which the ordering of events is significant) that imparts a necessary order to the sequential enumeration of places that make up entries in Athena’s hodos-catalogue.

3.2.3 Rhetorical Schemata and Types of Dependence: A Temporally Ordered Sequence of Places as a Framework for Description

That is not all, however. The story is more complex. So, too, is the first hodos that Circe delineates for Odysseus, the one we find in Odyssey 10. It may take no special knowledge to sign out the path from Ithaca to the mansions of Nestor and Menelaus on the familiar terrain of the Peloponnese; what emerges there is the significance of the sequence in which these visits are ordered. The same is not true of the route from Aeaea to the Underworld – for, as Odysseus laments, ‘no man has ever yet travelled to Hades in a black ship’ (Od. 10.502). Circe gives the following set of directions in response (Od. 10.505–16):

In this passage, we see on display the hallmarks of the discursive structure governed by the hodos: a bounded range of places ordered sequentially (the end of Ocean and the fertile shore; the hinterlands of Hades; the confluence of Pyriphlegethon and Cocytus into Acheron and rock) in a unified set. This sequence is dictated by a narrative framework, one in which movement through space in time imparts a specific order to the sequences: (first, depart from here), then, when (ὁπότε) you have crossed the ocean you will find a thickly wooded shore, then from there go to the rock/confluence of Pyriphlegethon and Cocytus; then … etc.Footnote 69

We may, however, note two important points, one concerning the level of rhetorical schemata, the other the level of types of dependence. At the level of rhetorical schemata, we have seen that it is movement through space in time that imparts the specific shape to the order of the items sequenced by the hodos as catalogic discourse. But this example urges us to take proper account of the fact that this is movement through space in time, and to pinpoint the ways this spatial dimension exerts its own influence on the possibilities for ordering the items that make up the catalogue of a hodos-itinerary. In the hodos to the Underworld, the scarcity of any temporal indicators imposing a temporal sequence on the catalogue at the level of the text brings out the underlying order inherent in the enumerated items themselves. Not only are both the spatial and the temporal dimensions of the pattern by which the hodos orders its sequence distinct and irreducible one to the other, but this spatial dimension is topological: that is, we understand space here from the perspective of the spatially contiguous, rather than absolute Cartesian space.Footnote 70

Let us consolidate observations made so far at the level of rhetorical schemata. Crucially, the rhetorical schema of the hodos has a fundamental narrativity insofar as what it depicts are events or actions, and, characteristically, the sequence of these actions or events is significant. The order in which these events or actions are sequenced in turn depends on two parameters. The underlying geography of the space traversed – specifically, the contiguity of the places where events or actions occur – determines the matrix of possible combinations this sequence can take. Movement through this space in time in turn determines one sequence or imposes a clear shape and form on the set of possibilities determined by the underlying geography of the space traversed. That is, the hodos dictates a series insofar as, by adding a dimension of ordered temporal sequentiality, it generates what we might strategically call spatio-temporal con-sequence out of spatial contiguity.

At the surface level of discourse these features are reflected in a number of characteristic ways in the Homeric examples so far examined. First, the verbs linking the units ordered by the rhetorical schema of the hodos are in some combination of the aorist tense-aspect (as one would expect with events and actions), the imperative mood, and the second person. Second, the combinations of adverbs and particles indicate the progression of the text according to a sequential pattern (and, especially in the hodos described in Odyssey 1, a largely temporally determined sequence). But this is because, third, the progression of the text tracks the sequence of the underlying story, which is itself ordered according to a temporal progression through spatially contiguous locations.

The second major point, pertaining to the level of the ‘types of dependence’, is as follows. There is a subtle but significant shift between the items enumerated by Athena to Telemachus and those enumerated by Circe to Odysseus. In the first case, we found a series of place names – ‘Pylos’, ‘Sparta’ – marked out as entries by the lexical tags ἐς or -δε. In the hodos to Hades a similar tag, ἔνθα, designates ‘entries’ in the catalogue, too. This is quite important, given that toponyms seem hard to come by in the Underworld. In this wilderness bereft of proper names, some other means of designating a place must be found: a rock, a confluence of rivers, a grove.

Somewhere between the thickly wooded shore and Persephone’s grove (and the tall poplars, and the fruit-perishing willows), between the rock and Pyriphlegethon and Cocytus, we find ourselves edging away from narrative discourse towards descriptive discourse. This is not only because of the highly conspicuous substitution of the sequence of temporal adverbs πρῶτα, κεῖθεν, ἔπειτα by the tripartite anaphora of the primarily spatial adverb ἔνθα at lines 509, 513, 515;Footnote 71 the passage is equally rich with verbs in the omnitemporal present (ῥέουσιν, 513; ἐστιν, 514; along with unexpressed existential predicates at 509–10 and 515).

