5 - Giants and Dwarfs in the Tyrolean Courts : Documents, Portraits, and the Kunst-und Wunderkammer at Schloss Ambras

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 13 April 2024

Summary

Abstract

In imagination and legend, the Alps have functioned as the dwelling place of giants and dwarfs. However, in the Tyrol by the late fifteenth century “real” individuals characterized as having macrosomia (gigantism) and microsomia (dwarfism) had begun to find a prominent place in the Habsburg courts. One of the most enthusiastic proponents of this princely fashion was Archduke Ferdinand II (1529–1595) who not only included giants and dwarfs in his household, but also began collecting their portraits and related paraphernalia in his Kunst- und Wunderkammer at Schloss Ambras. This essay establishes the importance of giants and dwarfs in the Tyrolean courts and their centrality to Ferdinand's collection, which duly testifies to a shared taste among the German-speaking courts.

Keywords: Archduke Ferdinand II, Archduke Sigmund, Habsburg, Innsbruck, Thome[r]le, cabinets of curiosities

Popular characters in the medieval chivalric romances, giants and dwarfs also figured in the legendary accounts which accorded them special powers in the Tyrol. The very idea that the hostile, suspicious, or treasure-guarding creatures predominantly lived out their existence in wild mountain landscapes made the Alpine region their ideal place of residence. The giant Grim or the dwarf king Laurin from the legends surrounding the hero Dietrich von Bern are vivid examples of this. In the course of their adventures, the central hero of the epic (which can be traced back to the ninth century, but certainly goes back to an earlier narrative tradition) and his companions must repeatedly fight supernatural enemies who have settled in the inaccessible and forbidding mountain world of the Alps; thus these legendary beings form the counter-world to that of the humans and to civilization. There was also the mythical giant Haymon, who is said to have lived in the ninth century, and is traditionally considered to be the founder of Wilten Premonstratensian Monastery in Innsbruck. Having killed the dragon who had destroyed the monastery several times, Haymon was later honored with a polychrome wooden statue (ca. 1460–70) erected in the church of the monastery itself. The statue shows Haymon standing on a small platform with an inscription and displaying the snake-like red dragon's tongue in his hand to assert his victory over the monastery's evil foe (figure 5.1).

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

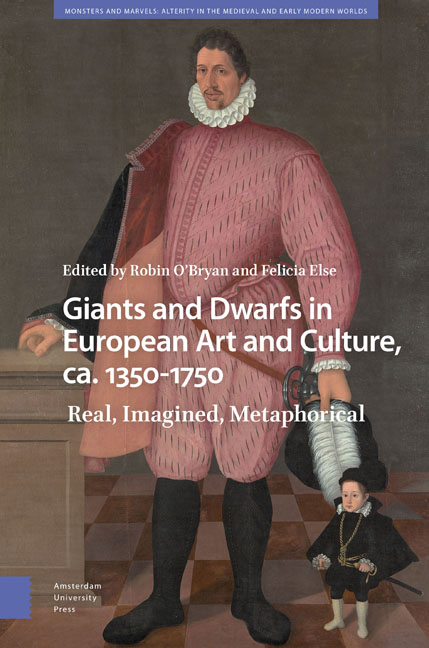

- Giants and Dwarfs in European Art and Culture, c. 1350-1750Real, Imagined, Metaphorical, pp. 183 - 210Publisher: Amsterdam University PressPrint publication year: 2024