The General Assembly would adopt the annual United Nations budget covering all its activities, and would determine the amounts to be supplied by the taxpayers of each member Nation for that budget. These amounts would be allotted on the basis of each member Nation’s estimated proportion of the estimated gross world product in that year subject to a uniform “per capita deduction” of not less than fifty or more than ninety per cent of the estimated average per capita product of the ten member Nations having the lowest per capita national products, as determined by the Assembly. A further provision would limit the amount to be supplied by the people of any member Nation in any one year to a sum not exceeding two and one half per cent of that nation’s estimated national product.Footnote 1

This chapter addresses the question of the funding the operations of the United Nations. It reviews the early history of UN funding and the systems that emerged as a result of the constraints that the UN Charter imposed on its members, with specific reference to the responsibilities given to the General Assembly on budgetary issues under the one country–one vote system. We also review the current structure of the UN budget, as regards both sources and uses of funds, based on the most recent data available, for the year 2016. The main focus of the chapter is on various funding mechanisms that have been put forth in the course of the history of the UN and beyond. These include Grenville Clark and Louis Sohn’s proposals contained in World Peace through World Law; an examination of the advantages of the model currently used in the European Union, which itself evolved over time into a system of reliable, independent funding; a discussion of the merits of a Tobin-like tax on financial transactions as a way to fund not only UN operations but also other development needs; and a system that would allocate resources to the UN as a fixed proportion of each member’s gross national income (GNI), without the multiple exemptions and carve-outs that are in place in today’s convoluted system of revenue generation.

Early History

Article 17 of the UN Charter indicates that “the General Assembly shall consider and approve the budget of the Organization. The expenses of the Organization shall be borne by the Members as apportioned by the General Assembly.” The Charter does not provide guidance on the criteria that should be used to ensure fair burden-sharing across its members and, being mainly a statement of principles, it certainly does not comment on whether the UN should have a consolidated budget for all of its activities – as governments tend to have under the International Monetary Fund (IMF) concept of “general government” – or whether it should have several budgets for different areas of work, such as peacekeeping, general administration and so on.

Not surprisingly, what has happened is that a body of practices has evolved over time that has resulted in the emergence of a so-called regular budget which funds the UN Secretariat and its multiple activities, a peace-keeping budget, and a budget that finances the activities of its specialized agencies. These budgets are financed by assessed contributions from members. In addition, there is a separate budget that is funded by voluntary earmarked contributions from some of its wealthier members in support of particular agencies, projects and programs. Article 18 of the Charter states that budgetary issues are one of the “important questions” on which a two-thirds majority of the membership in the General Assembly will be required to make decisions. Article 19 of the Charter envisages the removal of voting rights in the General Assembly for countries which are more than two years in arrears in their contributions, though exceptions can be made when the cause of the arrears is “beyond the control of the Member.” The General Assembly determines and updates from time to time a matrix of compulsory assessments for countries, establishing the share of the assessed budget that will be paid by each member.

The General Assembly has developed various formulas to determine individual member assessments based on the principle of “capacity to pay.” A Committee on Contributions was established in 1946 that put forward a formula weighing “relative national incomes, temporary dislocations of national economies and increases in capacity to pay arising out of the war, availability of foreign exchange and relative per-capita national incomes.”Footnote 2 On the basis of this formula, the United States was assessed a share of 39.89 percent in the early years but, under American pressure and some opposition from countries such as Canada and Great Britain, a ceiling on US contributions was agreed and implemented in several stages;Footnote 3 by 1974, the US assessed share had fallen to 25 percent and to 22 percent by 2005, where it has remained since. The incorporation of Italy in 1955, Japan in 1956 and, especially, Germany in 1973 greatly facilitated the reductions in the US contribution. Over time the General Assembly opted for a system to determine country contribution shares that many regarded as unduly complicated, using estimates of gross national product (GNP)/GNI per capita, levels of external indebtedness, with discounts given to low-income countries, offset by assessing higher contributions to wealthier members, and floors and ceilings negotiated from time to time on an ad hoc basis. A minimum contribution floor of 0.04 percent of the total budget was set at the outset of the organization’s foundation, when the UN had 51 members. As low-income countries joined the United Nations in the next several decades, this floor was reduced on several occasions and it now stands at 0.001 percent and is paid by countries such as Bhutan, the Central African Republic, Eritrea, the Gambia, Dominica, Lesotho, Liberia, Sierra Leone, Togo and others.

China has recently overtaken Japan as the second-largest contributor at 12.005 percent, and Japan (8.564 percent) and Germany (6.090 percent) are the third- and fourth-largest contributors, respectively.Footnote 4 For many decades the USSR was the second-largest contributor (14.97 percent in 1964) but, with the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 and the resulting prolonged economic crisis during much of the 1990s, Russia’s assessed share fell precipitously. By the early 2000s it would have been set at 0.466 percent, including a low-income developing country discount. Finding it perhaps difficult to reconcile this low contribution rate with its great-power status in the Security Council, the Russian authorities actually asked to make a higher contribution, set at 1.1 percent by 2000. It is 2.405 percent today. The top five contributors today account for 53.23 percent of the assessed budget (higher than the 50.85 percent during the 2016–2018 budget cycle), and the top 20 for 83.33 percent, meaning that the other 173 countries account for the remaining 16.67 percent. The five veto-wielding members of the Security Council accounted for 71.09 percent of the budget in 1946, but their share has come down to 45.40 percent in the assessments to be applied in the 2019–2021 term. The General Assembly has operated on the basis of the one country–one vote principle since its inception, which, understandably, has created tensions from time to time given its authority over budgetary matters. Switzerland’s contribution (1.151 percent) exceeds the cumulative contributions of the 120 countries with the smallest assessed shares, a list that begins with the Dominican Republic, Lebanon, Bulgaria, Bahrain, Cyprus, Estonia, Panama, all the way down to Tuvalu and Vanuatu.

