Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction: Breaking with the Past, Forging the Future

- 1 The New Woman of the Early Twentieth Century

- 2 Feminism and Jewishness in Viennese Literary Modernism

- 3 Theorizing the Sexual Crisis through Journalism and Sexology

- 4 Effecting Change through Literature: Die Intellektuellen (1911)

- 5 Sexual Sociology during the First World War

- Conclusion: Living the Sexual Crisis

- Bibliography

- Index

Introduction: Breaking with the Past, Forging the Future

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 January 2023

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction: Breaking with the Past, Forging the Future

- 1 The New Woman of the Early Twentieth Century

- 2 Feminism and Jewishness in Viennese Literary Modernism

- 3 Theorizing the Sexual Crisis through Journalism and Sexology

- 4 Effecting Change through Literature: Die Intellektuellen (1911)

- 5 Sexual Sociology during the First World War

- Conclusion: Living the Sexual Crisis

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

Vienna at the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth century, often referred to as fin-de-siècle Vienna or Vienna 1900, is characterized as overflowing with influential and vibrant intellectual innovation expressed through new advances in the creative arts, architecture, philosophy, science, and medicine. It was at this time that Freud was experimenting with dream analysis, hypnosis, and the talking cure while his so-called Doppelgänger Arthur Schnitzler brought the inner workings of the mind to the field of literature. It was also at this time that Klimt was creating his golden portraits; Arnold Schönberg was developing his theories of atonality in music; Theodor Herzl was shaping his ideas regarding political Zionism; and the architect Adolph Loos was declaring that ornament was a crime. Professor Ernst Mach, who held a chair at the University of Vienna in the history and philosophy of the inductive sciences, was quite popular among students from a wide range of disciplines, blurring the boundaries between the disciplines of philosophy and science, particularly in his discussions of sensory perceptions, inner experience, and changes in perspective. The pacifists Bertha von Suttner and Alfred Hermann Fried received the Nobel Peace prize, in 1905 and 1911 respectively, for their work in promoting peace. Meanwhile, as in most other urban centers at the time, an organized women’s movement was gaining strength and social-democratic ideas had gained political traction. It was in this atmosphere that Grete Meisel-Hess (1879–1922) emerged as a modernist feminist writer.

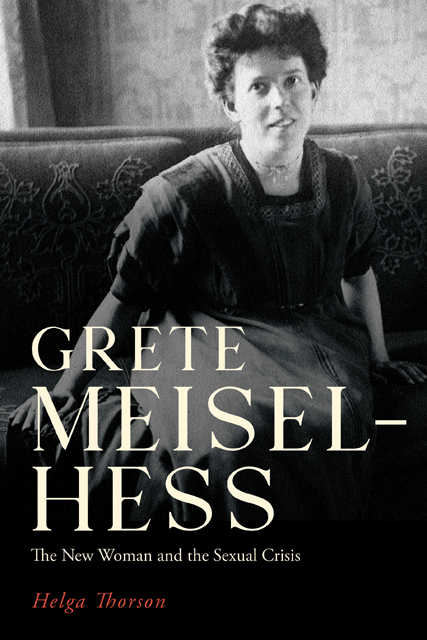

Grete Meisel-Hess supplied a feminist, Jewish voice to modernist discourses in the early twentieth century. Born in Prague to Jewish parents who later resettled in Vienna, Meisel-Hess became a significant literary presence in Vienna after the publication of her first novel, Fanny Roth: Eine Jung-Frauengeschichte (Fanny Roth: A Story for Young Women), in 1902. Her fiction as well as her sexual theories were influenced by many of her contemporaries, such as Sigmund Freud and Arthur Schnitzler, yet she also indirectly criticized their conceptions of gender and sexuality in her own works. Shortly after publishing her second novel, Die Stimme. Roman in Blättern (The Voice: A Novel in Sheets of Paper, 1907), Meisel-Hess officially relocated to Berlin, where she set herself up as a journalist while continuing to publish her fiction.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Grete Meisel-HessThe New Woman and the Sexual Crisis, pp. 1 - 20Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2022