The second entry in Circe’s hodos-catalogue thus blossoms into a discursive mode fully marked by ‘high descriptivity’ characteristics. We find a series of pieces of information about what the story-world is like, a set of attributions that constitute subtheme-like items in relation to themes (theme ‘Cocytus’, subtheme ‘which is an off-break from the water of the Styx’), a listing of states of affairs that is the stock in trade of description and all the grammatical features that attend this function discussed above.

To recapitulate: even without any express signalling of the temporal dimension ordering the items sequenced by a hodos, the discursive mode governed by this hodos is still marked by a kind of narrativity thanks to the inherent significance of the temporal sequence of the events it encompasses. Second, it is not only this temporal dimension that defines the order in which the hodos sequences its items: the inherent geography and topology of the spatial items it enumerates plays a fundamental role in dictating the set of possible combinations that form the series of the ordered sequence of the hodos. Third, at the level of ‘types of dependence’, the ‘entry’ component of the catalogic framework creates a regular (in the sense of both ‘orderly’ and ‘repeated’) opportunity for interludes of descriptive discourse that present states of affairs, introduce objects and places and attribute qualities to them, and are marked by the linguistic features characteristic of description (spatial adverbs and verbs in the omnitemporal present, perfect, etc.).

3.2.4 Types of Dependence: Narrative Episodes Tied to Places

One final point must be addressed before moving to the more consequential of Circe’s two hodoi. Continuing with the passage above, we find (Od. 10.513–20):

While it is interesting to note how the ‘tag’ ἔνθα is used at line 515 to make the pivot from description-oriented discourse to narratively oriented discourse, the temporal adverb (μετέπειτα) and ordinal language (πρῶτα, τὸ τρίτον) clearly indicate the inherent significance of the ordering of events that is the hallmark of high-narrativity discourse. As we shall discuss at much greater length in the next chapter, the imperative mood here expresses the sequence of actions that constitute the narrative; this highly narrative level nested within a highly descriptive one, which is itself nested in the narratively sequenced catalogue of the hodos, often takes this verbal form in the Odyssey.Footnote 72 Furthermore, as the use of the imperative mood (in dashed underline), the use of the vocative, and the second person markers suggests, this level of discourse is used to convey instructions specifically pegged to the places that make up the catalogue entry and are described in the ensuing description section: we may therefore be more specific and call this level of dependence: ‘instruction’ (see Figure 3.2).

Figure 3.2 The figure of the hodos in Odyssey 10

3.3 Conclusions

The apparatus developed in the first section of this chapter (3.1) provided us with a toolkit to analyse key portions of the Odyssey where the figure of the hodos plays a key role in dictating the discursive architecture of a portion of the poem. As a form of catalogic discourse, the rhetorical schema of the hodos orders the entries that form it according to a distinctive sequence. The parameters governing the order of this sequence include both a spatial and a temporal dimension. Because the items that form entries in a hodos-catalogue are places (Section 3.2.2a), the spatial configuration of the places to be catalogued dictates the possible sequence in which they can be arranged on the basis of their geographical contiguity (Section 3.2.2b); on the other hand, in the hodoi we have seen enumerated in Odyssey 1 and Odyssey 10, the fundamentally narrative dimension of the human movement from place to place imparts a clear temporal order to the sequence of places catalogued; it configures what we have termed spatio-temporal con-sequence from spatial contiguity (Section 3.2.2c). This narrativity also gave the catalogue produced by the rhetorical schema of the hodos the quality of a series: the order of the places matters.

The example of the hodos through the Underworld enumerated by Circe in Odyssey 10 also reveals key features of a possible type of dependence governed by the rhetorical schema of the hodos. As we have seen, much as in the A-B-C pattern scholars have discerned in the Catalogue of Ships, the narrative frame of the catalogue provides an opportunity for portions of description to depend from each entry (3.2.3), and for portions of narrativity (in this case, instructions) to further depend from these descriptions (3.2.4).

With this basic structure of the rhetorical schema of the hodos and the types of dependence it can dictate in mind, it is now time to examine the second hodos that Circe spells out for Odysseus: the itinerary in Odyssey 12 that runs from her island of Aeaea and goes to Thrinacia, where the Sun pastures his cattle.