Political Tensions from the One Country–One Vote Rule

Since the Charter established a two-thirds General Assembly majority threshold to approve matters pertaining to the budget, and since the voting share of the two-thirds of the membership with the smallest assessed shares adds up to only 1.633 percent (a number only slightly higher than the contribution of Turkey), this created a situation where, de facto, on budgetary matters, the “tail” was often indeed “wagging the dog,” in a big way. The imbalance stemming from the one country–one vote principle – which could have been easily anticipated in 1945 – has led to occasional calls from some of the larger contributors to introduce a system of weighted voting in the General Assembly on budgetary matters. As such proposals have not received the support of the smaller members constituting a solid majority in the Assembly, it has instead contributed to enhancing the de facto leverage of countries such as the United States, its largest contributor. It is outside the scope of this chapter to discuss the difficult relationship the United States has had with the United Nations on budgetary matters over the decades. Jeffrey Laurenti provides an excellent overview in his contribution to the Oxford Handbook on the United Nations.Footnote 5 US contributions have often been in arrears and fallen captive to internal domestic politics, and have resulted in the imposition of multiple demands and conditions over the years that have included, for instance, the introduction of a nominal zero-growth budget over a period of several years – which did much to undermine the effectiveness of various UN programs and initiatives – staff reductions, and the extraction of promises from the United Nations that it would not create a “UN standing army” nor debate, discuss or consider “international taxes.” Since 1987, at the urging of the United States, the budget has been approved “by consensus.”Footnote 6

Budgetary Management

Unpaid contributions have greatly complicated budgetary management at the UN. Countries have built up arrears to the budget in some cases because they do not regard obligations to the UN as legally binding or, in any case, to exceed in importance whatever other claims there may be on their budgets at home, or because, as in the case of the United States and the Soviet Union, they were unhappy with particular policies or practices and wanted to use their contributions as leverage to prompt change. To take an example, in the 1960s the Soviet Union accumulated more than two years of arrears because of dissatisfaction with peacekeeping operations in the Congo. Faced with the possibility of the application of Article 19 and the removal of voting rights, the Soviet authorities threatened to pull out of the United Nations. Such threats were considered credible given that the Soviet Union had already pulled out from membership at the World Bank and the IMF, organizations they would rejoin in 1992 as 15 separate republics, with Russia inheriting the veto in the Security Council. These threats resulted in a compromise that led to the delinking of the peacekeeping budget from the regular budget. One, possibly unintended, effect of this was that, in time, countries tended to see their contributions to the regular budget as being of higher priority than those to peacekeeping operations, which then resulted in the accumulation of large arrears in assessed contributions for peacekeeping; by 2007 more than 85 percent of the latter budget was in arrears.

In the early years, peacekeeping operations were small and funded from the United Nations regular budget. After the Suez Canal crisis in 1956, peacekeeping was funded from a separate budget on the basis of assessed contributions, but under a system than that applied to the regular budget. This reflected in part the very nature of peacekeeping, with needs often arising in an unpredictable fashion, but also the fact that low-income countries often felt that the cost of such operations should be largely borne by the wealthier members. Thus, in 1973, against the background of two Arab–Israeli wars and growing demands for peacekeeping operations, a system was put in place that created several categories of countries depending on the level of income per capita. Category D countries, all low-income and located mainly in sub-Saharan Africa, were granted a 90 percent discount with respect to their assessed contribution rates for the regular budget. Therefore, a country with an assessed rate of 0.015 percent for the regular budget would be expected to pay an additional 0.0015 percent to the peacekeeping budget. Other developing countries were classified as Category C and given an 80 percent discount. Thus, a country with an assessed rate of 0.75 percent would be assessed for an additional 0.15 percent as their contribution to peacekeeping. Category B countries, made up of high-income countries not members of the Security Council, would be expected to pay the same rate as applied to the regular budget (i.e., zero discount), and Category A countries consisting of the P-5 were expected to make up the shortfall.

Although this system was initially adopted on an interim basis for a one-year period, in practice it was renewed annually and remained in place until 2000, when a new compromise was arrived at that increased the number of country groupings to six and sharply reduced the discount applying to Category C countries, from 80 percent to 7.5 percent. In any case, in either system the burden of peacekeeping fell disproportionally on the United States, the United Kingdom and France, given the low assessed contributions of Russia and China which, in the latter case, by 1995 was 0.720 percent. This compromise notwithstanding, the United States imposed, unilaterally, a ceiling of 25 percent on its assessed contribution for peacekeeping. Laurenti sums up convincingly the UN’s main problem in this area: “The refusal by the largest member states to pay assessed contributions whose level or purpose displeases them has become a recurrent feature of funding politics at the UN. The consequent fragility of its financial base is one of the UN’s fundamental weaknesses.”Footnote 7

| US$ millions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agency | Assessed contribution | Voluntary untied | Voluntary earmarked | Other fees | Total 2016 |

| UN Secretariat | 2,549 | 0 | 2,063 | 535 | 5,147 |

| UN Peacekeeping | 8,282 | 0 | 392 | 52 | 8,726 |

| Specialized agencies | 3,142 | 5,060 | 24,230 | 3,028 | 35,463 |

| Of which: | |||||

| FAO | 487 | 0 | 770 | 39 | 1,296 |

| WHO | 468 | 113 | 1,726 | 57 | 2,364 |

| IAEA | 371 | 0 | 252 | 9 | 632 |

| UNICEF | 0 | 1,186 | 3,571 | 126 | 4,884 |

| Total | 13,973 | 5,060 | 26,685 | 3,615 | 49,336 |

| Organization | 1975 | 1980 | 1985 | 1990 | 1995 | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | 2016 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UN Secretariat | 268 | 510 | 618 | 888 | 1,135 | 1,089 | 1,828 | 2,167 | 2,771 | 2,549 |

| Specialized agencies | 401 | 816 | 1,071 | 1,411 | 1,871 | 2,048 | 2,446 | 3,207 | 3,247 | 3,142 |

| Of which: | ||||||||||

| FAO | 54 | 139 | 211 | 278 | 311 | 322 | 377 | 507 | 497 | 487 |

| WHO | 119 | 214 | 260 | 307 | 408 | 421 | 429 | 473 | 467 | 468 |

| IAEA | 32 | 81 | 95 | 155 | 203 | 217 | 278 | 392 | 377 | 371 |

| UNESCO | 89 | 152 | 187 | 182 | 224 | 272 | 305 | 377 | 341 | 323 |

| Total | 669 | 1,326 | 1,689 | 2,299 | 3,006 | 3,137 | 4,274 | 5,374 | 6,018 | 5,691 |

| Agency | 2005 | 2010 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UN Secretariat | 848 | 1,361 | 1,440 | 2,321 | 2,094 | 2,063 |

| Specialized agencies | 14,325 | 18,906 | 22,255 | 23,957 | 23,112 | 24,230 |

| Of which: | ||||||

| WFP | 2,963 | 3,845 | 4,095 | 4,943 | 4,469 | 5,108 |

| UNDP | 3,609 | 4,311 | 3,897 | 3,809 | 3,726 | 4,122 |

| WHO | 1,117 | 1,442 | 1,929 | 1,970 | 1,857 | 1,726 |

| UNICEF | 1,921 | 2,718 | 3,588 | 3,843 | 3,836 | 3,571 |

| Total | 15,196 | 20,300 | 23,725 | 26,423 | 25,401 | 26,685 |

| Agency | 2005 | 2010 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UN Secretariat | 2,659 | 3,953 | 4,310 | 5,145 | 5,613 | 5,713 |

| UN Peacekeepinga | 5,148 | 7,616 | 7,273 | 7,863 | 8,759 | 8,876 |

| Specialized agencies | 18,340 | 28,866 | 30,863 | 33,360 | 33,688 | 34,176 |

| Of which: | ||||||

| FAO | 771 | 1,415 | 1,380 | 1,246 | 1,219 | 1,202 |

| IAEA | 443 | 585 | 606 | 581 | 570 | 550 |

| UNICEF | 2,191 | 3,631 | 4,082 | 4,540 | 5,077 | 5,427 |

| WHO | 1,541 | 2,078 | 2,261 | 2,317 | 2,738 | 2,471 |

| Total expenditures | 20,999 | 40,435 | 42,446 | 46,368 | 48,060 | 48,765 |

a Figure for 2005 is not available; figure shown corresponds to 2007

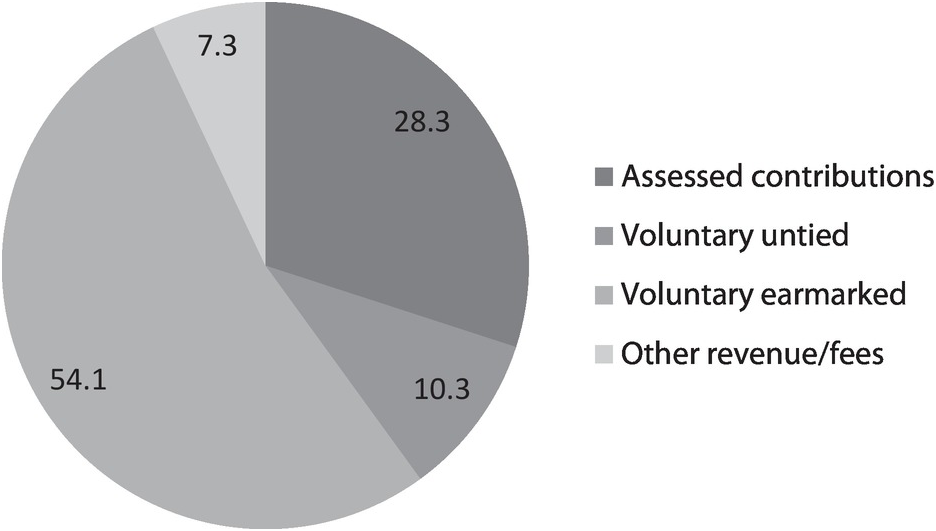

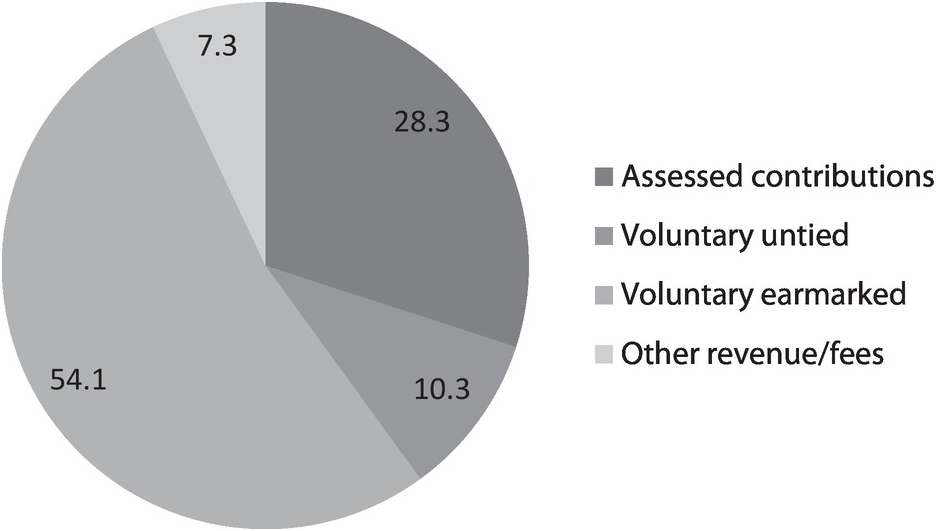

Figure 12.1. Total revenue of UN system by financing instrument, 2016.

It is useful to look at the level and the structure of funding of the UN in 2016, the latest year for which a fairly complete data set is available. We will also comment briefly on the evolution over time of some of the main revenue sources. There are several features worth highlighting.

Assessed contributions to the UN budget in 2016 amounted to US$13,973 million, of which US$8,282 million was for peacekeeping (59.3 percent of the total), with US$2,549 million allocated to the UN Secretariat’s so-called regular budget and US$3,142 million to the specialized agencies. The share of the peacekeeping budget in 1971 was a mere 6.1 percent of the total and had risen to 17.4 percent by 1991. There is some irony in the fact that the amounts allocated to peacekeeping operations rose most rapidly after 1991, with the end of the Cold War, a period that was expected to deliver the so-called peace dividend. It is noteworthy that even at US$8.3 billion in 2016, the peacekeeping budget amounts to about 0.5 percent of total world military spending.

A total of US$5,691 million was allocated to the UN Secretariat and its 20 specialized agencies. The four largest recipients among these were the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the World Health Organization (WHO), the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and UNESCO. By 1971 the regular budget accounted for about 40 percent of the assessed budget. This share had fallen to 18.2 percent by 2016.

The share of the regular budget in the total budget (including voluntary earmarked contributions) has been on a downward trend, reaching 10.4 percent by 2016.

The share of the assessed budget going to specialized agencies such as WHO, FAO and others fell from 54 percent in 1971 to 22.5 percent by 2016.

The regular budget has remained small, growing from a very tiny base at the outset of the creation of the UN when the annual budget was less than US$20 million, at an average annual rate of about 2 percent in real terms. On a per capita basis, the regular budget is equivalent to about US$0.38 per year for every person on the planet.

Of the US$26,685 million in voluntary earmarked contributions made by donors in 2016, US$24,230 was allocated to specialized agencies, with the rest going mainly to the UN Secretariat, with some small amounts allocated to peacekeeping. The largest recipients of earmarked contributions were the World Food Programme (WFP), the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), WHO and UNICEF.

Table 12.5 shows data on per capita assessed contributions corresponding to the 2015 budget, which recorded US$14,519 million in revenues. The 15 largest contributors to the UN budget on a per capita basis are Monaco, Liechtenstein, Norway, Switzerland, Luxembourg, Qatar, Denmark, Australia, Sweden, Tuvalu, San Marino, Netherlands, Finland, Austria, and Canada. The five veto-wielding members of the Security Council occupy the following positions: France (22), the United States (26), the United Kingdom (27), Russia (57), and China (93). India is in 147th place. In per capita dollar terms these contributions range from US$23–38 in the case of Monaco, Liechtenstein, and Norway, to US$0.08 in the case of India, to about US$0.01 (one cent or less) in the case of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Somalia and Bangladesh, the three lowest contributors. The United States’ per capita contribution is US$9.88, while its national per capita defense expenditure for the 2018 fiscal year was US$2,050. That is, defense expenditures are 207 times larger than UN contributions on a per capita basis.Footnote 8

The EU, which has a GDP that is broadly comparable to that of the United States, contributes 29.3 percent of the assessed budget, compared with 22.0 percent for the United States.

Table 12.5. Per capita contribution of top 15 countries to UN budgeta

| Country | Per capita contribution to UN budget, in USD | Rank |

|---|---|---|

| Monaco | 37.71 | 1 |

| Liechtenstein | 26.98 | 2 |

| Norway | 23.47 | 3 |

| Switzerland | 19.88 | 4 |

| Luxembourg | 16.13 | 5 |

| Qatar | 14.92 | 6 |

| Denmark | 14.86 | 7 |

| Australia | 13.91 | 8 |

| Sweden | 13.89 | 9 |

| Tuvalu | 13.20 | 10 |

| San Marino | 13.07 | 11 |

| Netherlands | 12.63 | 12 |

| Finland | 12.07 | 13 |

| Austria | 11.96 | 14 |

| Canada | 11.71 | 15 |

| France | 10.92 | 22 |

| United States | 9.88 | 26 |

| United Kingdom | 9.87 | 27 |

| Russian Federation | 3.13 | 57 |

| China | 0.83 | 93 |

| India | 0.08 | 147 |

a For assessed contributions (i.e., excluding voluntary contributions) but also includes all permanent members of Security Council and India

Figure 12.2. Total voluntary contributions of top ten countries, US$m, 2015.

Perhaps the most interesting feature of the data is the extent to which, by 2015, total voluntary contributions dwarfed contributions to the regular budget, by a factor of nearly 11, and even exceeded by a significant margin total amounts budgeted to specialized agencies, peacekeeping and the regular budget combined. Voluntary earmarked contributions tend to be lopsided, with four countries – the United States, the United Kingdom, Japan and Germany – accounting for about 42 percent of the total and the European Union accounting for about a third. The General Assembly, which discusses, recommends and approves the assessed part of the budget, has little say on the uses of voluntary contributions, which tend to reflect individual donor country economic, political and developmental priorities. Donor countries have bypassed the General Assembly and use the United Nations infrastructure as a conduit to leverage the impact of their bilateral aid programs. In this way, they may use the UN label, while maintaining for themselves full discretion over how to spend these contributions. Some critics of voluntary funding, including Haji Iqbal,Footnote 9 point out that the UN Charter makes no provisions for such funding; it assumes that all UN expenditures will be based on assessed contributions paid by members and the General Assembly will retain authority over the levels and associated priorities of such funding. Indeed, from this perspective, voluntary contributions can be seen as having a wobbly legal foundation. One could argue that a rigid interpretation of the UN Charter on this point and, in particular, the application of the one country–one vote principle and the lopsided distribution of contributions across members would have long ago starved the UN budget of needed funds.

Faced with the option of boosting contributions to the regular budget in order to match growing needs within a rapidly interdependent community of nations grappling with an expanding list of global challenges, but having little say on the use of such resources within the General Assembly, donor countries opened up a new avenue of funding over which they would have the control that they lacked within the regular budget. Thus, voluntary contributions were a natural response to the fiction that we live in a world in which Dominica, with its 0.001 percent contribution, should have an equal say over the disposition of resources as Japan, with a contribution 8,564 times larger. Nevertheless, one perhaps unintended consequence of the large volume of voluntary contributions with respect to assessed funding is that the majority of United Nations staff do not, in fact, ultimately work for the organization that pays their salaries. Rather, they work for the donor countries that provide the funding for the many programs to which these funds are earmarked. Likewise, while many people may think that the organization is run with a US$49 billion annual budget, the reality is much more modest; assessed contributions to the UN Secretariat budget in 2016 amounted to slightly more than US$2.5 billion.

Proposals for United Nations Funding

This situation has led many to argue that a strengthened UN system, with a broader set of responsibilities and strengthened and expanded institutions would need a reliable source of funding, free of the inconsistencies, opaque practices, arbitrariness and contradictions that have emerged through several decades of practice. It would also need to be delinked entirely from the kinds of domestic political considerations that have sometimes intruded upon budget debates and have held the UN’s activities hostage to the demagoguery or bias of local politicians, the occasional emergence of isolationist tendencies in some member countries and so on. In light of the need for new, coherent solutions to funding a UN adequate for twenty-first century challenges we will put forth four proposals and examine their respective merits and potential problems. We feel strongly that any one of them would be superior to the current non-system.

A Fixed Proportion of GNI

Under this proposal based on work by Schwartzberg,Footnote 10 the United Nations would simply assess member contributions at a fixed percent of their respective GNIs. Total world GNI at market prices in 2017 was US$79.8 trillion. A 0.1 percent of GNI contribution to the UN budget would generate US$79.8 billion, a sizable sum to start with. The main advantage of this system is simplicity and transparency. Every country would be assessed at the same rate; the criterion for burden-sharing is crystal clear. Contributions are linked to economic size – as in the current system – but without the need for carve-outs, exceptions, floors and ceilings, discounts and the need to develop “formulas” of questionable integrity and credibility. There is also no need to develop a separate UN tax collection machinery, which has been noted as a potential problem in other proposals put forward in the past to address the problem of UN funding. One potential criticism of this proposal is that the tax rate is not progressive; the same rate applies to all countries, regardless of the level of income. We feel that this feature is not a problem in the same way that flat taxes on personal income can sometimes be. First, there is nothing to prevent the UN from ensuring that most of the benefits of its activities and expenditures are, in any case, allocated to its lower-income members. This is, of course, already happening in the current system, particularly in the case of the spending channeled through its specialized agencies and programs. Therefore, the absence of progressivity in the tax rate assessed on contributions is more than offset by the presence of a large measure of progressivity in the allocation of benefits to lower-income countries.

Second, even at 0.1 percent of GNI the assessed tax rate is low. Countries typically spend an average of 2 percent of GNI on their militaries – 20 times more than their proposed contributions to the UN budget. To the extent that, at 0.1 percent of GNI, the UN would be empowered to do a great deal more in terms of the delivery of enhanced security to its members (see Chapter 8, as strengthening the rule of law and the other measures enhance the members’ security significantly), this new system could make great economic sense, in terms of the benefits it would deliver. At present, there are a large number of countries for which their assessed contributions amount to less than five cents per person per year, amounts that are strikingly low and that have likely contributed to a culture of lack of ownership of the United Nations by many of its members. Furthermore, it would have another important advantage. Instead of empowering segments of public opinion – for instance in the United States, which have generally made much of the fact that their country contributes, say, 22 percent of the UN’s assessed budget – now the narrative would simply shift to observing that all countries are assessed at the same (low) rate, thus ending the argument.

In any proposal for new funding mechanisms for the UN we need to move to a more representative system of weighted voting in the General Assembly, such as already exists at the World Bank and the IMF. It is not reasonable to expect the United States, China, Japan and Germany, the four largest contributors, accounting for 28 percent of the world’s population, to account for 2 percent of votes in the General Assembly (e.g., as four out of 193 members). This imbalance has been a primary factor explaining the emergence of the distortions and inefficient practices and all-around chaos that today characterize UN finances. With the reformed model, at just 0.1 percent of GNI, contributions today would exceed the UN budget, generating resources that could, for example, be put in an escrow account “to enable the United Nations to respond expeditiously to unanticipated peacekeeping emergencies and major natural disasters.”Footnote 11 Better yet, such excess resources could be invested, as Norway has done so successfully with its Petroleum Stabilization Fund. Moreover, since climate change shocks are expected to affect all members, one can imagine situations in the future where all members may have the right to draw on such resources in an emergency, as is the case, for instance, with many of the IMF’s funding facilities. In the 1970s, even the United Kingdom and Italy gained access to the Fund’s standby arrangements.

Furthermore, with a system of weighted voting in the General Assembly – meaning a more sensible system of incentives for members – one can imagine a gradual return to the vision that was originally laid out in the UN Charter, one in which expenditures would truly be subject to General Assembly oversight and scrutiny and voluntary contributions would not play the disproportionately large role that they play today. A final advantage of this system is that it would reposition the United Nations and, in particular, the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC), to play a more vital role in questions of economic and social development, as envisaged in the Charter.Footnote 12 The existing funding arrangements have done much to sideline the United Nations from vital debates that have taken place in recent decades, for instance, in terms of the response to the global financial crisis in 2008, with other groupings – the G-20 – playing a more prominent role but, obviously, facing legitimacy issues of its own because of the absence of voice for the other 173 members. We will call this the Schwartzberg proposal, in honor of its chief proponent.

The Clark–Sohn Proposal

In World Peace through World Law, Clark and Sohn put forward a proposal of their own that merits examination. Because they envisage a considerably strengthened United Nations and anticipate a General Assembly operating under a system of weighted voting, they propose revisions to Article 17 which, for instance, “would greatly broaden the control of the General Assembly over the activities of all the specialized agencies, not only by requiring that the separate budgets of these agencies be approved by the Assembly, but also by making the general budget of the United Nations the main source of their funds.”Footnote 13 Clark and Sohn’s proposal assumes that each nation would contribute a fixed percentage of its GNP to the United Nations and does not specify what the domestic sources for those revenues would be. These contributions are an obligation of membership and there would be no need for the United Nations to develop a tax collection machinery, beyond that already existing in member countries. They do, however, have very detailed proposals on the distribution of the burden across members, given a particular budget. It is an interesting exercise to see how the burden would change in their proposals, with respect to the assessments in force for the period 2016–2018. We will do this by describing their proposal first and then by updating their calculations using population and GDP figures for 2016.

For each nation’s GNP, Clark and Sohn propose making a so-called per capita deduction that “would be equal to an amount arrived at by multiplying the estimated population of such nation by a sum fixed from time to time by the General Assembly, which sum shall be not less than fifty or more than ninety percent of the estimated average per capita product of the people of the ten member Nations having the lowest per capita national product.”Footnote 14 The resulting amount would be the “adjusted national product” and the calculated shares of the budget attributed to each nation would be determined by the ratio between this concept and the sum of all “adjusted national products” for all member nations. They provide a useful illustration using notional GNP and population figures for two countries in 1980 (see pp. 351–352 in World Peace through World Law). We have done these calculations for just over a dozen countries, and Table 12.6 compares the assessments in use by the United Nations during 2016–2018 with those that would emerge from the Clark and Sohn proposal using updated figures.Footnote 15

Table 12.6. The Clark–Sohn proposal (in percent)

| UN member | Current assessmenta | Adjusted assessment |

|---|---|---|

| Bangladesh | 0.010 | 0.248 |

| Brazil | 3.823 | 2.379 |

| China | 7.921 | 14.820 |

| France | 4.859 | 3.350 |

| Germany | 6.389 | 4.729 |

| India | 0.737 | 2.578 |

| Japan | 9.680 | 6.706 |

| Malawi | 0.002 | 0.000052 |

| Nigeria | 0.209 | 0.481 |

| Norway | 0.849 | 0.505 |

| Sweden | 0.956 | 0.695 |

| Russia | 3.088 | 1.699 |

| United Kingdom | 4.463 | 3.572 |

| United States | 22.000 | 25.362 |

| World | 100.000 | 100.000 |

| Memo items: | ||

| Average income per capita | ||

| for 10 poorest countries (US$) | 418.1 |

a Current assessments correspond to the 2016–2018 period

As can be seen, the main impact of their method is to substantially raise the assessed contribution of China, to do so marginally for the United States – both of which would now account for 40.2 percent of the budget, compared with 29.9 percent today – reduce the contributions of countries such as Japan, Germany, Norway, Sweden, and the United Kingdom, increase the contributions of countries such as India and Nigeria, and virtually eliminate the contributions of countries with the lowest income per capita. Malawi’s assessed contribution, for instance, would drop from 0.002 percent today, to 0.000052 percent in the Clark–Sohn proposal. The ratio of the contribution rate of the United States to that of Malawi would rise from 11,000 today to 487,731 under their proposal.

We understand the motivation of Clark and Sohn in introducing something like a “low-income discount” for assessed contributions to the United Nations budget. They made these proposals in the late 1950s, when the incidence of extreme poverty was much higher than it is today and when living conditions, more generally, were appalling in much of the developing world. Average life expectancy in 1960 was 52 years, compared with 72 today, and infant mortality was, likewise, extremely high by today’s standards. Indeed, the current financing system already has some of this flavor, with low-income countries contributing considerably less than their indicative GNI share and high-income countries contributing correspondingly more. We favor a system that would impose a more equitable burden across the United Nations membership. There is much to be gained from developing countries seeing that they have a stake in a reformed United Nations and that they are contributing a fair share to an organization that, in any event, will, at least as regards its priorities in the area of economic and social development, be very focused on low-income countries, from support for fragile or post-conflict states, assistance in conflict prevention, various other types of national capacity-building and, more generally, dealing with the challenges of still very high levels of extreme poverty, illiteracy and malnutrition.

The EU Model

Another option is to introduce a funding mechanism similar to that currently operating in the EU, where each country’s payment is divided into three parts: a fixed percentage of GNI, customs duties collected on behalf of the EU (known as “traditional own resources”) and a percentage of VAT income, all of which member states collect and allocate automatically to the EU budget. The EU has not developed a separate revenue collection machinery, with the collection of taxes left as a responsibility of individual states. This system has served the EU extremely well. It has provided a reliable source of funding that is independent of domestic political considerations. Member countries do not get to withhold contributions whenever they disagree with the orientation of particular policies (on which, in any case, they get to vote under a system of proportional voting), or when other domestic priorities emerge. The system provides a level of automaticity in funding that has eliminated discretion at the level of individual member states.

Consequently, the EU is able to frame budgets in a medium-term perspective – it approves a budget at six-year intervals – and can plan accordingly. As regards the tax base, for those countries without VAT (a minority of states), one possibility would be to allocate a share of indirect taxes on goods and services collected in each member country. The percentage of such taxes to be allocated to the UN budget could be pitched to achieve the desired end in terms of the volume of total contributions. For those few countries without well-developed systems of indirect taxation, one could use an alternative tax base, such as a share of taxes on corporate profits, assessed at levels that would achieve proportional burden-sharing across countries. One advantage of this proposal is its automaticity. Having agreed to pass on to the United Nations a share of VAT or indirect taxes, funding would not be subject to members’ whims and discretion. As long as the United Nations was discharging its responsibilities as called for in the Charter and under the general supervision and oversight of the General Assembly, funding would flow regularly, empowering the organization to frame its activities in a medium-term framework, free of the uncertainties and vagaries of the current system.

A Tobin-like Tax

Another possibility is the tax proposed by James Tobin on spot currency transactions or its successor, a tax on financial transactions. Tobin made his initial proposals in the immediate aftermath of the collapse of the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates in 1971, and its primary motivation was less to generate tax revenue and more to dampen the speculation that was contributing to heightened exchange rate volatility in foreign exchange markets, delinked from broader economic fundamentals, and placing a particularly heavy burden on producers and consumers of traded goods. Tobin’s proposals have generated considerable debate, controversy and confusion over the years. It is worthwhile, therefore, to briefly summarize his thinking, particularly as it evolved over the 25 years following his Janeway Lectures at Princeton University in 1972 when the proposal was first made. By the mid-1990s, and against the background of multiple financial crises in various parts of the world, Tobin expressed particular concern about speculative attacks against countries that were undergoing some financial turmoil and were forced to increase interest rates sharply to defend their currencies, with deleterious effects on economic activity and employment.

Since he was skeptical that the world would quickly move to the full coordination of monetary and fiscal policies and the introduction of a common currency, he opted for throwing “some sand in the well-greased wheels” of international money markets.Footnote 16 Tobin lamented the exchange rate volatility that had emerged in the wake of the collapse of the fixed exchange rate regime in the early 1970s and noted that “in these markets, as in other markets for financial instruments, speculation on future prices is the dominating preoccupation of the participants … In the absence of any consensus on fundamentals, the markets are dominated—like those for gold, rare paintings, and—yes, often equities—by traders in the game of guessing what other traders are going to think.”Footnote 17 While he recognized that financial markets often imposed a degree of discipline on countries’ monetary and fiscal policies, he thought that the punishment delivered by speculation often far exceeded the policy mistakes or misalignments brought about by the authorities, as had been the case in Mexico in 1994, and as would become clear during the 1997 Asian financial crises and other emerging market crises precipitated in its wake.

Tobin’s essential point was to “penalize short-horizon round trips” in foreign currency transactions while not affecting in any significant way the incentives for trade in commodities and longer-term capital investments. He thought that a tax administered with some flexibility would be a better instrument to combat runaway speculation than bureaucratic controls and/or burdensome financial regulations. In his 1996 contribution to The Tobin Tax – Coping with Financial Volatility, he observed that 80 percent of foreign exchange transactions involved round trips of seven days or less, with the majority of these being of one-day duration.Footnote 18 By 1995, daily foreign exchange trading amounted to US$1.3 trillion, or US$312 trillion on an annual basis, dwarfing trade in equities and nearly 67 times larger than the total value of annual world exports.

Tobin commented that part of the opposition to the tax proposal was philosophical: it was “rejected on the same general grounds that incline economists to dismiss out of hand any interferences with market competition, including, of course, tariffs and other barriers to international trade in goods and services.”Footnote 19 The belief that expectations of economic actors are rational and that financial markets are efficient and that ultimately “financial markets know best” is widespread among market participants, even though, Tobin argued, it was not clear to him that trade in financial assets and trade in goods and services were one and the same thing, subject to the same insights from economic theory that had long been in favor of free trade. By the time of the global financial crisis in 2008, James Tobin was no longer with us, but one can safely assume that he may have agreed with another Nobel laureate, Robert Shiller, and his statement that our “economies, left to their own devices, without the balancing of governments, are essentially unstable.”Footnote 20 Such a tax, it was also argued, would also damage liquidity in currency markets, drive these markets to tax-free havens if it were not a universal tax, and so on.

John Maynard Keynes had already advocated a general financial transaction tax in 1936 to discourage the emergence of a class of speculators whose activities would be primarily motivated by the search for short-term profit linked to asset price changes and which, in his view, would needlessly add to market volatility. Keynes had warned that “it makes a vast difference to an investment market whether or not they (meaning serious investors who purchase investments on best long-term expectations of value) predominate in their influence over the game-players.”Footnote 21 Tobin returned to and elaborated on his original proposal in 1978 in his presidential address to the Eastern Economic Association. He said:

It would be an internationally agreed uniform tax, administered by each government over its own jurisdiction. Britain, for example, would be responsible for taxing all inter-currency transactions in Eurocurrency banks and brokers located in London, even when sterling was not involved. The tax would apply to all purchases of financial instruments denominated in another currency—from currency and coin to equity securities. It would have to apply, I think, to all payments in one currency for goods, services, and real assets sold by a resident of another currency area. I don’t intend to add even a small barrier to trade. But I see offhand no other way to prevent financial transactions disguised as trade … Doubtless there would be difficulties of administration and enforcement. Doubtless there would be ingenious patterns of evasion. But since these will not be costless either, the main purpose of the plan will not be lost.Footnote 22

Supporters of the so-called Tobin tax have noted that with more than US$5 trillion traded daily on the currency markets by 2016, a 0.05 percent tax could generate some US$2.5 billion per day in revenue (about US$600 billion on an annual basis), which could then be directed to multiple ends, from climate change mitigation and adaptation to worthy projects aimed at poverty alleviation, inclusive economic growth, global public goods and so on. Indeed, one could make the argument that the case for the tax has become stronger in the wake of the 2008–2009 global financial crisis. As a result of the multiple government interventions to mitigate the impact of the crisis, levels of public indebtedness in rich countries – the providers of the bulk of development aid – are sky high, higher, in fact, than at any time since the end of World War II, and this has sharply curtailed their appetite for substantially boosting development aid. Tobin, using the figures for trade volumes in foreign exchange for 1995 (US$1.3 trillion per day), thought that the revenue collected would be less because the introduction of the tax would dampen the volumes traded, particularly for trades with a very short horizon for which even a small tax, on an annualized basis, applied to multiple transactions would raise transaction costs significantly. He also noted that the lion’s share of trading in the foreign exchange market took place among financial intermediaries, and were not customer–bank transactions, as were those supporting international trade in goods, for instance, or linked in some fashion to some real economic activity.

The Tobin tax proposals have generated a lively debate in policy-making circles and the academic community. Some have argued that a tax levied on currency transactions could, through creative financial engineering, be evaded. Moreover, not all foreign exchange purchases have a speculative dimension. There is a difference, it is argued, between hedging and speculation. Hedging is intended to protect the investor against unpredictable price changes; it is a way to limit price risk and can be seen as a form of insurance. Speculation, on the other hand, has the investor assuming greater risk in the expectation of a higher profit linked to price volatility and is, thus, no different than gambling. To avoid being fooled by the emergence of financial instruments that would disguise a foreign currency transaction (on which a tax would be due) in a different product (to which the tax would not apply), it might be better to shift the original Tobin tax idea, some argue, to a generalized transaction tax that would be broad enough to capture a wide spectrum of financial instruments.

In other words, one would wish to create a tax that would sharply limit the incentives for substitution across financial instruments or jurisdictions. Such a tax would have added benefits with respect to the original Tobin proposals. It could, in principle, generate more revenue, it would not disadvantage one type of financial transaction (i.e., foreign exchange trading) vis-à-vis others, and by discouraging speculation, it might actually steer financial resources to other more productive, value-creating ends, with a higher social return. Obviously, the level of the tax would be important. There is ample evidence from tax regimes across the developed and developing world that tax rates that are too high can unleash all sorts of perverse incentives (e.g., growth in the informal economy, tax evasion) that ultimately have totally counterproductive effects. On the one hand, according to the World Bank, countries in sub-Saharan Africa have the highest total tax rates in the world and also the narrowest tax bases and lowest levels of revenue collection.Footnote 23 On the other hand, the United Kingdom assesses a Stamp Duty on transactions on shares and securities without, it would appear, having hindered the growth of a robust financial sector. The Netherlands, France, Japan, Korea and other countries have introduced similar taxes as well.

There is also an interesting debate on the issue of how the tax would be collected. Here, the debate has evolved over the past several decades because of advances in technology and the concentration of financial transactions in a relatively small number of markets. Brazil introduced in 1993 a tax on bank transactions to widespread skepticism that the tax would actually work from a tax administration point of view, with many arguing that evasion would sabotage the effectiveness of the tax. However, digital technologies empowered the tax authorities and the tax proved to be fairly evasion-proof. Indeed, more generally, the arrival of online tax payments has reached even low-income countries by now and authorities are far more adept today at plugging revenue leakages that, in the past, were also associated with a high incidence of corruption. London, New York and Tokyo account for close to 60 percent of all foreign exchange trading; seven financial centers account for more than 80 percent of all transactions and, increasingly, transactions are cleared and settled in a centralized fashion, greatly facilitating tax collection. Tobin thought that the problem of tax evasion – which applies to all taxes and is hardly ever used as an excuse not to assess a particular tax – could be addressed in a number of ways. First, he thought that the tax could be collected by the countries themselves, and that developing countries in particular could be allowed to keep a significant share of the amounts collected to fund national development needs.

Second, tapping into a new revenue stream, countries could opt to lower other taxes, to reduce deficits, to ensure a more sustainable debt-servicing profile or to redress the effects of revenue losses linked to the globalized nature of the economy, with production and plant capacity much more mobile than had been the case at the turn of the twentieth century. This could create positive incentives for countries to voluntarily agree to the introduction of the tax. Given the international nature of the tax, he thought that the IMF’s Articles of Agreement could be amended to make the introduction of the tax an obligation of Fund membership.Footnote 24 This would imply that IMF members would not have access to its various financing windows and other benefits if they opted not to introduce the tax. Since a large share of foreign exchange transactions are concentrated in a relatively small number of markets, some general agreement among a handful of financial centers would most likely suffice to capture a large share of the revenue.

A clearly important issue pertains to the impact of a financial transactions tax on the economy. Would it reduce employment, not just in the financial sector but in other sectors of the economy that play a supporting role to finance, and by how much? Would it reduce liquidity in the markets? Would it lead to cross-border arbitrage as other jurisdictions (i.e., tax havens) sought advantage from the absence of the tax, if serious efforts are not made to ensure it is a universal tax? Critics of the tax point to the experience of Sweden, which in the 1980s introduced a tax on the trading of equities and, several years later, on fixed income securities. Because a significant share of trading in the Swedish market moved to London and New York, tax revenues were smaller than anticipated and the authorities ultimately opted for reducing the taxes and finally eliminating them altogether.

Other countries, however, have had much better experiences, including Japan, Korea and Switzerland, where a variety of taxes have been in place for many years and have not prevented the emergence of strong, deep financial sectors. Obviously, consideration of the tax would require the balancing of several objectives, from the desirability of generating additional revenue to promote economic development objectives (and addressing intensifying global catastrophic risks) to ensuring that implementation of the tax is feasible, and that it involves appropriate levels of international coordination and cooperation to ensure its success. In any case, given the size of today’s United Nations budget and the potential revenue to be collected through a Tobin tax, we think there is merit in Tobin’s idea that countries could be presented with a menu of choices as to how to allocate the proceeds of the tax, including, of course, a substantial allocation to the United Nations.

Indeed, in the longer term a Tobin tax or something similar, taking advantage of the substantial opportunities generated by economic globalization for government revenue generation, could be a promising avenue to provide funding to the United Nations, over and above the levels contributed from national treasuries linked to a fixed percentage of GNI. However, political opposition could be strong, given powerful anti-tax sentiments in many countries such as the United States, where even a carbon tax remains a distant prospect.Footnote 25 Financial sector interests in many countries are powerful and it is not difficult to imagine armies of lobbyists pressuring (or intimidating) lawmakers not to support the tax. Eichengreen makes the important observation that one would have to address in some way the issue of the mismatch between the volume of the tax that would be collected in particular jurisdictions and the ability or willingness of those countries to provide the concomitant levels of aid linked to the tax.Footnote 26 London accounts for a large share of foreign exchange transactions worldwide but the United Kingdom, though a generous donor, accounts for a much smaller share of total donor funding to the United Nations and other development initiatives. The point is a valid one, but it simply highlights that one would have to implement the tax in the context of international agreements that addressed the issue of burden-sharing through the balancing of multiple national and global objectives.

Schwartzberg has a different set of arguments against the introduction of a Tobin tax to fund the United Nations, some of which are relevant and cannot be ignored. One obvious consideration is that under existing chaotic financing arrangements, the United Nations does not have (for now, anyway; this could change, obviously) the capacity to spend in an efficient, value-creating way the large sums of money that could be collected through a Tobin-tax type of instrument. This is currently true, but it is not an argument against the tax itself; it is rather a commentary on the state of the United Nations, and the “benign neglect” it has suffered. He is also concerned that in the foreseeable future the United Nations will not have the administrative capacity to collect such a tax. This, in our view, is not a persuasive argument because, as already argued, there would be no need for the United Nations itself to be involved in the collection of such a tax through the creation of some UN fiscal agency. The tax would be collected – as suggested by Tobin – by the tax authorities in the countries where the transactions would take place and simply passed on to the United Nations or other recipients, as EU members do with the share of VAT contributions and customs duties that go to the European Commission in Brussels.

UN Budget Independence?

Far more persuasive is the argument Schwartzberg puts forward that the world is perhaps not yet ready to give the United Nations the kind of independence that having a direct revenue stream would theoretically provide. Empowering the United Nations by delinking its income from the discretion of its contributing members could feed into a narrative that argues that what is being created is a world government. The main response to this concern argues that giving the United Nations an independent source of funding could come with a shift to a system of weighted voting in the General Assembly, correcting the historic imbalance previously described. In any case, the experience of the EU in this respect is clearly relevant; giving the EU an independent source of funding has co-existed with a considerable degree of latitude for member states to exercise sovereignty in those areas not directly the responsibility of EU institutions.

Second, as described, the members of the United Nations themselves would determine what share of the global Tobin-like tax is allocated to the United Nations and what share goes to other ends, outside of the UN framework. This argument also applies to the first two funding proposals outlined previously. We have used, in the Schwartzberg proposal, a 0.1 percent of GNI contribution rate, but this rate could be agreed upon by members, in light of perceived needs and the desirability of creating a reserve for future contingencies. In principle, it could be reduced or increased, pari passu the likely need for global action in the future across a range of areas. Should, for instance, the international community finally get serious about global disarmament (as we have proposed in Chapter 9, in the context of the bringing into being of an International Peace Force), the contribution rate could be raised to finance some of the transition costs associated with the retraining and redeployment of the millions of people currently employed in the military-industrial complex.

The point here is that the ultimate authority for funding levels remains with United Nations members, but in a way that is more transparent and efficient than the current system, which has distributed power over the budget in a very uneven way and has rendered the United Nations increasingly irrelevant in a number of areas.

Third, a United Nations with a more reliable and larger income stream will be a more effective organization, at a time when budgets everywhere are going to come under pressure because of demographic trends (e.g., aging populations in much of the developed and emerging world), the costs associated with the impact of climate change and, sooner or later, the need to deal with the effects of the next global financial crisis. As the United Nations is empowered not only to come to the assistance of low-income countries, but becomes a truly global organization with something to offer to all its members, public perceptions of the organization’s usefulness could shift in a fundamental way. For example, we think that the business community could be a strong advocate for the creation of a dependable system of revenue generation for the United Nations, given the large economic costs associated with economic and political instability in many parts of the world, as indicated in Chapter 8 on the establishment of an International Peace Force or, more recently, the concerns expressed by senior policy-makers (e.g., the Governor of the Bank of England) about the potential financial shocks of climate change.

Our Preferred Option for Now

We think that in the short term, the Schwartzberg proposal of setting contribution rates at a small fixed share of each country’s GNI has multiple merits.Footnote 27 Something like 0.1 percent of GNI would not be onerous. It would create a sense of ownership of the organization across the membership, in a way that would have numerous long-term benefits for the United Nations’ relevance and credibility. It would be transparent and easy to administer and would relieve the General Assembly from constantly having to come up with novel schemes that in the end violate the principle of even-handedness of treatment across members. A move to a new funding mechanism would also have to be accompanied by a recommitment from UN members to the principle that contributions to the budget are a legal obligation of membership, not a choice that members make based on other considerations, such as whether they like or support (or not) particular programs or activities. Using budget contributions as leverage (particularly by the larger countries) to encourage reforms within the United Nations system is not consistent with the cooperative nature of the organization, where change should come as a result of deliberations and consultations among members and the forging of consensus for change.

With a system of weighted voting in the General Assembly, it could also allow a return to a budget where the United Nations itself (rather than donors) had ultimate say on the uses that are made of the resources collected, as opposed to the present system where, de facto, the General Assembly has lost control of the lion’s share of the budget to its wealthier members through the use of voluntary earmarked contributions, where national donor priorities take precedence over the interests of the whole membership.

Over the medium term the above proposals are not mutually exclusive. There is no reason why the Schwartzberg proposal could not in time be complemented by something like a Tobin tax. As the United Nations established a track record of fiscal prudence and efficiency in the management of financial resources, there is reason to believe that members might be ready at some point to entrust it with a larger body of funding, particularly if by then all the members of the UN, not just its low-income members, can have access to its various programs and facilities.

In connection with the goal of a properly resourced and enhanced UN system, a high-level panel of experts should be convened to explore additional international revenue generation mechanisms, including, for example, an international carbon tax on fossil fuel consumption, a global tax on certain types of mineral resource extraction, an internationally tradable system of pollution permits, duties on alcohol and tobacco, a global wealth tax or other workable ideas, whether based on effective existing international schemes (e.g., that of the International Maritime Organization) or otherwise. In respect of the taxation of fossil fuels, it is noteworthy that according to a 2015 IMF study, at present, on a global scale, some US$5.3 trillion is spent annually subsidizing the consumption of gasoline, coal, electricity and natural gas – a sum equivalent to 6.5 percent of world GNP. Sixty percent of the benefits of the subsidy for gasoline go to the top 20 percent of the income distribution, highlighting the deeply regressive nature of such subsidies, which have become an instrument for worsening income disparities, at a time when such inequities have reached unprecedented levels. According to the IMF, the elimination of such subsidies would result in a 20 percent drop in emissions of CO2, contributing to mitigation of the impacts of climate change.

One important element in empowering the United Nations by expanding the envelope of resources available to it and reducing the uncertainty of resource flows, which has been a central characteristic of its history, is to signal to its member countries that resources will be used responsibly and transparently, to build trust in the organization’s capacity to enhance the efficiency of resource use.Footnote 28 This would strengthen the hand of those who have long argued that contributions to the UN budget are an inseparable obligation of membership, not to be used to blackmail or coerce the organization in the interests of national prerogatives. Indeed, in tandem with such reforms, the UN should play a crucial role in helping its members address a number of serious problems that currently afflict member country tax systems, such as the “race to the bottom” that results from tax competition and that, if allowed to continue, is likely to limit further the ability of governments to respond to vital social and economic needs.Footnote 29 We also refer the reader to the discussion on the relationship between corruption and the ability of governments to collect tax revenues presented in Chapter 18, which includes a proposal for the creation of an International Anti-Corruption Court.